Responding to David Hirsh's Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primo Levi and the Material World

Gerry Kearns1 If wood were an element: Primo Levi and the material world Abstract The precarious survival of a single shed from the Jewish slave labour quarters of the industrial complex that was Auschwitz- Monowitz offers an opportunity to reflect upon aspects of the materiality of the signs of the Holocaust. This shed is very likely ne that Primo Levi knew and its survival incites us to interrogate its materiality and significance by engaging with Levi’s own writings on these matters. I begin by explicating the ways the shed might function as an ‘encountered sign,’ before moving to consider its materiality both as a product of modernist genocide and as witness to the relations between precarity and vitality. Finally, I turn to the texts written upon the shed itself and turn to the performative function of Nazi language. Keywords Holocaust, icon, index, materiality, performativity, Primo Levi Fig. 1 - The interior of the shed, December 2012 (Photograph by kind permission of Carlos Reijnen) It is December 2012, we are near the town of Monowice in Poland. Alongside a small farmhouse, there is a hay-shed. The shed is in two parts with two doorways communicating and above these, “Eingang” and “Ausgang”. In the further part of the shed, there is more text, in Gothic font, in German. Along a crossbeam 1 National University of Ireland, Maynooth; [email protected]. I want to thank the directors of the Terrorscapes Project (Rob van der Laarse and Georgi Verbeeck) for the invitation to come on the field trip to Auschwitz. I want to thank Hans Citroen and Robert Jan van Pelt for their patient teaching about the history of the site. -

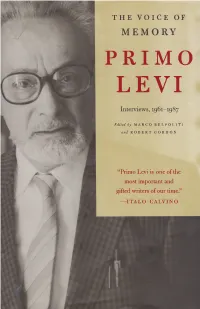

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

The Complete Works of Primo Levi Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE COMPLETE WORKS OF PRIMO LEVI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Primo Levi,Ann Goldstein,Toni Morrison | 3008 pages | 01 Oct 2015 | WW Norton & Co | 9780871404565 | English | United States The Complete Works of Primo Levi PDF Book Your question required. The two met in June, Levi was working on a bricklaying team, and Lorenzo was one of the chief masons. A Miscellany, confined to a private edition for decades, sheds further light on the prodigious Which included in this complete works. Or when Levi, who was fortunate enough to be chosen to work as a chemist, in the Buna laboratory, comes face to face with his chemistry examiner, Dr. He places in the gray zone all those who were morally compromised by some degree of collaboration with the Germans—from the lowliest those prisoners who got a little extra food by performing menial jobs like sweeping or being night watchmen through the more ambiguous the Kapos, often thuggish enforcers and guards who were themselves also prisoners to the utterly tragic the Sonderkommandos, Jews employed for a few months to run the gas chambers and crematoria, until they themselves were killed. At Auschwitz, Levi was imprisoned in a work camp that was supposed to produce a rubber called Buna, though none was actually manufactured. A Miscellany. The emphasis falls, for understandable reasons, on lament, on a liturgy of tears; or on immediate precision, on bringing concrete news, and on the attempt at comprehension. Community Reviews. Somehow he managed to do it almost dispassionately, with the rigor of his scientific mind, the better to take an accurate measure of the scope and scale of this crime against all of humanity in If This Is A Man. -

Primo Levi Vs. Dmitri Mendeleev

Primo Levi vs. Dmitri Mendeleev by Elena Ghibaudi philosophical conceptions. Levi, as a chemist in a fac- tory, gives to chemistry the credit of shaping his way of comparison between the figures of Levi and living: “I had grown up inside it, I had been educated in Mendeleev is proposed, based on their pecu- it, it had shaped my way of living and of looking at the Aliar ways of conceiving their professional role world—maybe even my language” [1]. of chemist, their life experiences, their achievements Mendeleev’s attitude is well described by his pu- and their thought. pil, V. E. Grum-Grzhimailo: “He imparted on his pupils his skill in observing and thinking, which no one book The Weltanschauung of these two fi gures, despite can give [..] When Mendeleev taught to think chemi- their having lived in distinct historical periods and their cally, he not only did his job and not only the job of the belonging to distinct cultures, was deeply infl uenced whole cycle of chemical sciences, but also the job of by the fact of being chemists: chemistry was - for both the whole natural faculty” [2].1 of them—a tool for interpreting the world around them The expression ‘To think chemically’ discloses a and acting eff ectively in it. The chemistry Levi talks peculiar epistemic attitude: the habit of conciliating about in his writings is not just a narrative pretext: it distinct levels of reality (macroscopic, microscopic is part of his vision of the world and a means of sur- and symbolic), i.e. -

Zona Grigia” the Paradox of Judgment in Primo Levi’S “Grey Zone”

CHAPTER 1 LA “ZONA GRIGIA” THE PARADOX OF JUDGMENT IN PRIMO LEVI’S “GREY ZONE” R Having measured up the meanders of the gray zone and pushed to explore the darkest side of Auschwitz, not only for judging but mainly for understanding the true nature of humans and their limits, is one of the most inestimable contributions made by Levi to any future moral philosophy. —Massimo Giuliani, Centaur in Auschwitz: Refl ections on Primo Levi’s Thinking Considerable attention has been paid by a number of scholars to Levi’s controversial notion of the “grey zone.” The concept proved fun- damental to his understanding of his Auschwitz experiences and has since been appropriated, often uncritically, in the fi elds of Holocaust studies, philosophy, law, history, theology, feminism, popular culture, and human rights issues relating to the Abu Ghraib prison scandal.1 In spite of this, there has been no attempt to provide a comprehensive analysis of the infl uences on the concept and its evolution, and little has been written on Levi’s moral judgments of “privileged” Jews. Recent in- terpretations and appropriations of the grey zone often misunderstand, expand upon, or intentionally depart from Levi’s ideas. This chapter returns to Levi’s original concept in order to investigate how he judges This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. Not for resale. La “Zona Grigia” 43 the “privileged” Jews he portrays, namely Kapos, Sonderkommandos, and Chaim Rumkowski of the Lodz Ghetto. The analysis reveals that even Levi himself could not abstain from judging those he argues should not be judged. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 26 March 2013 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Gregson, N. (2009) 'Material, literary narrative and cultural economy.', Journal of cultural economy., 2 (3). pp. 285-300. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17530350903345520 Publisher's copyright statement: This is an electronic version of an article published in Gregson, N. (2009) 'Material, literary narrative and cultural economy.', Journal of cultural economy., 2 (3). pp. 285-300. Journal of cultural economy is available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/openurl?genre=articleissn=1753-0350volume=2issue=3spage=285 Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk NG January 2009 Material, literary narrative and cultural economy: Primo Levi and the industrial short story Nicky Gregson: Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN [email protected] - 1 - NG January 2009 Abstract In this paper I argue that thinking about the material in cultural economy has much to gain from culture itself. -

Printed Matter

Centro Primo Levi New York September 24, 2016 Printed_Matter Special issue for the Library of Congress National Book Festival Archives The publication of Primo Levi’s Complete Works welcomes readers to a maze of different worlds, cultures, and historical references. Italy and Italian history, Piedmont and Piedmontese Jewry, science, literature, language and fascism as a ideology and a form of social interaction and individual response. Below is a list of archives and research for those who want to learn more about Primo Levi’s worlds. Primo Levi. A Chronology. Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi’s biography and selection of quotes by Ernesto Ferrero. Primo Levi Primo Levi’s life span, Turin 1919-Turin 1987, extended from the Centro di Documentazione end of World War I, to the years leading to the fall of the Berlin Ebraica Contemporanea Wall. Istituto Piermontese per la Storia della Resistenza/ All of his formative experiences — growing up in Fascist Italy Archivio Serafino within a middle class, liberal Jewish family, the ignominy of the Racial Laws, participating to the Resistance, his study of Polo del Novecento Torino chemistry, his love for the Classics and mountaineering, his arrest Archivi Ebraici del Piemonte and deportation to Auschwitz, his writing, — contributed to Archivio Ebraico Terracini distill one of the most acute, intransigent and far reaching reflections on the human condition. Fondazione Fossoli As a scientist, witness, writer of memoirs, fiction, poetry and Archivio Franco Antonicelli essays and as a public intellectual, Levi’s attention was focused The Shoah in Italy on the relationship between the powerful and the powerless and Primo Levi at the National Book Festival Edited by Alessandro Cassin and Natalia Indrimi !1 Centro Primo Levi New York September 24, 2016 on the corruptibility of the individual and collective moral fiber. -

Auschwitz As University: Primo Levi's Poetry and Fiction Post-Deportation

Auschwitz as University: Primo Levi’s Poetry and Fiction Post-Deportation and Return Auschwitz como universidad: La poesía y la ficción posdeportación y el regreso de Primo Levi Cheryl Chaffin Cabrillo College (CA) [email protected] I have to observe that really my deepest and most lasting loves are the least explicable.1 Resumen Primo Levi señaló que su experiencia de un año de duración, desde su deportación en febrero de 1944 hasta su liberación de Auschwitz en enero de 1945, fue el motivo principal de su necesidad de escribir. Levi llegó a decir que su experiencia en el campo de trabajo había sido una especie de universidad para él. Más allá de sus narrativas autobiográficas sobre los campos, principalmente en Si esto es un hombre (Se questo è un uomo) y La tregua, Levi escribió dos novelas, varios cuentos, poemas y ensayos. Estos trabajos demuestran el alcance de lo que el escritor exploró mientras ponía por escrito su relación con el mundo y con la naturaleza humana tras su liberación de Auschwitz. En este artículo, tengo en cuenta qué conocimiento extrajo Levi de los campos, algo que desarrolló durante las cuatro décadas restantes de su vida, al igual que cómo esas apreciaciones se reflejaron en su escritura. En concreto, este análisis se centra en las relaciones en la obra de Levi –entre la gente y en la respuesta de uno mismo frente al mundo– y su conocimiento y observación relativa a la intimidad y al conflicto durante y después de la guerra. 1 From Primo Levi’s 1981 book, The Search for Roots. -

Reflections on the Ethics of Technical and Literary Language in Primo Levi

Visions for Sustainability 2: 36-48, 2014 ORIGINAL PAPER DOI: 10.7401/visions.02.04 Reflections on the Ethics of Technical and Literary Language in Primo Levi Patrizia Piredda Independent scholar Abstract. In this article I will analyse the two modalities of writing which characterised Levi’s life, namely the technical writing of weekly professional reports, and the literary writing of poetry and short stories. I will above all focus on such texts as The Wrench, The Periodic Table, Other People’s Trades and the Essays and I will analyse the way in which chemistry lies at the basis of his poetic. The most significant difference between the above-mentioned forms of writing rests in the fact that Levi’s technical writing always describes reality on the basis of models created by sciences. Literary writing, on the other hand, does not reproduce a model nor describes a fixed order, because it functions as a way of representing the possibilities that lie beyond existence, i.e. it is a way of creating an order; literary writing does not restrict itself to describing an object, but instead produces new interpretations of the object, and consequently new interpretations of life. Therefore, I will analyse the function of metaphor because, from Levi’s perspective, it is necessary for good literature: in fact, thanks to its structure, metaphor is apt to show what cannot be described in a rigorous way, namely ethics and aesthetics. Keywords: Primo Levi, metaphor, scientific and literary language ISSN 2384-8677 DOI: 10.7401/visions.02.04 Article history: Accepted in revised form November, 06, 2014 Published online: November, 22, 2014 http://www.iris-sostenibilita.net/iris/vfs/vfsissues/article.asp?idcontributo=72 Citation: Piredda, P.