Overshadows Golden Asian Studies [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors

THE WORLD BANK GROUP Public Disclosure Authorized 2016 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS Public Disclosure Authorized SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS Public Disclosure Authorized Washington, D.C. October 7-9, 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK GROUP Headquarters 1818 H Street, NW Washington, D.C. 20433 U.S.A. Phone: (202) 473-1000 Fax: (202) 477-6391 Internet: www.worldbankgroup.org iii INTRODUCTORY NOTE The 2016 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group (Bank), which consist of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), held jointly with the International Monetary Fund (Fund), took place on October 7, 2016 in Washington, D.C. The Honorable Mauricio Cárdenas, Governor of the Bank and Fund for Colombia, served as the Chairman. In Committee Meetings and the Plenary Session, a joint session with the Board of Governors of the International Monetary Fund, the Board considered and took action on reports and recommendations submitted by the Executive Directors, and on matters raised during the Meeting. These proceedings outline the work of the 70th Annual Meeting and the final decisions taken by the Board of Governors. They record, in alphabetical order by member countries, the texts of statements by Governors and the resolutions and reports adopted by the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group. In addition, the Development Committee discussed the Forward Look – A Vision for the World Bank Group in 2030, and the Dynamic Formula – Report to Governors Annual Meetings 2016. -

Āirani Cook Islands Māori Language Week

Te ’Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki ’Āirani Cook Islands Māori Language Week Education Resource 2016 1 ’Akapapa’anga Manako | Contents Te 'Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki 'Āirani – Cook Islands Māori Language Week Theme 2016……………………………………………………….. 3 Te tangianga o te reo – Pronunciation tips …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Tuatua tauturu – Encouraging words …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Tuatua purapura – Everyday phrases……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 9 ’Anga’anga raverave no te ’Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki ’Āirani 2016 - Activity ideas for the Cook Islands Language Week 2016… 11 Tua e te au ’īmene – Stories and songs………………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………………… 22 Te au toa o te reo Māori Kūki ’Āirani – Cook Islands Māori Language Champions………………………………………………………………………….. 27 Acknowledgements: Teremoana MaUa-Hodges We wish to acknowledge and warmly thank Teremoana for her advice, support and knowledge in the development of this education resource. Te ’Epetoma o te reo Teremoana is a language and culture educator who lives in Māori Kūki ’Āirani Kūmiti Wellington Porirua City, Wellington. She hails from te vaka Takitumu ō Rarotonga, ‘Ukarau e ‘Ingatu o Atiu Enuamanu, and Ngāpuhi o Aotearoa. 2 Te 'Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki 'Āirani - Cook Islands Māori Language Week 2016 Kia āriki au i tōku tupuranga, ka ora uatu rai tōku reo To embrace my heritage, my language lives on Our theme for Cook Islands Māori Language Week in 2016 is influenced by discussions led by the Cook Islands Development Agency New Zealand (CIDANZ) with a group of Cook Islands māpū (young people). The māpū offered these key messages and helpful interpretations of te au tumu tāpura (the theme): NGUTU’ARE TANGATA │ FAMILY Embrace and celebrate ngutu’are tangata (family) and tapere (community) connections. -

O C E a N O C E a N C T I C P a C I F I C O C E a N a T L a N T I C O C E a N P a C I F I C N O R T H a T L a N T I C a T L

Nagurskoye Thule (Qanaq) Longyearbyen AR CTIC OCE AN Thule Air Base LAPTEV GR EENLA ND SEA EAST Resolute KARA BAFFIN BAY Dikson SIBERIAN BARENTS SEA SEA SEA Barrow SEA BEAUFORT Tiksi Prudhoe Bay Vardo Vadso Tromso Kirbey Mys Shmidta Tuktoyaktuk Narvik Murmansk Norilsk Ivalo Verkhoyansk Bodo Vorkuta Srednekolymsk Kiruna NORWEGIAN Urengoy Salekhard SEA Alaska Oulu ICELA Anadyr Fairbanks ND Arkhangelsk Pechora Cape Dorset Godthab Tura Kitchan Umea Severodvinsk Reykjavik Trondheim SW EDEN Vaasa Kuopio Yellowknife Alesund Lieksa FINLAND Plesetsk Torshavn R U S S Yakutsk BERING Anchorage Surgut I A NORWAY Podkamennaya Tungusk Whitehorse HUDSON Nurssarssuaq Bergen Turku Khanty-Mansiysk Apuka Helsinki Olekminsk Oslo Leningrad Magadan Yurya Churchill Tallin Stockholm Okhotsk SEA Juneau Kirkwall ESTONIA Perm Labrador Sea Goteborg Yedrovo Kostroma Kirov Verkhnaya Salda Aldan BAY UNITED KINGDOM Aluksne Yaroslavl Nizhniy Tagil Aberdeen Alborg Riga Ivanovo SEA Kalinin Izhevsk Sverdlovsk Itatka Yoshkar Ola Tyumen NORTH LATVIA Teykovo Gladkaya Edinburgh DENMARK Shadrinsk Tomsk Copenhagen Moscow Gorky Kazan OF BALTIC SEA Cheboksary Krasnoyarsk Bratsk Glasgow LITHUANIA Uzhur SEA Esbjerg Malmo Kaunas Smolensk Kaliningrad Kurgan Novosibirsk Kemerovo Belfast Vilnius Chelyabinsk OKHOTSK Kolobrzeg RUSSIA Ulyanovsk Omsk Douglas Tula Ufa C AN Leeds Minsk Kozelsk Ryazan AD A Gdansk Novokuznetsk Manchester Hamburg Tolyatti Magnitogorsk Magdagachi Dublin Groningen Penza Barnaul Shefeld Bremen POLAND Edmonton Liverpool BELARU S Goose Bay NORTH Norwich Assen Berlin -

FORTY-NINTH SESSION Hansard Report

FORTY-NINTH SESSION Hansard Report 49th Session Fourth Meeting Volume 4 WEDNESDAY 5 JUNE 2019 MR DEPUTY SPEAKER took the Chair at 9.00 a.m. OPENING PRAYER MR DEPUTY SPEAKER (T. TURA): Please be seated. Greetings to everyone this morning in the Name of the Lord. We say thank you to our Chaplain for the words of wisdom from God and let that be our guidance throughout the whole day. Kia Orana to everyone in this Honourable House this morning, Honourable Members of Parliament, the Clerk of Parliament and your staff, and our friend from WA, Australia – Peter McHugh. Those in the Public Gallery – greetings to you all and May the Lord continue to bless each and everyone here today. MR DEPUTY SPEAKER’S ANNOUNCEMENTS Honourable Members, I have good news for you all and for those interested in the Budget Book 1 and Budget Book 2. These are now available on the MFEM website under Treasury. These will also be available on the Parliament website today. Honourable Members, I have a very special Kia Orana and acknowledgment to four very special Cook Islanders today who received the Queen’s Birthday Honours. On behalf of the Speaker of this Honourable House, the Honourable Niki Rattle may I extend to them our warmest congratulations for their utmost achievements that we should all be proud of them today. Firstly, the businessman, Ewan Smith of Air Rarotonga. He received one of the highest New Zealand Honours. Congratulations Ewan. Secondly, to Mrs Rima David. She received the British Empire Medal. Congratulations Rima. Thirdly, to Iro Pae Puna. -

Foreign Diplomatic Offices in the United States

FOREIGN DIPLOMATIC OFFICES IN THE UNITED STATES AFGHANISTAN phone (212) 750–8064, fax 750–6630 ˜ Embassy of Afghanistan Her Excellency Elisenda Vives Balmana 2341 Wyoming Avenue, NW., Washington, DC Ambassador E. and P. 20008 Consular Office: California, La Jolla phone (202) 483–6410, fax 483–6488 ANGOLA His Excellency Hamdullah Mohib Ambassador E. and P. Embassy of the Republic of Angola Consular Offices: 2100–2108 16th Street, NW., Washington, DC 20009 California, Los Angeles phone (202) 785–1156, fax 785–1258 New York, New York His Excellency Agostinho Tavares da Silva Neto AFRICAN UNION Ambassador E. and P. Delegation of the African Union Mission Consular Offices: 1640 Wisconsin Avenue, NW., Washington, DC California, Los Angeles 20007 New York, New York Embassy of the African Union Texas, Houston phone (202) 342–1100, fax 342–1101 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA Her Excellency Arikana Chihombori Quao Embassy of Antigua and Barbuda Ambassador (Head of Delegation) 3216 New Mexico Avenue, NW., Washington, DC ALBANIA 20016 Embassy of the Republic of Albania phone (202) 362–5122, fax 362–5225 2100 S Street, NW., Washington, DC 20008 His Excellency Ronald Sanders phone (202) 223–4942, fax 628–7342 Ambassador E. and P. Her Excellency Floreta Faber Consular Offices: Ambassador E. and P. District of Columbia, Washington Consular Offices: Florida, Miami Connecticut, Greenwich New York, New York Georgia, Avondale Estates Puerto Rico, Guaynabo Louisiana, New Orleans ARGENTINA Massachusetts, Boston Embassy of the Argentine Republic Michigan, West Bloomfield -

DP192 Regional Programming in the 11Th European

European Centre for Development Policy Management Discussion Paper No. 192 June 2016 Prospects for supporting regional integration effectively An independent analysis of the European Union’s approach to the 11th European Development Fund regional programming by Alisa Herrero and Cecilia Gregersen www.ecdpm.org/dp192 ECDPM – LINKING POLICY AND PRACTICE IN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION ECDPM – ENTRE POLITIQUES ET PRATIQUE DANS LA COOPÉRATION INTERNATIONALE Prospects for supporting regional integration effectively An independent analysis of the European Union's approach to the 11th European Development Fund regional programming Alisa Herrero and Cecilia Gregersen June 2016 Key messages Regional integration is Learning from the past The EU adopted a To effectively support one of the was one of the key prescriptive and regional integration cornerstones of the drivers behind the normative in the future, the EC EU's development and EU’s new approach to programming systems, incentives international supporting regional approach, which and capacities cooperation policy and cooperation in the 11th excluded relevant guiding programming is an area where the European ACP actors need to be geared EU is seen as having a Development Fund throughout critical towards producing real added value and programming stages of the higher impact rather know-how in its process. Innovations process. This than higher cooperation with introduced were approach is difficult disbursement rates. African, Caribbean and mostly geared to to reconcile with the This will require, Pacific countries. addressing aid principles of among others, management ownership and co- ensuring that future problems, but it is management programming is unclear how and underpinning the informed by a more whether they will Cotonou Partnership sophisticated maximise impact on Agreement. -

Herald Issue 669 05 June 2013

PB REHAB WEEKLY ENTERTAINMENT SCHEDULE >>> Sunset BarBQs at the Shipwreck Hut Saturday Seafood menu with Jake Numanga on the Ukulele 6pm Tuesday Sunset BBQ with Garth Young on Piano 6pm Thursday Sunset Cocktails with Rudy Aquino 5.30pm-7.30pm Reservations required 22 166 Aroa Beachside Inn, Betela Great Food, Great Entertainment Cakes for all ocassions! Edgewater Cakes Enquiries call us on 25435 extn 7010 Always the best selection, best price & best service at Goldmine! Goldmine Model, Abigail is modelling a beautiful bracelet & a necklace from Goldmine. POWERBALL RESULTS Drawn: 30/5/13 Draw num: 889 PB REHAB FRIDAY NITES is Boogie Nite with DJ Ardy 10pm-2am. $4 House Spirits/Beers + FREE ENTRY B4 11pm. + FREE ENTRY 10pm-2am. $4 House Spirits/Beers Ardy with DJ is Boogie Nite NITES REHAB FRIDAY TATTSLOTTO RESULTS Drawn:1/6/13 Draw num: 3325 SUPP: OZLOTTO RESULTS Drawn: 04/6/13 Draw num: 1007 Next draw: REHAB WEDNESDAY NITES is WOW Nite with DJ Ardy 9pm-12am. Get in B4 10pm & go in the draw to win a $50 Bar Card. FREE ENTRY ALL NITE FREE ENTRY win a $50 Bar Card. to in the draw in B4 10pm & go 9pm-12am. Get Ardy with DJ Nite is WOW NITES REHAB WEDNESDAY SUPP: REHAB SATURDAY NITES is HAPPY HOUR MADNESS with DJ Junior. 2-4-1 Drinks + FREE ENTRY B4 10pm Cook islands Herald 05 June 2013 News 2 CIP Conference deferred, Leadership challenge averted Factions’ showdown on hold till 2014 By George Pitt team Heather and Bishop to An anticipated challenge boost sagging Party popularity to the Cook Islands Party heading into the next general leadership has been stalled elections. -

Countries and Their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by Spaceduck (Spaceduck) Via Cheatography.Com/4/Cs/56

Countries and their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by SpaceDuck (SpaceDuck) via cheatography.com/4/cs/56/ Countries and their Captial Cities Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Afghani stan Kabul Canada Ottawa Federated States of Palikir Albania Tirana Cape Verde Praia Micronesia Algeria Algiers Cayman Islands George Fiji Suva American Samoa Pago Pago Town Finland Helsinki Andorra Andorra la Vella Central African Republic Bangui France Paris Angola Luanda Chad N'Djamena French Polynesia Papeete Anguilla The Valley Chile Santiago Gabon Libreville Antigua and Barbuda St. John's Christmas Island Flying Fish Gambia Banjul Cove Argentina Buenos Aires Georgia Tbilisi Cocos (Keeling) Islands West Island Armenia Yerevan Germany Berlin Colombia Bogotá Aruba Oranjestad Ghana Accra Comoros Moroni Australia Canberra Gibraltar Gibraltar Cook Islands Avarua Austria Vienna Greece Athens Costa Rica San José Azerbaijan Baku Greenland Nuuk Côte d'Ivoire Yamous‐ Bahamas Nassau Grenada St. George's soukro Bahrain Manama Guam Hagåtña Croatia Zagreb Bangladesh Dhaka Guatemala Guatemala Cuba Havana City Barbados Bridgetown Cyprus Nicosia Guernsey St. Peter Port Belarus Minsk Czech Republic Prague Guinea Conakry Belgium Brussels Democratic Republic of the Kinshasa Guinea- Bissau Bissau Belize Belmopan Congo Guyana Georgetown Benin Porto-Novo Denmark Copenhagen Haiti Port-au -P‐ Bermuda Hamilton Djibouti Djibouti rince Bhutan Thimphu Dominica Roseau Honduras Tegucig alpa Bolivia Sucre Dominican Republic Santo -

CBD Third National Report

CONTENTS A. REPORTING PARTY ............................................................................................................... 3 Information on the preparation of the report ....................................................................... 3 B. PRIORITY SETTING, TARGETS AND OBSTACLES ....................................................................... 4 Priority Setting ................................................................................................................ 6 Challenges and Obstacles to Implementation ...................................................................... 7 2010 Target .................................................................................................................... 9 Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) ...................................................................37 Ecosystem Approach .......................................................................................................54 C. ARTICLES OF THE CONVENTION ...........................................................................................56 Article 5 – Cooperation ....................................................................................................56 Article 6 - General measures for conservation and sustainable use ........................................58 Biodiversity and Climate Change .................................................................................60 Article 7 - Identification and monitoring .............................................................................61 -

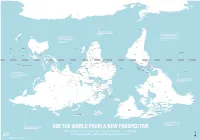

Is Map Is Just As Accurate As the One We're All Used To

ROSS SEA WEDDELL SEA AMUNDSEN SEA ANTARCTICA BELLINGSHAUSEN SEA AMERY ICE SHELF SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SOUTHERN OCEAN SCOTIA SEA DRAKE PASSAGE FALKLAND ISLANDS Stanley (U.K.) THE RATIO OF LAND TO WATER IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BY THE TIME EUROPEANS ADOPTED IS 1 TO 5 THE NORTH-POINTING COMPASS, PTOLEMY WAS A HELLENIC Wellington THEY WERE ALREADY EXPERIENCED NEW TASMAN SEA ZEALAND CARTOGRAPHER WHOSE WORK CHILE IN NAVIGATING WITH REFERENCE TO IN THE SECOND CENTURY A.D. ARGENTINA THE NORTH STAR Canberra Buenos Santiago GREAT AUSTRALIAN BIGHT POPULARIZED NORTH-UP Montevideo Aires SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN URUGUAY ORIENTATION SOUTH AFRICA Maseru LESOTHO SWAZILAND Mbabane Maputo Asunción AUSTRALIA Pretoria Gaborone NEW Windhoek PARAGUAY TONGA Nouméa CALEDONIA BOTSWANA Saint Denis NAMIBIA Nuku’Alofa (FRANCE) MAURITIUS Port Louis Antananarivo MOZAMBIQUE CHANNEL ZIMBABWE Suva Port Vila MADAGASCAR VANUATU MOZAMBIQUE Harare La Paz INDIAN OCEAN Brasília LAKE SOUTH PACIFIC OCEAN FIJI Lusaka TITICACA CORAL SEA GREAT GULF OF BARRIER CARPENTARIA Lilongwe ZAMBIA BOLIVIA FRENCH POLYNESIA Apia REEF LAKE (FRANCE) SAMOA TIMOR SEA COMOROS NYASA ANGOLA Lima Moroni MALAWI Honiara ARAFURA SEA BRAZIL TIMOR LESTE PERU Funafuti SOLOMON Port Dili Luanda ISLANDS Moresby LAKE Dodoma TANGANYIKA TUVALU PAPUA Jakarta SEYCHELLES TANZANIA NEW GUINEA Kinshasa Victoria BURUNDI Bujumbura DEMOCRATIC KIRIBATI Brazzaville Kigali REPUBLIC LAKE OF THE CONGO SÃO TOMÉ Nairobi RWANDA GABON ECUADOR EQUATOR INDONESIA VICTORIA REP. OF AND PRINCIPE KIRIBATI EQUATOR -

Issues and Events, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018

Polynesia in Review: Issues and Events, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 Reviews of American Sāmoa, Hawai‘i, inflow of people to the islands” (CIN, Sāmoa, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and 1 June 2017), so are able to anticipate Wallis and Futuna are not included in changes and demands for services and this issue. resources. However, eighteen months on, the official details of people’s Cook Islands mobility in and out of the country, This review covers the two-year period economic activity, housing, and well- from July 2016 to June 2018 and being are still not available. On the tracks a range of ongoing and emerg- face of it, it would seem that timely ing concerns. Featured here are the and informed public policymaking, implications from the 2016 population planning, and service provisions will census, Marae Moana (the national be impacted. But to some extent this marine park), the Cook Islands’ is not necessarily a bad thing, because impending Organisation for Economic population-related policies need to Co-operation and Development be informed by more than just demo- (oecd) graduation to high-income graphic trends, which invariably can country status, a controversial local be used to support the taken-for- tax amnesty, and events connected granted arguments typically associated with the 2018 general election. with the vulnerabilities and question- 2016 saw the five-year national able viability of small island state population survey get underway. development and economies (Baldac- Preliminary results of the 2016 cen- chino and Bertram 2009). sus, which was held on 1 December, Depopulation is a national concern recorded a total population of 17,459 and a political football (CIN, 31 May (mfem 2018c). -

17 13Oct2020 (221)

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Nauru Bulletin Issue 17-2020/221 13 October 2020 Presidents hail special MPS a success COVID-free Micronesia holds largest in-person meeting since the start of the pandemic he special meeting of the President Aingimea says the outcomes TMicronesian Presidents’ Summit is are positive as the meeting strengthens hailed a success by the five presidents of the bond of the Micronesian region in the regional group. coming together and underscores the The meeting held in the Republic of Palau progressive systems and strategies in from 1 to 3 October is in conjunction place to keep their countries safe from with Palau’s 26th Independence Day COVID. celebrations, in which President Lionel The meeting also solidifies the strong Aingimea and the Presidents of Kiribati, stance behind the groups’ preferred Marshall Islands and the Federated candidate for the position of secretary- States of Micronesia were extended an general of the Pacific Islands Forum invitation to attend. (PIF); a selection that is now contested Nauru and the Marshall Islands led high Presidents of the Micronesian countries at the opening by four other candidates. level delegations to attend both events, of the special MPS meeting in Palau, 30Sep As a result, the Micronesian leaders while the Presidents of Kiribati and FSM issued a strong statement where they attended virtually. will withdraw from the PIF if the President Aingimea says the in-person ‘gentleman’s agreement’ and the Pacific The meeting is the largest in-person meeting meeting demonstrates to the world the Way of rotating the position among the sub- of Pacific leaders to be held since the global region’s effective strategies in maintaining regions is not honoured and Micronesia is COVID-19 pandemic was declared by their COVID-free status and the respect and not allowed its turn for the SG post.