Case Closed Rape and Human Rights in the Nordic Countries Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

Star Channels, May 3-9, 2020

MAY 3 - 9, 2020 staradvertiser.com MONEY PROBLEMS Showtime’s most provocative corporate drama, Billions, returns for its fi fth season and fans of the show can’t wait to see more of their favorite fi ctional billionaires as they scheme and slither their way to the top of the Wall Street food chain. Paul Giamatti and Damian Lewis star, while Julianna Margulies and Corey Stoll join the cast. Airing Sunday, May 3, on Showtime. A SPECIAL COVID-19 PRESENTATION Join host, Lyla Berg as she speaks with community experts about COVID-19. Tune in Wednesday, May 6 and May 20 at 6:30pm on Channel 53 WEDNESDAYW at 6:30pm - - olelo.org Also available on Olelonet and Olelo YouTube. Channel 53 ¶ ¶ 590126_IslandFocus_Ad_COVID19_2in_R.indd 1 4/30/20 9:29 AM ON THE COVER | BILLIONS A few billion more Wall Street gets a new Prince by the coronavirus pandemic. The first seven disappearance in Season 1 to the two men episodes will air starting this week, and the going head to head in court in Season 3, it ap- in Season 5 of ‘Billions’ show will take a break mid-June at a natural pears the billionaires will squabble over just point in the story arc. At this stage, there is about anything from money and business to By Dana Simpson no way to know when the second part of the women and politics. TV Media season will air, but the much-anticipated re- Just when it seemed they would band maining episodes will be filmed and released together to form an alliance — especially asten your seatbelts for another year of as soon as the production process is safe to with Axe’s focus now more clearly aimed dollars and deceit. -

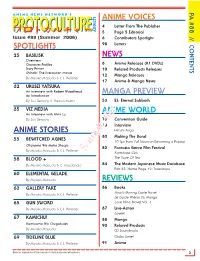

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

Sides Do Not Need to Be Memorized

Page 12 of 103 September 24, 2019 RAPP: You sure? CARSON: Yup! RAPP: Okay- CARSON: Honestly, you seem a little young. RAPP: Hey, you too, but I’m VERY good with missing persons, so good, in fact, that Mrs. Kalles of “Kalles Yoghurt” - you ever tried that yoghurt? CARSON: No. RAPP: Little sticks, like a Freezie but it’s yoghurt?* CARSON: No. RAPP: *UNREAL - anyway, I’m so good, she hired me to look into the disappearance of her son, Henry, who your department out here is having a hard time locating…hope that's not awkward. CARSON: (beat) Mr. Rapp- RAPP: Detective. CARSON: We…I have…reason to believe he is in Europe… RAPP: Right, plane ticket to Prague the night of the 15th. Top notch police work/ you think… CARSON: Ten thousand dollars cash withdrawn from / his bank account RAPP: Oh my, ten THOUSAND dollars, looks like he’s gonna stay/ awhile. CARSON: Okay, then his mother told you that he’s done this before, yes? Twice, each time without notice - takes out cash so his mother can't track his cards. RAPP: Sure, but she hasn’t heard ANYTHING from him? CARSON: We’ve called the embassy in Prague. Nothing. RAPP: But we don’t even know if he got on the plane. Because the day he left the airline’s system got scrambled, right – which is crazy, and there’s no passenger manifest for that flight the night of the 15th. (CARSON: Yes/but) The last time anyone saw him was that morning, here in Whittock. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

Sailor Mars Meet Maroku

sailor mars meet maroku By GIRNESS Submitted: August 11, 2005 Updated: August 11, 2005 sailor mars and maroku meet during a battle then fall in love they start to go futher and futher into their relationship boy will sango be mad when she comes back =:) hope you like it Provided by Fanart Central. http://www.fanart-central.net/stories/user/GIRNESS/18890/sailor-mars-meet-maroku Chapter 1 - sango leaves 2 Chapter 2 - sango leaves 15 1 - sango leaves Fanart Central A.whitelink { COLOR: #0000ff}A.whitelink:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.whitelink:visited { COLOR: #0000ff}A.BoxTitleLink { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:hover { COLOR: #465584; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.BoxTitleLink:visited { COLOR: #000; TEXT-DECORATION: underline}A.normal { COLOR: blue}A.normal:hover { BACKGROUND-COLOR: transparent}A.normal:visited { COLOR: #000020}A { COLOR: #0000dd}A:hover { COLOR: #cc0000}A:visited { COLOR: #000020}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper { COLOR: #ff0000}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:hover { COLOR: #ffaaaa}A.onlineMemberLinkHelper:visited { COLOR: #cc0000}.BoxTitleColor { COLOR: #000000} picture name Description Keywords All Anime/Manga (0)Books (258)Cartoons (428)Comics (555)Fantasy (474)Furries (0)Games (64)Misc (176)Movies (435)Original (0)Paintings (197)Real People (752)Tutorials (0)TV (169) Add Story Title: Description: Keywords: Category: Anime/Manga +.hack // Legend of Twilight's Bracelet +Aura +Balmung +Crossovers +Hotaru +Komiyan III +Mireille +Original .hack Characters +Reina +Reki +Shugo +.hack // Sign +Mimiru -

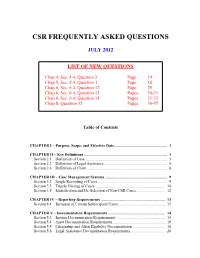

Csr Frequently Asked Questions

CSR FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS JULY 2012 LIST OF NEW QUESTIONS Chap 4, Sec. 4.4, Question 2 Page 14 Chap 5, Sec. 5.4, Question 1 Page 16 Chap 6, Sec. 6.4, Question 12 Page 29 Chap 6, Sec. 6.4, Question 13 Pages 30-31 Chap 6, Sec. 6.4, Question 14 Pages 31-32 Chap 8, Question 32 Pages 56-57 Table of Contents CHAPTER I – Purpose, Scope, and Effective Date ...................................................... 3 CHAPTER II – Key Definitions ..................................................................................... 3 Section 2.1 – Definition of Case .................................................................................... 3 Section 2.2 – Definition of Legal Assistance................................................................. 4 Section 2.4 – Definition of Client .................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER III – Case Management Systems ................................................................ 9 Section 3.2 – Single Recording of Cases ....................................................................... 9 Section 3.3 – Timely Closing of Cases ........................................................................ 10 Section 3.5 – Identification and De-Selection of Non-CSR Cases .............................. 12 CHAPTER IV – Reporting Requirements .................................................................. 13 Section 4.4 – Inclusion of Certain Subrecipient Cases ................................................ 13 CHAPTER V – Documentation Requirements -

2013 1St Quarter

Juan F. v. Malloy Exit Plan Quarterly Report June 2013 Juan F. v. Malloy Exit Plan Quarterly Report January 1, 2013 - March 31, 2013 Civil Action No. 2:89 CV 859 (SRU) Submitted by: DCF Court Monitor's Office 300 Church St, 4th Floor Wallingford, CT 06492 Tel: 203-741-0458 Fax: 203-741-0462 E-Mail: [email protected] Juan F. v. Malloy Exit Plan Quarterly Report June 2013 Table of Contents Juan F. v Malloy Exit Plan Quarterly Report January 1, 2013 - March 31, 2013 Section Page Highlights 3 Juan F. Exit Plan Outcome Measure Overview Chart 8 (January 1, 2013 - March 31, 2013) 9 Juan F. Pre-Certification Review-Status Update First Quarter 2013 44 Monitor's Office Case Review for Outcome Measure 3 and Outcome Measure 15 66 Juan F. Action Plan Monitoring Report Appendix 1 - Commissioner's Highlights from: The Department of 80 Children and Families Exit Plan Outcome Measures Summary Report: First Quarter Report (January 1, 2013 - March 31, 2013) 2 Juan F. v. Malloy Exit Plan Quarterly Report June 2013 Juan F. v Malloy Exit Plan Quarterly Report January 1, 2013 - March 31, 2013 Highlights • The Court Monitor's quarterly review of the Department's efforts to meet the Exit Plan Outcome Measures during the period of January 1, 2013 through March 31, 2013 indicates the Department achieved 13 of the 22 Outcome Measures. The nine measures not met include: Outcome Measure 3 (Case Planning), Outcome Measure 7 (Reunification), Outcome Measure 8 (Adoption), Outcome Measure 10 (Sibling Placements), Outcome Measure 11 (Re-Entry into DCF Custody), Outcome Measure 15 (Children's Needs Met), Outcome Measure 17 (Worker-Child Visitation In-Home)1, Outcome Measure 18 (Caseload Standards), and Outcome Measure 21 (Discharge to Adult Services). -

Protoculture Addicts Is ©1987-2006 by Protoculture • the REVIEWS Copyrights and Trademarks Mentioned Herein Are the Property of LIVE-ACTION

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ P r o t o c u l t u r e A d d i c t s # 8 7 December 2005 / January 2006. Published by Protoculture, P.O. Box 1433, Station B, Montreal, Qc, Canada, H3B 3L2. ANIME VOICES Letter From The Publisher ......................................................................................................... 4 E d i t o r i a l S t a f f Page Five Editorial ................................................................................................................... 5 [CM] – Publisher Christopher Macdonald Contributor Spotlight & Staff Lowlight ......................................................................................... 6 [CJP] – Editor-in-chief Claude J. Pelletier Letters ................................................................................................................................... 74 [email protected] Miyako Matsuda [MM] – Contributing Editor / Translator Julia Struthers-Jobin – Editor NEWS Bamboo Dong [BD] – Associate-Editor ANIME RELEASES (R1 DVDs) ...................................................................................................... 7 Jonathan Mays [JM] – Associate-Editor ANIME-RELATED PRODUCTS RELEASES (UMDs, CDs, Live-Action DVDs, Artbooks, Novels) .................. 9 C o n t r i b u t o r s MANGA RELEASES .................................................................................................................. 10 Zac Bertschy [ZB], Sean Broestl [SB], Robert Chase [RC], ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North -

Supsensions and Debarments

APPENDIX E SUSPENSIONS AND DEBARMENTS Th is appendix presents a comprehensive list of suspensions and debarments related to Iraq reconstruction contracts or Army support contracts in Iraq and Kuwait. ◆ Table E.1 Suspensions and Debarments (Army) Suspension and Reason for Name Position Debarment Action Taken Action Case Status Awarded contract to KBR subcontractor under Suspended, 9/17/2005; LOGCAP III contract in exchange for 20% kickback Employee, proposed for debarment, Bribery of Government Powell, Glenn Allen of contract price. Employer unaware of actions. On LOGCAP Contractor 12/13/2005; debarred, Offi cial 8/19/2005, pled guilty to a two-count criminal informa- 2/16/2006 tion charging him with fraud. Case closed. Suspended, 7/25/2005; LOGCAP proposed for debarment, Allegations of Failure Failure to perform a contract for the delivery of ice to DXB International Subcontractor 7/25/2005; debarred, To Perform a Contract Army troops in Iraq. Case closed. 9/29/2005 Suspended, 7/25/2005; SDO determined that debarment was not appropriate Employee, DXB Allegations of Failure Name Withheld proposed for debarment, based on lack of substantiation of allegations. Case International To Perform a Contract 7/25/2005 closed. Suspended, 7/25/2005; Employee, DXB proposed for debarment, Allegations of Failure Failure to perform a contract for the delivery of ice to Ludwig, Steven International 7/25/2005; debarred, To Perform a Contract Army troops in Iraq. Case closed. 9/29/2005 Provided payments to Army fi nance offi ce personnel Proposed for debarment, Jasmine at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait, for expedition of payments Contractor, Area 2/27/2006; debarred, International Bribery of Government due on Army contracts. -

Copy of Anime Licensing Information

Title Owner Rating Length ANN .hack//G.U. Trilogy Bandai 13UP Movie 7.58655 .hack//Legend of the Twilight Bandai 13UP 12 ep. 6.43177 .hack//ROOTS Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.60439 .hack//SIGN Bandai 13UP 26 ep. 6.9994 0091 Funimation TVMA 10 Tokyo Warriors MediaBlasters 13UP 6 ep. 5.03647 2009 Lost Memories ADV R 2009 Lost Memories/Yesterday ADV R 3 x 3 Eyes Geneon 16UP 801 TTS Airbats ADV 15UP A Tree of Palme ADV TV14 Movie 6.72217 Abarashi Family ADV MA AD Police (TV) ADV 15UP AD Police Files Animeigo 17UP Adventures of the MiniGoddess Geneon 13UP 48 ep/7min each 6.48196 Afro Samurai Funimation TVMA Afro Samurai: Resurrection Funimation TVMA Agent Aika Central Park Media 16UP Ah! My Buddha MediaBlasters 13UP 13 ep. 6.28279 Ah! My Goddess Geneon 13UP 5 ep. 7.52072 Ah! My Goddess MediaBlasters 13UP 26 ep. 7.58773 Ah! My Goddess 2: Flights of Fancy Funimation TVPG 24 ep. 7.76708 Ai Yori Aoshi Geneon 13UP 24 ep. 7.25091 Ai Yori Aoshi ~Enishi~ Geneon 13UP 13 ep. 7.14424 Aika R16 Virgin Mission Bandai 16UP Air Funimation 14UP Movie 7.4069 Air Funimation TV14 13 ep. 7.99849 Air Gear Funimation TVMA Akira Geneon R Alien Nine Central Park Media 13UP 4 ep. 6.85277 All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Dash! ADV 15UP All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku TV ADV 12UP 14 ep. 6.23837 Amon Saga Manga Video NA Angel Links Bandai 13UP 13 ep. 5.91024 Angel Sanctuary Central Park Media 16UP Angel Tales Bandai 13UP 14 ep. -

TITLES = (Language: EN Version: 20101018083045

TITLES = http://wiitdb.com (language: EN version: 20101018083045) 010E01 = Wii Backup Disc DCHJAF = We Cheer: Ohasta Produce ! Gentei Collabo Game Disc DHHJ8J = Hirano Aya Premium Movie Disc from Suzumiya Haruhi no Gekidou DHKE18 = Help Wanted: 50 Wacky Jobs (DEMO) DMHE08 = Monster Hunter Tri Demo DMHJ08 = Monster Hunter Tri (Demo) DQAJK2 = Aquarius Baseball DSFE7U = Muramasa: The Demon Blade (Demo) DZDE01 = The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (E3 2006 Demo) R23E52 = Barbie and the Three Musketeers R23P52 = Barbie and the Three Musketeers R24J01 = ChibiRobo! R25EWR = LEGO Harry Potter: Years 14 R25PWR = LEGO Harry Potter: Years 14 R26E5G = Data East Arcade Classics R27E54 = Dora Saves the Crystal Kingdom R27X54 = Dora Saves The Crystal Kingdom R29E52 = NPPL Championship Paintball 2009 R29P52 = Millennium Series Championship Paintball 2009 R2AE7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2AP7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2AX7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2DEEB = Dokapon Kingdom R2DJEP = Dokapon Kingdom For Wii R2DPAP = Dokapon Kingdom R2DPJW = Dokapon Kingdom R2EJ99 = Fish Eyes Wii R2FE5G = Freddi Fish: Kelp Seed Mystery R2FP70 = Freddi Fish: Kelp Seed Mystery R2GEXJ = Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon R2GJAF = Fragile: Sayonara Tsuki no Haikyo R2GP99 = Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon R2HE41 = Petz Horse Club R2IE69 = Madden NFL 10 R2IP69 = Madden NFL 10 R2JJAF = Taiko no Tatsujin Wii R2KE54 = Don King Boxing R2KP54 = Don King Boxing R2LJMS = Hula Wii: Hura de Hajimeru Bi to Kenkou!! R2ME20 = M&M's Adventure R2NE69 = NASCAR Kart Racing