Hear the Music, Play the Game Music and Game Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Gaming Music: Composition

KSKS45 Computer gaming music: composition James Manwaring by James Manwaring is Director of Music for Windsor Learning Partnership, and has been teaching music for 15 years. He is a member of INTRODUCTION the MMA and ISM, and he writes his One of the key emerging genres of music over the last 35 years has been computer game music. Since the own music blog. first playable version of Tetris in 1984, music in this genre has grown. We now see key orchestral and cinema composers turning their hands to computer game soundtracks. If we’re going to prepare our students for future work in the music industry, it’s crucial for them to embrace all styles and genres. Following an earlier resource on gaming music (AQA AoS2: Computer gaming music, Music Teacher, November 2018), here I’m going to consider ways of teaching computer game music using composition. This will include some compositional ideas that can easily be adapted for other genres. STARTING POINT Composition is a key component for all the GCSE exam boards, and while each exam board has different criteria, they all share similar, overarching compositional goals. The ideas in this resource can either lead to something suitable for a GCSE entry, or help with the overall teaching of composition. The aim is to use computer games as the key focus for the composing process. Students will probably spend a great deal of time playing computer games. Not only will they have an excellent grasp of music from this genre, but they will also be keen to have a go at composing it for themselves. -

The Effects of Background Music on Video Game Play Performance, Behavior and Experience in Extraverts and Introverts

THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Laura Levy In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Psychology in the School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology December 2015 Copyright © Laura Levy 2015 THE EFFECTS OF BACKGROUND MUSIC ON VIDEO GAME PLAY PERFORMANCE, BEHAVIOR, AND EXPERIENCE IN EXTRAVERTS AND INTROVERTS Approved by: Dr. Richard Catrambone Advisor School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Bruce Walker School of Psychology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Maribeth Coleman Institute for People and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: 17 July 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the researchers and students that made Food for Thought possible as the wonderful research tool it is today. Special thanks to Rob Solomon, whose efforts to make the game function specifically for this project made it a success. Additionally, many thanks to Rob Skipworth, whose audio engineering expertise made the soundtrack of this study sound beautifully. I express appreciation to the Interactive Media Technology Center (IMTC) for the support of this research, and to my committee for their guidance in making it possible. Finally, I wish to express gratitude to my family for their constant support and quiet bemusement for my seemingly never-ending tenure in graduate school. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii LIST OF -

The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 122–135 Research Article Adam de Paor-Evans* The Futurism of Hip Hop: Space, Electro and Science Fiction in Rap https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0012 Received January 27, 2018; accepted June 2, 2018 Abstract: In the early 1980s, an important facet of hip hop culture developed a style of music known as electro-rap, much of which carries narratives linked to science fiction, fantasy and references to arcade games and comic books. The aim of this article is to build a critical inquiry into the cultural and socio- political presence of these ideas as drivers for the productions of electro-rap, and subsequently through artists from Newcleus to Strange U seeks to interrogate the value of science fiction from the 1980s to the 2000s, evaluating the validity of science fiction’s place in the future of hip hop. Theoretically underpinned by the emerging theories associated with Afrofuturism and Paul Virilio’s dromosphere and picnolepsy concepts, the article reconsiders time and spatial context as a palimpsest whereby the saturation of digitalisation becomes both accelerator and obstacle and proposes a thirdspace-dromology. In conclusion, the article repositions contemporary hip hop and unearths the realities of science fiction and closes by offering specific directions for both the future within and the future of hip hop culture and its potential impact on future society. Keywords: dromosphere, dromology, Afrofuturism, electro-rap, thirdspace, fantasy, Newcleus, Strange U Introduction During the mid-1970s, the language of New York City’s pioneering hip hop practitioners brought them fame amongst their peers, yet the methods of its musical production brought heavy criticism from established musicians. -

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music Elizabeth Medina-Gray KEYWORDS: video game music, modular music, smoothness, probability, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, Portal 2 ABSTRACT: This article provides a detailed method for analyzing smoothness in the seams between musical modules in video games. Video game music is comprised of distinct modules that are triggered during gameplay to yield the real-time soundtracks that accompany players’ diverse experiences with a given game. Smoothness —a quality in which two convergent musical modules fit well together—as well as the opposite quality, disjunction, are integral products of modularity, and each quality can significantly contribute to a game. This article first highlights some modular music structures that are common in video games, and outlines the importance of smoothness and disjunction in video game music. Drawing from sources in the music theory, music perception, and video game music literature (including both scholarship and practical composition guides), this article then introduces a method for analyzing smoothness at modular seams through a particular focus on the musical aspects of meter, timbre, pitch, volume, and abruptness. The method allows for a comprehensive examination of smoothness in both sequential and simultaneous situations, and it includes a probabilistic approach so that an analyst can treat all of the many possible seams that might arise from a single modular system. Select analytical examples from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker and Portal -

Doom.Bethesda.Net

PUBLISHER: Bethesda Softworks DEVELOPER: id Software RELEASE DATE: 22nd November 2019 PLATFORM: Xbox One/PlayStation 4/PC/Nintendo Switch GENRE: First-Person Shooter GAME DESCRIPTION: Developed by id Software, DOOM® Eternal™ is the direct sequel to DOOM®, winner of The Game Awards’ Best Action Game of 2016. Experience the ultimate combination of speed and power as you rip-and-tear your way across dimensions with the next leap in push-forward, first-person combat. Powered by idTech 7 and set to an all-new pulse- pounding soundtrack composed by Mick Gordon, DOOM Eternal puts you in control of the unstoppable DOOM Slayer as you blow apart new and classic demons with powerful weapons in unbelievable and never-before-seen worlds. As the DOOM Slayer, you return to find Earth has suffered a demonic invasion. Raze Hell and discover the Slayer’s origins and his enduring mission to rip and tear…until it is done. FEATURES: Slayer Threat Level at Maximum Gain access to the latest demon-killing tech with the DOOM Slayer’s advanced Praetor Suit, including a shoulder- mounted flamethrower and the retractable wrist-mounted DOOM Blade. Upgraded guns and mods, such as the Super Shotgun’s new distance-closing Meat Hook attachment, and abilities like the Double Dash make you faster, stronger, and more versatile than ever. Unholy Trinity You can’t kill demons when you’re dead, and you can’t stay alive without resources. Take what you need from your enemies: Glory kill for extra health, incinerate for armor, and chainsaw demons to stock up on ammo. -

Martin Stig Anderson

MARTIN STIG ANDERSON SELECTED CREDITS WOLFENSTEIN: YOUNGBLOOD (MachineGames) (2019) CONTROL (Remedy Entertainment) (2019) SHADOW OF THE TOMB RAIDER (Eidos-Montréal) (2018) WOLFENSTEIN II: THE NEW COLOSSUS (MachineGames) (2017) INSIDE (Playdead) (2016) BIOGRAPHY Martin Stig Andersen is a Danish composer best known for his award-winning work within video games. In 2009 he created the audio for Playdead’s video game ‘Limbo’ which won Outstanding Achievement in Sound Design at the InteractiVe Achievement Awards, the IndieCade Sound Award 2010, and was nominated for Use of Audio at the BAFTA Video Games Awards 2011. Following the release of ‘Limbo’, Andersen created and directed the audio for Playdead’s ‘Inside’ which won Best Audio at the Game DeVelopers Choice Awards and has receiVed music and sound design nominations at The Game Awards, The InteractiVe AchieVement Awards and the BAFTA Video Games awards amongst others. In 2017 he composed the score for MachineGames' Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus alongside Mick Gordon which receiVed nominations at The InteractiVe AchieVement Awards, New York Game Awards amongst others. With a background in the fields of acousmatic music, sound installations, electroacoustic performance, and Video art, Martin is known for exploring dynamic relationship between sound and image as a means to reVealing new stories and emotional experiences. His work is often characterized by blurring the dividing line between music and sound design and while he coVers the whole spectrum he is also collaborating with other composers and sound designers in creating unified sound worlds. Being a sought-after speaker, he frequently lectures at conferences such as GDC, DeVelop, and the School of Sound in London. -

Videojuegos, Cultura Y Sociedad

PRESURA VIDEOJUEGOS, CULTURA Y SOCIEDAD NÚMERO XVII MÚSICA Y VIDEOJUEGOS El número XVII, XVII estilo y dirigida a un ni- números de Presura en cho, no aspira a ser un un año. Un número que éxito de masas, pero que no es redondo pero que cada vez seamos más y para mi significa muchí- más es algo a lo que no simo, hemos alcanzado estamos acostumbrados la mayoría de edad. El y nos encanta. Como proyecto no para de cre- sabéis no conseguimos PRESURA cer, estas semanas he- ningún beneficio econó- VIDEOJUEGOS, CULTURA Y SOCIEDAD mos retomado, con éxito, mico con Presura, voso- la actividad en la web. tros, como decía La Cabra Nuestras redes sociales Mecánica, sois nuestra siguen creciendo y todo única riqueza. Sin más, esto es gracias a voso- disfrutad de nuestra ma- tros. Una revista como yoría de edad. Bienveni- Presura, tan ceñida a un dos de nuevo a Presura. ALBERTO VENEGAS RAMOS. Profesor de Histo- al Shams o Témpora Ma- ria en la educación se- gazine y estudiante del cundaria, estudiante de máster Estudios Árabes Antropología Social e e Islámicos Contempo- PRESENTACIÓN investigador en temas ráneos de la Universidad relacionados con la iden- Autónoma de Madrid. tidad en el mundo islá- Colabor de medios como mico además de redactor FS Gamer, CTXT, eldiaro. MÚSICA Y VIDEOJUEGOS. en páginas como Baab es o Akihabara Blues. [email protected] NÚMERO XVII. @albertoxvenegas ATRAVESANDO LA BRECHA VIRTUAL: MÚSICA, VIDEOJUEGOS Y REALIDAD AUMENTADA DE ROBERTO CARLOS FERNÁNDEZ CONTENIDOS: SÁNCHEZ. PÁGINA 16 TRIBUNA - PÁGINA 10 LA MÚSICA Y EL VIDEOJUEGO ABSOLUTO, DE ÍKER GARCÍA ROSO. -

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017 Hosted by Elder Conservatorium of Music, The University of Adelaide. September 28th to October 1st, 2017 Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017, Adelaide, South Australia Keynote Speaker: Professor Takashi Ikegami Published by The Australasian University of Tokyo Computer Music Association Paper & Performances Jury: http://acma.asn.au Stephen Barrass September 2017 Warren Burt Paul Doornbusch ISSN 1448-7780 Luke Dollman Luke Harrald Christian Haines All copyright remains with the authors. Cat Hope Robert Sazdov Sebastian Tomczak Proceedings edited by Luke Harrald & Lindsay Vickery Barnabas Smith. Ian Whalley Stephen Whittington All correspondence with authors should be Organising Committee: sent directly to the authors. Stephen Whittington (chair) General correspondence for ACMA should Michael Ellingford be sent to [email protected] Christian Haines Luke Harrald Sue Hawksley The paper refereeing process is conducted Daniel Pitman according to the specifications of the Sebastian Tomczak Australian Government for the collection of Higher Education research data, and fully refereed papers therefore meet Concert / Technical Support Australian Government requirements for fully-refereed research papers. Daniel Pitman Michael Ellingford Martin Victory With special thanks to: Elder Conservatorium of Music; Elder Hall; Sud de Frank; & OzAsia Festival. DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF COMPUTER MUSIC? COMPUTER MUSIC IN THE AGE OF MACHINE -

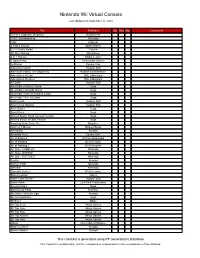

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

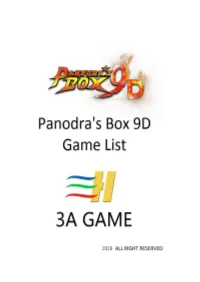

Pandoras Box 9D Arcade Versi

PAGE 1 PAGE 6 1 The King of Fighters 97 51 Cth2003 2 The King of Fighters 98 52 King of Fighters 10Th Extra Plus 3 The King of Fighters 98 Combo Hot 53 Marvel SuperHeroes 4 The King of Fighters 99 54 Marvel Vs. Street Fighter 5 The King of Fighters 2000 55 Marvel Vs. Capcom:Clash 6 The King of Fighters 2001 56 X-Men:Children of the Atom 7 The King of Fighters 2002 57 X-Men Vs. Street Fighter 8 The King of Fighters 2003 58 Street Fighter Alpha:Dreams 9 King of Fighters 10Th UniqueII 59 Street Fighter Alpha 2 10 Cth2003 Super Plus 60 Street Fighter Alpha 3 PAGE 2 PAGE 7 11 The King of Fighters 97 Training 61 Super Gem Fighter:Mini Mix 12 The King of Fighters 98 Training 62 Ring of Destruction II 13 The King of Fighters 98 Combo Training 63 Vampire Hunter:Revenge 14 The King of Fighters 99 Training 64 Vampire Hunter 2:Revenge 15 The King of Fighters 2000 Training 65 Slam Masters 16 The King of Fighters 2001 Training 66 Street Fighter Zero 17 The King of Fighters 2002 Training 67 Street Fighter Zero2 18 The King of Fighters 2003 Training 68 Street Fighter Zero3 19 SNK Vs. Capcom Super Plus 69 Vampire Savior:Lord of Vampire 20 King of Fighters 2002 Magic II 70 Vampire Savior2:Lord of Vampire PAGE 3 PAGE 8 21 King of Gladiator 71 Vampire:The Night Warriors 22 Garou:Mark of the Wolves 72 Galaxy Fight:Universal Warriors 23 Samurai Shodown V Special 73 Aggressors of Dark Kombat 24 Rage of the Dragons 74 Karnodvs Revenge 25 Tokon Matrimelee 75 Savage Reign 26 The Last Blade 2 76 Tao Taido 27 King of Fighters 2002 Super 77 Solitary Fighter 28 King -

The History of Video Game Music from a Production Perspective

Digital Worlds: The History of Video Game Music From a Production Perspective by Griffin Tyler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Bachelor in Arts Music The Colorado College April, 2021 Approved by ___________________________ Date __May 3, 2021_______ Prof. Ryan Banagale Approved by ___________________________ Date ___________________May 4, 2021 Prof. Iddo Aharony 1 Introduction In the modern era of technology and connectivity, one of the most interactive forms of personal entertainment is video games. While video games are arguably at the height of popularity amid the social restrictions of the current Covid-19 pandemic, this popularity did not pop up overnight. For the past four decades video games have been steadily rising in accessibility and usage, growing from a novelty arcade activity of the late 1970s and early 1980s to the globally shared entertainment experience of today. A remarkable study from 2014 by the Entertainment Software Association found that around 58% of Americans actively participate in some form of video game use, the average player is 30 years old and has been playing games for over 13 years. (Sweet, 2015) The reason for this popularity is no mystery, the gaming medium offers storytelling on an interactive level not possible in other forms of media, new friends to make with the addition of online social features, and new worlds to explore when one wishes to temporarily escape from the monotony of daily life. One important aspect of video game appeal and development is music. A good soundtrack can often be the difference between a successful game and one that falls into obscurity. -

A Retrospective Analysis and the Future for Game Music. Bbw Hochschule

Interactive Music writing in the Age of AI: A retrospective analysis and the future for game music. bbw Hochschule – Management of Creative Industries MA Ugur, Huseyin Can Matriculation Number: 037201 Course Code: HM029 Primary supervisor – Peter Mathias Konhäusner Secondary supervisor – Prof. Dr. Ingo Schünemann Submitted on: 26/09/2020 Abstract In this thesis, the practices, workers and monetary aspects of interactive music industry has been investigated. As the terminology regarding this industry is observed to be ambiguous, each of the elements that make up the industry and where they came from were explored. Once the definitions and their relevance to industry have been established, the effects of progressive technology on this industry have been hypothesized. As technologies such as Virtual Reality and Augmented reality are still limited to niche area of console gaming and just recently making their appearance on mainstream, they have been only mentioned. However, with the all-encompassing nature of Artificial Intelligence technologies and what they offer to software industry int this thesis it is hypothesized to impact the industry on its population of workers and their financial and professional practices. As the industry has been observed to be in a stable state financially and dependent on the gaming industry itself, it is proposed that the biggest impact will be in their use of technology and how they can bring new dimensions to future games have been discussed. Furthermore, as these effects have been described anecdotally, to observe the psychosomatic experience a more developed game music can offer, an experiment game based on earlier studies in the field have been conducted.