Bezaly Ashkenazy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

Benjamin Grosvenor, Piano

BENJAMIN GROSVENOR, PIANO a formidable technician and a thoughtful, coolly assured interpreter - Allan Kozinn, New York Times, ...a skill and talent not heard since Kissins teenage Russian debut - Bryce Morrison, Gramophone Magazine British pianist Benjamin Grosvenor is internationally recognized for his electrifying performances and penetrating interpretations. An exquisite technique and ingenious flair for tonal colour are the hallmarks which make Benjamin Grosvenor one of the most sought-after young pianists in the world. His virtuosic command over the most strenuous technical complexities never compromises the formidable depth and intelligence of his interpretations. Described by some as a Golden Age pianist (American Record Guide) and one almost from another age (The Times), Benjamin is renowned for his distinctive sound, described as poetic and gently ironic, brilliant yet clear-minded, intelligent but not without humour, all translated through a beautifully clear and singing touch (The Independent). Benjamin first came to prominence as the outstanding winner of the Keyboard Final of the 2004 BBC Young Musician Competition at the age of eleven. Since then, he has become an internationally regarded pianist performing with orchestras including the London Philharmonic, RAI Torino, New York Philharmonic, Philharmonia, Tokyo Symphony, and in venues such as the Royal Festival Hall, Barbican Centre, Singapores Victoria Hall, The Frick Collection and Carnegie Hall (at the age of thirteen). Benjamin has worked with numerous esteemed conductors including Vladimir Ashkenazy, Jií Blohlávek, Semyon Bychkov and Vladimir Jurowski. At just nineteen, Benjamin performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra on the First Night of the 2011 BBC Proms to a sold-out Royal Albert Hall. -

Monday, June 30Th at 7:30 P.M. Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Free Admission

JUNE 2008 Listener BLUE LAKE PUBLIC RADIO PROGRAM GUIDE Monday, June 30th at 7:30 p.m. TheBlue Grand Lake Rapids Fine ArtsSymphony’s Camp DavidFree LockingtonAdmission WBLV-FM 90.3 - MUSKEGON & THE LAKESHORE WBLU-FM 88.9 - GRAND RAPIDS A Service of Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp 231-894-5656 http://www.bluelake.org J U N E 2 0 0 8 H i g h l i g h t s “Listener” Volume XXVI, No.6 “Listener” is published monthly by Blue Lake Public Radio, Route Two, Twin Lake, MI 49457. (231)894-5656. Summer at Blue Lake WBLV, FM-90.3, and WBLU, FM-88.9, are owned and Summer is here and with it a terrific live from operated by Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp Blue Lake and broadcast from the Rosenberg- season of performances at Blue Lake Fine Clark Broadcast Center on Blue Lake’s Arts Camp. Highlighting this summer’s Muskegon County Campus. WBLV and WBLU are public, non-commercial concerts is a presentation of Beethoven’s stations. Symphony No. 9, the Choral Symphony, Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp with the Blue Lake Festival Orchestra, admits students of any race, color, Festival Choir, Domkantorei St. Martin from national or ethnic origin and does not discriminate in the administration of its Mainz, Germany, and soloists, conducted programs. by Professor Mathias Breitschaft. The U.S. BLUE LAKE FINE ARTS CAMP Army Field Band and Soldier’s Chorus BOARD OF TRUSTEES will present a free concert on June 30th, and Jefferson Baum, Grand Haven A series of five live jazz performances John Cooper, E. -

IIJ and the NHK Symphony Orchestra to Stream Hi-Res Audio Performances

For Immediate Release IIJ and the NHK Symphony Orchestra to Stream Hi-Res Audio Performances --This technological partnership is the first hi-res streaming of NHKSO concerts, confirming the feasibility of regular streaming services-- TOKYO—April 28, 2017—Internet Initiative Japan Inc. (IIJ, NASDAQ: IIJI, TSE1: 3774), one of Japan's leading Internet access and comprehensive network solutions providers, and the NHK Symphony Orchestra, Tokyo, (NHKSO) today announced that they are making hi-res recordings of the public performances of “The Meidensha 120th Anniversary | NHKSO Afternoon Classic Series” that are being held in April, May, and June 2017. They will then make these recordings available for on-demand streaming starting on May 19, 2017. This is the first time that performances of the NHKSO—a prominent orchestra in Japan—will be streamed in hi-res audio. IIJ will record three matinee performances at the Muza Kawasaki Symphony Hall in hi-res audio, using DSD 5.6 MHz (*1) and PCM 96 kHz / 24 bit (*2) formats. These recordings will be available for free and on demand as programs on IIJ's hi-res streaming service, PrimeSeat (*3). At the same time, IIJ will stream on-demand videos of the concerts for multiple devices, including PCs and smartphones. High-resolution audio formats—including the popular DSD and PCM systems—faithfully reproduce analog sound without compression, allowing listeners to enjoy the immersive, high-quality acoustic experience of a concert hall right in their homes. After evaluating this project's technological partnership for hi-res audio streaming, IIJ and the NHKSO will consider expanding the number of concerts they stream, to deliver even more NHKSO performances in high-quality audio to customers living room. -

Vladimir Ashkenazy Conductor/Piano

Vladimir Ashkenazy Conductor/Piano One of the few artists to combine a successful career as a pianist and conductor, Russian-born Vladimir Ashkenazy inherited his musical gift from both sides of his family; his father David Ashkenazy was a professional light music pianist and his mother Evstolia (née Plotnova) was daughter of a chorus master in the Russian Orthodox church. Ashkenazy first came to prominence on the world stage in the 1955 Chopin Competition in Warsaw and as first prize-winner of the Queen Elisabeth Competition in Brussels in 1956. Since then he has built an extraordinary career, not only as one of the most outstanding pianists of the 20th century, but as an artist whose creative life encompasses a vast range of activities and continues to offer inspiration to music-lovers across the world. Conducting has formed the larger part of Ashkenazy’s activities for more than 35 years. He continues his longstanding relationship with the Philharmonia Orchestra, who appointed him Conductor Laureate in 2000. In addition to his performances with the orchestra in London and around the UK each season, Vladimir Ashkenazy joins the Philharmonia Orchestra on countless tours worldwide. In the past, Ashkenazy and the Philharmonia have developed landmark projects such as Voices of Revolution: Russia 1917, Prokofiev and Shostakovich Under Stalin (a project which he also took to Cologne, New York, Vienna and Moscow) and Rachmaninoff Revisited (which was also presented in Paris). This summer, Vladimir Ashkenazy was named as the very first Conductor Laureate of Sydney Symphony Orchestra. This appointment has been made in recognition of his 50 year association with the Orchestra which began in 1969 and is an honour never before bestowed on any previous Sydney Symphony conductor. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

March 16, 2018: (Full-Page Version) Close Window

March 16, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window Spring Pledge Drive Begins! Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Violin Concerto in A minor, Op. 3 No. 6 I Musici Philips 412 128 02894121282 Awake! 00:11 Buy Now! Elgar Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 Barton Pine/BBC Symphony/Litton Avie 2375 822252237528 01:03 Buy Now! Schubert Impromptu in B flat, D. 935 No. 3 Alfred Brendel Philips 456 727 028945672724 L'amour est un oiseau rebelle (Habanera) ~ Berganza/Ambrosian Singers/London Symphony 01:16 Buy Now! Bizet DG 479 3590 028947935902 Carmen Orchestra/Abbado 01:22 Buy Now! Stanford Symphony No. 6 in E flat Ulster Orchestra/Handley Chandos 8627 5014682862721 01:59 Buy Now! Fauré Prelude ~ Penelope BBC Philharmonic/Tortelier Chandos 9416 9511594162 02:08 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 15 in D, Op. 28 "Pastoral" John O’Conor Telarc 80185 089408018527 02:33 Buy Now! Chadwick String Quartet No. 2 Portland String Quartet Northeastern 236 N/A 03:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Cello Concerto in D minor, RV 406 Rostropovich/Saint Paul CO/Wolff Teldec 77311 D 101707 03:12 Buy Now! Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Ax/Philharmonia Orchestra/Salonen Sony 53 289 07464532892 03:34 Buy Now! Brahms Serenade No. 2 in A, Op. 16 London Philharmonic/Boult EMI 65229 094636522920 Theme and Variations on Red River Valley for 04:01 Buy Now! Amram Ferguson/Colorado Symphony/Amram Newport Classic 85692 032466569227 Flute and Strings 04:16 Buy Now! Haydn Piano Sonata No. -

The Uuiversitj Musical Society

The UuiversitJ Musical Society The Uni~ersity of Michigan Presents Mstislav Rostropovich Cellist SAMUEL SANDERS, Pianist SUNDAY AFTERNOON, JANUARY 19, 1975, AT 2:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN PROGRAM Adagio BACH Adagio and Allegro SCHUMANN Sonata in F major, No.2, Op. 99 BRAHMS Allegro vivace Adagio affettuoso Allegro passionato Allegro molto INTERMISSION Three Meditations, from Mass LEONARD BERNSTEIN Dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich Sonata in D minor, Op. 40 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Moderato Moderato con moto Largo Allegretto M elodiya/ Angel, London, M onitol', Deutsche Grammophon R ecords Special Concert Complete Programs 3923 COMING EVENTS SYNTAGMA MUSICUM FROM AMSTERDAM Thursday, January 23 TOKYO STRING QUARTET Sunday, February 2 Haydn: Quartet, Op. 50, No.1; Bartok: Quartet No.5; Debussy : Quartet in G minor AMERICAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Sunday, February 9 MORTON GOULD, conductor Bernstein: "Candide" Overture; Strauss: "Macbeth"; Ives: Second Orchestral Set; Gould: Declaration Suite; Mussorgsky-Ravel: Pictures at an Exhihition PRAGUE CHAMBER ORCHESTRA (replacing Moscow Chamber Orchestra) Tuesday, February 11 Mozart: Symphony in D major, K. 504 ("Prague"); Prokofieff: "Classical Symphony" in D major; Dvorak: Czech Suite in D major, Op. 39 GOLDOVSKY GRAND OPERA THEATER Thursday, February 13 Donizetti: "The Interrupted Wedding Night"; Debussy : "The Prodigal Son" JEAN-PIERRE RAMPAL, Flutist, AND ROBERT VEYRON-LA CROIX, Keyboard . Tuesday, February 18 HARKNESS BALLET Thursday, February 20 CHHAU, MASKED DANCE OF BENGAL Saturday, -

Mise En Page 1

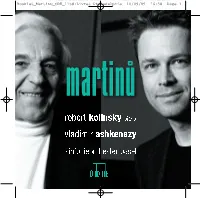

Cover and back cover: YELLOW MAGENTA CYAN BLACK Booklet_Martinu_ODE_1158:Livret Philadelphia 10/09/09 16:38 Page 1 marti n˚u robert kolinsky , piano vladimir ashkIesnmaozy Eskelinen sinfonieorchester basel Booklet_Martinu_ODE_1158:Livret Philadelphia 10/09/09 16:38 Page 2 Bohuslav Martin u˚ in Paris (1932) Booklet_Martinu_ODE_1158:Livret Philadelphia 10/09/09 16:38 Page 3 BOHUSLAV MARTI NU˚ (1890–1959) 1 Overture , H. 345 (1953) 6’30 Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 2 , H. 237 (1934) 21’13 2 I. Allegro moderato 8’22 3 II. Poco andante 6’31 4 III. Poco allegro 6’21 Les Fresques de Piero della Francesca , H. 352 (1955) 19’05 5 I. Andante poco moderato 7’40 6 II. Adagio 6’06 7 III. Poco allegro 5’19 Concerto for piano and Orchestra No. 4 “Incantation” , H. 358 (1956) 18’33 8 I. Poco allegro 8’56 9 II. Poco moderato 9’37 3 [65’54] ROBERT KOLINSKY , piano (2–4, 8–9) Sinfonieorchester Basel VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY Produced in association with Internationale Musikfesttage B. Martin u˚, Basel Publishers: Éditions Max Eschig (Overture), Panton International (Piano Concerto No. 2), Universal Edition (Les Fresques), Edition Bärenreiter (Piano Concerto No. 4) Recordings: Musiksaal Stadtcasino Basel, 29 & 30 October 2005 (live; 1–7) & 23 January 2007 (8–9) Executive Producer: Reijo Kiilunen Recording Producer: Andreas Werner Recording Engineer: Jakob Händel Digital Mastering: Enno Mäemets Piano Technician: Heinz Becker P 2009 Ondine Inc., Helsinki © 2009 Ondine Inc., Helsinki Booklet Editor: Jean-Christophe Hausmann Cover Photo: Alberto Venzago (Vladimir Ashkenazy, Robert Kolinsky) Photos of Bohuslav Martin u˚ reproduced with the kind permission of the Bohuslav Martin u˚ Centre/ Poli cˇka Cover Design and Booklet Layout: Eduardo Nestor Gomez Booklet_Martinu_ODE_1158:Livret Philadelphia 10/09/09 16:38 Page 4 n November 1953, within just five days, Bohuslav Martin u˚ (1890 Poli cˇka, Bohemia – 1959 Liestal, Switzerland) composed the Overture H. -

Lynn Freeman Olson Collection Cassette

LYNN FREEMAN OLSON COLLECTION CASSETTE RECORDINGS LIST Beethoven 9 Symphonien Ouverturen (6 tape boxed set)- Karajan Berliner Philharmonikar Vivaldi: Two Concertos for Two Violins / Two Sonatas for Two Violins and Continuo - Aston Magna Vivaldi: Concerti E Sinfonie - I Solisti Veneti/Claudio Scimone Mahler: Symphony No. 10 - Philadelphia Orchestra / James Levine (2 cassettes) Mahler: Symphony So, 1 - London Philharmonic - Klaus Tennstedt Debussy: 3 Nocturnes Ravel: Pavane & Bolero - Moscow Radio Large Symphony Orchestra / Yevgeni Svetlanov Debussy: La Mer, Nocturnes - Cleveland Orchestra/ Lorin Maazel Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 2 - Royal Philharmonic Orchestra / Yuri Temirkanov Rachmaninoff: Symphony Mo. 3 Shostakovich: Symphony No. 6 - London Symphony Orchestra / Andre Previn Rachmaninoff: Second Piano Concerto - Balakirev Islamey, Julius Katchen - London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Georg Solti Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 3 - Vladimir Ashkenazy - The London Symphony / Anatola Fistoulari Rachmaninoff: Piano Concertos 2 & 4 -Vladimir Ashkenazy - Concertgebouw Orchestra / Bernard Haitink Shostakovich: Symphony No. 11 ("1905") - Houston Symphony Orchestra / Leopold Stokowski Shostakovich: Symphony No. 6 / The Age of Gold (Ballet Suite) - Chicago Symphony / Leopold Stokowski Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7 ("Leningrad") - Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra / Paavo Berglund Shostakovich: Symphony No. 10 e minor Op, 93 - Austrian Broadcast Symphony Orchestra / Milan Horvat (2 cassette set) LYNN FREEMAN OLSON REFERENCE COLLECTION OF RECORDED SOUND -

( 1904- 1E87) Concerto No.2 for Cello and Orchestra, Op.77 Siao

BIS-CD-719 STEREO F p pl Total playing timez 65'27 KABALEVSKY. Dmitri (1904- 1e87) Concerto No.2 for Cello and Orchestra, Op.77 siao,"ait 27'13 E L Molto sostenuto - AIIegro molto e energico - Tbmpo I - attaccq 10'07 :l I Cadenza I (Tempo I Rubato - Allegro molto agitato 1 attacca r'44 E IL Poco marcato - attacca '',34 E] Cadenza II (L'istesso tempo - Molto sostenuto) - atto""o 2',36 - E lII. Andante con moto Allegro agitato - Molto tranquillo llJ KIIACIIATURIAN, Aram (1903- 1978) Concerto in E minor for Cello and Orchestra (1946) rsihorski)31'10 @ l. Attegro moclerato 1 /t1- A IL Andante sostenuto aL'acca 7',50 @ rrr.Atlegro 8'56 RACHMANINOV, Sergei (1828-1948) El Vocalise, Op.34 No. 14 enter'ationatMusicco.,Neayork) 8,57 (transcribed for cello and piano by Leonard Rose) Lentamente - Molto cantabile Mats Lidstriim, cello tr'tr Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra (leader: Christer Thorvaldsson) Vladimir Ashkenazy, Ei-E conductor/ E piano INSTRUMENTARIUM MatsLidstriim Cello;GiovanniGrancino(1712)ota generous loan from J.&A. Beale Ltd., London Vladimir Ashkenazy Grand Piano: Steinway. Piano technician: Bengt Eriksson Jt-is actually rather unfair that the art of playing the cello in the secondhalf of the I twentieth c_enturyhas been focused to such an extraordinary extent upon a rsingle person: Mstislav Rostropovich.In the light of his artistry it is easy ro forget that there have been other cellists of the highest international standard. some of these, like Rostropovich,came from the soviet union. The political situation during much of the period, however, prevented artists from the former Tsarist empire from enjoying a normal international career. -

825646079070.Pdf

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN 1770–1827 Violin Concerto in D major, Op.61 1 I Allegro ma non troppo 24.20 (Cadenza: Kreisler) 2 II Larghetto 9.01 3 III Rondo: Allegro 10.05 (Cadenza: Kreisler) 43.53 ITZHAK PERLMAN violin Philharmonia Orchestra/Carlo Maria Giulini 2 Itzhak Perlman Photo: © Christian Steiner 3 Beethoven: violin ConCerto A cornerstone of the repertoire, Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D major, Op.61 is, as far as performers are concerned, the most perfect work of its genre. Neither showy nor demonstrative, it seeks instead to express the noblest aspirations of the human soul. It’s the ideal blueprint, a model of majesty, serenity and grandeur, its beauty never-ending. It’s also the most tranquil and poetic of all violin concertos. The slightest lapse in taste would disfigure it, the slightest hint of ostentation would be an insult. There’s nowhere for a soloist to hide: this is a work that reveals your true nature. If you manage to convey its full nobility, you join the gods on Mount Olympus; if you succeed in making a memorable recording of it, your immortality is more or less guaranteed. Itzhak Perlman is among the very select number to have achieved both. He didn’t rush into recording the noblest works in the repertoire — this concerto and Bach’s Solo Sonatas and Partitas (see volume 41) — being wise enough to wait until he had reached full maturity, in terms of both his intellect and his technical mastery of the instrument. He has recorded the Beethoven twice, and both versions are among the greatest ever set down on disc.