A Case Study on Hans Reichenbach's Naturalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's Philosophy Frederick Joseph Parker

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1936 The development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy Frederick Joseph Parker Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Frederick Joseph, "The development of Dr. Alfred North Whitehead's philosophy" (1936). Master's Theses. Paper 912. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. mE Dt:VEto!l..mm oa llS. At..~"1lr:D !JG'lt'fR ~!EREAli •a MiILOSO?ll' A. thesis SUbm1tte4 to the Gradus:te i'acnl ty in cana1:.at1: f!Jr tbe degree of llaste,-. of Arts Univerait7 of !llcuor.&a Jnno 1936 PREF!~CE The modern-·wr1 ter in the field of Philosophy no doubt recognises the ilfficulty of gaining an ndequate and impartial hearing from the students of his own generation. It seems that one only becomes great at tbe expense of deatb. The university student is often tempted to close his study of philosophy- after Plato alld Aristotle as if the final word has bean said. The writer of this paper desires to know somethi~g about the contribution of the model~n school of phiiiosophers. He has chosen this particular study because he believes that Dr. \i'hi tehesa bas given a very thoughtful interpretation of the universe .. This paper is in no way a substitute for a first-hand study of the works of Whitehead. -

Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy

Open Journal of Philosophy, 2014, 4, 231-243 Published Online August 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojpp http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2014.43031 Philosophical Theory-Construction and the Self-Image of Philosophy Niels Skovgaard Olsen Department of Philosophy, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany Email: [email protected] Received 25 May 2014; revised 28 June 2014; accepted 10 July 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract This article takes its point of departure in a criticism of the views on meta-philosophy of P.M.S. Hacker for being too dismissive of the possibility of philosophical theory-construction. But its real aim is to put forward an explanatory hypothesis for the lack of a body of established truths and universal research programs in philosophy along with the outline of a positive account of what philosophical theories are and of how to assess them. A corollary of the present account is that it allows us to account for the objective dimension of philosophical discourse without taking re- course to the problematic idea of there being worldly facts that function as truth-makers for phi- losophical claims. Keywords Meta-Philosophy, Hacker, Williamson, Philosophical Theories 1. Introduction The aim of this article is to use a critical discussion of the self-image of philosophy presented by P. M. S. Hacker as a platform for presenting an alternative, which offers an account of how to think about the purpose and cha- racter of philosophical theories. -

Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholarship@Western Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-23-2015 12:00 AM Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought Ben Woodard The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Tilottama Rajan The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Joan Steigerwald The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Theory and Criticism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Ben Woodard 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Woodard, Ben, "Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3314. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3314 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schelling's Naturalism: Motion, Space, and the Volition of Thought (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Benjamin Graham Woodard A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Theory and Criticism The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ben Woodard 2015 Abstract: This dissertation examines F.W.J. von Schelling's Philosophy of Nature (or Naturphilosophie) as a form of early, and transcendentally expansive, naturalism that is, simultaneously, a naturalized transcendentalism. -

On Natural Causes: Implications for a Teleological View of the World

ON NATURAL CAUSES Implications for a teleological view of the world Joseph D. Renick1 March 15, 2020 Methodological naturalism is a guiding principle imposed on scientific methodology that limits science to the consideration of natural causes alone where “natural causes” explicitly means “non- supernatural causes”. Its principle role is to protect the teaching of biological evolution in public schools from challenges to its veracity posed by evidence of design in nature where, under the scrutiny of methodological naturalism, all such evidence is labelled “religion, not science”. However, an objective consideration of the reasoning involved in scientific methodology leads to the conclusion that the meaning of “natural causes” should be based on what a natural cause is, not on what it is not. This observation surprisingly leads to the proposition that both law and design must be viewed as natural causes. Further, it is evident that law and design are unified in nature and if they are unified in nature, they must also be unified in the natural sciences. This leads to the proposition that if law and design are unified in the natural sciences, they must also be unified in science education in public schools. We conclude that methodological naturalism has a legitimate role in its oversight of the methods of science, but that oversight must be limited to the methods themselves, not the metaphysical implications that might arise as a result of those methods. Otherwise, methodological naturalism functions as metaphysical naturalism. Methodological naturalism is a guiding principle imposed on scientific methodology that limits science to the consideration of natural causes alone. -

John Stamos Helps Inspire Youngsters on WE

August 10 - 16, 2018 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad John Stamos H K M F E D A J O M I Z A G U 2 x 3" ad W I X I D I M A G G I O I R M helps inspire A N B W S F O I L A R B X O M Y G L E H A D R A N X I L E P 2 x 3.5" ad C Z O S X S D A C D O R K N O youngsters I O C T U T B V K R M E A I V J G V Q A J A X E E Y D E N A B A L U C I L Z J N N A C G X on WE Day R L C D D B L A B A T E L F O U M S O R C S C L E B U C R K P G O Z B E J M D F A K R F A F A X O N S A G G B X N L E M L J Z U Q E O P R I N C E S S John Stamos is O M A F R A K N S D R Z N E O A N R D S O R C E R I O V A H the host of the “Disenchantment” on Netflix yearly WE Day Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bean (Abbi) Jacobson Princess special, which Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Luci (Eric) Andre Dreamland ABC presents Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Elfo (Nat) Faxon Misadventures King Zog (John) DiMaggio Oddballs 1 x 4" ad Friday. -

God As Both Ideal and Real Being in the Aristotelian Metaphysics

God As Both Ideal and Real Being In the Aristotelian Metaphysics Martin J. Henn St. Mary College Aristotle asserts in Metaphysics r, 1003a21ff. that "there exists a science which theorizes on Being insofar as Being, and on those attributes which belong to it in virtue of its own nature."' In order that we may discover the nature of Being Aristotle tells us that we must first recognize that the term "Being" is spoken in many ways, but always in relation to a certain unitary nature, and not homonymously (cf. Met. r, 1003a33-4). Beings share the same name "eovta," yet they are not homonyms, for their Being is one and the same, not manifold and diverse. Nor are beings synonyms, for synonymy is sameness of name among things belonging to the same genus (as, say, a man and an ox are both called "animal"), and Being is no genus. Furthermore, synonyms are things sharing a common intrinsic nature. But things are called "beings" precisely because they share a common relation to some one extrinsic nature. Thus, beings are neither homonyms nor synonyms, yet their core essence, i.e. their Being as such, is one and the same. Thus, the unitary Being of beings must rest in some unifying nature extrinsic to their respective specific essences. Aristotle's dialectical investigations into Being eventually lead us to this extrinsic nature in Book A, i.e. to God, the primary Essence beyond all specific essences. In the pre-lambda books of the Metaphysics, however, this extrinsic nature remains very much up for grabs. -

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

The Encounter Between Naturalistic Atheism and Christian Theism

Michael Peterson The Encounter Between Naturalistic Atheism and Christian Theism Michael Peterson (b. 1950) sets the debate between atheism and theism in the larger context of a worldview conflict between naturalism, which entails atheism, and Christian belief, which entails theism. He tries to show that Christian theism has intellectual resources that can handle both arguments against theism and arguments for atheism. Then he compares the capacity of atheistic naturalism and Christian theism to generate credible explanations of many important features of reality, such as consciousness, mind, morality, and personhood. He concludes that such impressive phenomena are not likely to occur in a naturalistic universe and that naturalists provide explanations of them that are reductionistic and strained. However, in a universe described by Trinitarian Christian theism, which was cre ated by a supremely intelligent, moral, personal, and relational being, it is much more likely that finite consciousness, mind, morality, and personhood would arise. n academia and broader society, the intellectual of reality. An explanation of everything is a I conflict between theism and atheism continues. worldview-a comprehensive conceptual frame Theism is the belief that an omnipotent, omniscient, work that makes sense of important features of life and perfectly good personal spiritual being exists and the world. Both theists and atheists advance who is creator and sustainer of the universe; this key arguments and cite significant evidence for being is designated God. Positive atheism is the their positions. Thorough worldview assessment belief that God does not exist, i.e., the denial of must evaluate all of the arguments, pro and con, theism. -

Existence in Physics

Existence in Physics Armin Nikkhah Shirazi ∗ University of Michigan, Department of Physics, Ann Arbor January 24, 2019 Abstract This is the second in a two-part series of papers which re-interprets relativistic length contraction and time dilation in terms of concepts argued to be more fundamental, broadly construed to mean: concepts which point to the next paradigm. After refining the concept of existence to duration of existence in spacetime, this paper introduces a criterion for physi- cal existence in spacetime and then re-interprets time dilation in terms of the concept of the abatement of an object’s duration of existence in a given time interval, denoted as ontochronic abatement. Ontochronic abatement (1) focuses attention on two fundamental spacetime prin- ciples the significance of which is unappreciated under the current paradigm, (2) clarifies the state of existence of speed-of-light objects, and (3) leads to the recognition that physical existence is an equivalence relation by absolute dimensionality. These results may be used to justify the incorporation of the physics-based study of existence into physics as physical ontology. Keywords: Existence criterion, spacetime ontic function, ontochronic abatement, invariance of ontic value, isodimensionality, ontic equivalence class, areatime, physical ontology 1 Introduction This is the second in a two-part series of papers which re-interprets relativistic length contraction and time dilation in terms of concepts argued to be more fundamental, broadly construed to mean: concepts which point to the next paradigm. The first paper re-conceptualized relativistic length contraction in terms of dimensional abatement [1], and this paper will re-conceptualize relativistic time dilation in terms of what I will call ontochronic abatement, to be defined as the abatement of an object’s duration of existence within a given time interval. -

CAUSATION Chapter 4 Humean Reductionism

CAUSATION Chapter 4 Humean Reductionism – Analyses in Terms of Nomological Conditions Many different accounts of causation, of a Humean reductionist sort, have been advanced, but four types are especially important. Of these, three involve analytical reductionism. First, there are approaches which start out from the general notion of a law of nature, then define the ideas of necessary, and sufficient, nomological conditions, and, finally, employ the latter concepts to explain what it is for one state of affairs to cause another. Secondly, there are approaches that employ subjunctive conditionals, either in an attempt to give a purely counterfactual analysis of causation (David Lewis, 1973 and 1979), or as a supplement to other notions, such as that of agency (Georg von Wright, 1971). Thirdly, there are approaches that employ the idea of probability, either to formulate a purely probabilistic analysis (Hans Reichenbach, 1956; I. J. Good, 1961 and 1962; Patrick Suppes, 1970; Ellery Eells, 1991; D. H. Mellor, 1995) - where the central idea is that a cause must, in some way, make its effect more likely -- or as a supplement to other ideas, such as that of a continuous process (Wesley Salmon, 1984). Finally, a fourth approach involves the idea of offering, not an analytic reduction of causation, but a contingent identification of causation, as it is in this world, with a relation whose only constituents are non- causal properties and relations. One idea, for example, is that causal processes can be identified with continuous processes in which relevant quantities are conserved (Wesley Salmon, 1997 and 1998; Phil Dowe, 2000a and 2000b). -

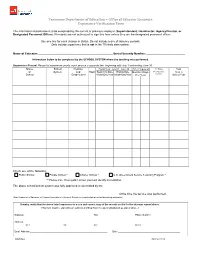

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

Bringing Nature to Light: Schellingâ•Žs Naturphilosophie in the Early

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 1-1-2013 Bringing Nature to Light: Schelling’s Naturphilosophie in the Early System of Identity Michael Vater Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Analecta Hermeneutica, Vol. 5 (2013). Permalink. © 2013 International Institute for Hermeneutics. Used with permission. ISSN 1918-7351 Volume 5 (2013) Bringing Nature to Light: Schelling’s Naturphilosophie in the Early System of Identity Michael Vater Light is already a completely ideal activity that deconstructs and reconstructs objects just as the light of idealism always does— and so Naturphilosophie provides a physical explanation of idealism, which proves that at the boundaries of nature there must break forth the intelligence we see break forth in the guise of humanity [Person des Menschen]. Schelling, General Deduction of Dynamic Process, § 631 In November of 1800 the issue of the reality of nature and its meaning for a transcendental philosophy interrupts, or rather heats up, the exchange of letters between Fichte in Berlin and Schelling in Jena. Fichte has faint praise for the latter‟s System of Transcendental Idealism and marks as problematic the way it sets nature alongside of consciousness as the subject of a genetic deduction. For transcendental philosophy, he insists, nature can only be something found, finished, perfect because lawful, but whose lawfulness is not its own, but that of the intelligence which beholds and explains.2 Schelling responds with a long recital of his philosophical development and poses several alternative ways that philosophy of nature might coincide with Wissenschaftslehre, the most radical of which suggests that philosophy of consciousness must be based on natural philosophy, not the reverse.