The Triggering Track-Ways Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian River Sockeye Salmon Study. Alaska Department of Fish And

Volume 21 Study AFS 43-5 STATE OF ALASKA Jay S. Hammond, Governor Annual Performance Report for RUSSIAN RIVER SOCKEYE SALMON STUDY David C. Nelson ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME Ronald 0. Skoog, Commissioner SPORT FISH DIVISION Rupert E. Andrews, Director TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract .............................. 1 Background ............................. 2 Recommendations ...........................6 Objectives ............................. 9 TechniquesUsed .......................... 9 Findings .............................. 10 Smolt Investigations ....................... 10 Creelcensus ........................... 11 Escapement ............................ 17 Relationship of Jacks to Adults ................. 22 Migrational Timing in the Kenai River .............. 22 Managementofthe 1979Fishery .................. 26 Russian River Fish Pass ..................... 31 AgeClass Composition ...................... 32 Early Run Return per Spawner ................... 34 EggDeposition .......................... 40 Fecundity Investigations ..................... 40 Climatological Observations ................... 45 Literature Cited .......................... 45 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. List of Fish Species in the Russian River Drainage .... 8 Table 2. Outmigration of Russian River Sockeye Salmon Smolts by Five-Day Period. 1979 ................. 12 Table 3 . Summary of Sockeye Salmon Smolts Age. Length and Weight Data. 1979 ........................ 13 Table 4. Age Class Composition of the 1979 Sockeye Salmon Smolts Outmigration ...................... -

Diel Horizontal Migration in Streams: Juvenile fish Exploit Spatial Heterogeneity in Thermal and Trophic Resources

Ecology, 94(9), 2013, pp. 2066–2075 Ó 2013 by the Ecological Society of America Diel horizontal migration in streams: Juvenile fish exploit spatial heterogeneity in thermal and trophic resources 1,5 1 1,2 3 1 JONATHAN B. ARMSTRONG, DANIEL E. SCHINDLER, CASEY P. RUFF, GABRIEL T. BROOKS, KALE E. BENTLEY, 4 AND CHRISTIAN E. TORGERSEN 1School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, Box 355020, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA 2Skagit River System Cooperative, 11426 Moorage Way, La Conner, Washington 98257 USA 3Fish Ecology Division, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Seattle, Washington 98112 USA 4U.S. Geological Survey, Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, Cascadia Field Station, School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 USA Abstract. Vertical heterogeneity in the physical characteristics of lakes and oceans is ecologically salient and exploited by a wide range of taxa through diel vertical migration to enhance their growth and survival. Whether analogous behaviors exploit horizontal habitat heterogeneity in streams is largely unknown. We investigated fish movement behavior at daily timescales to explore how individuals integrated across spatial variation in food abundance and water temperature. Juvenile coho salmon made feeding forays into cold habitats with abundant food, and then moved long distances (350–1300 m) to warmer habitats that accelerated their metabolism and increased their assimilative capacity. This behavioral thermoregulation enabled fish to mitigate trade-offs between trophic and thermal resources by exploiting thermal heterogeneity. Fish that exploited thermal heterogeneity grew at substantially faster rates than did individuals that assumed other behaviors. -

Sitka Area Fishing Guide

THE SITKA AREA ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ROADSIDE FISHING .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 ROADSIDE FISHING IN FRESH WATERS .................................................................................................................................... 4 Blue Lake ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Beaver Lake ....................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sawmill Creek .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Thimbleberry and Heart Lakes .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Indian River ....................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Swan Lake ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

What Caused the Sacramento River Fall Chinook Salmon Stock Collapse?

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS T O F C E N O M M T M R E A R P C E E D JULY 2009 U N A I C T I E R D E M ST A AT E S OF WHAT CAUSED THE SACRAMENTO RIVER FALL CHINOOK STOCK COLLAPSE? S.T. Lindley, C.B. Grimes, M.S. Mohr, W. Peterson, J. Stein, J.T. Anderson, L.W. Botsford, D.L. Bottom, C.A. Busack, T.K. Collier, J. Ferguson, J.C. Garza, A.M. Grover, D.G. Hankin, R.G. Kope P.W. Lawson, A. Low, R.B. MacFarlane, K. Moore, M. Palmer-Zwahlen, F.B. Schwing, J. Smith, C. Tracy, R. Webb, B.K. Wells, and T.H. Williams NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-447 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Southwest Fisheries Science Center The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), organized in 1970, has evolved into an agency that establishes national policies and manages and conserves our oceanic, coastal, and atmospheric resources. An organizational element within NOAA, the Office of Fisheries is responsible for fisheries policy and the direction of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). In addition to its formal publications, the NMFS uses the NOAA Technical Memorandum series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible. Documents within this series, however, reflect sound professional work and may be referenced in the formal scientific and technical literature. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS ATMOSPH ND E This TM series is used for documentation and timely communication of preliminary results, interim reports, or special A RI C C I A N D purpose information. -

Estimation of Coho Salmon Escapement in Streams Adjacent To

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Estimation of Coho Salmon Escapement in Streams Adjacent to Perryville and Sockeye Salmon Escapement in Chignik Lake Tributaries, Alaska Peninsula National Wildlife Refuge, 2007 Alaska Fisheries Data Series Number 2007–12 Anchorage Fish and Wildlife Field Office Anchorage, Alaska December 2007 The Alaska Region Fisheries Program of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service conducts fisheries monitoring and population assessment studies throughout many areas of Alaska. Dedicated professional staff located in Anchorage, Juneau, Fairbanks, and Kenai Fish and Wildlife Offices and the Anchorage Conservation Genetics Laboratory serve as the core of the Program’s fisheries management study efforts. Administrative and technical support is provided by staff in the Anchorage Regional Office. Our program works closely with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and other partners to conserve and restore Alaska’s fish populations and aquatic habitats. Additional information about the Fisheries Program and work conducted by our field offices can be obtained at: http://alaska.fws.gov/fisheries/index.htm The Alaska Region Fisheries Program reports its study findings through two regional publication series. The Alaska Fisheries Data Series was established to provide timely dissemination of data to local managers and for inclusion in agency databases. The Alaska Fisheries Technical Reports publishes scientific findings from single and multi-year studies that have undergone more extensive peer review and statistical testing. Additionally, some study results are published in a variety of professional fisheries journals. Disclaimer: The use of trade names of commercial products in this report does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the federal government. -

Roadside Salmon Fishing in the Tanana River Drainage

oadside Salmon Fishing R in the Tanana River Drainage Table of Contents Welcome to Interior Alaska ..........................................................................1 Salmon Biology ...................................................................................................1 Best Places to Fish for King and Chum Salmon ................................................2 Chena River ...............................................................................................2 Salcha River ...............................................................................................3 Other King and Chum Salmon Fisheries .............................................3 Where Can I Catch Coho Salmon? ...............................................................4 cover and front inside photos by: Reed Morisky & Audra Brase The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) administers all programs and activities free from discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, sex, religion, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. The department administers all programs and activities in compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Ameri- cans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility please write: ADF&G ADA Coordinator, P.O. Box 115526, Juneau, AK 99811-5526 U.S. Fish -

Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-78 Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound July 2006 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS Series The Northwest Fisheries Science Center of the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA, uses the NOAA Techni- cal Memorandum NMFS series to issue informal scientific and technical publications when complete formal review and editorial processing are not appropriate or feasible due to time constraints. Documents published in this series may be referenced in the scientific and technical literature. The NMFS-NWFSC Technical Memorandum series of the Northwest Fisheries Science Center continues the NMFS- F/NWC series established in 1970 by the Northwest & Alaska Fisheries Science Center, which has since been split into the Northwest Fisheries Science Center and the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. The NMFS-AFSC Techni- cal Memorandum series is now being used by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Reference throughout this document to trade names does not imply endorsement by the National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA. This document should be cited as follows: Ruckelshaus, M.H., K.P. Currens, W.H. Graeber, R.R. Fuerstenberg, K. Rawson, N.J. Sands, and J.B. Scott. 2006. Independent populations of Chinook salmon in Puget Sound. U.S. Dept. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-NWFSC-78, 125 p. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-78 Independent Populations of Chinook Salmon in Puget Sound Mary H. Ruckelshaus, -

Assessing Extinction Risk for West Coast Salmon Proceedings of the Workshop November 13–15, 1996 Seattle, Washington

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NWFSC-56 Assessing Extinction Risk for West Coast Salmon Proceedings of the Workshop November 13–15, 1996 Seattle, Washington Edited by 1 2 Alec D. MacCall and Thomas C. Wainwright 1 Southwest Fisheries Science Center Santa Cruz Laboratory 110 Shaffer Road Santa Cruz, California 95060 2 Northwest Fisheries Science Center Fish Ecology Division 2032 SE OSU Drive Newport, Oregon 97365 April 2003 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Donald L. Evans, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Vice Admiral Conrad C. Lautenbacher, Jr. USN (Ret), Administrator National Marine Fisheries Service William T. Hogarth, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries ii Most NOAA Technical Memorandums NMFS-NWFSC are available online at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center web site (http://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov) Copies are also available from: National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 phone orders (1-800-553-6847) e-mail orders ([email protected]) iii Contents Preface A. MacCall and T. Wainwright . v Overview . 9 A Review of Essential Factors for Assessing the Extinction Risk of West Coast Salmon Populations: Identifying and Defining Normative Conditions Relevant to Pacific Salmon Stock Assessment. P. R. Mundy . 11 Ecological Issues . 35 Climatic Influences on Salmon Population in the Northeast Pacific. .R . C. Francis and N. J. Mantua . 37 Diversity Issues . 77 Metapopulation Ecology and the Extinction Risk of West Coast Salmonid Populations. M. Mangel . 79 Ecosystem Diversity and the Extinction Risk of Pacific Salmon and Trout. T. H. Williams and G. H. Reeves .. 107 The Genetic Risks of Extinction for Pacific Salmonids. M. Lynch . 117 Artificial Production . -

The World Salmon Farming Industry

CHAPTER V The World Salmon Farming Industry Key Points also limit development in the United States and Canada. Salmon farming appears to have the The origins of salmon farming can be traced back brightest future in Chile due to ideal to fertilization trials in Europe in the second half environmental conditions and a favorable business of the eighteenth century. Hatcheries were climate. Average annual growth rate of the established one century later in both Europe and industry between 1984 and 2004 was 42 percent North America. Hatchery-based enhancement (FAO 2006). programs were introduced at a significant scale only after the 1950s in Japan, the USSR, United The United States has developed advanced States and Canada. The modern techniques of hatchery and marine growout technologies but salmon culture in floating sea cages were initiated ocean-pen production accounts for less than 1 in Norway in the late 1960s. percent of global supply. Alaska placed a permanent moratorium on private, for-profit By the 1980s and 1990s, commercial salmon farmed salmon and salmon trout in 1988, but still farming was well established in many temperate allows enhancement programs, which account for countries around the world (Norway, Scotland, a large share of its harvest. Chile, Canada, etc.). In 1996, salmon aquaculture overcame the salmon fishing industry as the most Increased supplies have generally resulted in important supplier of salmon products worldwide. falling prices. These low prices appear to have By 2004, global production of farmed salmon created more problems for the traditional fisheries exceeded wild harvests by more than one million than for farmed producers since the latter have metric tons (mt). -

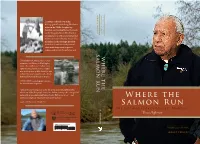

Where the Salmon Run: the Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr

LEGACY PROJECT A century-old feud over tribal fishing ignited brawls along Northwest rivers in the 1960s. Roughed up, belittled, and handcuffed on the banks of the Nisqually River, Billy Frank Jr. emerged as one of the most influential Indians in modern history. Inspired by his father and his heritage, the elder united rivals and survived personal trials in his long career to protect salmon and restore the environment. Courtesy Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission salmon run salmon salmon run salmon where the where the “I hope this book finds a place in every classroom and library in Washington State. The conflicts over Indian treaty rights produced a true warrior/states- man in the person of Billy Frank Jr., who endured personal tragedies and setbacks that would have destroyed most of us.” TOM KEEFE, former legislative director for Senator Warren Magnuson Courtesy Hank Adams collection “This is the fascinating story of the life of my dear friend, Billy Frank, who is one of the first people I met from Indian Country. He is recognized nationally as an outstanding Indian leader. Billy is a warrior—and continues to fight for the preservation of the salmon.” w here the Senator DANIEL K. INOUYE s almon r un heffernan the life and legacy of billy frank jr. Trova Heffernan University of Washington Press Seattle and London ISBN 978-0-295-99178-8 909 0 000 0 0 9 7 8 0 2 9 5 9 9 1 7 8 8 Courtesy Michael Harris 9 780295 991788 LEGACY PROJECT Where the Salmon Run The Life and Legacy of Billy Frank Jr. -

A Review of the Literature on the Upstream Migration of Adult Salmonids

J. Fish Biol. (1969) 1, 85-136 A Review of the Literature on the Upstream Migration of Adult Salmonids J. W. BANKS Department of Zoology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, England (Received 3 December 2968) CONTENTS I. Introduction .. .. .. 86 11. The homing of salmon and the formation of local races . .. .. 86 111. Methods of observing the upstream migration of salmonid fishes . .. 89 IV. Migration in uncontrolled conditions . .. .. .. .. 91 1. Atlantic salmon Saho salar Linn. .. .. .. .. 91 2. Sea trout Salmo trutta Linn. .. .. .. .. .. 93 3. Brown trout Salmo trutfu Linn. .. .. .. .. .. 93 4. Rainbow trout Salmo gairdneri Richardson . .. .. .. 96 5. Sockeye, red, blueback or Kokanee salmon Oncorhynchus nerka (Walbaum) 97 6. Pink or humpback salmon Oncorhynchus gorbuscha (Walbaum) .. 98 7. Chum or dog salmon Oncorhynchus keta (Walbaum) . .. .. 102 V. Migration under controlled conditions . .. .. .. .. 102 1. Atlantic salmon Saho salar Linn. .. .. .. .. 102 2. Sea trout Salmo trutta Linn. .. .. .. .. *. 112 3. Steelhead, rainbow trout Salmo gairdneri Richardson .. .. 112 4. Sockeye salmon Oncorhynchus nerka (Walbaum) . .. .. 112 5. Chinook or spring salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Walbaum) .. 114 VI. Discussion .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 114 1. Rate of Flow . *. .. .. .. .. .. 114 2. Problems of flow at dams, diversions and fish passes .. .. 118 3. Temperature . *. .. .. .. .. .. 120 4. Water quality . .. .. .. .. .. .. 123 5. General weather, wind and tide . .. .. .. .. 124 6. Light intensity . .. .. .. .. .. .. 126 VII. The physiology of salmonids and the control of migration .. .. .. 129 VIII. Summary and conclusions . .. .. .. .. .. 130 References . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 132 85 A 86 J. W. BANKS I. INTRODUCTION The literature on salmonids abounds with instances, both anecdotal and precise, which show that spawning migrations are associated with increased water flows. Doubtless this fact has been a part of fishermen's lore for a very long time. -

Article 1: Salmon Species and Life Cycle

article 1: Salmon Species and Life Cycle This introductory article provides an overview to salmon species in your watershed and their life cycles (and salmon certainly exhibit a remarkable life cycle). This article provides only a brief introduction to these amazing creatures. Many other websites can provide additional information about salmon. This article is divided into five sections: 1. What salmon species are found in Anchor River, Deep Creek, Ninilchik River, and Stariski Creek systems? 2. What are the stages of a salmon's life cycle? 3. What goes on during each life stage? 4. What goes into creating the habitats needed by each salmon life stage? 5. Some details about the life stages of particular salmon species (in a summary table). What salmon species are found in Anchor River, Deep Creek, Ninilchik River, and Stariski Creek systems? Maybe the first piece of information most landowners want to know is which salmon species use their watershed. Table 1 summarizes that information. Images used to illustrate species are in their “ocean bright” phase. As they travel up freshwater streams towards their spawning grounds, salmon change color and shape. These changes are discussed in Section 3 of this article. Table 1 also provides a general idea of when adult salmon of each species travel upstream to spawn. In this first section, we talk about when adult salmon return to their natal streams to spawn (the streams where their lives began). But juvenile salmon are in the river systems ALL times of year, including mid winter. They're found in many habitats depending on species: main channels, side channels, headwaters, lakes.