Politically Manipulated Emotions and Representations of the Enemy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

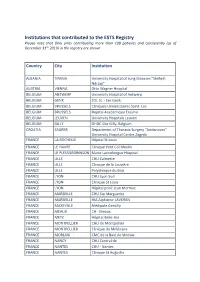

Institutions That Contributed to the ESTS Registry

Institutions that contributed to the ESTS Registry Please note that Only units contributing more than 100 patients and consistently (as of December 31th 2019) in the registry are shown Country City Institution ALBANIA TIRANA University Hospital of Lung Diseases "Shefqet Ndroqi" AUSTRIA VIENNA Otto Wagner Hospital BELGIUM ANTWERP University Hospital of Antwerp BELGIUM GENK ZOL St. - Jan Genk BELGIUM BRUSSELS Cliniques Universitaires Saint- Luc BELGIUM BRUSSELS Hopital Academique Erasme BELGIUM LEUVEN University Hospitals Leuven BELGIUM GILLY GHDC Site Gilly, Belgium CROATIA ZAGREB Department of Thoracic Surgery “Jordanovac” University Hospital Centre Zagreb FRANCE LA ROCHELLE Hôpital St Louis FRANCE LE HAVRE Clinique Petit Col Moulin FRANCE LE PLESSISROBINSON Marie Lannelongue Hospital FRANCE LILLE CHU Calmette FRANCE LILLE Clinique de la Louvière FRANCE LILLE Polyclinique du Bois FRANCE LYON CHU Lyon Sud FRANCE LYON Clinique St Louis FRANCE LYON Hôpital privé Jean Mermoz FRANCE MARSEILLE CHU Ste Marguerite FRANCE MARSEILLE HIA Alphonse LAVERAN FRANCE MAXEVILLE Médipole Gentilly FRANCE MEAUX CH - Meaux FRANCE METZ Hôpital Belle-Isle FRANCE MONTPELLIER CHU de Montpellier FRANCE MONTPELLIER Clinique du Millénaire FRANCE MORLAIX CMC de la Baie de Morlaix FRANCE NANCY CHU Central de FRANCE NANTES CHU - Nantes FRANCE NANTES Clinique St Augustin FRANCE NANTES Nouvelle Clinique Nantaise FRANCE NICE CHU Pasteur FRANCE NICE Clinique Saint Georges FRANCE NIMES Clinique les Franciscaines FRANCE PARIS HEGP FRANCE PARIS Hôtel Dieu FRANCE PARIS IMM -

Studiu Privind Influenţa Tratamentului Asupra Inflamaţiei Bronşice La

Istoria Medicinei J.M.B. nr.1- 2014 Ion Cantacuzino –cercetĂtor Și organizator al sistemului sanitar românesc, omagiat de francezi Ion Cantacuzino-researcher and organizer of the Romanian health system, honored in France As.univ. drd. Florin Leașu1, as.univ. drd. Oana Andreescu1, prof.univ.dr. Cristina Borzan2, prof. univ. dr. Liliana Rogozea1, 1Facultatea de Medicină Generală, Universitatea „Transilvania”, Braşov 2Facultatea de Medicină, UMF Cluj Napoca Autor corespondent: Florin Leașu, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: A remarkable personality of Romanian medical history, by his formation, education and activity in the field of medicine Ion Cantacuzino belongs in equal measure to France and Romania. His involvement and contribution to medical research as well as to sanitary organisation have secured Cantacuzino a well- deserved place in the gallery of both the Romanian medical school founders and the personalities that have honoured the Pasteur Institute of Paris. Key-words: Ion Cantacuzino, history of medicine, Romania-France relationship Contextul dezvoltării colaborării Nicolae Paulescu, Ion Cantacuzino, personalități româno-franceze în domeniul științei în remarcate în domeniile artei sau științei secolul XX europene și chiar universale, personalități care, Așa cum spunea Mihaela Rădulescu: așa cum spunea Nicolae Titulescu „au deschis „atitudinea empatetică a intelectualilor romani României drumul spre dezvoltarea ei culturală, pentru Franța, pentru limba și cultura franceză dar şi calea spre libertate, unire şi independenţă“ -

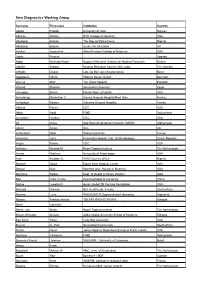

New Diagnostics Working Group

New Diagnostics Working Group Surname First name Institution Country Abebe Fekadu University of Oslo Norway Abrams William NYU College of Dentistry USA Abubakar Aishatu The Nigeria Police Force Nigeria Abubakar Ibrahim Centre for Infections UK Achkar Jacqueline Albert Einstein College of Medicine USA Adatu Francis Uganda Addo Kennedy Kwasi Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research Ghana Adetifa Ifedayo Medical Research Council (UK) Labs. The Gambia Affolabi Dissou Lab. De Ref. des Mycobacteries Benin Aggerbeck Henrik Statens Serum Institut Denmark Ahmed Altaf The Indus Hospital Pakistan Ahmed Shwikar Alexandria University Egypt Ahmedov Sevim Florida Dept. of Health USA Aichelburg Maximilian C. Vienna General Hospital/Med. Univ. Austria Al-Aghbari Nasher Althawra General Hospital Yemen Albalak Rachel CDC USA Albert Heidi FIND Switzerland Alexander Heather CDC USA Ali Imtiaz Aga Khan development Network (AKDN) Afghanistan Alnimr Amani UCL UK Al-Somboli Najla Sanaa University Yemen Amlerova Jana University Hospital, Inst. Of Microbiology Czech Republic Angra Pawan CDC USA Anthony Richard M. Royal Tropical Institute The Netherlands Arentz Matthew University of Washington USA Awe Ayodele O. WHO Country Office Nigeria Banach David Mount Sinai Medical Center USA Banaei Niaz Stanford Univ. School of Medicine USA Banerjee Saibal Dept. of Health & Family Welfare India Bao Fuka (Frank) Kunming Medical University China Barker Lewellys F Aeras Global TB Vaccine Foundation USA Barnard Marinus Nat. Health Lab. Service South Africa Barrera Lucia WHO/IUATLD Supranational Laboratory Argentina Basore Tesfaye Abicho TBCAP/USAID-ETHIOPIA Ethiopia Basri Carmelia Beers, van Stella Royal Tropical Institute The Netherlands Bekele Binegdie Amsalu Addis Ababa University School of Medicine Ethiopia Ben Amor Yanis Columbia University USA Beyers N., Prof. -

Curriculum Vitae Europass

Curriculum vitae Europass Informaţii personale Nume / Prenume TODEA, Doina Adina Adresă(e) Telefon(oane) Fax(uri) E-mail(uri) Naţionalitate(-tăţi) romana Data naşterii Sex feminin Domeniul ocupaţional Cadru didactic in invatamantul superior si asistenta medicala spitaliceasca Experienţa profesională 2016 martie - Hotararea Consiliului Facultatii de Medicina nr 4/2016, Profesor la Disciplina Pneumologie, Departamentul 6 Specialitati Medicale Atestatul de ABILITARE 2015 “Progresses and new approaches in prevention, diagnostic and treatment on noncommunicable diseases, chronic respiratory diseases” Perioada 2003 - 2016 Funcţia sau postul ocupat 1.Conferenţiar universitar Disciplina Pneumologie, Facultatea de Medicină, Universitatea de Medicină şi Farmacie „ Iuliu Haţieganu” Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2.Medic primar pneumolog confirmata prin OMS Nr 694/1998-Secţia Pneumoftiziologie III Spitalul Clinic de Pneumoftiziologie “Leon Daniello” Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2004 – 2013 Director Medical – activitate managerierea medicala la Spitalul Clinic de Pneumologie “Leon Daniello” Cluj Napoca din 2013 iulie si in prezent - Sef sectie Pneumoftiziologie III, Spitalul Clinic de Pneumologie “Leon Daniello” Cluj Napoca 1 Activităţi şi responsabilităţi Activitate didactică: Cursuri de predare pneumoftiziologie pentru studenţii anul IV si V Medicină principale Generală, predare curs şi lucrări practice de Ftiziologie anul IV Facultatea de Asistenti Medicali si Moase si Curs de Bazele Nursing an I pentru studentii de Radiologie Imagistica si Balneofiziokinetoterapie, -

Întâlnirea Secțiuii De Cancer Pulmonar a Srp / Meeting of the Lung

Cel de-al 26-lea CONGRES NAȚIONAL al Societății Române de Pneumologie a fost creditat cu 24 credite EMC de către Colegiul Medicilor din România (pentru medici) și cu 15 credite OAMMR de către Ordinul Asistenților Medicali Generaliști, Moașelor și Asistenților Medicali din România (pentru asistenții medicali). 4 CONGRES NAŢIONAL ) ) al 26-lea al 26-lea al Societatii Române de Pneumologie MESAJUL PREȘEDINTELUI Dragi colegi, Societatea Română de Pneumologie (SRP) are deosebita plăcere de a vă invita în această toamnă la cel mai mare eveniment al său: AL XXVI-LEA CONGRES NAŢIONAL, ce va avea loc în perioada 4-8 noiembrie. Evenimentul se va desfăşura (în premieră!) ONLINE, pe o platformă virtuală pentru care vă vom trimite din timp un link de conectare. Congresul din acest an va fi o experienţă inedită, întrucât veţi putea viziona simpozioane şi cursuri live, la fel de interactive ca şi cele faţă în faţă, veţi putea vizita zona expoziţională, precum şi zona de e-postere, toate acestea din confortul casei sau cabinetului dumneavoastră. Tema centrală a ediţiei de anul acesta a Congresului este Pneumologia: provocări şi inter- disciplinaritate şi, sub umbrela generoasă a acesteia, o serie de alte teme majore vor fi abordate, precum: – infecţiile pulmonare – neoplasmul bronho-pulmonar – tuberculoza pulmonară – bolile obstructive bronho-pulmonare cronice – comorbidități cu implicare pulmonară – afectarea pulmonară în bolile de sistem – explorarea funcţională respiratorie. Al XXVI-lea Congres Naţional al Societăţii Române de Pneumologie este un eveniment ști- ințific cu caracter multidisciplinar care își propune să reunească asociaţii profesionale și spe- cialiști de renume din ţară și din străinătate, reprezentanţi ai tuturor specialităţilor implicate în domeniul bolilor respiratorii, cu scopul de a promova excelența științifică, încurajând expunerea unui spectru larg de lucrări științifice din domeniile abordate. -

United Nations HRI/CORE/ROU/2011

United Nations HRI/CORE/ROU/2011 International Human Rights Distr.: General 10 January 2012 Instruments Original: English Core document forming part of the reports of States parties Romania* ** [12 October 2011] * In accordance with the information transmitted to States parties regarding the processing of their reports, the present document was not formally edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. ** Annex can be consulted in the files of the Secretariat. GE.12-40141 HRI/CORE/ROU/2011 Contents Paragraphs Page I. General information about Romania ....................................................................... 1– 102 3 A. Geographical category .................................................................................... 1–2 3 B. Historical background ..................................................................................... 3–9 3 C. Demographic characteristics ........................................................................... 10–16 4 D. Demographic data ........................................................................................... 17–18 5 E. Social and demographic characteristics .......................................................... 19–60 5 F. Economic characteristics ................................................................................ 61–81 17 G. Political characteristics ................................................................................... 82–93 21 H. Crime statistics and judicial characteristics ................................................... -

Emory University School of Medicine, Director: Sharon W

Curriculum Vitae Octavian C. Ioachimescu, MD, PhD Revised: Dec 15th, 2014 Summary: Staff Physician at Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) and Associate Professor of Medicine at Emory University, with special interests and extensive activity in the fields of (1) Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine – obstructive airway diseases such as asthma, COPD and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), (2) Predictive Health, (3) Medical Education in Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, and (4) Organizational Leadership (as Atlanta VAMC Sleep Medicine Center Medical Director and Sleep Section Chief). 1. Name: Octavian C. Ioachimescu 2. Office Address: Atlanta VA Medical Center (VAMC) Sleep (111) 1670 Clairmont Rd. Decatur, GA 30033 Telephone: 404-321-6111 ext. 7258 (O) 216-346-8175 (C) Fax: 404-417-2903 3. E-mail Address: [email protected] or [email protected] 4. Citizenship: Romanian Citizen; US Permanent Resident 5. Current Titles and Affiliations: a. Academic appointments: 1. Primary appointments: Associate Professor of Medicine, Emory University, School of Medicine, 2013 – present 2. Joint and secondary appointments: Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor of Octavian C. Ioachimescu, MD, PhD - Curriculum Vitae 12/15/2014 Page 1/37 Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, 2009 – present b. Clinical appointments: 1. Medical Director, Sleep Disorders Center, Atlanta VAMC, 2007 – present (renamed in 2013 Sleep Medicine Center) 2. Medical Director, Respiratory Therapy Department, Atlanta VAMC, 2009 - 2012 3. Section Chief, VA Sleep Medicine Section, August 2012 – present c. Education appointments: Emory Sleep Medicine Fellowship VA Site Director and Core Faculty – June 2012 - present 6. Previous Academic and Professional Appointments: Clinical Instructor, Pulmonology, Carol Davila University, Bucharest, Romania, 1998 – 2000 Assistant Professor of Medicine, Emory University, School of Medicine, 2007–2013 7. -

Surveillance of Tuberculosis in Europe - Eurotb

Surveillance of Tuberculosis in Europe - EuroTB Report on tuberculosis cases notified in 1998 Institut de Veille Sanitaire, France WHO Collaborating Centre for the Surveillance of Tuberculosis in Europe Royal Netherlands Tuberculosis Association (KNCV) Surveillance of tuberculosis in Europe: participating countries and national institutions Andorra Ministry of Health and Welfare Andorra la Vella Albania Ministry of Health and Environment Tirana University Hospital of Lung Diseases Tirana Armenia Ministry of Health Yerevan Austria Bundesministerium für soziale Sicherheit und Generationen Vienna Azerbaijan Ministry of Health Baku Belarus Scientific Research Institute of Pneumology and Pthisiology Minsk Belgium Belgium Lung & Tuberculosis Association (BELTA) Brussels Bosnia & Herzegovina Clinic of Pulmonary Diseases and Tuberculosis “Podhrastovi” Sarajevo Public Health Institute Banja Luka Bulgaria Ministry of Health Sofia Croatia Croatian National Institute of Public Health Zagreb Czech Republic Clinic of Chest Diseases & Thoracic Surgery Prague Denmark Statens Serum Institut Copenhagen Estonia Kivimae Hospital Ministry of Health Tallinn Finland National Public Health Institute Helsinki France Direction générale de la Santé Paris Institut de Veille Sanitaire Saint-Maurice Georgia Institute of Phtisiology and Pulmonology Tbilisi Germany Robert Koch-Institut Berlin Greece National Centre for Surveillance and Intervention (NCSI) Athens Hungary “Koranyi” National Institute of Tuberculosis & Pulmonology Budapest Iceland Reykjavik Health Care -

A New Project: a Re-Launch of Strategy

RSP Activity • DOI: 10.2478/pneum-2019-0003 • 68 • 2019 • 46-47 Pneumologia A new project: a re-launch of strategy Florin Mihălțan1,2,†, Ruxandra Ulmeanu1,3, Beatrice Mahler1,2 1Marius Nasta Pneumoftiziology Institute, Bucharest, Romania 2Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania 3Faculty of Medicine, Oradea, Romania The “Marius Nasta” Pneumoftiziology Institute, the National • In 2017, 105 new and recurrent cases of TB were reported Program for the Prevention, Supervision and Control of in the prison penitentiary, which is approximately 7.5 times Tuberculosis in Romania (PNPSCT) and the Romanian higher than the general population (2). Society of Pneumology officially launched on November 20th, 2018, the E-DETECT TB program, the first active tuberculosis The amplitude of the project will allow for the examination of (TB) screening campaign in our country, made through a about 20,000 people within E-DETECT TB with the possibility of mobile medical unit with imaging and molecular diagnostic extending up to 25,000 beneficiaries. The examinations will be equipment. carried out with the help of a mobile medical unit, equipped with E-DETECT TB is a wide-ranging project at the European level in imaging equipment and molecular diagnostics, by specialists countries such as Bulgaria, Italy, Great Britain, the Netherlands, from the Marius Nasta Pneumoftiziology Institute, with the Romania and Sweden with early diagnostics in Romania support of PNPSCT. supported by the National Program for the Supervision and The first step will be to complete a medical questionnaire Fight against Tuberculosis (PNPSCT) and is coordinated by the at the entrance of the person, which will be examined in the “Marius Nasta” Pneumoftiziology Institute in order to ensure the mobile medical unit, and the registration of medical and early, active detection of TB patients. -

Curriculum Vitae Europass

Curriculum vitae Europass Informaţii personale Nume / Prenume DELEANU Oana-Claudia Locul de muncă vizat / Membru in Consiliul Societății Române de Pneumologie Domeniul ocupaţional Experienţa profesională Perioada Ianuarie 2017- Funcţia sau postul ocupat Medic primar pneumolog, expertiza in somnologie Activităţi şi responsabilităţi principale Consultatii medicale, stabilirea terapiilor, urmarire tratamente Companie SOMNOLOG (DOC doctor omnia casuum) Perioada 2017- Funcţia sau postul ocupat Sef lucrari Perioada Februarie 2008- prezent Funcţia sau postul ocupat Asistent universitar Activităţi şi responsabilităţi principale Predare zilnica de lucrari practice la studenti incepand cu februarie 2008 Secretar de comisie pentru examenul de medic specialist – pneumologie Indrumator al unor lucrari de licenta finalizate Prezentari de cazuri clinice ca medic rezident si apoi specialist, indrumarea studentilor si a rezidentilor in vederea realizarii de prezentari de cazuri clinice si lucrari Numele şi adresa angajatorului Universitatea de Medicina si Farmacie “Carol Davila” Strada Dumitru Gerota 19, Bucuresti Tipul activităţii sau sectorul de activitate Sanatate Perioada Ianuarie 2012-prezent Funcţia sau postul ocupat Medic primar Perioada 2007-prezent Funcţia sau postul ocupat Medic specialist Pagina / - Curriculum vitae al Pentru mai multe informaţii despre Europass accesaţi pagina: http://europass.cedefop.europa.eu Deleanu Oana-Claudia © Uniunea Europeană Activităţi şi responsabilităţi principale - Asistenta medicala - Ingrijirea pacientilor - Garzi 1-2/luna (in Institutul de Pneumoftiziologie “Dr. M. Nasta”) - Mai mult de 1000 de studii de somn diagnostice si titrari (APAP si manuale) in laboratorul de somn al Institutului de Pneumoftiziologie « Dr. M. Nasta » Bucuresti si intr-o clinica particulara - Efectuare zilnica de probe functionale respiratorii in cadrul laboratorului de studiu al sectiei Pneumologie III al Institutului de Pneumoftiziologie « Dr. -

Bulletin of the World Health Organization

News Tackling tuberculosis with an all-inclusive approach Dr Lucica Ditiu, newly appointed executive secretary of the Stop TB Partnership, spoke to Sarah Cumberland about the many challenges of dealing with a curable disease that is still a long way from elimination. Q: Why is tuberculosis (TB) still a major cause of death and disability in the world? Dr Lucica Ditiu is the newly appointed executive secretary A: TB is a disease that is perfectly of the Stop TB Partnership, based at the World Health curable with very cost-effective tools, drugs Organization (WHO) in Geneva. She has worked at WHO that are readily available, but we are still since 2000 when she joined as a medical officer for a way from reaching our goals. Last year tuberculosis in Albania and the former Yugoslav Republic there were around 1.7 million deaths due of Macedonia within the disaster and preparedness unit to TB and 9 million new cases diagnosed. of the WHO Regional Office for Europe. A 1992 graduate This is due both to a lack of resources to of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Bucharest, properly address all the gaps, as well as a Courtesy of Lucica Ditiu lack of involvement of all stakeholders and Dr Lucica Ditiu Ditiu completed specialty training in pulmonology through partners to engage at both the global and a joint programme with the Romanian National Institute of local levels. TB still needs better visibility Lung Diseases (Marius Nasta). In 1999, she received a certificate in International and attention. Public Health from George Washington University in Washington, DC, which she completed as a fellow in the epidemiology of lung diseases, TB control and Q: What do you consider is the biggest chal- programme management and evaluation. -

Variation Across Romania in the Health Impact of Increasing Tobacco Taxation

European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 28, Supplement 2, 2018, 10–13 ß World Health Organization, 2018. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO License (https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0/igo/) which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1093/eurpub/cky180 ......................................................................................................... Variation across Romania in the health impact of increasing tobacco taxation Magdalena Ciobanu1, Ionel Iosif2, Cristian Calomfirescu2, Lacramioara Brinduse2, David Stuckler3, Aaron Reeves4, Andrew Snell5, Kristina Mauer-Stender5, Bente Mikkelsen5, Alexandra Cucu2 1 Institutul National de Pneumoftiziologie ‘‘Marius Nasta’’ Bucuresti, Romania 2 Institutul National de Sanatate Publica, Bucuresti, Romania 3 Department of Social and Political Sciences, Universita` Bocconi, Milan, Italy 4 Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, Oxford, England 5 World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe, Copenhagen, Denmark Correspondence: Magdalena Ciobanu, Institutul National de Pneumoftiziologie ‘‘Marius Nasta’’ Bucuresti, Sos. Viilor 90, Sector 5, BucureZti, Romania, Tel: +40213356920, Fax: +40213356920, e-mail: [email protected] Background: Tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death globally and tobacco taxation is a cost-effective method of reducing tobacco use in countries and increasing revenue. However, without adequate enforcement some argue the risk of increasing illicit trade in cheap tobacco makes taxation ineffective. We explore this by testing sub-national variations in the impact of tobacco tax increases from 2009 to 2011, on seven smoking-related diseases in adults in Romania, to see if regions that are prone to cigarette smuggling due to bordering other countries see less benefit.