Water Level and Wave Height Estimates at NOAA Tide Stations from Acoustic and Microwave Sensors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Body Temperature & Pressure, Saturated” & Ambient Pressure Correction in Air Medical Transport

“Body Temperature & Pressure, Saturated” & Ambient Pressure Correction in air medical transport Mechanical ventilation can be especially challenging during air medical transport, particularly due to the impact of varying atmospheric pressure with changing altitudes. The Oxylog® 3000 plus and Oxylog® 2000 plus help to effectively deal with these challenges. D-33481-2011 Artificial ventilation uses compressed the ventilation volumes delivered by the gas to deliver the required volume to the ventilator. Mechanical ventilation in fixed patient. This breathing gas has normally wing aircraft without a pressurized cabin an ambient temperature level and is very is subject to the same dynamics. In case dry. Inside the human lungs the gas of a pressurized cabin it is still relevant expands due to a higher temperature and to correct the inspiratory volumes, as humidity level. These physical conditions the cabin is usually maintained at MT-5809-2008 are described as “Body Temperature & a pressure of approximately 800 mbar Figure 1: Oxylog® 3000 plus Pressure, Saturated” (BTPS), which (600 mmHg), comparable to an altitude The Oxylog® 3000 plus automatically com- presumes the combined environmental of 8,200 ft/2,500 m. pensates volume delivery and measurement circumstances of – Without BTPS correction, the deli- – a body temperature of 37 °C / 99 °F vered inspiratory volume can deviate up – ambient barometrical pressure to 14 % conditions and (at 14,800 ft/4,500 m altitude) from – breathing gas saturated with water the targeted set volume (i.e. 570 ml vapour (= 100 % relative humidity). instead of 500 ml). – Without ambient pressure correction, Aside from the challenge of changing the inspiratory volume can deviate up temperatures and humidity inside the to 44 % (at 14,800 ft/4,500 m altitude) patient lungs, the ambient pressure is from the targeted set volume also important to consider. -

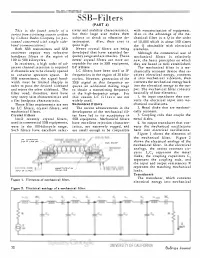

SSB-Filters (PART 4)

--------- ELECTRONICS --------------------- SSB-FilterS (PART 4) ELECTRONICS This is the fourth article of a tivity and stability characteristics, with mtmaturization of equipment. This is the fourth article of a series from a training course written but their large size makes them Also to the advantage of the me series from a training course written by Collins Radio Company for per subject to shock or vibration de· chanical filter is a Q in the order by Collins Radio Company for per- sonnel concerned with single side terioration. Also, their cost is of 10,000 which is about 100 times sonnel concerned with single side- band communications. quite high. the Q obtainable with electrical band communications. Both SSB transmitters and SSB Newer crystal filters are being elements. Both SSB transmitters and SSB developed that have extended fre receivers require very selective receivers require very selective Although the commercial use of bandpass filters in the region of bandpass filters in the region of quency range and are smaller. These mechanical filters is relatively 100 to 500 kilocycles. 100 to 500 kilocycles. newer crystal filters are more ac new, the basic principles on which In receivers, a high order of ad- In receivers, a high order of ad ceptable for use in SSB equipment. they are based is well established. jacent channel rejection is required jacent channel rejection is required LC Filters The mechanical filter is a me if channels are to be closely spaced if channels are to be closely spaced LC filters have been used at IF chanically resonant device that re to conserve spectrum space. -

Part II-1 Water Wave Mechanics

Chapter 1 EM 1110-2-1100 WATER WAVE MECHANICS (Part II) 1 August 2008 (Change 2) Table of Contents Page II-1-1. Introduction ............................................................II-1-1 II-1-2. Regular Waves .........................................................II-1-3 a. Introduction ...........................................................II-1-3 b. Definition of wave parameters .............................................II-1-4 c. Linear wave theory ......................................................II-1-5 (1) Introduction .......................................................II-1-5 (2) Wave celerity, length, and period.......................................II-1-6 (3) The sinusoidal wave profile...........................................II-1-9 (4) Some useful functions ...............................................II-1-9 (5) Local fluid velocities and accelerations .................................II-1-12 (6) Water particle displacements .........................................II-1-13 (7) Subsurface pressure ................................................II-1-21 (8) Group velocity ....................................................II-1-22 (9) Wave energy and power.............................................II-1-26 (10)Summary of linear wave theory.......................................II-1-29 d. Nonlinear wave theories .................................................II-1-30 (1) Introduction ......................................................II-1-30 (2) Stokes finite-amplitude wave theory ...................................II-1-32 -

Waves and Weather

Waves and Weather 1. Where do waves come from? 2. What storms produce good surfing waves? 3. Where do these storms frequently form? 4. Where are the good areas for receiving swells? Where do waves come from? ==> Wind! Any two fluids (with different density) moving at different speeds can produce waves. In our case, air is one fluid and the water is the other. • Start with perfectly glassy conditions (no waves) and no wind. • As wind starts, will first get very small capillary waves (ripples). • Once ripples form, now wind can push against the surface and waves can grow faster. Within Wave Source Region: - all wavelengths and heights mixed together - looks like washing machine ("Victory at Sea") But this is what we want our surfing waves to look like: How do we get from this To this ???? DISPERSION !! In deep water, wave speed (celerity) c= gT/2π Long period waves travel faster. Short period waves travel slower Waves begin to separate as they move away from generation area ===> This is Dispersion How Big Will the Waves Get? Height and Period of waves depends primarily on: - Wind speed - Duration (how long the wind blows over the waves) - Fetch (distance that wind blows over the waves) "SMB" Tables How Big Will the Waves Get? Assume Duration = 24 hours Fetch Length = 500 miles Significant Significant Wind Speed Wave Height Wave Period 10 mph 2 ft 3.5 sec 20 mph 6 ft 5.5 sec 30 mph 12 ft 7.5 sec 40 mph 19 ft 10.0 sec 50 mph 27 ft 11.5 sec 60 mph 35 ft 13.0 sec Wave height will decay as waves move away from source region!!! Map of Mean Wind -

Hurricane Waves in the Ocean

WAVE-INDUCED SURGES DURING HURRICANE OPAL Chung-Sheng Wu*, Arthur A. Taylor, Jye Chen and Wilson A. Shaffer Meteorological Development Laboratory National Weather Service/NOAA, Silver Spring, Maryland 1. INTRODUCTION Hurricanes storm surges and waves at the coastline Holliday (1977) developed a simple formula relating the have been the cause of damages in the coastal zone. cyclone’s pressure drop to maximum sustained wind for On the U.S. Gulf Coast, for example, Hurricane Opal the Western Pacific. A more general form was (1995) made landfall near the time of low tide and proposed by Holland (1980). The merit of these models resulted in severe flooding by storm surges and waves. is that they are analytical models for the surface wind Storm surge can penetrate miles inland from the coast. profile in a hurricane. A similar formulation was applied Waves ride above the surge levels, causing wave runup to the wave model in the present work. The framework and mean water level set-up. These wave effects are of the hurricane wave model is described below. significant near the landfall area and are affected by the process that hurricane approaches the coastline. 2.1 HURRICANE WIND AND STORM SURGES During 1950-1977, hurricane wave models based on Holland (1980) employed a standard pressure profile for significant wave height and period were developed (e.g. a tropical cyclone and obtained the popular gradient Bretschneider, 1957; Ross, 1976) for marine weather wind profile. Jelesnianski and Taylor (1976) assumed a prediction and offshore oil industry design. Cardone surface wind profile in the pressure equation. -

Marine Forecasting at TAFB [email protected]

Marine Forecasting at TAFB [email protected] 1 Waves 101 Concepts and basic equations 2 Have an overall understanding of the wave forecasting challenge • Wave growth • Wave spectra • Swell propagation • Swell decay • Deep water waves • Shallow water waves 3 Wave Concepts • Waves form by the stress induced on the ocean surface by physical wind contact with water • Begin with capillary waves with gradual growth dependent on conditions • Wave decay process begins immediately as waves exit wind generation area…a.k.a. “fetch” area 4 5 Wave Growth There are three basic components to wave growth: • Wind speed • Fetch length • Duration Wave growth is limited by either fetch length or duration 6 Fully Developed Sea • When wave growth has reached a maximum height for a given wind speed, fetch and duration of wind. • A sea for which the input of energy to the waves from the local wind is in balance with the transfer of energy among the different wave components, and with the dissipation of energy by wave breaking - AMS. 7 Fetches 8 Dynamic Fetch 9 Wave Growth Nomogram 10 Calculate Wave H and T • What can we determine for wave characteristics from the following scenario? • 40 kt wind blows for 24 hours across a 150 nm fetch area? • Using the wave nomogram – start on left vertical axis at 40 kt • Move forward in time to the right until you reach either 24 hours or 150 nm of fetch • What is limiting factor? Fetch length or time? • Nomogram yields 18.7 ft @ 9.6 sec 11 Wave Growth Nomogram 12 Wave Dimensions • C=Wave Celerity • L=Wave Length • -

2007 MTS Overview of Manned Underwater Vehicle Activity

P A P E R 2007 MTS Overview of Manned Underwater Vehicle Activity AUTHOR ABSTRACT William Kohnen There are approximately 100 active manned submersibles in operation around the world; Chair, MTS Manned Underwater in this overview we refer to all non-military manned underwater vehicles that are used for Vehicles Committee scientific, research, tourism, and commercial diving applications, as well as personal leisure SEAmagine Hydrospace Corporation craft. The Marine Technology Society committee on Manned Underwater Vehicles (MUV) maintains the only comprehensive database of active submersibles operating around the world and endeavors to continually bring together the international community of manned Introduction submersible operators, manufacturers and industry professionals. The database is maintained he year 2007 did not herald a great through contact with manufacturers, operators and owners through the Manned Submersible number of new manned submersible de- program held yearly at the Underwater Intervention conference. Tployments, although the industry has expe- The most comprehensive and detailed overview of this industry is given during the UI rienced significant momentum. Submersi- conference, and this article cannot cover all developments within the allocated space; there- bles continue to find new applications in fore our focus is on a compendium of activity provided from the most dynamic submersible tourism, science and research, commercial builders, operators and research organizations that contribute to the industry and who share and recreational work; the biggest progress their latest information through the MTS committee. This article presents a short overview coming from the least likely source, namely of submersible activity in 2007, including new submersible construction, operation and the leisure markets. -

Optimal Breathing Gas Mixture in Professional Diving with Multiple Supply

Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering 2021 WCE 2021, July 7-9, 2021, London, U.K. Optimal Breathing Gas Mixture in Professional Diving with Multiple Supply Orhan I. Basaran, Mert Unal compressors and cylinders, it was limited to surface air Abstract— Professional diving existed since antiquities when supply lines. In 1978, Fleuss introduced the first closed divers collected resources from the bottom of the seas and circuit oxygen breathing apparatus which removed carbon lakes. With technological advancements in the recent century, dioxide from the exhaled gas and did not form bubbles professional diving activities also increased significantly. underwater. In 1943, Cousteau and Gangan designed the Diving has many adverse effects on human physiology which first proper demand-regulated air supply from compressed are widely investigated in order to make dives safer. In this air cylinders worn on the back. The scuba equipment with study, we focus on optimizing the breathing gas mixture minimizing the dive costs while ensuring the safety of the the high-pressure regulator on the cylinder and a single hose divers. The methods proposed in this paper are purely to a demand valve was invented in Australia and marketed theoretical and divers should always have appropriate training by Ted Eldred in the early 1950s [1]. and certificates. Also, divers should never perform dives With the use of Siebe dress, the first cases of decompression without consulting professionals and medical doctors with expertise in related fields. sickness began to be documented. Haldane conducted several experiments on animal and human subjects in Index Terms—-professional diving; breathing gas compression chambers to investigate the causes of this optimization; dive profile optimization sickness and how it can be prevented. -

Chart Datum and Bathymetry Correction to Support Managing Coral Grouper in Lepar and Pongok Island Waters, South Bangka Regency

ILMU KELAUTAN Desember 2018 Vol 23(4):179-186 ISSN 0853-7291 Chart Datum and Bathymetry Correction to Support Managing Coral Grouper in Lepar and Pongok Island Waters, South Bangka Regency Sudirman Adibrata1,2*, Fredinan Yulianda3, Mennofatria Boer3, and I Wayan Nurjaya4 1Program of Coastal and Marine Resource Management, Bogor Agricultural University Jl. Agatis Campus IPB Darmaga Bogor 16680, Indonesia 2Program of Aquatic Resource Management, Faculty Agriculture, Fishery and Biology, Bangka Belitung Unversity Jl. Balunijuk Merawang District, Bangka, Bangka Belitung, Indonesia 3Department of Aquatic Resource Management, Fisheries and Marine Science Faculty, Bogor Agricultural University; Jl. Agatis Campus IPB Darmaga Bogor 16680, Indonesia 4Department of Marine Science and Technology, Fisheries and Marine Science, Bogor Agricultural University, Jl. Agatis Campus IPB Darmaga Bogor 16680, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract Corrected bathimetry data is highly required to improve the quality of sea floor map, for a range of purposes including coastal environmental monitoring and management. This research was aimed to know chart datum values used for correctting bathymetry data at Bar-cheeked coral trout grouper (Plectropomus maculates) fishing ground in Lepar and Pongok Island waters 02o57’00”S and 106o50’00”E and 02o53’00”S and 107o03’00”E, respectively, South Bangka Regency, Indonesia. The study was carried out from November 2016 to October 2017, tidal data used for 15 days from September 16–30, 2017 using simple random sampling technique with the total of 845 points of measurements. To calculate tyde harmonic constituents values this study employed admiralty method resulting 10 major components. Results of this research indicated that harmonic coefficient values of M2, M2, S2, N2, K1, O1, M4, MS4, K2, and P1, were 0.0345 m, 0.0608 m, 0.0276 m, 0.4262 m, 0.2060 m, 0.0119 m, 0.0082 m, 0.0164 m, and 0.1406 m, respectively. -

Coastal Tide Gauge Tsunami Warning Centers

Products and Services Available from NOAA NCEI Archive of Water Level Data Aaron Sweeney,1,2 George Mungov, 1,2 Lindsey Wright 1,2 Introduction NCEI’s Role More than just an archive. NCEI: NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) operates the World Data Service (WDS) for High resolution delayed-mode DART data are stored onboard the BPR, • Quality controls the data and Geophysics (including tsunamis). The NCEI/WDS provides the long-term archive, data management, and and, after recovery, are sent to NCEI for archive and processing. Tide models the tides to isolate the access to national and global tsunami data for research and mitigation of tsunami hazards. Archive gauge data is delivered to NCEI tsunami waves responsibilities include the global historic tsunami event and run-up database, the bottom pressure recorder directly through NOS CO-OPS and • Ensures meaningful data collected by the Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunami (DART®) Program, coastal tide gauge Tsunami Warning Centers. Upon documentation for data re-use data (analog and digital marigrams) from US-operated sites, and event-specific data from international receipt, NCEI’s role is to ensure • Creates standard metadata to gauges. These high-resolution data are used by national warning centers and researchers to increase our the data are available for use and enable search and discovery understanding and ability to forecast the magnitude, direction, and speed of tsunami events. reuse by the community. • Converts data into standard formats (netCDF) to ease data re-use The Data • Digitizes marigrams Data essential for tsunami detection and warning from • Adds data to inventory timeline the Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of to ensure no gaps in data Tsunamis (DART®) stations and the coastal tide gauges. -

Ocean Storage

277 6 Ocean storage Coordinating Lead Authors Ken Caldeira (United States), Makoto Akai (Japan) Lead Authors Peter Brewer (United States), Baixin Chen (China), Peter Haugan (Norway), Toru Iwama (Japan), Paul Johnston (United Kingdom), Haroon Kheshgi (United States), Qingquan Li (China), Takashi Ohsumi (Japan), Hans Pörtner (Germany), Chris Sabine (United States), Yoshihisa Shirayama (Japan), Jolyon Thomson (United Kingdom) Contributing Authors Jim Barry (United States), Lara Hansen (United States) Review Editors Brad De Young (Canada), Fortunat Joos (Switzerland) 278 IPCC Special Report on Carbon dioxide Capture and Storage Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 279 6.7 Environmental impacts, risks, and risk management 298 6.1 Introduction and background 279 6.7.1 Introduction to biological impacts and risk 298 6.1.1 Intentional storage of CO2 in the ocean 279 6.7.2 Physiological effects of CO2 301 6.1.2 Relevant background in physical and chemical 6.7.3 From physiological mechanisms to ecosystems 305 oceanography 281 6.7.4 Biological consequences for water column release scenarios 306 6.2 Approaches to release CO2 into the ocean 282 6.7.5 Biological consequences associated with CO2 6.2.1 Approaches to releasing CO2 that has been captured, lakes 307 compressed, and transported into the ocean 282 6.7.6 Contaminants in CO2 streams 307 6.2.2 CO2 storage by dissolution of carbonate minerals 290 6.7.7 Risk management 307 6.2.3 Other ocean storage approaches 291 6.7.8 Social aspects; public and stakeholder perception 307 6.3 Capacity and fractions retained -

Estimation of Significant Wave Height Using Satellite Data

Research Journal of Applied Sciences, Engineering and Technology 4(24): 5332-5338, 2012 ISSN: 2040-7467 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2012 Submitted: March 18, 2012 Accepted: April 23, 2012 Published: December 15, 2012 Estimation of Significant Wave Height Using Satellite Data R.D. Sathiya and V. Vaithiyanathan School of Computing, SASTRA University, Thirumalaisamudram, India Abstract: Among the different ocean physical parameters applied in the hydrographic studies, sufficient work has not been noticed in the existing research. So it is planned to evaluate the wave height from the satellite sensors (OceanSAT 1, 2 data) without the influence of tide. The model was developed with the comparison of the actual data of maximum height of water level which we have collected for 24 h in beach. The same correlated with the derived data from the earlier satellite imagery. To get the result of the significant wave height, beach profile was alone taking into account the height of the ocean swell, the wave height was deduced from the tide chart. For defining the relationship between the wave height and the tides a large amount of good quality of data for a significant period is required. Radar scatterometers are also able to provide sea surface wind speed and the direction of accuracy. Aim of this study is to give the relationship between the height, tides and speed of the wind, such relationship can be useful in preparing a wave table, which will be of immense value for mariners. Therefore, the relationship between significant wave height and the radar backscattering cross section has been evaluated with back propagation neural network algorithm.