Greater Munich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction

INTRODUCTION IN THE LECTURE ROOMS that lined the narrow, crowded streets of the "Latin quarter" of Paris, there evolved during the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries an approach to learning that would dominate the intellectual world of northern Eu rope for the next three hundred years. This new method of thought, known to historians as scholasticism, held out the intoxicating possibility that, through reason and the powerful tool of Aristotelian logic, men could resolve the seeming con tradictions between faith and reason, Christian truth and Greek science, and attain insights into the nature of the world, of man, and of God. In these same years, as the teaching masters of Paris gained a corporate identity as the University ofParis, they formally adopted this new intellectual program as the basis oflearning and instruction. Subsequently, these Parisian methods became the model for dozens of universities founded in England, Spain, the Low Countries, and the Holy Roman Empire. As a result, scholasticism-with its veneration of Aristotle, cultivation oflogic, and enthusiasm for disputation and debate-became synonymous with northern European academic life for the remainder of the medieval era. Some two hundred years after the emergence of scholas ticism, another intellectual movement, known as Renaissance humanism, began to evolve in the rich and populous cities of northern Italy. Unlike the scholastics, the disciples of this new cultural movement had scant interest in Aristotelian thought, theological speculation, and sophisticated logical concepts. Spurred by a new appreciation of the classics, these Italian thinkers-in particular Petrarch (1304-1374)-warmed to the ix Introduction - Ciceronian ideal of the studia humanitatis, an approach to learn ing that stressed literary and moral rather than philosophical training. -

A Study of the Greater Bay Area and the Tokyo Metropolitan Area in Internationalising Higher Education

A Study of the Greater Bay Area and the Tokyo Metropolitan Area in Internationalising Higher Education YIM Long Ho, Doctor of Policy Studies, Lingnan University Introduction With a vision to compete with the San Francisco Bay Area, the New York Metropolitan Area, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Area (also known as the Greater Tokyo Area), China is determined to develop the Greater Bay Area that includes 9 mainland cities and 2 Special Administration Regions. The Tokyo Metropolitan Area consists of Tokyo and 3 prefectures: Saitama, Chiba, and Kanagawa. According to the OECD, the Tokyo Metropolitan Area accounts for 74% of Japan’s GDP. From 2000 to 2014, Tokyo alone has generated 37% of Japan’s GDP (OECD, 2018). Tokyo has also become the world’s largest metropolitan economy in 2017 (Florida, 2017). While the knowledge-based economy has been the backbone of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area, where speed, connectivity, innovation, knowledge and information have determined its success, the overconcentration of industries in Tokyo and its relatively less international higher education system also demand attention (Otsuki, Kobayashi , & Komatsu, 2020). Despite there has been a prolonged development in internationalising the Japanese higher education, such as the ‘Global 30’ initiative, and the Figure 1. Tokyo and the Tokyo Metropolitan Area. establishment of overseas higher education Source: “Response to urban challenges by global cities within institutions, the lack of “internationalisation” can be developmental states: The case of Tokyo and Seoul” by Khan, S., seen in the socio-economic context of Japan Khan, M., & An, S. K., 2019, p. 376. (Mizuno, 2020). Figure 2. The Greater Bay Area. -

Bavaria: Statistics 2020

Bavaria: Statistics 2020 www.statistik.bayern.de Publication service The avarian State Office for Statistics issues more than 400 publications annually. The current list of publications is available on the Internet as a file but can also be provided free of charge in printed form. Free of charge Publication service is the download of most publications, All publications are available e. g. statistical reports (PDF or Excel format). on the Internet at www.statistik.bayern.de/produkte Subject to charge are all print versions (also of statistical reports), data carriers and selected files (e. g. of directories, of contributions, of the yearbook). Explanation of symbols Rounding 0 less than half of 1 in the last digit occupied, In general totals have been rounded and therefore but more than zero may not sum. As a result minor deviations from the – no figures or magnitude ero reported totals may occur when individual figures are / no data because the numerical value is not added up. When totals are shown as a percentage, sufficiently reliable the sum of the individual figures may not be 100 due to rounding. In general the sum of percentages is not · numerical value unknown or not to be disclosed made to be 100 . ... data will be available later x cell blocked for logical reasons Abbreviations ( ) limited informational value because the numerical value is of limited statistical reliability € euro p provisional numerical value EU European Union r corrected numerical value ALC association of local councils s estimated numerical value ha hectare (10,000 m2) D average hl hectolitres (100 litres) ‡ corresponds to mill. -

München to Rosenheim

MÜNCHEN TO ROSENHEIM © Copyright Dovetail Games Ltd, all rights reserved Release Version 1.0 Train Simulator – München to Rosenheim CONTENTS CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 2 1 ROUTE INFORMATION ................................................................................................... 3 1.1 History .................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 The Route ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Focus Time Period ................................................................................................................ 4 1.4 Rolling Stock ........................................................................................................................ 4 2 GETTING STARTED ........................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Recommended Minimum Hardware Specification .................................................................... 5 3 THE DB BR423 ................................................................................................................ 6 3.1 Cab Controls ......................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Keyboard Guide ................................................................................................................... -

Here Is the Title the Subtitle to Content

Briefing: Bavaria & Munich’s Economic and Cultural Assets Denver Leadership Exchange, October 2017 Page Introduction to Bavaria A short film https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-rckHpEUnKg Page Quick Facts Munich vs. Denver Population Population ▪ City of Munich: 1.5 mn ▪ City of Denver: 700,000 ▪ Metro Munich: 2.9 mn ▪ Metro Denver: 2.8 mn Important Industries Important Industries ▪ Automotive/Mobility ▪ Aerospace/Aviation ▪ Construction/Engineering ▪ Health/MedTech/Pharma ▪ Creative Industries ▪ Energy/Cleantech Median Income: € 47,868 Median Income: $60,260 Favorite Sports Team: Favorite Sports Team: Favorite Drink: Favorite Drink: Page Bavaria & Munich your ideal location for growth in EMEA Key Success Factor #1: Strong economy in the heart of the EU Key Success Factor #2: Powerful and diverse company landscape Key Success Factor #3: Europe’s leading innovation hub Key Success Factor #4: Supportive government and politics Key Success Factor #5: High quality of living Page #1 Strong economy in the heart of Europe Bavaria at a glance Hamburg Berlin Hanover Düsseldorf Erfurt Dresden Frankfurt 27,200 sqm € 568 bn Germany‘s largest Federal State Nuremberg GDP (2016) / #7 in EU 12.8 mn Stuttgart 14.7% Munich inhabitants (16% of Germany) growth (2010 to 2016) 3.5% € 183 bn unemployment (2016) export volume (2016) Page #1 Strong economy in the heart of Europe In the center of Europe Helsinki Well connected to 500 mn Oslo Stockholm customers within the EU Riga Dublin Kiev London Warsaw Brussels Paris Munich Budapest 1h Zurich Vienna Bucharest 2h -

Cheer Divisions Special Divisions

Version: 08.11.2017 German All Level Championship 2017 - South-East List of Participants # Team Club City Country Cheer Divisions Peewee Cheer Level 1 1 CCL FRANTIC Cheerleader Club Leipzig e.V. Leipzig GER 2 NBC Little Galaxy TSV Obernsees v 1909 e.V. Mistelgau GER 3 Fierce Athletics Sparkle TV 1873 Würzburg e.V. Würzburg GER 4 Loopy Arrows ARROWS Pirna e.V. Pirna GER 5 Rosenheim Cheer Athletics Minis MTV Rosenheim 1885 e.V. Rosenheim GER 6 Shorty Angels Great Gera Skates e.V. Gera GER 7 FA Fireflies TSV Haar e.V. Haar GER 8 Teufelinos CVV Cheermania e.V. Auerbach GER Peewee Cheer Level 2 1 CCL FERAL Cheerleader Club Leipzig e.V. Leipzig GER 2 Minimaniacs Riesaer Cheerleader Verein Riesa GER 3 Little Arrows ARROWS Pirna e.V. Pirna GER 4 Yuanjia School Cheerleading Sunshine China Cheerleading Association Nanjing CHN Junior Allgirl Cheer Level 2 1 Glamorous - Sparkle TSG Salach e.V. Salach GER 2 Rosenheim Cheer Athletics Teens MTV Rosenheim 1885 e.V. Rosenheim GER 3 United Juniors 1. FC Bayreuth Bayreuth GER Junior Allgirl Cheer Level 3 1 CCL FIERY Cheerleader Club Leipzig e.V. Leipzig GER 2 Fierce Athletics Rise TV 1873 Würzburg e.V. Würzburg GER 3 EMC - Rising Stars SpVgg 1904 Erlangen e.V. Erlangen GER 4 Rising Arrows ARROWS Pirna e.V. Pirna GER 5 Little Angels Great Gera Skates e.V. Gera GER 6 Black Maniacs CVV Cheermania e.V. Auerbach GER 7 FA Wildfire TSV Haar e.V. Haar GER 8 Little Bears 1. Cheerleaderverein Bamberg Lucky Bears 2002 e. -

3.1•The Randstad: the Creation of a Metropolitan Economy Pietertordoir

A. The Economic, Infrastructural and Environmental Dilemmas of Spatial Development 3.1•The Randstad: The Creation of a Metropolitan Economy PieterTordoir Introduction In this chapter, I will discuss the future scenarios for the spatial and economic devel- opment of the Randstad (the highly urbanized western part of the Netherlands). Dur- ing the past 50 years, this region of six million inhabitants, four major urban centers and 20 medium-sized cities within an area the size of the Ile de France evolved into an increasingly undifferentiated patchwork of daily urban systems, structured by the sprawl of business and new towns along highway axes. There is increasing pressure from high economic and population growth and congestion, particularly in the northern wing of the Randstad, which includes the two overlapping commuter fields of Amsterdam and Utrecht. Because of land scarcity and a rising awareness of environ- mental issues, the Dutch planning tradition of low-density urban development has be- come increasingly irrelevant. The new challenge is for sustainable urban development, where the accommoda- tion of at least a million new inhabitants and jobs in the next 25 years must be com- bined with higher land-use intensities, a significant modal shift to public transporta- tion, and a substantial increase in the quality and diversity of the natural environment and the quality of life in the region.1 Some of these goals may be reached simultane- ously by concentrating development in high-density nodes that provide a critical mass for improved mass transit systems, rendering an alternative for car-dependent com- muters. Furthermore, a gradual integration of the various daily urban systems may benefit the quality and diversity of economic, social, natural, and cultural local envi- ronments within the polynuclear urban field. -

Wachstumsstandort Ingolstadt Bevölkerungsentwicklung 1990 Bis 2007

Wachstumsstandort Ingolstadt 140.000 135.000 130.000 125.000 Bevölkerungsentwicklung 1990 bis 2007 120 000 .000 115.000 110 000 .000 105.000 100.000 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 Würzburg 1999 Regensburg 2000 2001 Ingolstadt 2002 2003 Fürth 2004 2005 2006 Erlangen 2007 Bevölkerungsstruktur 2 Deutsche Ausländer Eingebürgerte 13% 4% Deutsche Deutsche ohne Spätaussiedler Migrations- 16% hintergrund 67% 3 145.000 140.000 135.000 (11. koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung der statistischen Landesämter) 130.000 koordinierte Bevölkerungsprognose 2006 bis 2025 125.000 120.000 Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung 115.000 110.000 105.000 100 000 .000 der 2006 statistischen 2007 2008 Landesämter) 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Regensburg 2016 Würzburg 2017 Ingolstadt 2018 2019 2020 Fürth 2021 2022 2023 2024 Erlangen 2025 Altersstruktur 4 Prognose des Einwohnerzuwachses in % 2006-2025 (11. koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung der statistischen Landesämter) Ingolstadt Oberbayern Regensburg München Fürth Augsburg Nürnberg Bayern Erlangen Würzburg 0 %1 %2 %3 %4 %5 %6 %7 %8 % 5 40.000 2006 35.000 2010 30.000 2015 2020 25.000 2025 20.000 15.000 10. 000 5.000 0 0-18 Jahre 19-39 Jahre 40-59 Jahre 60-74 Jahre ab 75 Jahre 6 Bruttoinlandsprodukt 1996-2006 9.000.000 Regensburg 8.000.000 Ingolstadt 7.000.000 ro uu 6.000.000 Würzburg 1 000. E Erlangen 5.000.000 Fürth 4.000.000 3.000.000 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 7 Prozentuale Steigerung des Bruttoinlandprodukts 1996-2006 Ingolstadt Regensburg Würzburg Erlangen Fürth München Nürnberg Augsburg Bayern Oberbayern 0 % 10 % 20 % 30 % 40 % 50 % 60 % 70 % 80 % 90 % 1008 % Bruttowertschöpfung Produzierendes Gewerbe 1996-2006 5. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of December, 2009 Club Fam

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of December, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 111BS 21847 AUGSBURG 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21848 AUGSBURG RAETIA 0 0 1 49 50 District 111BS 21849 BAD REICHENHALL 0 0 2 25 27 District 111BS 21850 BAD TOELZ 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21851 BAD WORISHOFEN MINDELHEIM 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21852 PRIEN AM CHIEMSEE 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21853 FREISING 0 0 0 48 48 District 111BS 21854 FRIEDRICHSHAFEN 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21855 FUESSEN ALLGAEU 0 0 1 33 34 District 111BS 21856 GARMISCH PARTENKIRCHEN 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21857 MUENCHEN GRUENWALD 0 0 1 43 44 District 111BS 21858 INGOLSTADT 0 0 0 62 62 District 111BS 21859 MUENCHEN ISARTAL 0 0 1 27 28 District 111BS 21860 KAUFBEUREN 0 0 0 33 33 District 111BS 21861 KEMPTEN ALLGAEU 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21862 LANDSBERG AM LECH 0 0 1 36 37 District 111BS 21863 LINDAU 0 0 2 33 35 District 111BS 21864 MEMMINGEN 0 0 0 57 57 District 111BS 21865 MITTELSCHWABEN 0 0 0 42 42 District 111BS 21866 MITTENWALD 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21867 MUENCHEN 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21868 MUENCHEN ARABELLAPARK 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21869 MUENCHEN-ALT-SCHWABING 0 0 0 34 34 District 111BS 21870 MUENCHEN BAVARIA 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21871 MUENCHEN SOLLN 0 0 0 29 29 District 111BS 21872 MUENCHEN NYMPHENBURG 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21873 MUENCHEN RESIDENZ 0 0 0 22 22 District 111BS 21874 MUENCHEN WUERMTAL 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21875 -

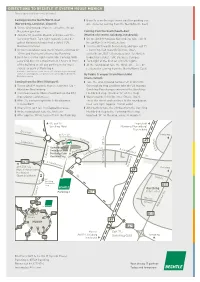

DIRECTIONS to BECHTLE IT SYSTEM HOUSE MUNICH Please Observe All Low-Emission Zones!

DIRECTIONS TO BECHTLE IT SYSTEM HOUSE MUNICH Please observe all low-emission zones! Coming from the North/North-East Bechtle is on the right-hand side (for parking see (Nuremberg, Landshut, airport): directions for coming from the North/North-East) On the A92 towards Munich, exit at the Kreuz Neufahrn junction Coming from the South/South-East Join the A9 towards Munich and take exit 70 – (Munich city centre, Salzburg, Innsbruck): Garching-Nord. Turn right towards Gewerbe- On the A8/A99 towards Nuremberg, take exit 13 – gebiet Hochbrück (industrial estate), TÜV, Kreuz München-Nord junction Business Campus Join the A9 towards Nuremberg and take exit 71 At the roundabout take the third exit, continue for – Garching-Süd towards Dachau, Ober- 100 m and then turn left onto the Parkring schleißheim, B471, Gewerbegebiet Hochbrück Bechtle is on the right-hand side. Parking: With (industrial estate), TÜV, Business Campus a parking disc for a maximum of 2 hours in front Turn right at the first set of traffic lights of the building or all-day parking in the multi- At the roundabout take the third exit ... (see di- storey car park at Parkring 4. rections for coming from the North/North-East) Parking is available at a reduced fee of € 4.50 per day for training/ conference participants. Car park tickets can be obtained from the By Public Transport from Munich Hbf Bechtle reception. (main station): Coming from the West (Stuttgart): Take the underground number U4 or U5 to the On the A8/A99 towards Munich, take exit 12a – Odeonsplatz stop and then take the U6 towards München-Neuherberg Garching-Forschungszentrum to the Garching- Continue towards Oberschleißheim on the B13 – Hochbrück stop (marked “U” on the map) Ingolstädter Landstrasse Walk towards Schleißheimer Strasse/B471, After 3.5 km turn right into Schleißheimer cross the street and continue to the roundabout, Strasse/B471 then turn right (approx. -

Spielplan Beginn Liga-Pokal Stand 07-09-2020

Spielplan Meisterschaft und Liga-Pokal Legende: Ligapokal Liga Sa. 19.09.2020 Liga-Po 1 Nordwest Nordost Südwest Viktoria Aschaffenburg - 1. FC Schweinfurt VfB Eichstätt - 1. FC Nürnberg II FV Illertissen - TSV Rain/Lech TSV Aubstadt - SpVgg Greuther Fürth II SpVgg Bayreuth spielfrei FC Memmingen spielfrei Süd Südost VfR Garching - FC Augsburg II SV Wacker Burghausen - TSV Buchbach SV Heimstetten spielfrei SV Schalding-Hein. - TSV 1860 Rosenheim Sa. 26.09.2020 Liga-Po 2 Nordwest Nordost Südwest SpVgg Greut. Fürth II - Viktoria Aschaffenburg SpVgg Bayreuth - VfB Eichstätt FC Memmingen - FV Illertissen 1. FC Schweinfurt - TSV Aubstadt (2) 1. FC Nürnberg II spielfrei TSV Rain spielfrei Süd Südost SV Heimstetten - VfR Garching (3) TSV Buchbach - SV Schalding-Heining FC Augsburg II spielfrei TSV 1860 Rosenheim - SV W. Burghausen Sa. 26.09.2020 Nachhol-SpT 22 Aubstadt - Garching Di. 06.10.2020 Nachhol-SpT Liga-Po Schweinfurt - Aubstadt (2) v. 26.09. Heimstetten - Garching (3) v. 26.09. Burghausen - Schalding (4) v. 03.10. Memmingen - Rain (5) v. 03.10. Sa. 03.10.2020 Nachhol-SpT 14 Nachhol-SpT 23 Garching - Memmingen Schalding - Rain Sa. 03.10.2020 Liga-Po 3 Nordwest Nordost Südwest SpVgg Greuther Fürth II - 1. FC Schweinfurt SpVgg Bayreuth - 1. FC Nürnberg II FC Memmingen -TSV Rain/Lech (5) TSV Aubstadt - SV Viktoria Aschaffenburg VfB Eichstätt spielfrei FV Illertissen spielfrei Süd Südost SV Heimstetten - FC Augsburg II TSV Buchbach - TSV 1860 Rosenheim VfR Garching spielfrei SV W. Burghausen - SV Schalding-H. (4) Sa. 10.10.2020; 26. Spieltag Sa. 17.10.2020, 25. Spieltag Sa. 24.10.2020, 24. -

[email protected], Contact Number: 0032-470-134-495

Creative Cities: How urban transformation and innovation strategies stimulate creativity and entrepreneurship? Practical information package Contacts: EUROCITIES: Aleksandra Olejnik, e-mail: [email protected], contact number: 0032-470-134-495. Munich: Raymond Saller: email address: [email protected]. Munich, the capital of Bavaria, is located in the centre of Europe. The city is well connected by trains, buses and has the second largest airport of Germany. The conference will take place in different venues: Wednesday and Friday next to the Eastern Railway Station (Ostbahnhof). Thursday at the university campus of the Munich Technical University in Garching. By train / By bus The Central Railway Station (Hauptbahnhof) and the Central Bus Station (ZOB) are connected to the Eastern Railway Station by S-Bahn (all suburban train lines, every three minutes). The trip takes approx. 10 minutes. By plane Munich Airport is 50 km far from the city centre. The S8 S-Bahn line connects the airport to the Munich city center at 20-minute intervals. The trip to the Eastern Railway Station (Ostbahnho) takes approx. 30 minutes. The trains pass the Eastern Railway Station, next to the Werksviertel where the EDF-meeting will be opened on Wednesday, 16 October and closed on Friday, 18 October. By taxi Taxi from the airport to the city centre costs appr. 70 EUR. Public Transport Tickets Munich has an extensive public transportation system. It consists of a network of underground (U-Bahn), suburban trains (S-Bahn), trams and buses (map attached). All S-Bahn suburban lines go through the city centre and connect Munich‘s Central Station (Hauptbahnhof) to East Station (Ostbahnhof) with popular tourist destinations like Marienplatz and Karlsplatz in between.