Bournemouth and the Second World War 1939 – 1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freehold Shop and Flat Investment for Sale

E L L I S A N D P ARTNERS PROPERTY PARTICULARS C.5949 FREEHOLD SHOP AND FLAT INVESTMENT FOR SALE 9 and 9a East Howe Lane • Shop currently trading as beauticians on a 5 year lease from September 2015 Kinson Bournemouth • Rental from Shop £7,500 p.a. Dorset BH10 5HX • Rental from Flat £650 pcm. The Agents for themselves and for the Vendor of this property, whose agents they are, give notice that: (1) These particulars do not constitute, nor constitute any part of , an offer or a contract. (2) All statements contained in these particulars as to this property are made without responsibility on the part of the Agents or Vendor. (3) None of the statements contained in these particulars as to this property are to be relied on as statements or representatives of fact. (4) Any intending purchaser must satisfy himself by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of the statements contained in these particulars. (5) The Vendor does not make or give and neither the Agents nor any person in their employ has any authority to make or give, any representation or warranty whatsoever in relation to this property. OLD LIBRARY HOUSE • 4 DEAN PARK CRESCENT • BOURNEMOUTH BH1 1LY TELEPHONE: 01202 551 821 • FAX: 01202 557 310 • DX 7614 BOURNEMOUTH www.ellis-partners.co.uk ALSO AT BRIGHTON Ellis and Partners Ltd No. 04669426, Ellis and Partners (Bournemouth) Ltd No. 6522485, Ellis and Partners (Brighton) Ltd No. 6522566 Registered in England and Wales. Registered Office: 4 Dean Park Crescent, Bournemouth, Dorset BH1 1LY SITUATION AND DESCRIPTION RATEABLE VALUE – £3,850 East Howe Lane is located just off Kinson Road about Council Tax Band A ½ mile from the main shopping area of Kinson on U.B.R. -

THE RADAR WAR Forward

THE RADAR WAR by Gerhard Hepcke Translated into English by Hannah Liebmann Forward The backbone of any military operation is the Army. However for an international war, a Navy is essential for the security of the sea and for the resupply of land operations. Both services can only be successful if the Air Force has control over the skies in the areas in which they operate. In the WWI the Air Force had a minor role. Telecommunications was developed during this time and in a few cases it played a decisive role. In WWII radar was able to find and locate the enemy and navigation systems existed that allowed aircraft to operate over friendly and enemy territory without visual aids over long range. This development took place at a breath taking speed from the Ultra High Frequency, UHF to the centimeter wave length. The decisive advantage and superiority for the Air Force or the Navy depended on who had the better radar and UHF technology. 0.0 Aviation Radio and Radar Technology Before World War II From the very beginning radar technology was of great importance for aviation. In spite of this fact, the radar equipment of airplanes before World War II was rather modest compared with the progress achieved during the war. 1.0 Long-Wave to Short-Wave Radiotelegraphy In the beginning, when communication took place only via telegraphy, long- and short-wave transmitting and receiving radios were used. 2.0 VHF Radiotelephony Later VHF radios were added, which made communication without trained radio operators possible. 3.0 On-Board Direction Finding A loop antenna served as a navigational aid for airplanes. -

Stage 1 Contribution Assessment Outputs 75

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council and Dorset Council Strategic Green Belt Assessment Stage 1 Study Final report Prepared by LUC December 2020 Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council and Dorset Council Strategic Green Belt Assessment Stage 1 Study Project Number 10946 Version Status Prepared Checked Approved Date 1. Stage 1 Study – Draft N Collins S Young S Young 05.05.20 Report R Swann 2. Stage 1 Study – Draft R Swann R Swann S Young 13.07.20 Final Report S Young 3. Stage 1 Study – Final R Swann R Swann S Young 21.09.20 Report S Young 4. Stage 1 Study – R Swann R Swann S Young 04.12.20 Accessible Version S Young 5. Stage 1 Study – Final R Swann R Swann S Young 15.12.20 Report S Young Bristol Land Use Landscape Design Edinburgh Consultants Ltd Strategic Planning & Glasgow Registered in Assessment London England Development Planning Manchester Registered number Urban Design & 2549296 Masterplanning landuse.co.uk Registered office: Environmental Impact 250 Waterloo Road Assessment London SE1 8RD Landscape Planning & Assessment 100% recycled Landscape paper Management Ecology Historic Environment GIS & Visualisation Contents Strategic Green Belt Assessment - Stage 1 Study Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 5 Background to Study 5 Method Overview 6 Use of Study Outputs 8 Report authors 8 Report Structure 9 Chapter 2 Green Belt Policy and Context 10 National Planning Policy and Guidance 10 Evolution of the South East Dorset Green Belt in Bournemouth, Christchurch, Poole and Dorset 13 The Green Belt in Bournemouth, Christchurch, Poole -

2019-20 Timetables & Maps

operated by TIMETABLES & MAPS 2019-20 unibuses.co.uk operated by CONTENTS HELLO! welcome to Dorchester House | Lansdowne | Cranborne House | 7-16 BOURNEMOUTHFor Bournemouth University and University Talbot Campus the Arts University Bournemouth, we run buses that offer the very best Poole Town Centre | Park Gates | Branksome | University Talbot Campus 21-23 value for money and our services have been tailored to your needs. Southbourne | Pokesdown | Boscombe | Charminster | Winton | 25-30 If you have an annual UNIBUS period pass University Talbot Campus either on our mobile app, clickit2ride, or on our smartcard, theKey, you can use all Westbourne | Bournemouth | Cranborne House | University Talbot Campus 31-32 UNIBUS services as well as all of morebus travel on our buses zone A, excluding nightbus routes N1/N2. with the app or Discounts are available on our nightbuses, Bournemouth | Lansdowne | Winton | Ferndown | Wimborne 35-46 UNIBUS routes U1 U2 U3 U4 if you show your annual pass to the driver Poole | Upper Parkstone | University Talbot Campus | Winton | Moordown | (to view zone A go to unibuses.co.uk). 49-53 morebuses Castlepoint | Royal Bournemouth Hospital all zone A routes refer to morebus.co.uk All UNIBUS services have free WiFi and USB Poole | Newtown | Alderney | Rossmore | Wallisdown | University Talbot Campus | chargers for you to enjoy. 55-63 Winton | Lansdowne | Bournemouth If you only travel occasionally, check out our 10 trip and child fare offers on page 41. for larger print and in other languages, use the ReciteMe software -

87 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

87 bus time schedule & line map 87 Ensbury Park View In Website Mode The 87 bus line (Ensbury Park) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Ensbury Park: 3:25 PM (2) Southbourne: 7:47 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 87 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 87 bus arriving. Direction: Ensbury Park 87 bus Time Schedule 42 stops Ensbury Park Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:25 PM St Peters School, Southbourne Tuesday 3:25 PM St Catherines Road, Southbourne Church Road, Bournemouth Wednesday 3:25 PM Church Road, Southbourne Thursday 3:25 PM Friday 3:25 PM Southbourne Cross Roads, Southbourne 149 Southbourne Overcliff Drive, Bournemouth Saturday Not Operational Avoncliffe Road, Southbourne Belle Vue Road, Bournemouth Clifton Road, Southbourne 87 bus Info Direction: Ensbury Park Tuckton Corner, Southbourne Stops: 42 Trip Duration: 38 min Carbery Avenue, West Southbourne Line Summary: St Peters School, Southbourne, St Carbery Lane, Bournemouth Catherines Road, Southbourne, Church Road, Southbourne, Southbourne Cross Roads, Grand Avenue, West Southbourne Southbourne, Avoncliffe Road, Southbourne, Clifton Southbourne Grove, United Kingdom Road, Southbourne, Tuckton Corner, Southbourne, Carbery Avenue, West Southbourne, Grand Avenue, Fishermans Walk, West Southbourne West Southbourne, Fishermans Walk, West Portman Terrace, United Kingdom Southbourne, Darracott Road, Pokesdown, Pokesdown Station, Pokesdown, Hannington Road, Darracott Road, Pokesdown Pokesdown, Parkwood Road, Boscombe, Ashley Seabourne Road, United Kingdom Road, Boscombe, Bus Station, Boscombe, North Road, Boscombe, Kings Park, Springbourne, Queens Pokesdown Station, Pokesdown Park Hotel, Springbourne, St Marys Church, 922 Christchurch Road, United Kingdom Springbourne, Gilbert Road, Springbourne, Bennett Road, Charminster, Howard Road, Charminster, Hannington Road, Pokesdown Charminster, St. -

Phase 1 Report, July 1999 Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset

MONITORING HEATHLAND FIRES IN DORSET: PHASE 1 Report to: Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions: Wildlife and Countryside Directorate July 1999 Dr. J.S. Kirby1 & D.A.S Tantram2 1Just Ecology 2Terra Anvil Cottage, School Lane, Scaldwell, Northampton. NN6 9LD email: [email protected] web: http://www.terra.dial.pipex.com Tel/Fax: +44 (0) 1604 882 673 Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset Metadata tag Data source title Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset: Phase 1 Description Research Project report Author(s) Kirby, J.S & Tantram, D.A.S Date of publication July 1999 Commissioning organisation Department of the Environment Transport and the Regions WACD Name Richard Chapman Address Room 9/22, Tollgate House, Houlton Street, Bristol, BS2 9DJ Phone 0117 987 8570 Fax 0117 987 8119 Email [email protected] URL http://www.detr.gov.uk Implementing organisation Terra Environmental Consultancy Contact Dominic Tantram Address Anvil Cottage, School Lane, Scaldwell, Northampton, NN6 9LD Phone 01604 882 673 Fax 01604 882 673 Email [email protected] URL http://www.terra.dial.pipex.com Purpose/objectives To establish a baseline data set and to analyse these data to help target future actions Status Final report Copyright No Yes Terra standard contract conditions/DETR Research Contract conditions. Some heathland GIS data joint DETR/ITE copyright. Some maps based on Ordnance Survey Meridian digital data. With the sanction of the controller of HM Stationery Office 1999. OS Licence No. GD 272671. Crown Copyright. Constraints on use Refer to commissioning agent Data format Report Are data available digitally: No Yes Platform on which held PC Digital file formats available Report in Adobe Acrobat PDF, Project GIS in MapInfo Professional 5.5 Indicative file size 2.3 MB Supply media 3.5" Disk CD ROM DETR WACD - 2 - Phase 1 report, July 1999 Monitoring Heathland Fires in Dorset EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lowland heathland is a rare and threatened habitat and one for which we have international responsibility. -

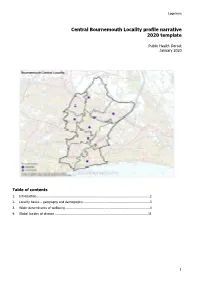

Central Bournemouth Locality Profile Narrative 2020 Template

Logo here Central Bournemouth Locality profile narrative 2020 template Public Health Dorset January 2020 Table of contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 2 2. Locality basics – geography and demography ..................................................................... 3 3. Wider determinants of wellbeing ....................................................................................... 4 4. Global burden of disease ................................................................................................ 11 1 Logo here 1. Introduction Background 1.1 During the summer of 2019 a review of Locality Profile narratives was carried out with key stakeholders across the health and care system in Dorset and Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole (BCP). A summary of findings from the engagement can be found here. 1.2 Informed by stakeholder feedback, this edition of the Locality profile narratives • Provides commentary on a wider range of indicators (from Local Health ), presenting these by life course to increase the emphasis on wider determinants of health and wellbeing • Uses global burden of disease (GBD) 1 as a means of exploring in more detail specific areas of Local Health and general practice based data. 1.3 As with the previous versions of the narratives, these updates are based on data from two key sources: Local Health and General practice based data from https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/general-practice . 1.4 In keeping -

Key Poole Town Centre

n ll rl on e et F t e Rd Sch Rd Dr y H d U Whitehouse Rd e tt R llswat n ille W C W er Rd Po c d 8 h a a m R 4 m M y a a y p 3 R g s y e r m 's W e A a d l y d B B Cl Fitzpain e i k s W W a n Canford C ig 3 a Carters Cottages l ht r Hurn A O L s W r n 0 l o Lambs' 31 A31 Park n k k a Honey 7 B c w N r 3073 d 3 Glissons o Rd e s Farm C n Green d C n w h Lower Russell's L kley L C Barrack Rd s d Park Cottages d Belle Vu r y L Oa e a d s am a R l Copse bs Hampreston s p n y an P Hadria d g c a reen To l Poor e l L n i d d H C Dirty Lane e v F Holmwood n e l a R Wk C Cl n Wimborne a l l Common ammel n L t Oakley o m Coppice t a r n H C y l Higher Russell's L C M al L Park n W Brog S l n r F C i e House Ln o a u k Copse y A349 Ch d H u r r b e D Merley l Harrie C m is s R S r r Dr Merley opw n tc Belle Vue d West e y i u t v Mill St A31 Park e h l t hu D e e First Sch C j r a A31 M l o c Plantation r A Rhubane r Longham h F Parley k e y Floral d Rd b Parley Bsns h Cottage a e s R n O a r c L v Wood Pk r rm i n Rd d den Cl u i k A B o 3 l Pond Chichester W 07 B B Oakley 3 y S ry opw ith o B Merley l Cres C e Coppice Rec l Oakland i Lin l l w d a bu r S w Brie W n Cottage H a e rley Grd g d t n e n i o y B o f n R ds Av o r r i e u e M a g d r er d l le b u k d Rec y B r L H a a R R The n z a Vw o D d ak a e Grd n M Canford C h Shrubbery O w Rd in Sports M e East k d L Ashington Ln er r Magna yd W Fields y o k n le C li k B er l f n 3 End L M c l n Longham Lakes 0 H S W R h 7 Dudsbury C n s a 4 ark Rd n Cl u e P d e Garden Reservoir o y G Layard -

Papers for Dorset LEP Board Meeting 22 November 2018

DORSET LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP BOARD MEETING 22 NOVEMBER 2018 FROM 10.00 AM TO 12.30 PM THE TANK MUSEUM, BOVINGTON AGENDA Time Item Subject/ Title Presenter Recommendation 10.00 1. Apologies and declarations of interest Jim Stewart 10.05 2. Minutes of last meeting and matters arising Jim Stewart and Forward Plan 3. Guest Presentations 10.15 3.1 South West Community Bank Tony Greenham List of all recommendations for decision from Dorset LEP Board 10.30 3.2 Studio Egret West Talbot Quarter Proposals Darryl Tidd/ For information as the Talbot quarter proposals are now being by Talbot Village Trust James Gibson/ progressed, as well as an opportunity for early engagement. Norman Apsley/ David West 4. Strategy 10.45 4.1 Innovation Strategy Rob Dunford/ LEP Board to note the progress to date and timeline for completion of Neil Darwin the Innovation Strategy 11.00 4.2 Horizon 2038 Lorna Carver None 11.15 4.3 Local Industrial Strategy Lorna Carver 1. Board Members to note the progress 2. Board members to volunteer to be part of the steering group. 3. Please note the diagram to summarise the process. 11.30 4.4 Partnership Working Rob Dunford To note the progress made with regional partnership working and to continue to support the approach. 11.40 4.5 Governance Update Lorna Carver Dorset LEP Board to note the progress that has been made to enhance Dorset LEP’s governance and transparency. Page 1 of 52 5. Delivery 11.50 5.1 Delivery Update Rob Dunford Confidential - Commercially Sensitive 12.00 5.2 Project Pipeline Update Rob Dunford Confidential - Commercially Sensitive 12.15 5.3 Delivery Plan Lorna Carver Dorset LEP Board supports the Dorset LEP Team to create a delivery plan in the format required by Government by the deadline of April 2019. -

Event Organiser's Guide

BOURNEMOUTH FOR BUSINESS Event Organiser's Guide Welcome to Bournemouth With its panoramic coastline, iconic architecture, meandering gardens, vibrant shopping experience and city-style restaurants and bars, Bournemouth strikes the perfect balance between work and play. This handy guide will help you discover the hidden – and not so hidden – gems of our iconic town, giving you a bird’s eye view of the bountiful best bits. Contents 2-3 Not just Britain’s best beach… 12-40 Our venues 4 Immerse yourself in the 41-52 Support services great outdoors 53 Event services listings 5 Serious about green 54-65 Dining 6 Entrepreneurial at heart 66-67 Accommodation listings 7 Boomtown stats 68-69 Map 8 Work hard, play hard 70 Getting here & Contact us 9 City-style dining by the beach 71 Testimonials 10-11 Business Events Bournemouth BusinessEventsBournemouth.org.uk 1 Not just Britain’s best beach… Whilst there’s so much more to Bournemouth than its beach, it’s a pretty good space, which conceals an eclectic mix of its canopied walkway, whilst the Square place to start. Voted the UK's best beach in TripAdvisor's Travellers' Choice Awards street food and seasonal entertainment, from boasts street entertainment, live music two years in a row, the seven-mile stretch of uninterrupted golden sand and art exhibitions to festivals to ice-skating. and places to watch the world go by. promenade is a hub of activity all year round. The town itself is a traffic-free hub of high And when it’s time to unwind, the town’s The fact that Bournemouth enjoys a unique Pier Approach, with its vibrant open space, street favourites and independent boutiques. -

Talbot Campus

P A3 C 0 B H Haddon 49 7 E Wallisdown D STROUDEN ROAD A D N B 4 D R R R FEVERSHAM AVE GAL RD R R Hill 3 N PINE ROAD PORTLAN M D D R O WALLISDOWN Playing Field ROAD O A R I A D N E N A T O T W R O S Cemetery A R T RD D S LL O CA P S RKWAY E MOSSLEY AV I N I T R PA DRI V SD LV POR E ROU A 0 I TL N D O NORTON RD N P R AND RD R E E W D R I I N V 4 A N D D N A V E E W R R PRIVET RD E V M N 0 O A N O AD EDGEHILL U U R 3 O E B TALBOT Y LUTHER ROAD R O E FERNSIDE RD A D A R A R BOUNDARY CAMPUS G RD H R C E A EEN LAND D UNIVERSITY WITHERMOOR RD RUT U ROAD E N BRYANT ROAD UNIVERSITY WA D D R OAD R R O B R E PLAYING FIELDS L GLENMOOR N P AD R LIS N RIDLEY RD ACKENDA V DO R LE A R W U F N RD O LATIMER RD IRBA E R O P N B K D B FIRSGLEN M R D ROW R D R M TALBOT DRIVE BA D ACLAND RD K 8 I N KE A R 3 L R P 3 E BOUNDARY W MARKHAM RD Q U N ’ S A F 3 S E E A WYCLIFF RD ABBOTT RD SOMERLEY RD 6 T BEMISTER RD R 0 G FREDERICA RDSTANFIELD HANKINSON RD D C 3 E A N Talbot P B S O ’ P 3 E E 0 D HANKINSON RD D SEDGLEY RD D N A R V 049 R D I 4 3 TALBOT O A O G Heath 9 A CARD R B R R O IGA D E N L E D RD MAXWELL RD D ’ B Queen’s Park T A S W A T R R S V I R A O A I P N O 0 D TALBOT D A V A D U MAXWELL RD R W R 4 W O R G V BURNHAM D N R PARKER RD O O ESTDRIVE O T H A W 0 Y BRYANSTONE RD T R CECIL AVENUE K W H R T T C R 3 A R E E O E A Y O L L C P N A A M S T D B L A E I U S N R O S ’ E FER G 3 K STIRLING T A D R R ST ALBAN’S AVENUE P 4 N L R N R 7 D I D E E T A B FITZHARRIS AVENUE T P N A H W P O I ROAD I U R D TALBOT AVENUEL L Superstore A ROSLIN RD STH M RM L R -

571 Write Up.Pdf

This paper comprises a brief history of the origins and early development of radar meteorology. Therefore, it will cover the time period from a few years before World War II through about the 1970s. The earliest developments of radar meteorology occurred in England, the United States, and Canada. Among these three nations, however, most of the first discoveries and developments were made in England. With the exception of a few minor details, it is there where the story begins. Even as early as 1900, Nicola Tesla wrote of the potential for using waves of a frequency from the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum to detect distant objects. Then, on 11 December 1924, E. V. Appleton and M.A.F. Barnett, two Englishmen, used a radio technique to determine the height of the ionosphere using continuous wave (CW) radio energy. This was the first recorded measurement of the height of the ionosphere using such a method, and it got Appleton a Nobel Prize. However, it was Merle A. Tuve and Gregory Breit (the former of Johns Hopkins University, the latter of the Carnegie Institution), both Americans, who six months later – in July 1925 – did the same thing using pulsed radio energy. This was a simpler and more direct way of doing it. As the 1930s rolled on, the British sensed that the next world war was coming. They also knew they would be forced to defend themselves against the German onslaught. Knowing they would be outmanned and outgunned, they began to search for solutions of a technological variety. This is where Robert Alexander Watson Watt – a Scottish physicist and then superintendent of the Radio Department at the National Physical Laboratory in England – came into the story.