The Cadenza: Performance Practice in Alto Trombone Concerti of the Eighteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

Totalartwork

spınetL an Experiment on Gesamtkunstwerk Totalartwork Thursday–Friday October 21–22, 2004 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art www.birgitramsauer.net/spinet 21 October 22 October Panel Discussion 6–7pm Panel Discussion 6–7pm Contemporary artists and an The Gesamtkunstwerk (Totalartwork) historical instrument in the 21st century Moderator: Moderator: Christopher McIntyre Christopher McIntyre Associate Music Curator, The Kitchen Associate Music Curator, The Kitchen Participants include: Jens Barnieck, pianist Participants include: Enrico Cocco, composer Jens Barnieck, pianist Gearoid Dolan, artist Enrico Cocco, composer Kyle Gann, composer, critic Gearoid Dolan, artist Thea Herold, word performer Thea Herold, word performer Charlie Morrow, composer Charlie Morrow, composer Aloisia Moser, philosopher Wolf-Dieter Neupert, company Wolf-Dieter Neupert, company for historical instruments for historical instruments Georg Nussbaumer, composer Georg Nussbaumer, composer Birgit Ramsauer, artist Birgit Ramsauer, artist Kartharina Rosenberger, Katharina Rosenberger, composer composer David Grahame Shane, architect, urbanist, author Concert 8pm Gerd Stern, poet and artist Gloria Coates Abraham Lincoln’s Performance 8pm Cooper Union Address* Frieder Butzmann Stefano Giannotti Soirée pour double solitaires * L’Arte des Paesaggio Charlie Morrow, alive I was silent Horst Lohse, Birgit’s Toy* and in death I do sing* Intermission Enrico Cocco, The Scene of Crime* Heinrich Hartl, Cemballissimo Aldo Brizzi, The Rosa Shocking* Katharina Rosenberger, -

2. Kammerkonzert „HAYDNS ENTDECKER“ Eine Hommage an Den Komponisten Johann Georg Reutter So 13

Generalmusikdirektor Axel Kober PROGRAMM 2. Kammerkonzert „HAYDNS ENTDECKER“ Eine Hommage an den Komponisten Johann Georg Reutter So 13. Oktober 2019, 19.00 Uhr Philharmonie Mercatorhalle Hana Blažíková Sopran Barockensemble nuovo aspetto Ermöglicht durch Kulturpartner Gefördert vom Duisburger Kammerkonzerte Johann Georg Reutter Sonntag, 13. Oktober 2019, 19.00 Uhr „Soletto al mio caro“, Arie aus „Alcide trasformato in dio“ Philharmonie Mercatorhalle für Sopran, Salterio und Basso continuo (1729) Giuseppe Porsile Andante aus „Il giorno felice“ (1723) Hana Blažíková Sopran Francesco Bartolomeo Conti (1681-1732) „Dei colli nostri", nuovo aspetto: Arie aus „Il trionfo dell’amicizia e dell’amore“ für Sopran, Christian Binde Horn Mandoline, Harfe, Baryton und Basso continuo (1711) Jörg Schultess Horn Helena Zemanová Violine Pause Frauke Pöhl Violine Corina Golomoz Viola Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) / Henri Compan Elisabeth Seitz Salterio „Je ne vous disais point: j’aime“ Johanna Seitz Harfe aus „Le Fat dupé“ für Sopran und Harfe Michael Dücker Laute, Mandolino Ulrike Becker Violoncello, Barytono Johann Georg Reutter „Dura legge a chi t’adora“, Arie aus „Archidamia“ Francesco Savignano Wiener Bass für Sopran, Salterio, Laute und Basso continuo (1727) Luca Quintavalle Cembalo Joseph Haydn Aus: Sinfonie C-Dur „Le Distrait“ Hob. I:60 Programm in der Kammermusikfassung für Harfe, Violine, Viola und Bass von Meingosus Gaelle (1774/1809) Adagio – Finale Johann Georg Reutter (1708-1772) „Dal nostro nuovo aspetto“, „The Inspired Bard“ Hob. XXXIb:25 aus -

Performing Michael Haydn's Requiem in C Minor, MH155

HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America Volume 9 Number 2 Fall 2019 Article 4 November 2019 Performing Michael Haydn's Requiem in C minor, MH155 Michael E. Ruhling Rochester Institute of Technology; Music Director, Ensemble Perihipsous Follow this and additional works at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal Recommended Citation Ruhling, Michael E. (2019) "Performing Michael Haydn's Requiem in C minor, MH155," HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America: Vol. 9 : No. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://remix.berklee.edu/haydn-journal/vol9/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Research Media and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in HAYDN: The Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America by an authorized editor of Research Media and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Ruhling, Michael E.. “Performing Michael Haydn’s Requiem in C minor, MH155.” HAYDN: Online Journal of the Haydn Society of North America 9.2 (Fall 2019), http://haydnjournal.org. © RIT Press and Haydn Society of North America, 2019. Duplication without the express permission of the author, RIT Press, and/or the Haydn Society of North America is prohibited. Performing Michael Haydn’s Requiem in C minor, MH155 by Michael E. Ruhling Rochester Institute of Technology Music Director, Ensemble Perihipsous I. Introduction: Historical Background and Acknowledgements. Sigismund Graf Schrattenbach, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, died 16 December 1771, at the age of 73. Johann Michael Haydn, who had been in the service of the Prince-Archbishop since 1763, serving mainly as concertmaster, received the charge to write a Requiem Mass for the Prince-Archbishop’s funeral service. -

1 the Recitative in Trombone Music William J. Stanley ©2019 at First

The Recitative in Trombone Music William J. Stanley ©2019 At first glance, the linking of recitative with a trombone might seem contradictory. After all, the recitative is found most often in opera and oratorio as a speech like style of musical expression performed by singers. But over the past several years, as I was preparing music for performance and assisting students with their preparation, recurring examples of recitative in trombone music appeared more than occasionally. Trombonists will readily recognize concertos by Ferdinand DaviD (1837), Launy Grøndahl (1924) and Gordon Jacob (1956) as often performed pieces that include a recitative. Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov has provided two well-known solo recitatives for the orchestral second trombonist in Scheherazade, op. 35, and La Grande Pâque Russe, op. 36. These works and several others prompted, at first, an informal list to simply satisfy my curiosity. A subsequent more thorough search has found a large number of works that contain a recitative. To date well over 100 pieces have been discovereD. These span over 250 years and include unaccompanied solos, orchestral solos, pieces with piano, organ, orchestra and/or band accompaniment, and in various ensemble settings for tenor, bass and alto trombones. While that number and breadth of works might be surprising to some, the fact that composers have continued to use vocally influenceD materials in trombone music should be of no surprise to trombonists. We know there is the long tradition of the use of the trombone in vocal settings throughout its history. A thorough examination of this practice goes well beyond the scope and intent of this study, but it is widely known that the trombone was commonly used throughout the sixteenth- and seventeenth-centuries as an accompanying and doubling instrument in sacred settings with choirs. -

Functional Training for All Styles

Modern Voice Pedagogy Functional Training For All Styles By Elizabeth Ann Benson ue to the rising number of consolidated for improved efficiency including folk, rock, pop, heavy metal, collegiate musical theater and and camaraderie. Some elements of R&B and many more. These programs contemporary commercial vocal technique that may be trained need voice teachers who can provide music (CCM) programs, there independently of musical style include functional vocal technique so students is increasing demand for teachers of vibrato, posture and alignment, onsets, can safely and consistently produce the singing to provide diverse and versatile agility and registration. This article broad spectrum of sounds required in training beyond the classical aesthetic. will argue in favor of shifting to func many different styles of music. When the vocal techniques of classi tional voice training as core technical cal and CCM singing are identified training to effectively serve classical, Vocal Technique in terms of function, there is much musical theater and contemporary In 1975, Cornelius Reid encour in common. It is only in the appli commercial voice students within one aged voice pedagogues to distinguish cation of vocal technique to musical studio. between “art” and “function,” where repertoire that significant differences Musical theater singing; includes a art is “the use of skill and imagina occur, according to genre. Rather than multitude of musical sub-genres, from tion in the production of things of running independent tracks of vocal legit musical theater to contempo beauty,” and function is “the natural study in classical, music theater and rary hard rock. A study by Kathryn action characteristic of a mechanical commercial/popular singing, many Green et al. -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the Rise of the Cäcilien-Verein

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein Nicholas Bygate Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bygate, Nicholas, "Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 955. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/955 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nineteenth Century Sacred Music: Bruckner and the rise of the Cäcilien-Verein By Nicholas Bygate Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Bertil van Boer Dr. Timothy Fitzpatrick Dr. Ryan Dudenbostel GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Interim Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

Mozart's Transformation of the Cadenza in the First Movements Of

Mozart’s Transformation of the Cadenza in the First Movements of his Piano Concertos – Vincent C. K. Cheung Mozart’s piano concertos are often acclaimed to be the composer’s finest instrumental works. Thousands of musicians, including Beethoven and Brahms, have been amazed by his piano concertos, and for this reason, many studies on Mozart’s concertos have been done. The structure of his concertos, and especially the structure of the first movements, has been analyzed thoroughly by many musicologists, notably C. Girdlestone1 and A. Hutchings.2 However, few of them pay serious attention to Mozart’s original cadenzas for his piano concertos. This essay is an attempt to illustrate briefly how Mozart contributes to the evolution of the cadenza by ensuring it to be an essential part of the structure of the first movement, and by using it to reinforce the equality between the solo and the tutti. I. Background: the state of the cadenza around 1750 and Mozart’s transformation of the cadenza We shall begin by examining the evolution of the cadenza as a genre up to Mozart’s time. A cadenza can be defined as “a virtuoso passage inserted near the end of a concerto movement or aria, usually indicated by the appearance of a fermata over an inconclusive chord such as the tonic 6-4.”3 However, the history of cadenza can be traced back to a long time before the emergence of concerto or opera: composers since the Medieval era tended to prolong the endings of their pieces with embellishments in order to amplify the effect of the closing cadence.4 The improvised cadenza in the modern sense did not appear until the early Baroque period when the da capo aria and the concerto became popular: 1 CUTHBERT GIRDLESTONE, Mozart and his Piano Concertos (New York: Dover, 1964). -

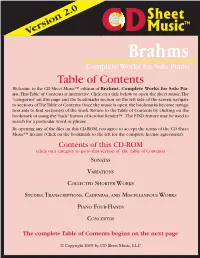

Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ Edition of Brahms, Complete Works for Solo Pia- No

Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 1 Brahms Complete Works for Solo Piano Table of Contents Welcome to the CD Sheet Music™ edition of Brahms, Complete Works for Solo Pia- no. This Table of Contents is interactive. Click on a title below to open the sheet music. The “categories” on this page and the bookmarks section on the left side of the screen navigate to sections of The Table of Contents.Once the music is open, the bookmarks become naviga- tion aids to find section(s) of the work. Return to the Table of Contents by clicking on the bookmark or using the “back” button of Acrobat Reader™. The FIND feature may be used to search for a particular word or phrase. By opening any of the files on this CD-ROM, you agree to accept the terms of the CD Sheet Music™ license (Click on the bookmark to the left for the complete license agreement). Contents of this CD-ROM (click on a category to go to that section of the Table of Contents) SONATAS VARIATIONS COLLECTED SHORTER WORKS STUDIES, TRANSCRIPTIONS, CADENZAS, AND MISCELLANEOUS WORKS PIANO FOUR-HANDS CONCERTOS The complete Table of Contents begins on the next page © Copyright 2005 by CD Sheet Music, LLC Sheet TM Version 2.0 CDMusic 2 SONATAS Sonata No. 1 in C Major, Op. 1 Sonata No. 2 in F# Minor, Op. 2 Sonata No. 3 in F Minor, Op. 5 VARIATIONS Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Op. 9 Variations on an Original Theme, Op. 21, No. 1 Variations on a Hungarian Song, Op. -

Classic Terms

Classic Terms Alberti Bass: "Broken" arpeggiated triads in a bass line, common in many types of Classic keyboard music; named after Domenico Alberti (1710-1740) who used it extensively but did not invent it. Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Bel Canto: (Italian for "beautiful singing") An Italian singing tradition primarily in opera seria and opera buffa in the late17th- to early-19th century. Characterized by seamless phrasing (legato), great breath control, flexibility, tone, and agility. Most often associated with singing done in the early-Romantic operas of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. Cadenza: An improvised or written-out ornamental virtuosic passage played by a soloist in a concerto. In Classic concertos, a cadenza occurs at a dramatic moment before the end of a movement, when the orchestra stops so the soloist can play in free time, and then after the cadenza is finished the orchestra reenters to bring the movement to its conclusion. Castrato The term for a male singer who was castrated before puberty to preserve his high soprano range (this practice in Italy lasted until the late 1800s). Today, the rendering of castrato roles is problematic because it requires either a male singing falsetto (weak) or a mezzo-soprano (strong, but woman must impersonate a man). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Empindsam: (German for "sensitive") The term used to describe a highly-expressive style of German pre- Classic/early Classic instrumental music, that was intended to intensely express true and natural feelings, featuring sudden contrasts of mood.