AAIB Bulletin 7-2015.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SL2016-634: Ridge Wear at Crankpin Journals

Service Letter SL2016-634/JNN Action code: WHEN CONVENIENT Ridge Wear at Crankpin Journals SL2016-634/JNN November 2016 Dear Sirs Concerns This service letter contains important information about the develop- Owners and operators of ment of ridge wear at the crankshaft journal and the precautions re- MAN four-stroke diesel engines. quired in connection with the replacement of connecting rod bearings. Type: If the ridge is not addressed, this may cause severe engine damage GenSets: L16/24(S), L21/31(S), with a possible loss of property and life. L27/38(S), L23/30H/DF, L23/30S, Ridge wear will inevitably develop over time at the crank pin journal. L28/32H/DF, L28/32S, V28/32H, The wear pattern is caused by abrasive impurities that remain in the V28/32S lube oil. Efficient lube oil cleaning is therefore essential to keep the Propulsion: L21/31, L27/38, L23/30(A), development of ridge wear as low as possible in trunk engines. V23/30(A), L28/32(A), V28/32(A) If you have any questions or comments, please forward your email to [email protected] with reference to this service letter. Yours faithfully Mikael C. Jensen Jørgen Paaske Nielsen Vice President Superintendent Engineer Engineering Operation MAN Diesel & Turbo MAN Diesel & Turbo MAN Diesel & Turbo H. Christoffersensvej 6 Niels Juels Vej 15 Branch of MAN Diesel & Turbo SE, 4960 Holeby 9900 Frederikshavn Germany Denmark Denmark CVR No.: 31611792 Phone: +45 54 69 31 00 Phone: +45 96 20 41 00 Head office: Teglholmsgade 41 Fax: +45 54 69 30 30 Fax: +45 96 20 40 30 2450 Copenhagen SV, Denmark [email protected] [email protected] German Reg.No.: HRB 22056 Amtsgericht Augsburg www.mandieselturbo.com Service Letter SL2016-634/JNN Ridge wear will inevitably develop over time at the crank pin journal. -

DNVGL-CG-0037 Calculation of Crankshafts for Reciprocating

CLASS GUIDELINE DNVGL-CG-0037 Edition November 2015 Calculation of crankshafts for reciprocating internal combustion engines The electronic pdf version of this document, available free of charge from http://www.dnvgl.com, is the officially binding version. DNV GL AS FOREWORD DNV GL class guidelines contain methods, technical requirements, principles and acceptance criteria related to classed objects as referred to from the rules. © DNV GL AS November 2015 Any comments may be sent by e-mail to [email protected] If any person suffers loss or damage which is proved to have been caused by any negligent act or omission of DNV GL, then DNV GL shall pay compensation to such person for his proved direct loss or damage. However, the compensation shall not exceed an amount equal to ten times the fee charged for the service in question, provided that the maximum compensation shall never exceed USD 2 million. In this provision "DNV GL" shall mean DNV GL AS, its direct and indirect owners as well as all its affiliates, subsidiaries, directors, officers, employees, agents and any other acting on behalf of DNV GL. CHANGES – CURRENT This is a new document. Editorial corrections In addition to the above stated main changes, editorial corrections may have been made. Changes - current Class guideline — DNVGL-CG-0037. Edition November 2015 Page 3 Calculation of crankshafts for reciprocating internal combustion engines DNV GL AS CONTENTS Changes – current...................................................................................................... 3 -

DUMS I{ATIONALADVISORY COMMITTEE for AERONAUTICS

,- TECHN1CAL MEMO.RAI?DUMS i{ATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR AERONAUTICS. No. 309 —. LIGHT AEROPLANE ENGINE DEVELOPIM1lT. ... By Lieut. -Col. L. F. R, Fell. (Paper read at a joint meeting of the Royal Aeronautical Society and of the In8tit~~tion of Au_kornobileEngineersj February 19, 1925.) ..,’ —.—->... ,.. ,, April, 1925. —- .-— — 31176014410519 “LIGHT AEROPLANZ ENGINE.D~EIJOp~JE]TT~* ByLieut.-Col.-F ..F. R. Fell. It has frequently been stated and written that in order to popularize li,ght aircraft the”first essential is the production of a reliable engine capable of being easily maintained and.h,av- ing a long lif~, at the same time selling at a low figure. In the first part of this lecture it” is desired to point out the difficulties in the way of realizing this ideal before re~krking on the claims of the various types for adoption. Difficulties in the way of the Production of Light Aircraft Engines In the first place the public, and even aircraft designers, have been misled as to the t-ypeof engine that”is required by statements made in the nontechnical and sclilitcchnicalPress to the effect that it is possible to fly an aeroplane satisfactorily with a motorcycle engine. At this stage it is desired to state quite definitely that this is’impossible, as figures, which will be given later, cl-earlyindicate. T’nemethod of rating on capacity, instead of on a “~. basis - the normal manner for aircraft engines - has also caused—. consid- * Paper read at a joint mcetingof the Roycl Aeronautical Society and of the Institution of--ktomobile Engineers, February N, 19250 .— .-— .... -

Crankpin Bearings in High Output Aircraft Piston Engines the Evolution of Their Design and Loading by Robert J

Crankpin Bearings in High Output Aircraft Piston Engines The Evolution of their Design and Loading by Robert J. Raymond July 2015 Abstract powered truck. There you will invariably find a 6-cylinder, 4-stroke cycle, open chamber, turbocharged, aftercooled The development of the crankpin bearing in high output engine with electronically controlled fuel injection. Gone are aircraft piston engines is traced over the period 1915-1950 in the two-stroke cycle, divided combustion chambers, and the a large number of liquid and air cooled engines of both many variants of mechanical injection systems found in American and European origin. The changes in bearing truck engines of the past. dimensions are characterized as dimensionless ratios and At the end of the large piston engine era there was still a the resulting changes in the associated weights of rotating broad spectrum of engine configurations being produced and reciprocating parts as weight densities at the crankpin. and actively developed. Along with the major division Bearing materials and developments are presented to indi- between liquid and air-cooled engines there was a turbo- cate how they accommodated increasing bearing loads. compounded engine, a four-row air-cooled radial engine, Bearing loads are characterized by maximum unit bearing engines with poppet valves and engines with sleeve valves, pressure and minimum oil film thickness and plotted as a all in production. There were also a two-stroke turbo-com- function of time. Most of the data was obtained from the lit- pounded Diesel engine, a 2-stroke spark ignition sleeve erature but some results were calculated by the author. -

Engine Driven CHAMPION | ENGINE DRIVEN

9.1–22.5 HP | RECIPROCATING AIR COMPRESSORS Engine Driven CHAMPION | ENGINE DRIVEN Service trucks, contractors, and farmers all need a reliable compressor that will be suitable for the tools they will use. 2 A Winning Combination Champion is the leader in manufacturing dependable compressed air systems. Champion offers a complete line of engine driven compressor packages from 9.1–22.5 HP to meet any application. With an engine driven package there is no need to worry about electrical service. Engine driven air compressors are designed to provide compressed air in remote locations or for emergency production line needs. Champion is committed to delivering superior products built with the exceptional standards you expect from Champion. 3 R & PL-Series Design Features 1 Engine 4 High Mounted 8 Top Plate Design Comprehensive gas or diesel Pressure Gauge Extra clearance allows an engine offering with sizes from Easy to read and reduces the abundant amount of room 9.1–22.5 HP. risk of damage. for hands and tools when servicing. 2 Flexible Oil Drain Hose 5 Simple Mounting Feet Clean services without messy One piece design for easy 9 Pilot Unloader Valve oil spills. mounting. No more draining the tank pressure from job site to job site. With a simple flip of the 3 Belt Tensioning 6 Precise Throttle Control valve, the package can be System with Designed to provide accurate started with a fully pressurized load control and easy starting. Engine Slide Base tank. Provides easy service adjustments to the drive belt. 7 Industrial Duty 10 Legendary The base plate also provides Cogged V-Belts Compressor Pumps a sturdy platform to assist in Provides maximum reliability Utilizes the R & PL Series vibration reduction. -

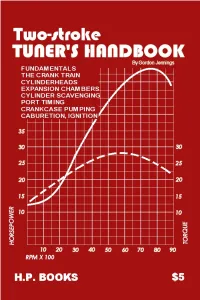

Jennings: Two-Stroke Tuner's Handbook

Two-Stroke TUNER’S HANDBOOK By Gordon Jennings Illustrations by the author Copyright © 1973 by Gordon Jennings Compiled for reprint © 2007 by Ken i PREFACE Many years have passed since Gordon Jennings first published this manual. Its 2007 and although there have been huge technological changes the basics are still the basics. There is a huge interest in vintage snowmobiles and their “simple” two stroke power plants of yesteryear. There is a wealth of knowledge contained in this manual. Let’s journey back to 1973 and read the book that was the two stroke bible of that era. Decades have passed since I hung around with John and Jim. John and I worked for the same corporation and I found a 500 triple Kawasaki for him at a reasonable price. He converted it into a drag bike, modified the engine completely and added mikuni carbs and tuned pipes. John borrowed Jim’s copy of the ‘Two Stoke Tuner’s Handbook” and used it and tips from “Fast by Gast” to create one fast bike. John kept his 500 until he retired and moved to the coast in 2005. The whereabouts of Wild Jim, his 750 Kawasaki drag bike and the only copy of ‘Two Stoke Tuner’s Handbook” that I have ever seen is a complete mystery. I recently acquired a 1980 Polaris TXL and am digging into the inner workings of the engine. I wanted a copy of this manual but wasn’t willing to wait for a copy to show up on EBay. Happily, a search of the internet finally hit on a Word version of the manual. -

Owners Manual

Owners Manual S&S® KN, P, and SH-Series Engines DISCLAIMER: • Consult an appropriate service manual for your motorcycle for correct S&S parts are designed for high performance, closed course, racing applications disassembly and reassembly procedures for any parts that need to be removed and are intended for the very experienced rider only. The installation of S&S parts to facilitate installation. may void or adversely effect your factory warranty. In addition such installation and • Use good judgment when performing installation and operating motorcycle. use may violate certain federal, state, and local laws, rules and ordinances as well Good judgment begins with a clear head. Don’t let alcohol, drugs or fatigue as other laws when used on motor vehicles used on public highways, especially in impair your judgment. Start installation when you are fresh. states where pollution laws may apply. Always check federal, state, and local laws before modifying your motorcycle. It is the sole and exclusive responsibility of the • Be sure all federal, state and local laws are obeyed with the installation. user to determine the suitability of the product for his or her use, and the user shall • For optimum performance and safety and to minimize potential damage to assume all legal, personal injury risk and liability and all other obligations, duties, carb or other components, use all mounting hardware that is provided and and risks associated therewith. follow all installation instructions. The words Harley®, Harley-Davidson®, H-D®, Sportster®, Evolution®, and all H-D Motorcycle exhaust fumes are toxic and poisonous and must not be breathed. -

FINAL PROJECT “Design a Radial Engine”

FINAL PROJECT “Design a Radial Engine” Project and Engineering Department Student: Maxim Tsankov Vasilev Tutors: Dr. Pedro Villanueva Roldan Dk. Pamplona, 27.07.2011 1 Contents I. Radial Engine ................................................................................................................................ 5 II. History of the Radial Engine ........................................................................................................... 7 III. Radial engines nowadays ......................................................................................................... 15 I. Kinematical and Dynamical Calculations ..................................................................................... 18 1. Ratio .............................................................................................................................................. 18 2. Angular velocity ............................................................................................................................ 18 3. Current Piston Stroke ................................................................................................................... 18 4. Area of the piston head: ............................................................................................................... 21 5. Different forces acting on the master-rod: .................................................................................. 21 II. Strength calculations of some of the major parts of the engine................................................ -

Master of Engineering Thesis Modelling a Novel Orbital Ic

Department of Mechanical Engineering University of Canterbury Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha Telephone: +64-3-366 7001 Private Bag 4800 Facsimile: +64-3-364 2078 Christchurch 8020, New Zealand Website: www.mech.canterbury.ac.nz MASTER OF ENGINEERING THESIS MODELLING A NOVEL ORBITAL IC ENGINE TO AID FURTHER DESIGN By Lindsay Muir BE (Hons) 31 August 2014 Requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ENGINEERING IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING Approved by: Dr Dirk Pons, Project Supervisor 1 COPYRIGHT LINDSAY MUIR 24/10/2015 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 11 1.1 Scenario ............................................................................................................. 11 1.2 Purpose .............................................................................................................. 13 1.3 Scope ................................................................................................................. 14 2 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 15 2.1 The Radial and Rotary engine .......................................................................... 15 2.1.1 History ............................................................................................................. 15 2.1.2 Multi-row radials .............................................................................................. 18 2.1.3 Diesel radials ................................................................................................. -

Valve Timing Events and the Order of Importance by Rick Kertes, Technical Contributor [email protected]

Round and Round Camshafts Valve Timing Events and the Order of Importance By Rick Kertes, Technical Contributor [email protected] Roller lifters can handle steeper cam lobe ramps than flat tappet f you’ll recall, in the January tailored in several ways. Option cams. A faster opening and closing issue, we got into the nitty one is duration can be added or rate increases airflow and power. Igritty details of what makes subtracted. If duration is added to a camshaft the “right” camshaft. the lobe the valve is opened and is debatable, somewhat). In this issue, we’ll continue the closed later. Conversely, removing 1. Intake valve closing (IVC) education. Cam class is back in duration delivers inverse results. 2. Intake valve opening (IVO) session! The other method is advancing 3. Exhaust valve closing (EVC) Remember the camshaft makes or retarding the camshaft. 4. Exhaust valve opening (EVO) one complete revolution (360°) Advancing the cam lobe opens while the crankshaft rotates twice and closes the valve earlier while The Intake Lobe (720°) for a complete engine retarding the lobe produces the You will notice that the intake valve cycle. Camshaft timing is usually opposite occurrence. Adding events are placed in the first two expressed in crankshaft degrees duration and moving the lobe in positions of importance. Intake relative to piston location in the one direction or the other preserves events tend to be less forgiving to cylinder, corresponding to TDC the original opening or closing change than exhaust events. Even and BDC. This means that the four at the same time applying the small changes in engine design can piston strokes that occur during added duration on the opposite have serious effects. -

3.4L (DOHC) Engine Mechanical Specifications

60DegreeV6.com 3.4L (DOHC) Engine Mechanical Specifications Millimeters Inches Application General Data Engine Type -- 60° V-6 Displacement -- 240 Cu In Liter (VIN) -- 3.4 (X) RPO -- LQ1 Bore 92 3.622 Stroke 84 3.307 Deck Height 224 8.818 Compression Ratio -- 9.50:1 Firing Order -- 1-2-3-4-5-6 Oil Pressure @ Operating 103 kPa @ 1100 RPM 15 psi min @ 1100 RPM Temperature Cylinder Bore Diameter 92.020-92.038 3.6228-3.6235 Out Of Round Maximum 0.010 0.0004 Taper -- Thrust Side Maximum 0.013 0.00051 Center Distance 111.76 4.4 Piston Diameter-gauged at skirt 91.985-92.000 3.6215-3.6220 10.44 mm (0.413 in) below centerline of piston pin bore Clearance 0.020-0.052 0.0008-0.0020 Pin Bore 23.003-23.010 0.9056-0.9059 Piston Ring Compression Groove 0.033-0.079 0.0013-0.0031 Clearance 1st and 2nd Gap (at gauge diameter) 1st 0.20-0.45 0.008-0.018 1 60DegreeV6.com Gap (at gauge diameter) 2nd 0.56-0.81 0.022-0.032 Oil Groove Clearance 0.028-0.206 0.0011-0.0081 Gap (segment at gauge 0.25-0.76 0.0098-0.0299 diameter) Tension 1st 27.6 N 6.2 lbs Tension 2nd 19.8 N 4.5 lbs Tension Oil 31.2 N 7.0 lbs Piston Pin Diameter 22.9915-22.9964 0.9052-0.9054 Clearance 0.0066-0.0185 0.00026-0.00073 Fit In Rod 0.0165-0.0464 0.0006-0.0018 Crankshaft Main Journal Diameter-All 67.239-67.257 2.6472-2.6479 Taper-Maximum 0.005 0.0002 Out Of Round-Maximum 0.005 0.0002 Cylinder Block Main Bearing 72.155-72.168 2.8407-2.8412 Bore Diameter Crankshaft Main Bearing Inner 67.289-67.316 2.6492-2.6502 Diameter Main Bearing Clearance 0.019-0.064 0.0008-0.0025 Main Thrust Bearing Clearance -

Not-So-Plain Bearings There’S a Lot More to Engine Bearings Than Meets the Eye

MIKE BUSCH COMMENTARY / SAVVY AVIATOR Not-So-Plain Bearings There’s a lot more to engine bearings than meets the eye ACCORDING TO MERRIAM-WEBSTER, a bearing is “a machine part in swings. That’s why nearly all reciprocating which another part turns.” Most aircraft have lots of them. engines—from one-cylinder motorcycle Wheels spin on their axles with the help of tapered roller bear- engines to giant marine diesels—use plain ings. Magnetos, alternators, generators, and starter motors bearings instead of ball or roller bearings. incorporate ball bearings to support their rotors. The landing gear These plain bearings and bushings look trunnions on my Cessna 310 pivot on needle bearings. Variable-pitch simple, but they aren’t. There’s a lot more to propeller blades are supported by large-diameter ball bearings. them than meets the eye. Turbine engine rotor shafts spin in ball and roller bearings. All these bearings consist of inner and outer “races” with spherical or cylin- LUBRICATION drical rolling elements between them. Such “rolling-element When I had the engines in my Cessna 310 bearings” do a superb job of supporting a shaft in precise position torn down for overhaul in 1990, I made a while permitting it to rotate with very little friction. point of paying a visit to the engine shop to But tear down a Continental or Lycoming engine and you won’t survey the damage before the engine was fi nd bearings like those. The bearings in which the crankshaft, crank- put back together. The engines had accumu- pins, camshaft, rocker shafts, and piston pins run have no races, balls, lated 1,900 hours over 11 years, and I rollers, needles, or other moving parts.