The Transition and Reinvention of British Army Infantrymen May 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Are the Perceptions of Phase 1 Military Instructors Regarding Their Role?

What are the perceptions of Phase 1 Military Instructors regarding their role? Jamie Russell Webb-Fryer Master of Arts by Research University of York Education December 2015 Abstract The aim of this research was to investigate the perceptions of phase 1 military instructors regarding their role and perceived effectiveness in the delivery of teaching. It further examined, whether phase 1 instructors believe their current delivery methods and intuitional parameters allow them to provide a dynamic and less didactic learning experience. It, in addition, investigated their views and perceptions in to the military pre- employment instructional training and Continuous Professional Development (CPD) that they have been offered. The thesis followed a five chapter layout, firstly introducing and giving a detailed description into the manner in which military training is organised, then specifically analysing the organisation of military phase 1 training. The introduction further focused on the military instructor and how they integrate within the current military Army Instructor Functional Competency Framework. The literature review undertook a broad context of reading relevant to the subject. It explored other author’s views, opinions and facts in relation to the military instructor’s capability. The research methodology used in this thesis analysed the relationship and conceptual structure of the questionnaire and interview questions against specific quantitative and qualitative questions combining the overall research questions. Using different methodology of data collection for the research, the researcher hoped the data provided may point to certain themes within the findings and conclusions. 69 participants completed the paper questionnaire and 8 participants were interviewed. The findings of this research critically analysed the spectrum of perceptions from the military phase 1 instructor including both qualitative and quantitative data from the interviews and the questionnaires collection methods. -

1 Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 18 March 2010 Information as to what recent wars Sierra Leone has been involved in and when they ended. In a section titled “History” the United Kingdom Foreign & Commonwealth Office country profile for Sierra Leone states: “The SLPP ruled until 1967 when the electoral victory of the opposition APC was cut short by the country's first military coup. But the military eventually handed over to the APC and its leader Siaka Stevens in 1968. He turned the country into a one -party state in 1978. He finally retired in 1985, handing over to his deputy, General Momoh. Under popular pressure, one party rule was ended in 1991, and a new constitution providing for a return to multi-party politics was approved in August of that year. Elections were scheduled for 1992. But, by this stage, Sierra Leone's institutions had collapsed, mismanagement and corruption had ruined the economy and rising youth unemployment was a serious problem. Taking advantage of the collapse, a rebel movement, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) emerged, with backing from a warlord, Charles Taylor, in neighbouring Liberia, and in 1991 led a rebellion against the APC government. The government was unable to cope with the insurrection, and was overthrown in a junior Officers coup in April 1992. Its leader, Capt Strasser, was however unable to defeat the RUF. Indeed, the military were more often than not complicit with the rebels in violence and looting.” (United Kingdom Foreign & Commonwealth Office (25 February 2009) Country Profiles: Sub-Saharan Africa – Sierra Leone) This profile summarises the events of the period 1996 to 2002 as follows: “Strasser was deposed in January 1996 by his fellow junta leaders. -

Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 1 (A) – January 2003 I was captured together with my husband, my three young children and other civilians as we were fleeing from the RUF when they entered Jaiweii. Two rebels asked to have sex with me but when I refused, they beat me with the butt of their guns. My legs were bruised and I lost my three front teeth. Then the two rebels raped me in front of my children and other civilians. Many other women were raped in public places. I also heard of a woman from Kalu village near Jaiweii being raped only one week after having given birth. The RUF stayed in Jaiweii village for four months and I was raped by three other wicked rebels throughout this A woman receives psychological and medical treatment in a clinic to assist rape period. victims in Freetown. In January 1999, she was gang-raped by seven revels in her village in northern Sierra Leone. After raping her, the rebels tied her down and placed burning charcoal on her body. (c) 1999 Corinne Dufka/Human Rights -Testimony to Human Rights Watch Watch “WE’LL KILL YOU IF YOU CRY” SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE SIERRA LEONE CONFLICT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 2003 Vol. -

18News from the Royal School of Military

RSME MATTERSNEWS FROM THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF MILITARY ENGINEERING GROUP 18 NOVEMBER 2018 Contents 4 5 11 DEMS BOMB DISPOSAL TRAINING UPDATE Defence Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD), It’s the ten-year anniversary of the signing of the Munitions and Search Training Regiment (DEMS RSME Public Private Partnership (PPP) Contract Trg Regt) operates across two sites. The first is and that decade has seen an impressive amount the more established... Read more on page 5 of change. A casual.. Read more on page 11 WELCOME Welcome to issue 18 of RSME Matters. Much has 15 changed across the RSME Group since issue 17 but the overall challenge, of delivering appropriately trained soldiers FEATURE: INNOVATION and military working animals... The Royal School of Military Engineering (RSME) Private Public Partnership (PPP) between the Secretary of State for Defence and... Read more on page 4 Read more on page 15 We’re always looking for new parts of the RSME to explore and share Front cover: Bomb disposal training in action at DEMS Trg Regt – see story on page 9. within RSME Matters. If you’d like us to tell your story then just let us know. Back cover: Royal Engineers approach the Rochester Bridge over the river Medway during a recent night exercise. Nicki Lockhart, Editor, [email protected] Photography: All images except where stated by Ian Clowes | goldy.uk Ian Clowes, Writer and Photographer, 07930 982 661 | [email protected] Design and production: Plain Design | plaindesign.co.uk Printed on FSC® (Forest Stewardship Council) certified paper, which supports the growth of responsible forest management worldwide. -

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities

Battle Management Language: History, Employment and NATO Technical Activities Mr. Kevin Galvin Quintec Mountbatten House, Basing View, Basingstoke Hampshire, RG21 4HJ UNITED KINGDOM [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is one of a coordinated set prepared for a NATO Modelling and Simulation Group Lecture Series in Command and Control – Simulation Interoperability (C2SIM). This paper provides an introduction to the concept and historical use and employment of Battle Management Language as they have developed, and the technical activities that were started to achieve interoperability between digitised command and control and simulation systems. 1.0 INTRODUCTION This paper provides a background to the historical employment and implementation of Battle Management Languages (BML) and the challenges that face the military forces today as they deploy digitised C2 systems and have increasingly used simulation tools to both stimulate the training of commanders and their staffs at all echelons of command. The specific areas covered within this section include the following: • The current problem space. • Historical background to the development and employment of Battle Management Languages (BML) as technology evolved to communicate within military organisations. • The challenges that NATO and nations face in C2SIM interoperation. • Strategy and Policy Statements on interoperability between C2 and simulation systems. • NATO technical activities that have been instigated to examine C2Sim interoperation. 2.0 CURRENT PROBLEM SPACE “Linking sensors, decision makers and weapon systems so that information can be translated into synchronised and overwhelming military effect at optimum tempo” (Lt Gen Sir Robert Fulton, Deputy Chief of Defence Staff, 29th May 2002) Although General Fulton made that statement in 2002 at a time when the concept of network enabled operations was being formulated by the UK and within other nations, the requirement remains extant. -

Royal Bermuda Regiment (Junior Leaders) Act 2015

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA ROYAL BERMUDA REGIMENT (JUNIOR LEADERS) ACT 2015 2015 : 54 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Citation 2 Interpretation 3 Junior Leaders 4 Commandant and officers of the Junior Leaders 5 Constitution of the Junior Leaders 6 Management and control of the Junior Leaders 7 Military discipline: officers 8 Rules 9 Funds and gifts for the Junior Leaders 10 Repeal of Bermuda Cadet Corps Act 1944 11 Consequential amendments 12 Commencement and transitional provision WHEREAS it is expedient to repeal and re-enact the Bermuda Cadet Corps Act 1944 with amendments to reflect the current organisation known as the Royal Bermuda Regiment Junior Leaders; Be it enacted by The Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and the House of Assembly of Bermuda, and by the authority of the same, as follows: Citation 1 This Act may be cited as the Royal Bermuda Regiment (Junior Leaders) Act 2015. Interpretation 2 In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires— 1 ROYAL BERMUDA REGIMENT (JUNIOR LEADERS) ACT 2015 “Commanding Officer” has the meaning given in section 1 of the Defence Act 1965; “repealed Act” means the Bermuda Cadet Corps Act 1944 (repealed by section 10); “students” means persons between the age of 13 and 18 years (inclusive). Junior Leaders 3 (1) The organisation known as “The Bermuda Cadet Corps”, which was continued in being under the repealed Act, and the organisation known as the Junior Leaders shall be amalgamated and continued as a company of the Bermuda Regiment under the name “Junior Leaders”. -

Army Foundation College INSPECTION REPORT

INSPECTION REPORT Army Foundation College 18 March 2002 ARMY FOUNDATION COLLEGE Grading Inspectors use a seven-point scale to summarise their judgements about the quality of learning sessions. The descriptors for the seven grades are: • grade 1 - excellent • grade 2 - very good • grade 3 - good • grade 4 - satisfactory • grade 5 - unsatisfactory • grade 6 - poor • grade 7 - very poor. Inspectors use a five-point scale to summarise their judgements about the quality of provision in occupational/curriculum areas and in New Deal options. The same scale is used to describe the quality of leadership and management, which includes quality assurance and equality of opportunity. The descriptors for the five grades are: • grade 1 - outstanding • grade 2 - good • grade 3 - satisfactory • grade 4 - unsatisfactory • grade 5 - very weak. The two grading scales relate to each other as follows: SEVEN-POINT SCALE FIVE-POINT SCALE grade 1 grade 1 grade 2 grade 3 grade 2 grade 4 grade 3 grade 5 grade 4 grade 6 grade 5 grade 7 ARMY FOUNDATION COLLEGE Adult Learning Inspectorate The Adult Learning Inspectorate (ALI) was established under the provisions of the Learning and Skills Act 2000 to bring the inspection of all aspects of adult learning and work-based training within the remit of a single inspectorate. The ALI is responsible for inspecting a wide range of government-funded learning, including: • work-based training for all people over 16 • provision in further education colleges for people aged 19 and over • the University for Industry’s learndirect provision • adult and community learning • training given by the Employment Service under the New Deals. -

Terminology & Rank Structure

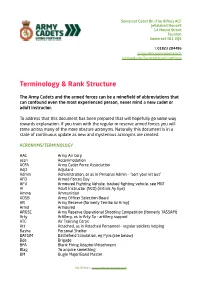

Somerset Cadet Bn (The Rifles) ACF Jellalabad HouseS 14 Mount Street Taunton Somerset TA1 3QE t: 01823 284486 armycadets.com/somersetacf/ facebook.com/SomersetArmyCadetForce Terminology & Rank Structure The Army Cadets and the armed forces can be a minefield of abbreviations that can confound even the most experienced person, never mind a new cadet or adult instructor. To address that this document has been prepared that will hopefully go some way towards explanation. If you train with the regular or reserve armed forces you will come across many of the more obscure acronyms. Naturally this document is in a state of continuous update as new and mysterious acronyms are created. ACRONYMS/TERMINOLOGY AAC Army Air Corp accn Accommodation ACFA Army Cadet Force Association Adjt Adjutant Admin Administration, or as in Personal Admin - “sort your kit out” AFD Armed Forces Day AFV Armoured Fighting Vehicle, tracked fighting vehicle, see MBT AI Adult Instructor (NCO) (initials Ay Eye) Ammo Ammunition AOSB Army Officer Selection Board AR Army Reserve (formerly Territorial Army) Armd Armoured AROSC Army Reserve Operational Shooting Competition (formerly TASSAM) Arty Artillery, as in Arty Sp - artillery support ATC Air Training Corps Att Attached, as in Attached Personnel - regular soldiers helping Basha Personal Shelter BATSIM Battlefield Simulation, eg Pyro (see below) Bde Brigade BFA Blank Firing Adaptor/Attachment Blag To acquire something BM Bugle Major/Band Master 20170304U - armycadets.com/somersetacf Bn Battalion Bootneck A Royal Marines Commando -

Finding Aid - Huw T

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Huw T. Edwards Papers, (GB 0210 HUWRDS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/huw-t-edwards-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/huw-t-edwards-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Huw T. Edwards Papers, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access -

Armed Forces Covenant Across Gwent NEWS Summer 2020

Armed Forces Covenant across Gwent NEWS Summer 2020 Armed Forces Covenant across Gwent The Covenant is a promise from the nation ensuring that those who serve and have served in the Armed Forces and their families are treated fairly. Victory in Europe Day VE Day – or ‘Victory in Europe Day’ marks the day towards the end of World War Two (WW2) when ghting against Nazi Germany in Europe came to an end. Tuesday 8 May, 1945, was an emotional day that millions of people had been waiting for. Many people were extremely happy that the ghting had stopped and there were big celebrations and street parties. In his VE Day announcement, Winston Churchill said: “We may allow ourselves a brief period of rejoicing, but let us not forget for a moment the toil and e orts that lie ahead.” Even after 8 May, many soldiers, sailors and pilots were sent to the east to ght against the Japanese, who had not yet surrendered. VE Day celebrations were curtailed as a result of the coronavirus lockdown. Armed Forces Covenant Training Package The WLGA, with funding from the Covenant Fund, commissioned Cardi and Vale College to produce an Armed Forces Covenant training package. The package consists of a face-to-face training resource together with an e-learning resource. Both resources are aimed at local authority elected members and sta and seek to raise awareness and understanding of the Covenant. If you would like bespoke training for your department please contact Lisa Rawlings - Regional Armed Forces Covenant Offi cer [email protected] 01443 864447 www.covenantwales.wales/e-learning/ Armed Forces Covenant across Gwent p. -

Wire April 2013

THE wire April 2013 www.royalsignals.mod.uk The Magazine of The Royal Corps of Signals We are proud to inform you of the new Armed Forces Hindu Network The centre point for all Hindu activities across MoD Its purpose is to: • Inform members of development in the wider Armed Forces. • Provide an inclusive platform for discussions and meetings for serving Hindus. • Keep the Hindu community in the Armed Forces, including civilian sta, informed on: - Cultural & Spiritual matters and events. - Seminars with external speakers. (Membership is free) For further information, please contact: Captain P Patel RAMC (Chairman) Email: [email protected] Mobile: 07914 06665 / 01252 348308 Flight Lieutenant V Mungroo RAF (Dep Chair) Deputy Chairman Email: [email protected] WO1 AK Chauhan MBE (Media & Comms) Email: [email protected] Mobile: 07919 210525 / 01252 348 308 FEBRUARY 2013 Vol. 67 No: 2 The Magazine of the Royal Corps of Signals Established in 1920 Find us on The Wire Published bi-monthly Annual subscription £12.00 plus postage Editor: Mr Keith Pritchard Editor Deputy Editor: Ms J Burke Mr Keith Pritchard Tel: 01258 482817 All correspondence and material for publication in The Wire should be addressed to: The Wire, RHQ Royal Signals, Blandford Camp, Blandford Forum, Dorset, DT11 8RH Email: [email protected] Contributors Deadline for The Wire : 15th February for publication in the April. 15th April for publication in the June. 15th June for publication in the August. 15th August for publication in the October. 15th October for publication in the December. Accounts / Subscriptions 10th December for publication in the February. -

City of Cardiff Council Letting Boards Evidence Report

City of Cardiff Council Letting Boards Evidence Report Submission to the Welsh Planning Minister for a Direction under Regulation 7 of the Town and County Planning (Control of Advertisements) Regulations 1992 October 2014 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Legislation & policy 3. Area of Proposed Control 4. Policy initiatives to address the impact of high student populations and HMOs 5. Adverse impact of letting boards 6. Action taken to minimise the effects of letting boards 7. Survey and consultation to support this submission 8. Character appraisal and visual amenity assessment 9. Future enforcement strategy 10. Impact of the proposed controls on existing businesses 11. Conclusions Appendices 1. Proposed Direction Area 2. Cathays and Plasnewydd Ward Profiles ‐ 2011 Census 3. (to follow when approved) Cardiff Student Community Action Plan 2014 – 2017 4. City of Cardiff Council Cabinet Reports – Plasnewydd HMO Licensing (July 2014) 5. City of Cardiff Council Executive (March 2012) and Cabinet (March 2014) Reports 6. Public Consultation Report 7. Landlord and Letting Agent Consultation Report 8. Draft Policy Guidance ‐ Consultation Version ‐ July 2014 9. 2010 Letting Board Survey ‐ Cathays 10. 2014 Letting Board Survey – Cathays and Plasnewydd 11. Petition received by the Council – May 2014 12. Policy Guidance ‐ Final Draft Version – Oct 2014 13. OFT Report ‐ Home Buying and Selling Market Study – Feb 2010 14. UK Estate Agents and Solicitors/Conveyancers Survey 2011 ‐ Homesalone Report – April 2011 1.0 Introduction 1.1 The City of Cardiff Council requests that the Welsh Planning Minister grant a Direction under Regulation 7 of the Town and County Planning (Control of Advertisements) Regulations 1992 that deemed consent for the display of letting boards relating to residential property, which are advertisements within Schedule 3, Part 1, Class 3A of the regulations, should not apply to parts of the Cathays and Plasnewydd wards of Cardiff (the proposed ‘Direction Area’) as identified on the attached plan (Appendix 1).