Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Catholic Mission Handbook 2006

U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION HANDBOOK 2006 Mission Inventory 2004 – 2005 Tables, Charts and Graphs Resources ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Published by the U.S. CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION 3029 Fourth St., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202 – 884 – 9764 Fax: 202 – 884 – 9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org Additional copies may be ordered from USCMA. USCMA 3029 Fourth Street., NE Washington, DC 20017-1102 Phone: 202-884-9764 Fax: 202-884-9776 E-Mail: [email protected] Web Sites: www.uscatholicmission.org and www.mission-education.org COST: $4.00 per copy domestic $6.00 per copy overseas All payments should be prepaid in U.S. dollars. Copyright © 2006 by the United States Catholic Mission Association, 3029 Fourth St, NE, Washington, DC 20017-1102. 202-884-9764. [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE UNITED STATES CATHOLIC MISSION ASSOCIATION (USCMA)Purpose, Goals, Activities .................................................................................iv Board of Directors, USCMA Staff................................................................................................... v Past Presidents, Past Executive Directors, History ..........................................................................vi Part II: The U.S. -

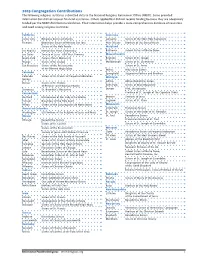

2018 Congregation Contributions the Following Religious Institutes Submitted Data to the National Religious Retirement Office (NRRO)

2018 Congregation Contributions The following religious institutes submitted data to the National Religious Retirement Office (NRRO). Some provided information but did not request financial assistance. Others applied but did not receive funding, as they are adequately funded per the NRRO distribution calculation. Their information helps provide a more comprehensive database of resources and need among religious institutes. California Louisiana Culver City Religious Sisters of Charity Lafayette Sisters of the Most Holy Sacrament Fremont Dominican Sisters of Mission San Jose New Orleans Brothers of the Sacred Heart of New England, Inc. Sisters of the Holy Family St. Benedict Benedictine Monks Los Angeles Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet Maine Orange Sisters of St. Joseph Biddeford Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary San Francisco Sisters of the Presentation Winslow Sisters of St. Joseph of the Blessed Virgin Mary Maryland San Rafael Sisters of St. Dominic Baltimore School Sisters of Notre Dame Colorado Xaverian Brothers USA Inc. Colorado Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration Towson Society of Jesus—Maryland Province Springs Massachusetts Denver Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity Lowell Sisters of Charity of Ottawa Connecticut Marlborough Sisters of St. Anne Hartford Missionaries of Our Lady of La Salette Milton Holy Union Sisters Putnam Daughters of the Holy Spirit Waltham Stigmatine Fathers and Brothers Wilton Sisters of the Congregation de Notre Dame Wrentham Sisters of St. Chretienne Delaware Michigan Middletown Canons Regular of Premontre Adrian Adrian Dominican Sisters District of Columbia Allen Park Sisters of Mary Reparatrix Washington Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur Detroit PIME Missionaries US Province of the Religious of Jesus and Mary Monroe Servants of Jesus Saginaw Sisters of St. -

"Altius Moderamen"

"Altius moderamen" It is a Latin term used in Canon 303 to mean that the friars of the First Order and Third Order Regular are to guarantee the fidelity of the SFO to the Franciscan charism, communion with the Church and union with the Franciscan Family, values which represent a vital commitment for the Secular Franciscans. ( General Constitutions of the Secular Franciscan Order , Article #85.2) First Order: Order of Friars Minor O.F.M. Order of Friars Minor, Capuchin O.F.M. Cap. Order of Friars Minor, Conventual O.F.M. Conv. Third Order Regular Friars T.O.R. ______________________________________________________________________________ THE CATHOLIC FRANCISCAN FAMILY First Order: Order of Friars Minor O.F.M. Order of Friars Minor, Capuchin O.F.M. Cap. Order of Friars Minor, Conventual O.F.M. Conv. Second Order: Poor Clares O.S.C.; P.C. Third Order: Secular Franciscan Order S.F.O. Third Order Regular T.O.R. ______________________________________________________________________________ There are several hundred Congregations of Religious Women and Men who also follow the Third Order Regular Rule. Many serve the SFO as Spiritual Assistants, but do not exercise the "altius moderamen" of the First Order and Third Order Regular friars. These congregations use a variety of initials, such as the following: Brothers of the Poor of St. Francis C.F.P. Congregation of the Sisters of St. Elizabeth of the Third Order Regular of St. Francis O.S.E. Congregation of the Sisters of St. Felix (Felician Sisters) C.S.S.F. Franciscan Brothers of Peace F.B.P. Version 1.0 St. -

2019 Congregation Contributions the Following Religious Institutes Submitted Data to the National Religious Retirement Office (NRRO)

2019 Congregation Contributions The following religious institutes submitted data to the National Religious Retirement Office (NRRO). Some provided information but did not request financial assistance. Others applied but did not receive funding because they are adequately funded per the NRRO distribution calculation. Their information helps provide a more comprehensive database of resources and need among religious institutes. California Louisiana Culver City Religious Sisters of Charity Lafayette Sisters of the Most Holy Sacrament Fremont Dominican Sisters of Mission San Jose New Orleans Brothers of the Sacred Heart Sisters of the Holy Family Maryland Los Angeles Immaculate Heart Community Baltimore School Sisters of Notre Dame Los Gatos Society of Jesus—USA West Province Massachusetts Menlo Park Corpus Christi Monastery Brighton Sisters of St. Joseph Orange Sisters of St. Joseph Marlborough Sisters of St. Chretienne San Francisco Sisters of the Presentation Sisters of St. Anne of the Blessed Virgin Mary Milton Holy Union Sisters Colorado Springfield Stigmatine Fathers and Brothers Colorado Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration Michigan Springs Adrian Adrian Dominican Sisters Denver Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity Allen Park Sisters of Mary Reparatrix Snowmass St. Benedict’s Monastery Detroit PIME Missionaries Connecticut Province of St. Joseph of the Capuchin Order Hartford Missionaries of Our Lady of La Salette Monroe Servants of Jesus Putnam Daughters of the Holy Spirit Saginaw Sisters of St. Clare Wilton Sisters of the Congregation de Notre Dame Minnesota District of Columbia Little Falls Franciscan Sisters Washington US Province of the Religious of Jesus and Mary St. Joseph Sisters of the Order of St. -

U.S. Catholic Sisters Urge Congress to Support Iran Nuclear Deal

U.S. Catholic Sisters Urge Congress to Support Iran Nuclear Deal Name Congregation City/State Lauren Hanley, CSJ Sisters of St Joseph Brentwood NY Seaford , NY Elsie Bernauer, OP Sisters of St. Dominic Caldwell, NJ Grace Aila, CSJ Sisters of St. Joseph NY, NY Sister Lisa Paffrath, CDP Sisters of Divine Providence Allison Park, PA Kathleen Duffy, SSJ Sisters of St. Joseph, Philadelphia Glenside, PA Joanne Wieland, CSJ Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet St. Paul, MN Sister Cathy Olds, OP Adrian Dominican Lake Oswego, OR Elizabeth Rutherford, osf Srs.of St. Francis of CO Springs Los Alamos, NM charlotte VanDyke, SP Sisters of Providence Seattle, WA Pamela White, SP Sisters of Providence Spokane, WA Patricia Hartman, CSJ Sisters of St. Joseph of Orange Orange, CA Donna L. Chappell, SP Sisters of Providence Seattle , WA Marie Vanston, IHM Srs. Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Scranton, PA Stephanie McReynolds, OSF Sisters of Saint Francis of Perpetual Adoration CO Springs, CO Joanne Roy, scim Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Saco, ME Lucille Dean, SP Sisters of Providence Great falls, MT Elizabeth Maschka, CSJ Congregation of St. Joseph Concordia, KS Karen Hawkins, SP Sisters of Providence Spokane, WA Sister Christine Stankiewicz, C.S.S.F. Felician Sisters Enfield, CT Mary Rogers, DC Daughters of Charity Waco, TX Carmela Trujillo, O.S.F. Sisters of Saint Francis of Perpetual Adoration CO Springs, CO Sister Colette M. Livingston, o.S.U. ursuline Sisters Cleveland, OH Sister Joan Quinn, IHM Sisters of IHM Scranton, PA PATRICIA ELEY, S.P. SISTERS OF PROVIDENCE SEATTLE, WA Madeline Swaboski, IHM Sisters of IHM Scranton, PA Celia Chappell, SP Sisters of Providence Spokane, WA Joan Marie Sullivan, SSJ Sisters of St. -

To Download the Congregations List

Prayers for Peace November 3, 2020 Election Day Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Carmelite Sisters Hamden, CT Reno, Nevada Benedictine Sisters Mother of God Monastery Claretian Missionary Sisters, Watertown, SD Miami, FL Benedictine Sisters Comboni Missionary Sisters of Baltimore Congregation de Notre Dame Benedictine Sisters in US of Brerne, Texas Congregation of Divine Providence Benedictine Sisters Congregation of Notre Dame of Cullman Alabama Blessed Sacrament Province Benedictine Sisters Congregation of Sisters of St Agnes of Elizabeth , NJ Congregation of St Joseph Benedictine Sisters Cleveland, OH of Erie, PA Benedictine Sisters Congregation of the Holy Cross of Newark, DE Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Family Benedictine Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, of Naareth Clyde, MO Congregation of the Humility of Mary Benedictine Sisters Davenport, Iowa of Pittsburgh Consolata Missionary Sisters Benedictine Sisters of St Paul's Monastery of Belmont, MI St Paul, MN Daughters of Charity Benedictine Sisters USA of Virginia Daughters of Mary and Joseph California Benedtictines at Benet Hill Monastery Daughters of the Charity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Bernadine Franciscan Sisters USA delegation Brigidine Sisters Daughters of the Heart of Mary San Antonio, TX US Province Carmelite Sisters of Charity Daughters of Wisdom Vedruna Dominican Sisters of Adrian, MI 1 Prayers for Peace November 3, 2020 Election Day Dominican Sisters Little Company of Mary Sisters of Caldwell, NJ USA Dominican Sisters of Mission Little Sisters of the -

The Cult of Saints in Religious Orders: the Example of the Congregation of the Felician Sisters

Vol. 13 FOLIA HISTORICA CRACOVIENSIA 2007 L ucyna R o tter THE CULT OF SAINTS IN RELIGIOUS ORDERS: THE EXAMPLE OF THE CONGREGATION OF THE FELICIAN SISTERS In every order or monastic congregation a group of ‘favourite’ saints can be selected. The reasons differ. Most often the foremost place goes to the congrega tion’s founder or founders. It should be emphasized that in a number of orders, monastic congregations, monasteries, or abbeys the cult is given to benefactors and founders not formally canonized by the Church - for example in the abbeys of the Benedictine Sisters in Staniatki-Klemens, Reclawa and Wizenna1. The other reason for the particular veneration of a saint was the fact of his composing a rule a given congregation followed. Often founder and ‘rule provider’ are one and the same person, but there are also cases when the founder of the order or congregation uses a rule composed by someone else and which is widely known. For example: Saint Norbert von Genepp introduced the Rule of Saint Augustine to the nuns of the Norbertine Order that he founded2. The other group of saints venerated with a particular cult in congregations are those recognised as patrons or protectors of their congregations and saints and be atified coming from the ranks of their order. Deliberately, I avoid saints whose cult developed in a specific monastic church because of the location of a celebrated fig ure, picture, or relic not connected in any other way with the congregation. For such a cult does not always cover the whole monastic order but is characteristic only for a specific monastery or a province at the most. -

Stop Trafficking! Awarenessadvocacyaction

Stop Trafficking! AwarenessAdvocacyAction Anti-Human Trafficking Newsletter January 2020 Vol. 18 No. 1 FocusJean Schafer, SDS Founder and Publisher of Stop Trafficking Newsletter Retires Jean Schafer, SDS, founder of the Stop Trafficking Newsletter, has retired from the newsletter she has published for the past 17 years. Jean is a member of the Sisters of the Divine Savior (SDS Salvatorian Sisters) and currently resides in California. In 1989 she was elected Superior General of the Congregation’s 1200 members serving in 27 countries. She served in that capacity for 12 years. As a member of the Rome-based International Union of Superiors General (UISG) Jean became aware of the global scourge of human trafficking. Her Order, along with many other women’s religious orders, undertook a ministry of educating "As I reflect back over the people about human trafficking and working as advocates for its victims. years of this ministry of Returning from the central Mother House in Rome in 2002, Jean took sabbatical preparing issues of 'Stop time and then relocated to California to begin anti human trafficking efforts. Trafficking' it reminds me of She started the ‘Stop Trafficking’ e-newsletter, now in its 17th year, and co-directed the parable of the mustard SDS Hope House, a home for women coming out of situations of enslavement. seed — a small first step In 2016 management of the home was transferred to another faith-based group. that grew and grew into a Jean then took up ministry to refugees, tutoring English-as-a-Second Language (ESL) to women in their homes. -

© 2013 Shannen Dee Williams ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2013 Shannen Dee Williams ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BLACK NUNS AND THE STRUGGLE TO DESEGREGATE CATHOLIC AMERICA AFTER WORLD WAR I By SHANNEN DEE WILLIAMS A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Deborah Gray White and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Nuns and the Struggle to Desegregate Catholic America after World War I by SHANNEN DEE WILLIAMS Dissertation Director: Deborah Gray White Since 1824, hundreds of black women and girls have embraced the religious state in the U.S. Catholic Church. By consecrating their lives to God in a society that deemed all black people immoral, black Catholic sisters provided a powerful refutation to the racist stereotypes used by white supremacists and paternalists to exclude African Americans from the ranks of religious life and full citizenship rights. By dedicating their labors to the educational and social uplift of the largely neglected black community, black sisters challenged the Church and the nation to live up to the full promises of democracy and Catholicism. Yet, their lives and labors remain largely invisible in the annals of American and religious history. This is especially true of their efforts in the twentieth century, when black sisters pried opened the doors of Catholic higher education, desegregated several historically white congregations, and helped to launch the greatest black Catholic revolt in American history. This dissertation unearths the hidden history of black Catholic sisters in the fight for racial and educational justice in the twentieth century. -

Poor Health, Early Learning Affect Sophia

VOL. 18 NO. 1 2019 Poor Health, Early Learning Affect Sophia By +Sister Mary Felicita Zdrojewski, CSSF Sophia Camille, the daughter of Josephine and Joseph Truszkowski, was born on May 16, 1825, in Kalisz, Poland. Premature, she was baptized immediately. Eight months later, on January 11, 1826, in the collegiate church of St. Joseph, the sacrament of Baptism was conferred with full ritual by the Reverend Melchior Kierzkiewicz. Frances Langowska and Martin Ciechanowski were Sophia’s godparents. Surrounded with love and the best of care, Sophia’s health improved. She grew strong, inquisitive and eager to learn. She reigned as the sole darling of the household. As the years went on, she shared this love with her younger brothers and sisters: Valerie, Walter, Joseph, Louise, Bruno and Hedwig. Sophia was unselfish and sensitive. Her heart responded to suffering and poverty. Enterprising and entertaining, she knew how to obtain coins from relatives and friends to give to the poor. Although she was generous, Sophia was not free from childish tantrums and fits of stubbornness. At times the favored child was distressed to tears if met with conflict or opposition. Although Josephine Truszkowska was vigilant over her children’s behavior, many of Sophia’s displays were overlooked since the doctors had cautioned against placing undue pressures on the child. The young Anastasia Kotowicz, daughter of Frances and Valentine Langowski, was only eleven years older than Sophia when she began tutoring the eldest Truszkowski child. Educated by the Ursuline Nuns in Wroclaw, she was versed in languages and had the experience of extensive travel outside of Poland. -

The Franciscan Way of Sozology

Felician Franciscan Sisters Congregational Central Office for Winter 2011: Vol. 4, No. 7 Justice&Peace The Franciscan Way of Sozology In the last century, a rapid growth in technology and industry took place, causing a serious breach in the ecological balance throughout the world. Its negative effects are manifested in human life as well as in the entire created world. Due to the huge range of issues to be dealt with, different institutions and organizations on both regional and international levels have addressed this problem. This issue has also been addressed by research and public opinion poll centers around the world. The combined efforts of ecologists, geologists, geographers and representatives in the fields of science, technology, economics and humanities gave birth to an interdisciplinary branch of science known as sozology, sometimes considered as a part of applied ecology. It is defined as the study of the effects and consequences of the changes in the environment caused by the socio- The following are a few statements in which ecology is economic activities of humankind and of the successful unduly mixed up with religion: prevention and reduction of the negative consequences. Traces of ecological thinking can be found not only in 66 Thomas Berry from Fordham University in the United all past epochs and cultures, but even in the present States claims that humankind’s responsibility for the where its influence can be seen in almost every field ecology “is the highest priority on both religious and of human activity. Its extraordinary popularity and huge spiritual levels.”1 range of influence inclines one to believe that ecology responds to the deepest human needs, including the 66 The Global Forum held in Moscow in 1990, which search for the truth about the world and humankind’s brought together delegates from 83 countries, urged place in it. -

Convents in Kraków in the 20 Th Century

PRACe GeoGRAFICzne, zeszyt 137 Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ Kraków 2014, 159 – 173 doi : 10.4467/20833113PG.14.014.2159 Convents in KraKów in the 20 th Century Justyna Liro Abstract : Religious orders are clearly noticeable in the geographic space of major cities in Poland. The purpose of the paper is to analyse the location factors for religious orders in Kraków, including the location of the most important houses and their related activity in the city. Religious orders have been present in Kraków since its beginnings. The paper covers convents run by the Roman Catholic Church within the borders of Kraków. The paper is focused on the 20th century when a considerable increase of the number of religious orders and general spatial development of the city was observed. The data for this paper was obtained from church and secular sources, as well as land surveys. In addition, changes in the spatial distribution of religious orders and monastic houses operating in Kraków in the 20th century as well as modifications in their functions were analysed. The largest concentration of monastic houses is Kraków’s historic core. The actual distribution of convents is a result of centuries- old traditions and depends on numerous factors such as the capital city function of Kraków in effect until the end of the 16th century and the rank of religious administration ( bishopric ). A further increase in the number of monastic houses was also due to the spatial growth of the city and the general development of monastic life. Religious orders were characterised by various endogenous and exogenous functions.