Evolutionary Epistemology | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Kinds and Concepts: a Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account

Natural Kinds and Concepts: A Pragmatist and Methodologically Naturalistic Account Ingo Brigandt Abstract: In this chapter I lay out a notion of philosophical naturalism that aligns with prag- matism. It is developed and illustrated by a presentation of my views on natural kinds and my theory of concepts. Both accounts reflect a methodological naturalism and are defended not by way of metaphysical considerations, but in terms of their philosophical fruitfulness. A core theme is that the epistemic interests of scientists have to be taken into account by any natural- istic philosophy of science in general, and any account of natural kinds and scientific concepts in particular. I conclude with general methodological remarks on how to develop and defend philosophical notions without using intuitions. The central aim of this essay is to put forward a notion of naturalism that broadly aligns with pragmatism. I do so by outlining my views on natural kinds and my account of concepts, which I have defended in recent publications (Brigandt, 2009, 2010b). Philosophical accounts of both natural kinds and con- cepts are usually taken to be metaphysical endeavours, which attempt to develop a theory of the nature of natural kinds (as objectively existing entities of the world) or of the nature of concepts (as objectively existing mental entities). However, I shall argue that any account of natural kinds or concepts must an- swer to epistemological questions as well and will offer a simultaneously prag- matist and naturalistic defence of my views on natural kinds and concepts. Many philosophers conceive of naturalism as a primarily metaphysical doc- trine, such as a commitment to a physicalist ontology or the idea that humans and their intellectual and moral capacities are a part of nature. -

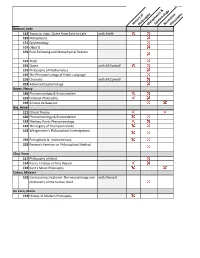

History of Philosophymetaphysics & Epistem Ology Norm Ative

HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Azzouni, Jody 114 Topics in Logic: Quine from Early to Late with Smith 120 Metaphysics 131 Epistemology 191 Objects 191 Rule-Following and Metaphysical Realism 191 Truth 191 Quine with McConnell 191 Philosophy of Mathematics 192 The Phenomenology of Public Language 195 Chomsky with McConnell 292 Advanced Epistemology Bauer, Nancy 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 191 Feminist Philosophy 192 Simone de Beauvoir Baz, Avner 121 Ethical Theory 186 Phenomenology & Existentialism 192 Merleau Ponty Phenomenology 192 The Legacy of Thompson Clarke 192 Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations 292 Perceptions & Indeterminacy 292 Research Seminar on Philosophical Method Choi, Yoon 117 Philosophy of Mind 164 Kant's Critique of Pure Reason 192 Kant's Moral Philosophy Cohen, Michael 192 Conciousness Explored: The neurobiology and with Dennett philosophy of the human mind De Caro, Mario 152 History of Modern Philosophy De HistoryPhilosophy of MetaphysicsEpistemology & NormativePhilosophy Car 191 Nature & Norms 191 Free Will & Moral Responsibility Denby, David 133 Philosophy of Language 152 History of Modern Philosophy 191 History of Analytic Philosophy 191 Topics in Metaphysics 195 The Philosophy of David Lewis Dennett, Dan 191 Foundations of Cognitive Science 192 Artificial Agents & Autonomy with Scheutz 192 Cultural Evolution-Is it Darwinian 192 Topics in Philosophy of Biology: The Boundaries with Forber of Darwinian Theory 192 Evolving Minds: From Bacteria to Bach 192 Conciousness -

The Fourth Perspective: Evolution and Organismal Agency

The Fourth Perspective: Evolution and Organismal Agency Johannes Jaeger Complexity Science Hub (CSH), Vienna, Josefstädter Straße 39, 1080 Vienna Abstract This chapter examines the deep connections between biological organization, agency, and evolution by natural selection. Using Griesemer’s account of the re- producer, I argue that the basic unit of evolution is not a genetic replicator, but a complex hierarchical life cycle. Understanding the self-maintaining and self-pro- liferating properties of evolvable reproducers requires an organizational account of ontogenesis and reproduction. This leads us to an extended and disambiguated set of minimal conditions for evolution by natural selection—including revised or new principles of heredity, variation, and ontogenesis. More importantly, the con- tinuous maintenance of biological organization within and across generations im- plies that all evolvable systems are agents, or contain agents among their parts. This means that we ought to take agency seriously—to better understand the con- cept and its role in explaining biological phenomena—if we aim to obtain an or- ganismic theory of evolution in the original spirit of Darwin’s struggle for exis- tence. This kind of understanding must rely on an agential perspective on evolu- tion, complementing and succeeding existing structural, functional, and processual approaches. I sketch a tentative outline of such an agential perspective, and present a survey of methodological and conceptual challenges that will have to be overcome if we are to properly implement it. 1. Introduction There are two fundamentally different ways to interpret Darwinian evolutionary theory. Charles Darwin’s original framework grounds the process of evolution on 2 the individual’s struggle for existence (Darwin, 1859). -

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy, VI-1 | 2014 Popular Science, Pragmatism, and Conceptual Clarity 2

European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy VI-1 | 2014 The Reception of Peirce in the World Popular Science, Pragmatism, and Conceptual Clarity Oliver Belas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/514 DOI: 10.4000/ejpap.514 ISSN: 2036-4091 Publisher Associazione Pragma Electronic reference Oliver Belas, « Popular Science, Pragmatism, and Conceptual Clarity », European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy [Online], VI-1 | 2014, Online since 08 July 2014, connection on 16 March 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/514 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ejpap.514 This text was automatically generated on 16 March 2020. Author retains copyright and grants the European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy right of first publication with the work simultaneously licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Popular Science, Pragmatism, and Conceptual Clarity 1 Popular Science, Pragmatism, and Conceptual Clarity Oliver Belas Introduction 1 One of popular science’s primary functions is to make what would otherwise be inaccessible, specialist knowledge accessible to the lay reader. But popular science puts its imagined reader in something of a dilemma, for one does not have to look very far to find bitter argument among science writers; argument that takes place beyond the limits of the scientific community: witness the ill-tempered exchanges between Mary Midgley and Richard Dawkins in the journal Philosophy in the late seventies and early eighties; or, from the mid-nineties, the surly dialogue of Stephen Jay Gould, Daniel Dennett, and others in The New York Review of Books (see below and Works Cited). -

The Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85128-2 - The Cambridge Companion to the Philosophy of Biology Edited by David L. Hull and Michael Ruse Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to THE PHILOSOPHY OF BIOLOGY The philosophy of biology is one of the most exciting new areas in the field of philosophy and one that is attracting much attention from working scientists. This Companion, edited by two of the founders of the field, includes newly commissioned essays by senior scholars and by up-and- coming younger scholars who collectively examine the main areas of the subject – the nature of evolutionary theory, classification, teleology and function, ecology, and the prob- lematic relationship between biology and religion, among other topics. Up-to-date and comprehensive in its coverage, this unique volume will be of interest not only to professional philosophers but also to students in the humanities and researchers in the life sciences and related areas of inquiry. David L. Hull is an emeritus professor of philosophy at Northwestern University. The author of numerous books and articles on topics in systematics, evolutionary theory, philosophy of biology, and naturalized epistemology, he is a recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Michael Ruse is professor of philosophy at Florida State University. He is the author of many books on evolutionary biology, including Can a Darwinian Be a Christian? and Darwinism and Its Discontents, both published by Cam- bridge University Press. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he has appeared on television and radio, and he contributes regularly to popular media such as the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Playboy magazine. -

May 03 CI.Qxd

Philosophy of Chemistry by Eric Scerri Of course, the field of compu- hen I push my hand down onto my desk it tational quantum chemistry, does not generally pass through the which Dirac and other pioneers Wwooden surface. Why not? From the per- of quantum mechanics inadver- spective of physics perhaps it ought to, since we are tently started, has been increas- told that the atoms that make up all materials consist ingly fruitful in modern mostly of empty space. Here is a similar question that chemistry. But this activity has is put in a more sophisticated fashion. In modern certainly not replaced the kind of physics any body is described as a superposition of chemistry in which most practitioners are engaged. many wavefunctions, all of which stretch out to infin- Indeed, chemists far outnumber scientists in all other ity in principle. How is it then that the person I am fields of science. According to some indicators, such as talking to across my desk appears to be located in one the numbers of articles published per year, chemistry particular place? may even outnumber all the other fields of science put together. If there is any sense in which chemistry can The general answer to both such questions is that be said to have been reduced then it can equally be although the physics of microscopic objects essen- said to be in a high state of "oxidation" regarding cur- tially governs all of matter, one must also appeal to rent academic and industrial productivity. the laws of chemistry, material science, biology, and Starting in the early 1990s a group of philosophers other sciences. -

Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry

CALL FOR PAPERS First International Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019 University of Paris Diderot, France Extended Deadline for Abstract Submission: 28 February 2019 The aim of this conference is to bring philosophers of biology and philosophers of chemistry together and to explore common grounds and topics of interest. We particularly welcome papers on (1) the philosophy of interdisciplinary fields between biology and chemistry; (2) historical case studies on the disciplinary divergence and convergence of biology and chemistry; and (3) the similarities and differences between philosophical approaches to biology and chemistry. Philosophy is broadly construed and includes epistemological, methodological, ontological, metaphysical, ethical, political, and legal issues of science. For a detailed description of possible topics, please see below and visit the conference website http://www.sphere.univ-paris-diderot.fr/spip.php?article2228&lang=en Instructions for Abstract Submission Submit a Word file including author name(s), affiliation, paper title, and an abstract of maximum 500 words by 28 February 2019 to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) . Registration If you are interested in participating, please register by sending an e-mail to Jean-Pierre Llored ([email protected]) before 30 April 2019. Venue Room 454A, Building Condorcet, University Paris Diderot, 4, rue Elsa Morante, 75013 Paris, France Sponsors CNRS; Laboratory SPHERE, Laboratory LIED, and Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Paris Diderot; Fondation de la Maison de la Chimie; Free University of Brussels; University of Lille Organizers Cécilia Bognon, Quentin Hiernaux, Jean-Pierre Llored, Joachim Schummer First international Conference on Bridging the Philosophies of Biology and Chemistry 25-27 June 2019, University of Paris Diderot, France Description Background For much of the twentieth century, philosophy of science had almost exclusively been focused on physics and mathematics. -

Rethinking the Pragmatic Systems Biology and Systems-Theoretical Biology Divide: Toward a Complexity-Inspired Epistemology of Systems Biomedicine T

Medical Hypotheses 131 (2019) 109316 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Medical Hypotheses journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mehy Rethinking the pragmatic systems biology and systems-theoretical biology divide: Toward a complexity-inspired epistemology of systems biomedicine T Srdjan Kesić Department of Neurophysiology, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, University of Belgrade, Despot Stefan Blvd. 142, 11060 Belgrade, Serbia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This paper examines some methodological and epistemological issues underlying the ongoing “artificial” divide Systems biology between pragmatic-systems biology and systems-theoretical biology. The pragmatic systems view of biology has Cybernetics encountered problems and constraints on its explanatory power because pragmatic systems biologists still tend Second-order cybernetics to view systems as mere collections of parts, not as “emergent realities” produced by adaptive interactions Complexity between the constituting components. As such, they are incapable of characterizing the higher-level biological Complex biological systems phenomena adequately. The attempts of systems-theoretical biologists to explain these “emergent realities” Epistemology of complexity using mathematics also fail to produce satisfactory results. Given the increasing strategic importance of systems biology, both from theoretical and research perspectives, we suggest that additional epistemological and methodological insights into the possibility of further integration between -

Ld1 in PURSUIT of TRUTH

IN PURSUIT OF TRUTH Essays on the Philosophy of Karl Popper on the Occasion of His 80th Birthday Edited by PA UL LEVINSON \ with Fore words by (t 21). Isaac Asimov and Helmut Schmidt Chancellor, Federal Republic of Germany I1b2. f'.- t4 z;-Ld1 HUMANITIES PRESS INC. Atlantic Highlands, NJ 248 liv PURSUIT OP TROT/I hope and no proof is Stoicism and Judeo-Christian religion, in which irrationalism and stoicism alternate. Yet there is no inconsistency in the philosophy of hope without proof, especially as a moral injunction to oiler the benefit of doubt wherever at all possible. Now, the philosophy of hope without proof is not exactly Popper's. It began with T. H. Huxley, the famous militant Darwinian, and H. C. Wells. Its best expression is in Bertrand Russell's Free A Popperian Harvest0 Man's Worship," the manifesto of hope born out of despair, clinging to both despair and reason most heroically. This famous paper, published in Russell's W. W. BARTLEY, III Philosophical Essays of 1910, is a sleeper. It was hardly noticed by It is by its methods rather than its subject-matter that philosophy contemporaries and followers, yet now it is the expression of current religion, is to be distinguished from other arts or sciences. ofcurrent scientific ethos. Here, I think, Popper's philosophy of science gave it A. J. Ayer, 1955' substance. Philosophers arc as free as others to use any method in searching Or perhaps Russell's "Free Man's Worship" gives Popper's philosophy of truth. There is no tnethod peculiar to philosophy. -

Adaptationism and the Logic of Research Questions: How to Think Clearly About Evolutionary Causes

Biol Theory (2015) 10:343–362 DOI 10.1007/s13752-015-0214-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Adaptationism and the Logic of Research Questions: How to Think Clearly About Evolutionary Causes Elisabeth A. Lloyd1 Received: 20 March 2015 / Accepted: 29 May 2015 / Published online: 9 July 2015 Ó Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research 2015 Abstract This article discusses various dangers that popular methods, despite its benign reputation. In ‘‘The accompany the supposedly benign methods in behavioral Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm,’’ evolutionary biology and evolutionary psychology that fall Gould and Lewontin (1979) drew attention to several under the framework of ‘‘methodological adaptationism.’’ dangers in using this method. In this article, I present a A ‘‘Logic of Research Questions’’ is proposed that aids in framework for analysis that makes their worries clearer. I clarifying the reasoning problems that arise due to the also warn of further risks of this methodological frame- framework under critique. The live, and widely practiced, work, expanding on the dangers it poses to scientific rea- ‘‘evolutionary factors’’ framework is offered as the key soning in evolutionary biology. At the same time, I comparison and alternative. The article goes beyond the emphasize that I am not attacking the notion of looking for traditional critique of Stephen Jay Gould and Richard C. adaptations in evolutionary studies: I am not anti-adapta- Lewontin, to present problems such as the disappearance of tion. The issues concern which framework is most appro- evidence, the mishandling of the null hypothesis, and priate and fruitful. failures in scientific reasoning, exemplified by a case from As evolutionary biology is usually taught and con- human behavioral ecology. -

A New Defense of Adaptationism

Prepared for the Northwest Philosophy Conference, Fall 2002 A new defense of adaptationism Mark A. Bedau Reed College, 3203 SE Woodstock Blvd., Portland OR 97202 503-517-7337 http://www.reed.edu/~mab [email protected] Abstract The scientific legitimacy of adaptationist explanations has been challenged by Gould and Lewontin in “The Spandrals of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm.” The canonical response to this challenge is weak, because it concedes that the presupposition that an adaptationist explanation is needed cannot be tested empirically. This paper provides a new kind of defense of adaptationism by providing such a test. The test is described in general terms and then illustrated in the context of an artificial system—a simulation of self-replicating computer code mutating and competing for space in computer memory. It is a cliché to explain the giraffe’s long neck as an adaptation for browsing in tall tree. But the scientific legitimacy of such adaptive explanations is controversial, largely because of the classic paper “The Spandrals of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme” published by Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin in 1979. The controversy persists, I believe, in part because the fundamental challenge raised by Gould and Lewontin has not yet been met; in fact, it is rarely even acknowledged. This paper addresses this challenge and defends the scientific legitimacy of adaptive explanations in a new and deeper way. First, some terminology.1 I will refer to claims to the effect that a trait is an adaptation as an adaptive hypothesis. -

Adaptationism for Human Cognition: Strong, Spurious Or Weak? Scott Atran

Adaptationism for Human Cognition: Strong, Spurious or Weak? Scott Atran To cite this version: Scott Atran. Adaptationism for Human Cognition: Strong, Spurious or Weak?. Mind and Language, Wiley, 2005, 20 (1). ijn_00000574 HAL Id: ijn_00000574 https://jeannicod.ccsd.cnrs.fr/ijn_00000574 Submitted on 1 Feb 2005 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Adaptationism for Human Cognition: Strong, Spurious or Weak? SCOTT ATRAN Abstract: Strong adaptationists explore complex organic design as task-specific adapta- tions to ancestral environments. This strategy seems best when there is evidence of homology. Weak adaptationists don’t assume that complex organic (including cognitive and linguistic) functioning necessarily or primarily represents task-specific adaptation. This approach to cognition resembles physicists’ attempts to deductively explain the most facts with fewest hypotheses. For certain domain-specific competencies (folkbiol- ogy) strong adaptationism is useful but not necessary to research. With group-level belief systems (religion) strong adaptationism degenerates into spurious notions of social function and cultural selection. In other cases (language, especially universal grammar) weak adaptationism’s ‘minimalist’ approach seems productive. 1. Introduction In a sense, everyone who isn’t a creationist and who thinks that Darwin’s theory of natural selection isn’t moonshine is an adaptationist when it comes to explaining the origins of human cognition.