Cancer in the School Community a Guide for Staff Members

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Well After Cancer a Guide for Cancer Survivors, Their Families and Friends

Living Well After Cancer A guide for cancer survivors, their families and friends Practical and support information www.cancerqld.org.au Living Well After Cancer A guide for cancer survivors, their families and friends First published February 2010. Reprinted July 2010. Revised March 2012 © Cancer Council Australia 2012. ISBN 978 1 921 619 57 1 Living Well After Cancer is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy of the booklet is up to date. To obtain a more recent copy, phone Cancer Council Helpline 13 11 20. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Publications Working Group initiative. We thank the reviewers of this booklet: Dr Kate Webber, Cancer Survivorship Research Fellow and Medical Oncologist, NSW Cancer Survivors Centre; Kathy Chapman, Director, Health Strategies, Cancer Council NSW; Janine Deevy, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Care Coordinator, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, QLD; Dr Louisa Gianacas, Clinical Psychologist, Psycho-oncology Service, Calvary Mater Newcastle, NSW; Tina Gibson, Education and Support Officer, Cancer Council SA; A/Prof Michael Jefford, Senior Clinical Consultant at Cancer Council VIC, Consultant Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Clinical Director, Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, VIC; Annie Miller, Project Coordinator, Community Education Programs, Cancer Council NSW; Micah Peters, Project Officer, Education and Information, Cancer Council SA; Janine Porter-Steele, Clinical Nurse Manager, Kim Walters Choices, The Wesley Hospital, QLD; Ann Tocker, Cancer Voices; and A/Prof Jane Turner, Department of Psychiatry, University of Queensland. -

Cancer in Vict Oria St Atistics & Trends 2016

CANCER IN VICTORIA STATISTICS & TRENDS 2016 © Cancer Council Victoria 2017 December 2017, Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne Editors: Vicky Thursfield and Helen Farrugia Suggested citation Thursfield V, Farrugia H. Cancer in Victoria: Statistics & Trends 2016. Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne 2017 Published by Cancer Council Victoria 615 St Kilda Road Melbourne Victoria 3004 Australia T: +61 3 9514 6100 F: +61 3 9514 6751 E: [email protected] W: www.cancervic.org.au For enquiries or more detailed data contact: Vicky Thursfield, Reporting and Quality Assurance Manager, Victorian Cancer Registry T: +61 3 9514 6226 E: [email protected] Cancer in Victoria Statistics & Trends 2016 This report is a compilation of the latest available Victorian cancer statistics. Included in the report are detailed tables on cancer incidence, mortality and survival, and projections of incidence and mortality to 2031. The early pages of the report include a brief overview of cancer in Victoria in 2016, and a selection of easily interpretable graphs which may be reproduced in your own reports and presentations. This information is published in electronic and hard copy form every 12 months. The Victorian Cancer Registry (VCR) plays a vital role in providing cancer data, trends and analysis to stakeholders and the Victorian community. Table of contents Message from the Director 8 Key messages 9 Demography 10-11 Population Age and sex Ethnicity Vital statistics Incidence and mortality overview 12-21 Incidence Age and sex Mortality Most common -

Australian Investment Funds

QV Equities Limited ABN 64 169 154 858 Appendix 4E – Preliminary Final Report For the year ended 30 June 2020 For personal use only QV Equities Limited Appendix 4E 30 June 2020 Preliminary Final Report This preliminary final report is for the year ended 30 June 2020. Results for announcement to the market (All comparisons to the year ended 30 June 2019). Up % $ $ movement Revenue from ordinary activities 14,935,401 811,676 6% Profit from ordinary activities before tax attributable to equity 11,899,749 1,075,543 10% holders Profit from ordinary activities after tax attributable to equity holders 10,478,231 1,090,603 12% Dividend Information Amount per Franked Tax Rate for Share Amount per Franking (Cents) Share (Cents) Interim dividend per share (paid 17 March 2020) 2.2 2.2 30% Final dividend per share (to be paid 18 September 2.2 2.2 30% 2020) Total dividends per share for the year 4.4 4.4 Final dividend dates Ex – dividend date 26 August 2020 Record date 27 August 2020 Payment date 18 September 2020 Dividend Reinvestment Plan The Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) is not operational for the final dividend of 2.2c per share due to the on- market share buy-back currently being executed by the Company. Net tangible assets 30 June 2020 30 June 2019 Net tangible asset backing (per share) before tax $0.94 $1.15 Net tangible asset backing (per share) after tax $0.98 $1.13 Audit For personal use only This report is based on the financial report which has been audited. -

Skin Cancer Prevention Evidence Summary

Skin Cancer Prevention Evidence Summary February 1, 2007 NSW Skin Cancer Prevention Working Group Acknowledgments This paper was prepared as an input into the development of the ‘Reducing the impacts of skin cancer in NSW: Strategic Plan 2007-2009’. The document was developed by the NSW Skin Cancer Prevention Working Group, comprising representatives from The Cancer Council NSW (Anita Tang and Kay Coppa); the Cancer Institute NSW (Trish Cotter and Anita Dessaix) and NSW Health (Jenny Hughes and Nidia Raya Martinez), with support from Margaret Thomas from ARTD Consultants. We would like to thank Dr Bruce Armstrong, Dr Diona Damian and Professor Bill McCarthy for their comments on the draft paper. February 2007 ARTD Pty Ltd Level 4, 352 Kent St Sydney ABN 75 003 701 764 PO Box 1167 Tel 02 9373 9900 Queen Victoria Building Fax 02 9373 9998 NSW 1230 Australia Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Solar ultra violet radiation and health ............................................................................................. 2 2.1 Skin 3 2.2 Immune function 3 2.3 Eyes 4 2.4 Vitamin D 4 3 Skin cancer rates and trends ............................................................................................................ 5 3.1 Melanoma 5 3.1.1 Incidence by age and gender 5 3.1.2 Incidence by location 7 3.1.3 Melanoma mortality and survival rates 8 3.2 Non-melanocytic skin cancer 9 3.3 Burden and cost of skin cancer 10 3.4 Risk factors 11 3.4.1 Skin type and colouring 11 3.4.2 Family history 11 3.4.3 Age 11 3.4.4 Naevi 11 3.4.5 Solar keratoses 12 3.4.6 Exposure to UV radiation 12 4 Sun protection knowledge, attitudes and behaviours ................................................................... -

Skin Cancer Prevention Framework 2013–2017

Skin cancer prevention framework 2013–2017 Skin cancer prevention framework 2013–2017 If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, please phone 9096 0399 using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email: [email protected] This document is available as a PDF on the internet at: www.health.vic.gov.au © Copyright, State of Victoria, Department of Health, 2012 This publication is copyright, no part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 50 Lonsdale St, Melbourne. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. December 2012 (1212003) Print managed by Finsbury Green. Printed on sustainable paper. Foreword Keeping Victorians as well as they can be is important for individuals, families and the community. It is also crucial for a strong economy and a healthy, productive workforce. Skin cancer is a significant burden not only on the Victorian community, but also nationally. Australia has the highest age-standardised incidence of melanoma in the world (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010b). It is the most common form of cancer, with two in three Australians being diagnosed with the disease before the age of 70 (Stiller 2007). Of all cancers, skin cancer represents one of the most significant cost burdens on our health system and is one of the most preventable cancers. Victoria is a leader in skin cancer prevention, achieved through world class research, the innovative and internationally recognised SunSmart program, and policy and legislation reform. -

Nutrition and Cancer a Guide for People with Cancer, Their Families and Friends

Nutrition and Cancer A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends Practical and support information For information & support, call Nutrition and Cancer A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends First published July 1998 as Food and Cancer. This edition June 2019. © Cancer Council Australia 2019. ISBN 978 1 925651 51 5 Nutrition and Cancer is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy is up to date. Editor: Jenni Bruce. Designer: Emma Johnson. Printer: SOS Print + Media Group. Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council NSW on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Cancer Information Subcommittee initiative. We thank the reviewers of this booklet: Jenelle Loeliger, Head of Nutrition and Speech Pathology Department, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, VIC; Rebecca Blower, Public Health Advisor, Cancer Prevention, Cancer Council Queensland, QLD; Julia Davenport, Consumer; Irene Deftereos, Senior Dietitian, Western Health, VIC; Lynda Menzies, A/Senior Dietitian – Cancer Care (APD), Sunshine Coast University Hospital, QLD; Caitriona Nienaber, 13 11 20 Consultant, Cancer Council WA; Janice Savage, Consumer. This booklet is funded through the generosity of the people of Australia. Note to reader Always consult your doctor about matters that affect your health. This booklet is intended as a general introduction to the topic and should not be seen as a substitute for medical, legal or financial advice. You should obtain independent advice relevant to your specific situation from appropriate professionals, and you may wish to discuss issues raised in this book with them. -

A Directory of Support Services for People Affected by Cancer in the ACT

CANCER SERVICES ACT Cancer Services ACT A directory of support services for people affected by cancer in the ACT For cancer information and support call For information and support on cancer and cancer related issues call 13 11 20 Email [email protected] July 2018 13 11 20 Visit www.actcancer.org www.actcancer.org Note to reader All care is taken to ensure that the information in this booklet is accurate at the time of publication. Please note that inclusion of a service in this directory does not imply any endorsement or association of that service by Cancer Council ACT. This booklet provides a list of services and organisations that may be of assistance to those affected by cancer, and should not be considered exhaustive. Unit 1/173 Strickland Crescent Deakin ACT 2600 T: 02 6257 9999 F: 02 6257 5055 W: www.actcancer.org July 2018 Contents Introduction ........................................................2 Support at home ...............................................18 Equipment and home modification ..................18 Treatment centres ..............................................4 Home nursing services ...................................19 Public ..............................................................4 Other practical support and information ..........19 Private .............................................................4 Clinical trials ....................................................4 Prostheses and personal care aids .................20 Other ...............................................................4 -

Living Well After Cancer a Guide for Cancer Survivors, Their Families and Friends

Living Well After Cancer A guide for cancer survivors, their families and friends Practical and support information For information & support, call Living Well After Cancer A guide for cancer survivors, their families and friends First published February 2010. This edition April 2015 © Cancer Council Australia 2015. ISBN 978 1 925136 47 0. Living Well After Cancer is reviewed approximately every three years. Check the publication date above to ensure this copy of the booklet is up to date. Editors: Joanne Bell and Melissa Fagan. Designers: Cove Creative and Emma Powney. Printer: SOS Print + Media Group Acknowledgements This edition has been developed by Cancer Council Queensland on behalf of all other state and territory Cancer Councils as part of a National Publications Working Group initiative. We thank the reviewers of this booklet: A/Prof Jane Turner, Department of Psychiatry, University of Queensland; Polly Baldwin, Cancer Council Nurse, Cancer Council South Australia; Ben Bravery, Cancer Survivor, NSW; Helen Breen, Oncology Social Worker, Shoalhaven Cancer Services, NSW; A/Prof Michael Jefford, Consultant Medical Oncologist, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and Clinical Director, Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre; David Larkin, Clinical Cancer Research Nurse, Canberra Region Cancer Centre; Miranda Park, Clinical Nurse Specialist, Cancer Information and Support Service, Cancer Council Victoria; Merran Williams, Nurse, Bloomhill Integrated Cancer Care, QLD; Iwa Yeung, Physiotherapist, Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD; Danny Youlden, Biostatistician, Viertel Cancer Research Centre, Cancer Council Queensland. We would also like to thank Cancer Council Victoria for permission to adapt its booklet, Life After Cancer: a guide for cancer survivors, as the basis of this booklet. The Victorian booklet was developed with the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. -

Plain Packaging of Tobacco Products

Plain packaging of tobacco products EVIDENCE, DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION Plain packaging of tobacco products EVIDENCE, DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION Contents Executive summary vii WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Introduction 1 Plain packaging of tobacco products: evidence, design and implementation. Part 1. Plain packaging: definition, purposes and evidence 3 1.1 A working definition of plain packaging 4 1.Tobacco Products. 2.Product Packing. 3.Tobacco Industry – legislation. Purposes of plain packaging 8 4.Health Policy. 5.Smoking – prevention and control. 6.Tobacco Use – 1.2 prevention and control. I.World Health Organization. 1.3 The evidence base underlying plain packaging 10 1.3.1 The attractiveness of tobacco products and the advertising function of branding 11 ISBN 978 92 4 156522 6 (NLM classification: WM 290) 1.3.2 Misleading tobacco packaging 12 1.3.3 The effectiveness of health warnings 13 1.3.4 The prevalence of tobacco use 13 © World Health Organization 2016 1.3.5 Expert reviews of the evidence 15 1.3.6 Conclusions 18 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are Additional resources 19 available on the WHO website (http://www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; Part 2. Policy design and implementation 21 email: [email protected]). 2.1 The policy design process 22 2.2 Implementation of plain packaging 25 Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications 2.3 Compliance and enforcement 32 –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be 2.3.1 Delayed compliance and penalties for non-compliance 33 addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website (http://www.who.int/ 2.3.2 Sleeves, stickers, inserts and other devices 34 about/licensing/copyright_form/index.html). -

Australian Football League

COMMUNITY REPORT AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE Tayla Harris of Melbourne takes a high mark during the 2014 women’s match between the Western Bulldogs and the Melbourne Demons at Etihad Stadium. AFL COMMUNITY REPORT 2014 CONTENTS 3 CONTENTS AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE INTRODUCTION FROM THE CEO ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 JIM STYNES COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP AWARD ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 6 AFL OVERVIEW �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 AROUND THE CLUBS ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 23 Adelaide Crows ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������24 Brisbane Lions ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������26 -

Cancer Council Victoria 2013 Annual Review

ANNUAL REVIEW / 2013 Cancer in Victoria: tackling challenges and inspiring change Contents 02 / Message from the President Who we are 03 / Message from the CEO Cancer Council Victoria is a non-profit organisation 04 / Highlights of 2013 involved in cancer research, support, prevention 06 / Research and advocacy. Our singleness of purpose – 09 / Prevention improved cancer outcomes – drives us, and will 13 / Support always be balanced by our deep connection with 16 / McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer the experience of cancer patients and their families. 17 / Fundraising Our mission 19 / Our supporters To reduce the impact of all cancers for all Victorians. 21 / Governance and Finance 22 / Executive Committee (Board) Members Our values 24 / Executive Committee report Excellence, integrity and compassion. 26 / Finance, Risk, Audit and Compliance Committee report About this report 27 / Key financial results This report is designed to give our stakeholders 29 / Appeals Committee report an insight into the diversity of the services delivered 30 / Medical and Scientific Committee report by Cancer Council Victoria. It provides details of 31 / Council our activities during the 2013 calendar year. 32 / Other committees The audited 2013 financial reports are contained 35 / Finding the answers within a separate document, which is available on 36 / The research we fund our website (www.cancervic.org.au). A summary 43 / Research grants awarded in 2013 of the financials is contained within this report. 44 / Thank you to our supporters All donations over $2 are On the cover: Dr Jenni Jenkins and her Their mother was found to carry the gene tax deductable. brother Mark Dunstan have Lynch Syndrome and she died of bowel cancer in 2002. -

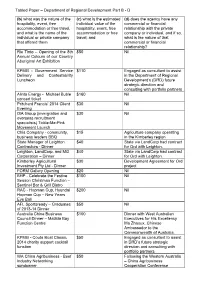

Tabled Paper – Department of Regional Development Part B - D

Tabled Paper – Department of Regional Development Part B - D (b) what was the nature of the (c) what is the estimated (d) does the agency have any hospitality, event, free individual value of the commercial or financial accommodation or free travel, hospitality, event, free relationship with the private and what is the name of the accommodation or free company or individual, and if so, individual or private company travel; and what is the nature of that that offered them commercial or financial relationship? Rio Tinto – Opening of the 8th $50 Nil Annual Colours of our Country Aboriginal Art Exhibition KPMG - Government Service $110 Engaged as consultant to assist Delivery and Contestability in the Department of Regional Luncheon Development’s (DRD) future strategic direction and consulting with portfolio partners Alinta Energy - Michael Buble $160 Nil concert ticket Pritchard Francis’ 2014 Client $30 Nil Evening ISA Group (immigration and $30 Nil overseas recruitment specialists) Tickle-Me-Pink Movement Launch Chia Company - community, $15 Agriculture company operating business leaders BBQ in the Kimberley region State Manager of Leighton $40 State via LandCorp had contract Contractors - Dinner for Ord with Leighton. Leighton, LandCorp, and MG $40 State via LandCorp had contract Corporation – Dinner for Ord with Leighton. Kimberley Agricultural $30 Development Agreement for Ord Investment Pty Ltd - Dinner project FORM Gallery Opening $20 Nil BHP - Celebrate the Festive $100 Nil Season Christmas Function – Sentinel Bar & Grill Bistro RAC - Hopman Cup, Hyundai $200 Nil Hopman Cup – New Years Eve Ball AFL Sportsready – Graduates $50 Nil of 2013-14 Dinner Australia China Business $100 Dinner with West Australian Council Dinner – Matilda Bay Executives for His Excellency Function Centre Ma Zhaoux, Chinese Ambassador to the Commonwealth of Australia.