The Beginnings of the Episcopal Church in Connecticut M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

Testing the Elite: Yale College in the Revolutionary Era, 1740-1815

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Theses and Dissertations 2021 TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815 David Andrew Wilock Saint John's University, Jamaica New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations Recommended Citation Wilock, David Andrew, "TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 255. https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations/255 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by St. John's Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of St. John's Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY to the faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY of ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES at ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY New York by David A. Wilock Date Submitted ____________ Date Approved________ ____________ ________________ David Wilock Timothy Milford, Ph.D. © Copyright by David A. Wilock 2021 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 David A. Wilock It is the goal of this dissertation to investigate the institution of Yale College and those who called it home during the Revolutionary Period in America. In so doing, it is hoped that this study will inform a much larger debate about the very nature of the American Revolution itself. The role of various rectors and presidents will be considered, as well as those who worked for the institution and those who studied there. -

An Histokical Study of the Powers and Duties of the Peesidency in Yale College

1897.] The Prendency at Tale College. 27 AN HISTOKICAL STUDY OF THE POWERS AND DUTIES OF THE PEESIDENCY IN YALE COLLEGE. BY FRANKLIN B. DEXTER. Mr OBJECT in the present paper is to offer a Ijrief histori- cal vieAV of the development of the powers and functions of the presidential office in Yale College, and I desire at the outset to emphasize the statement that I limit myself strictl}' to the domain of historical fact, with no l)earing on current controA'ersies or on theoretical conditions. The corporate existence of the institution now known as Yale University dates from the month of October, 1701, when "A Collegiate School" Avas chartered b}^ the General Assembly of Connecticut. This action was in response to a petition then received, emanating primarily frojn certain Congregational pastors of the Colon}', who had been in frequent consnltation and had b\' a more or less formal act of giving books already taken the precaution to constitute themselves founders of the embiyo institution. Under this Act of Incorporation or Charter, seA'en of the ten Trustees named met a month later, determined on a location for tlie enterprise (at Sa3'brook), and among otlier necessary steps invited one of the eldest of their numl)er, the Reverend Abraham Pierson, a Harvard graduate, " under the title and cliaracter of Kector," to take the care of instrncting and ordering the Collegiate School. The title of "Collegiate School" was avowedly adopted from policy, as less pretentious than that to Avhich the usage at Harvard for sixty years had accustomed them, and tliere- 28 American Antiquarian Society. -

Alexander Hamilton and the Development of American Law

Alexander Hamilton and the Development of American Law Katherine Elizabeth Brown Amherst, New York Master of Arts in American History, University of Virginia, 2012 Master of Arts in American History, University at Buffalo, 2010 Bachelor of Science in Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, 2004 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia May, 2015 This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of Matthew and Theresa Mytnik, my Rana and Boppa. i ABSTRACT ―Alexander Hamilton and the Development of American Law,‖ is the first comprehensive, scholarly analysis of Alexander Hamilton‘s influence on American jurisprudence, and it provides a new approach to our understanding of the growth of federal judicial and executive power in the new republic. By exploring Hamilton's policy objectives through the lens of the law, my dissertation argues that Hamilton should be understood and evaluated as a foundational lawmaker in the early republic. He used his preferred legal toolbox, the corpus of the English common law, to make lasting legal arguments about the nature of judicial and executive power in republican governments, the boundaries of national versus state power, and the durability of individual rights. Not only did Hamilton combine American and inherited English principles to accomplish and legitimate his statecraft, but, in doing so, Hamilton had a profound influence on the substance of American law, -

February/March 2008 Leaflet at Harvard Volume LXXVI, No

Christ Church Cambridge The Episcopal Church in Harvard Square. Zero Garden Street Cambridge, MA 02138-3631 phone (617) 876-0200 fax (617) 876-0201 www.cccambridge.org Staff The Rev. Joseph O. Robinson Rector The Rev. Jeffrey W. Mello Assistant Rector The Rev. Karen B. Montagno Associate Priest Stuart Forster Director of Music & Organist Elisabeth (Buffy) Gray Sabbatical Music Director Tanya Cosway Interim Parish Administrator Dona O’Donnell Financial Administrator Jerry Kucera, Hernan Moya, Ron Wilburn, Sextons The Rev. Benjamin King Episcopal Chaplain February/March 2008 Leaflet at Harvard Volume LXXVI, No. 2 Officers & Vestry A different look for the Leaflet… Karen Mathiasen Senior Warden Sally Kelly Junior Warden Lent through Easter is the busiest time of the year for church offices, especially this year Mark MacMillan Treasurer with changes in staff, construction in the office, and work to upgrade many of our Tanya Cosway Asst. Treasurer communications. Recognizing how important communication is at this time of year, your Jude Harmon Clerk Interim Parish Administrator begs your indulgence as we simplify our format for the next Amey Callahan few editions of the Leaflet. You’ll still find out what’s happening at CCC and how you Timothy Cutler can be involved, including education and mission activities, events inside and outside the Timothy Groves parish, and the Holy Week schedule. You can read about recent events and messages Peggy Johnson from the Rector and the Wardens. The Liturgical Rota for March will be mailed out Samantha Morrison Nancy Sinsabaugh under separate cover. Wendy Squires Mimi Truslow Normally we would begin with a message from the Rector. -

Itbe £Aet Haven Citisen "East Haven's

"East Haven't "East Haven's Own Own Newspaper" ITbe £aet Haven Citisen Newspaper" VOL. I., No. 17 EAST HAVEN, CONN., FRIDAY, JUNE 18, 1937 PRICE 5 CENTS Stone Church Local Post Passes Baptises 13 PROMINENT IN FIRST GRADUATION OF E.H.H.S. Inspection Service Last Sunday Children's Day was The National Headquarters of the held at the morning service of the American Legion has originated an Old Stone Church. Thirteen chil inspection service to check the ac dren were baptized by Dr. Edwin tivities of all posts and ascertain D. Harvey, interim pastor of tlie whether or not they are on their church, with the aid of Mr. E. A. toes. This inspection is divided in Cooper, senior deacon. to five main groups as follows:— The children baptised were as fol Post Organization, 10 items; Mem lows: Paula Gale Andrews, daugh bership, 5 items; Americanism, 3 ter of Mr." and Mrs. Paul A'ndrews; iteriis; Community Service, 12 Jerry Gordon and Joyce Irma Olson, items; and Miscellaneous, 9 items. ton Johnson, and Henry John In all there are 61 questions which Martin Olson; Robert Christopher must be answered and all these rep Wood, son of Mr. and Mrs. Cyril resent individual moves and activ Wood; Carol Wilson and Audrey ities for the benefit of the Post and Jane Redtield, daughters of Mr. and the town at large. Mrs. Leslie Redfield; Clifford Fred The Harry Bartlett Post, No. 89, erick, Marilyn Lois and Norma American Legion, of East Haven, Miller De Wolf, son and daughters of Mr. and Mrs. -

A Yale Book of Numbers, 1976 – 2000

A Yale Book of Numbers, 1976 – 2000 Update of George Pierson’s original book A Yale Book of Numbers, Historical Statistics of the College and University 1701 – 1976 Prepared by Beverly Waters Office of Institutional Research For the Tercentennial’s Yale Reference Series August, 2001 Table of Contents A Yale Book of Numbers - 1976-2000 Update Section A: Student Enrollments/Degrees Conferred -- Total University 1. Student Enrollment, 1976-1999 2. (figure) Student Enrollment, 1875-1999 3. (figure) Student Enrollment (Headcounts), Fall 1999 4. Student Enrollments in the Ivy League and MIT, 1986-1999 5. Degrees Conferred, 1977-1999 6. Honorary Degree Honorands, 1977-2000 7. Number of Women Enrolled, University-Wide, 1871-1999 8. (figure) Number of Women Enrolled University-Wide, 1871-1999 9. Milestones in the Education of Women at Yale 10. Minority and International Student Enrollment by School, 1984-1999 Section B: International Students at Yale University 1. International Students by Country and World Region of Citizenship, Fall 1999 2. (figure) International Graduate and Professional Students and Yale College Students by World Region, Fall 1999 3. (figure) International Student Enrollment, 1899-1999 4. (figure) International Students by Yale School, Fall 1999 5. International Student Enrollment, 1987-1999 6. Admissions Statistics for International Students, 1981-1999 Section C: Students Residing in Yale University Housing 1. Number of Students in University Housing, 1982-1999 2. Yale College Students Housed in Undergraduate Dormitories, 1950-1999 3. (figure) Percentage of Yale College Students Housed in the Residential Colleges, 1950-1999 Section D: Yale Undergraduate Admissions and Information on Yale College Freshmen 1. -

1789 Journal of Convention

Journal of a Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the States of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and South Carolina 1789 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL OF A. OF THB PROTESTA:N.T EPISCOPAL CHURCH, IN THE STATES OF NEW YORK, MARYLAND, NEW JERSEY, VIRGINIA, PENNSYLVANIA, AND DELAWARE, I SOUTH CAROLINA: HELD IN CHRIST CHURCH, IN THE CITY OF PHILIlDELPBI.IJ, FROM July 28th to August 8th, 178~o LIST OF THE MEMBER5 OF THE CONVENTION. THE Right Rev. William White, D. D. Bishop of the Pro testant Episcopal Church in the State of Pennsylvania, and Pre sident of the Convention. From the State ofNew TorR. The Rev. Abraham Beach, D. D. The Rev. Benjamin Moore, D. D. lIT. Moses Rogers. -

Jarvis Family;

THE JARVIS FAMILY; THE DESCENDANTS OF THE FIRST SETTLEHS OF THE NA)rE I~ MASSACHUSETTS AXJ) LOXG IS~ASD, THOSt: \YHO HAVE MOUE llt:ct;.,.,.LY ,s!,.'TT!,Ell IX 0THt:R l'AKTS ut· TIIJ;: UNITED HTATE.,; AXI) BKITl:,<H .'l.llt:RICA. C''OLLJ!:CTt:D AND COXJ"IU:O nY GEORGE A ..JAR\.IS, w Nr,:n· Yo1:K; GEORGE .MlJRRA y JARYIS, OP OTTAWA, CAXAllA; WILLIAM JARVIS WETl[OHJ,;, ot· NEw YoRK: .ALli'RED fL\HDlNG, o, Biwc.Krsx, N. Y. IIAHTFOHD: Pm:ss OP TuF: c .. ~.:. LOCKWOOI) ,I; Bi:AlNAltll COMPANY. } Si !I. PREF.A.CE. ,\ HUl'T fin, yeal'l' have now cbpsed i-iuce we, first couceive,l the project of tmdng the gcm•alogy of tlw Jarvi,- Family in this country. Lc•tten; were written tn prominent men of the name in different parts of tht· l;nited State:< and British America, from many of whom favorable rcsponi:cs wen• r<ie<•iv, .. l. Severa! in Canada, Nova S<·otia, aml );',,w Bnmswick were highly intere:;ted, ofTning their valunhlc coll,•ction,-. to :Lid tht• entl'rprisc. Many, al"o, in the United· States were cqunl·ly intl're:,;tcd. nml oJicn.-<l their eull,-ction:,; an,i any aid within their powt•r. The addres..-<es of ,Iiffercnt members of famili,.,. were sought out and solicited, u.nd hundreds of letter.; written for :my records, ,:kl'tehcs, steel and lithograph engravings, or any items of history c~mnccted with the n:mw, worthy of being transmitted to posterity. :Many responded promptly; some, by indifference, delayed the work; while others ncgll'Ctcd lLltogcthl'r to notice our applications. -

Freedom of the Press: Croswell's Case

Fordham Law Review Volume 33 Issue 3 Article 3 1965 Freedom of the Press: Croswell's Case Morris D. Forkosch Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Morris D. Forkosch, Freedom of the Press: Croswell's Case, 33 Fordham L. Rev. 415 (1965). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol33/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Freedom of the Press: Croswell's Case Cover Page Footnote The instant study was initiated by Professor Vincent C. Hopkins, S.J., of the Department of History, Fordham University, during 1963. In the spring of 1964 be died, leaving an incomplete draft; completion necessitated research, correction, and re-writing almost entirely, to the point where it became an entirly new paper, and the manuscript was ready for printing when the first olumev of Professor Goebel's, The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton (1964), appeared. At pages 775-SO6 Goebel gives the background of the Croswell case and, because of many details and references there appearing, the present article has been slimmed down considerably. However, the point of view adopted by Goebel is to give the background so that Hamilton's participation and argument can be understood. The purpose of the present article is to disclose the place occupied by this case (and its participants) in the stream of American libertarian principles, and ezpzdally those legal concepts which prevented freedom of the press from becoming an everyday actuality until the legislatures changed the common law. -

Open Dissertation Final.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts “BREAKING OVER THE BOUNDARIES OF THE PARTY:” THE ROLE OF PARTY NEWSPAPERS IN DEMOCRATIC FACTIONALISM IN THE ANTEBELLUM NORTH, 1845-1852 A Dissertation in History by Matthew Isham © 2010 Matthew Isham Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Matthew Isham was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark E. Neely, Jr. McCabe-Greer Professor in the American Civil War Era Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Anthony E. Kaye Associate Professor of History Matthew Restall Edwin Earle Sparks Professor of Colonial Latin American History, Anthropology and Women‟s Studies J. Ford Risley Associate Professor of Communications Carol Reardon Director of Graduate Studies George Winfree Professor of American History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT In the first half of the nineteenth century partisan newspapers performed a crucial function in the creation and maintenance of the Democratic Party. Partisan newspapers sprang up rapidly throughout the country in large cities and small towns, coastal ports and western settlements. For many of their readers, these newspapers embodied the party itself. The papers introduced readers to the leaders of their parties, disseminated party principles and creeds, and informed them of the seemingly nefarious machinations of their foes in other parties. They provided a common set of political ideals and a common political language that linked like- minded residents of distant communities, otherwise unknown to each other, in a cohesive organization. In the North, the focus of this dissertation, these newspapers interpreted regional economic development and local political issues within the context of their partisan ideals, providing guidance to readers as they confronted the parochial issues of their community. -

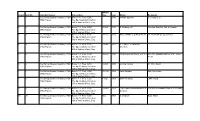

Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Month/ Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 the Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- 1796) Papers

Month/ Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 1740 William Spencer S. Seabury, Sr. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 2 2 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Oct 1753 S. Seabury, Sr. Thomas Sherlock, Bp. of London 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 3 3 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 24-Dec 1755 Moses Mathers & Noah Wells Dr. Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 4 4 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Jan 1757 S. Clowes, Jr. and Wm. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Sherlock Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 5 5 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 28-Feb 1757 Philip Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) Rev. Mr. Obadiah Mather & Mr. Noah 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Wells Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 6 6 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 30-Oct 1760 Archbp. Secker Dr. Wm. Smith 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 7 7 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 16-Feb 1762 Jane Durham Mrs. Ann Hicks 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 8 8 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 4-Sep 1763 Sam'l Seabury John Troup 1796) Papers The Bp.