Conversation Starters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Investment Funds

QV Equities Limited ABN 64 169 154 858 Appendix 4E – Preliminary Final Report For the year ended 30 June 2020 For personal use only QV Equities Limited Appendix 4E 30 June 2020 Preliminary Final Report This preliminary final report is for the year ended 30 June 2020. Results for announcement to the market (All comparisons to the year ended 30 June 2019). Up % $ $ movement Revenue from ordinary activities 14,935,401 811,676 6% Profit from ordinary activities before tax attributable to equity 11,899,749 1,075,543 10% holders Profit from ordinary activities after tax attributable to equity holders 10,478,231 1,090,603 12% Dividend Information Amount per Franked Tax Rate for Share Amount per Franking (Cents) Share (Cents) Interim dividend per share (paid 17 March 2020) 2.2 2.2 30% Final dividend per share (to be paid 18 September 2.2 2.2 30% 2020) Total dividends per share for the year 4.4 4.4 Final dividend dates Ex – dividend date 26 August 2020 Record date 27 August 2020 Payment date 18 September 2020 Dividend Reinvestment Plan The Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) is not operational for the final dividend of 2.2c per share due to the on- market share buy-back currently being executed by the Company. Net tangible assets 30 June 2020 30 June 2019 Net tangible asset backing (per share) before tax $0.94 $1.15 Net tangible asset backing (per share) after tax $0.98 $1.13 Audit For personal use only This report is based on the financial report which has been audited. -

A Directory of Support Services for People Affected by Cancer in the ACT

CANCER SERVICES ACT Cancer Services ACT A directory of support services for people affected by cancer in the ACT For cancer information and support call For information and support on cancer and cancer related issues call 13 11 20 Email [email protected] July 2018 13 11 20 Visit www.actcancer.org www.actcancer.org Note to reader All care is taken to ensure that the information in this booklet is accurate at the time of publication. Please note that inclusion of a service in this directory does not imply any endorsement or association of that service by Cancer Council ACT. This booklet provides a list of services and organisations that may be of assistance to those affected by cancer, and should not be considered exhaustive. Unit 1/173 Strickland Crescent Deakin ACT 2600 T: 02 6257 9999 F: 02 6257 5055 W: www.actcancer.org July 2018 Contents Introduction ........................................................2 Support at home ...............................................18 Equipment and home modification ..................18 Treatment centres ..............................................4 Home nursing services ...................................19 Public ..............................................................4 Other practical support and information ..........19 Private .............................................................4 Clinical trials ....................................................4 Prostheses and personal care aids .................20 Other ...............................................................4 -

Australian Football League

COMMUNITY REPORT AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE Tayla Harris of Melbourne takes a high mark during the 2014 women’s match between the Western Bulldogs and the Melbourne Demons at Etihad Stadium. AFL COMMUNITY REPORT 2014 CONTENTS 3 CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE INTRODUCTION FROM THE CEO ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 JIM STYNES COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP AWARD ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 6 AFL OVERVIEW �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 AROUND THE CLUBS ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 23 Adelaide Crows ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������24 Brisbane Lions ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������26 -

Tabled Paper – Department of Regional Development Part B - D

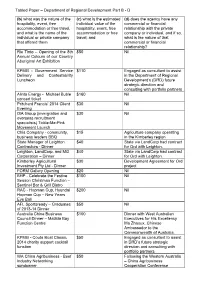

Tabled Paper – Department of Regional Development Part B - D (b) what was the nature of the (c) what is the estimated (d) does the agency have any hospitality, event, free individual value of the commercial or financial accommodation or free travel, hospitality, event, free relationship with the private and what is the name of the accommodation or free company or individual, and if so, individual or private company travel; and what is the nature of that that offered them commercial or financial relationship? Rio Tinto – Opening of the 8th $50 Nil Annual Colours of our Country Aboriginal Art Exhibition KPMG - Government Service $110 Engaged as consultant to assist Delivery and Contestability in the Department of Regional Luncheon Development’s (DRD) future strategic direction and consulting with portfolio partners Alinta Energy - Michael Buble $160 Nil concert ticket Pritchard Francis’ 2014 Client $30 Nil Evening ISA Group (immigration and $30 Nil overseas recruitment specialists) Tickle-Me-Pink Movement Launch Chia Company - community, $15 Agriculture company operating business leaders BBQ in the Kimberley region State Manager of Leighton $40 State via LandCorp had contract Contractors - Dinner for Ord with Leighton. Leighton, LandCorp, and MG $40 State via LandCorp had contract Corporation – Dinner for Ord with Leighton. Kimberley Agricultural $30 Development Agreement for Ord Investment Pty Ltd - Dinner project FORM Gallery Opening $20 Nil BHP - Celebrate the Festive $100 Nil Season Christmas Function – Sentinel Bar & Grill Bistro RAC - Hopman Cup, Hyundai $200 Nil Hopman Cup – New Years Eve Ball AFL Sportsready – Graduates $50 Nil of 2013-14 Dinner Australia China Business $100 Dinner with West Australian Council Dinner – Matilda Bay Executives for His Excellency Function Centre Ma Zhaoux, Chinese Ambassador to the Commonwealth of Australia. -

Annual Review 2019 Supporting Children and Young People with Cancer Contents

annual review 2019 supporting children and young people with cancer contents FROM OUR CHAIRMAN AND CEO our vision 2 2019 AT A GLANCE 4 to support THE CANCER JOURNEY every child, 6 SUPPORT FROM THE MOMENT OF DIAGNOSIS teenager 8 MUSIC THERAPY and young 10 INFORMATION AND SUPPORT adult with 11 FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE cancer, and 12 TRANSFORMING FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE their family, 13 BEREAVEMENT SUPPORT who need us. 14 REDKITE’S CARING COMMUNITY 15 PREMIER PARTNER: COLES our purpose 16 To provide essential support to children LEADING CORPORATE PARTNERS with cancer to ensure the best possible 18 quality of life for them and their family – CELEBRATING AMAZING MILESTONES IN 2019 now and into the future. 19 MAJOR CORPORATE PARTNERS our promise 20 SUPPORTING PARTNERS AND KEY SUPPORTERS You are not alone with cancer. We will 21 listen, respect and respond to you and your family with essential support from PHILANTHROPISTS 22 hospital to home. OUR COMMUNITY OF FUNDRAISERS AND VOLUNTEERS acknowledgement 24 OUR BOARD of country 26 We acknowledge the traditional owners GOVERNANCE AND REGULATION of the land on which we work, and pay 28 our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. SENIOR EXECUTIVE TEAM 29 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS FROM 2019 30 2019 FINANCIALS 32 a message from our Chairman a message from our CEO Jennifer Horrigan Monique Keighery Chairman of the Redkite Board CEO Redkite believes that no family in Australia should face bereavement support packs for grieving families. I couldn’t present the 2019 annual review without greatest value to our donors. We are not afraid to their child’s cancer and treatment alone. -

Talking to Kids About Cancer a Guide for People with Cancer, Their Families and Friends

Talking to Kids About Cancer A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends Coping with cancer DIAGNOSIS CONVERSATIONS Home AFTER TREATMENT CHANGES TREATMENT For information & support, call Talking to Kids About Cancer A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends First published as When a Parent Has Cancer: How to talk to your kids in June 2005. This edition December 2018. © Cancer Council Australia 2018. ISBN 978 1 925651 39 3 Talking to Kids About Cancer is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy is up to date. Editor: Jenny Mothoneos. Designer: Eleonora Pelosi. Printer: SOS Print + Media Group. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Cancer Information Working Group initiative. We thank the reviewers of this book: Professor Kate White, Chair of Nursing, The University of Sydney, NSW; Sarah Ellis, Psychologist, Behavioural Sciences Unit, Kids with Cancer Foundation, Sydney Children’s Hospital, NSW; Kate Fernandez, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council SA; Chandra Franken, Program Manager – NSW & ACT, Starlight Children’s Foundation, NSW; John Friedsam, General Manager of Divisions, CanTeen, NSW; Keely Gordon-King, Cancer Counselling Psychologist, Cancer Council Queensland; Stephanie Konings, Research Officer, CanTeen, NSW; Sally and Rosie Morgan, Consumers; Dr Pandora Patterson, General Manager, Research and Youth Cancer Services, Canteen, and Adjunct Associate Professor, Cancer Nursing Research Unit, The University of Sydney, NSW and Visiting Professor, Faculty of Health and Life Sciences, Coventry University, UK; Suzanne Rumi, Consumer; Michael Sieders, Primary School Program Manager, Camp Quality. -

The Top 20 Most Valuable Australian Sports Brands

BRANDFINANCE ® THE TOP 20 MOST VALUABLE AUSTRALIAN SPORTS BRANDS THE 1ST CONCISE REPORT OF AUSTRALIA’S MOST VALUABLE BRANDS | DECEMBER 2013 2 | BRANDFINANCE® THE TOP 20 MOST VALUABLE AUSTRALIAN SPORTS BRANDS | DECEMBER 2013 BRANDFINANCE ® THE TOP 20 MOST VALUABLE AUSTRALIAN SPORTS BRANDS THE 1ST CONCISE REPORT OF AUSTRALIA’S MOST VALUABLE BRANDS | DECEMBER 2013 Contents BRANDFINANCE® 2 Contents THE TOP 20 4 Executive Summary MOST VALUABLE 5 The Top 20: Results Table 6 Brand Finance: What are Australia’s AUSTRALIAN Top 20 Most Valuable Sports Brands SPORTS BRANDS 8 The Top 10 Profiles The BrandFinance® The Top 20 13 Sponsorship in Australia Most Valuable Australian Sports Brands is published by Brand 14 Global Intangible Finance Tracker Finance plc and is the 1st concise 16 Brand Ratings report of Australia’s Most Valuable Brands 18 Brand Finance Services 20 Brand Finance Methodology 22 Bespoke Reports 23 Contacts Brand Finance plc Level 11, 37 York Street, Sydney 2000, Australia Tel: +61 2 8236 8900 Fax: +61 2 9290 1740 www.brandfinance.com [email protected] 4 | BRANDFINANCE® THE TOP 20 MOST VALUABLE AUSTRALIAN SPORTS BRANDS | DECEMBER 2013 Executive Summary Executive Summary The table on the following page represents stream of (hypothetical) royalty payments and tax authorities and the courts because Brand Finance’s calculation of the 20 most represents the value of the brand. The trade it calculates brand values by reference to valuable Australian football club brands marks for each team are, on the whole, owned documented, third-party transactions and of 2013 (based on 2012 figures). This year by the central body, but are franchised and secondly, because it can be performed only NRL and AFL teams made the Top used by the clubs. -

JOURNEYS Palliative Care for Children and Teenagers

JOURNEYS Resource List JOURNEYS Palliative Care Australia PO Box 24 Deakin West ACT 2600 t: 02 6232 4433 f: 02 6232 4434 e: [email protected] w: www.palliativecare.org.au Download updates of the Journeys Resource List at www.palliativecare.org.au Resource List CONtENtS Information, support services, and resources ........ 2 Other sources of information and support ...........28 Books .......................................................................28 Audience .......................................................................................... 29 Parents and carers ..................................................................................... 29 Talking to children about dying and death ............................................. 31 Grandparents ............................................................................................ 36 Friends and family ..................................................................................... 36 Teachers ..................................................................................................... 37 Topic ................................................................................................ 38 Bereavement support ............................................................................... 40 Deciding on another child ....................................................................... 40 Funeral planning ....................................................................................... 40 Helping yourself ....................................................................................... -

1 November 2019 Graham Jahn Director of City Planning

1 November 2019 Graham Jahn Director of City Planning, Development and Transport City of Sydney GPO Box 1591 Sydney, NSW, 2001 RE: COMMUNITY OUTCOMES FOR SYDNEY SWANS ADAPTIVE REUSE OF THE ROYAL HALL OF INDUSTRIES Dear Mr Jahn, Thank you for the opportunity to meet on September 26 regarding the City of Sydney’s response to the Sydney Swans SSD application (SSD 9726) for the adaptive reuse of the Royal Hall of Industries (RHI). As an outcome of that meeting, the Club is pleased to provide further information on the significant community use and benefits provided by our plan. Our vision – shared with our project partners represented below - for the community to engage with the RHI is detailed in the following submission. Should you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to get in contact. Yours Sincerely, Tom Harley CEO, Sydney Swans 1. INTRODUCTION By any measure, the Sydney Swans Football Club and NSW Swifts Netball are community organisations. The Swans engage a diverse membership base of more than 60,000, and a fanbase across the country of more than 1.17 million. The organisation has demonstrated an enormous capacity to connect people. Whether it is in the stands on a Saturday afternoon at the SCG; on the fields of Moore Park at dusk for Youth Academy Training; in the classroom supporting Indigenous youth as part of the GO Foundation or down Oxford Street as part of the Mardi Gras festival; so many are connected by the Swans. As affirmed through the Club’s Reconciliation Action Plan and Diversity Action Plan, it is a Club for everyone. -

2020 Annual Report

24 September 2020 The Manager Company Announcements Office Australian Securities Exchange Dear Manager, 2020 ANNUAL REPORT In accordance with the ASX Listing Rules, attached for release to the market is Coles Group Limited’s 2020 Annual Report. This announcement is authorised by the Board. Yours faithfully, Daniella Pereira Company Secretary For more information: Investor Relations Media Mark Howell Meg Rayner Mobile: +61 400 332 640 Mobile: +61 439 518 456 E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Coles Group Limited ABN 11 004 089 936 800 Toorak Road Hawthorn East Victoria 3123 Australia PO Box 2000 Glen Iris Victoria 3146 Australia Telephone +61 3 9829 5111 www.colesgroup.com.au 2020 Annual Report Sustainably feed all Australians to help them lead healthier, happier lives Coles Group Limited ABN 11 004 089 936 Coles Group Limited 2020 Annual Report Coles acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of Country throughout Australia and pays its respects to elders past and present. We recognise their rich cultures and continuing connection to land and waters. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are advised that this document may contain names and images of people who are deceased. All references to Indigenous people in this document are intended to include Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people. DRAFT 21 COL1634_An- nualReport_d31a – Rnd 16 Copy September23, 2020 7:52 PM Forward-looking statements This report contains forward-looking statements in relation to Coles Group Limited (‘the Company’) and its controlled entities (together ‘Coles’ or ‘the Group’), including statements regarding the Group’s intent, belief, goals, objectives, initiatives, commitments or current expectations with respect to the Group’s business and operations, market conditions, results of operations and financial conditions, and risk management practices. -

Cancer in the School Community

Cancer in the School Community A guide for staff members Cancer in the School Community A guide for staff members First published March 2008 © The Cancer Council New South Wales 2008 ISBN 978-1-921041-65-8 Writer and Editor: Laura Wuellner Designer: Suzanne Pye, Starfish Design Cartoonist: Greg Smith Cover art: Katherine Chadwick, Designland Contributor: Carol Fallows Series editor: Alyssa White Director, Cancer Information and Support Services: Gillian Batt Manager, Supportive Care Development Unit: Dr Kendra Sundquist Images on pages 8 and 9 courtesy of The Cancer Council Victoria. Table on pages 18 to 21 and “Gemma” case study on page 43 adapted from When a Parent Has Cancer: how to talk to your kids (The Cancer Council NSW, August 2007, pages 16 to 17 and 21). Acknowledgements We are grateful to many school staff members, parents and young people, whose real-life stories have added to the richness and relevance of this book. We thank the expert reviewers: Warwick Chipman, Professional Officer, NSW Secondary Principals Council; Leigh Kurth, Senior Project and Services Officer, Redkite; Kate Lovelace, Student Health Coordinator, NSW Department of Education and Training; Jeremy Medlock, consumer; Katrina Sheraton-Yu, Education Program Coordinator, Back on Track; Dr Michael Stevens AM FRACP , Senior Staff Specialist, Oncology Unit, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead; Tim Rogers, General Manager, National Services, Redkite; Jane Turner, Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychiatry, The University of Queensland; Maria Twigg, Grant and Projects Manager, Redkite; and Daphne Walshe, Oncology Community Clinical Nurse Consultant. We also thank staff members of private and public schools across NSW, and employees of The Cancer Council NSW. -

Fd164a Docker 01 MAR08

Official Magazine of Fremantle Football Club fremantlefc.com.au Edition 1, March 2008 $3.95 i n c GST PP606264/1022 Fremantle Announces Innovations Partner BigPond, the Fremantle Football Club’s Innovations Partner, will bring Fremantle members and supporters access to exclusive content in season 2008! The partnership will also bring you the very latest from BigPond – so keep an eye on the club’s website www.fremantlefc.com.au and FTV. Season 2008 will see Des Headland provide members and supporters “exclusive” behind Is now available on podcast and is proudly brought the scenes access to see what’s to you by BigPond in season 2008. Now you can happening at the Fremantle listen to FreoRadio when you want – on demand!! Football Club. Using the Telstra “Next G™” mobile With FreoRadio podcasts you will be able to listen phone he will be bringing you the latest news from to player interviews, player and coach media the club as you’ve never seen it before. conferences, news headlines and much, much more. You can now subscribe and listen to FreoRadio when DJ’s Downloads you want to – sent directly to you so you will never Des Headland will also give you his Top 5 downloads miss a thing. Visit www.fremantlefc.com.au and each week from BigPond – his top selections from subscribe to FreoRadio absolutely FREE! movies, music, games sport and ring tones that can be downloaded directly from BigPond. Weekly E-mails from Des Thanks to BigPond, Des Headland will provide an BigPond brings you big time entertainment, all on “exclusive” e-mail following on from the weekend’s demand so you can watch what you want and when game, a game review as well as a preview of the you want it on Next G™ mobiles.