Mutual Evaluation Report of Hong Kong, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tender Notifications the Table Below Shows Some Recent Tender Notifications from the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government

Tender Notifications The table below shows some recent tender notifications from the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government. The list is NOT exhaustive. *For more information on the Hong Kong SAR Government procurement policy and tender notices of various departments and bureaus, please visithttp://www.fstb.gov.hk/tb/en/government-procurement.htm *To access the electronic tendering services provided by the Government Logistics Department, please visit: http://www.gldetb.gov.hk Points to note: The Issuing Bureau/Department is the responsible party for all matters in relation to the relevant tender issued in the list below. In case of any enquiries about the tender, please contact the relevant Issuing Bureau/Department directly as per the telephone number, fax number or e-mail address listed in the T e n d e r Notice of the respective tender. Closing date (day/month/year) and Goods/Services & Tender Reference Links to further details time for tenders (Hong Kong Time) Tender for the Provision of Remote Site http://www.housingauthority.gov.hk/en/common/pdf/business- 05.01.2017 Monitoring Service (RSMS) for the Hong partnerships/tenders/BP_Tender_Notice_24_Nov_2017_5.pdf (10:00 noon) Kong Housing Authority (Tender reference: HAQ20170472) Supply of bulk foam tender to the Fire https://www.gldpcms.gov.hk/etb_prod/jsp_public/ta/sta00303.jsp? 08.01.2017 services Department, the vehicle to be ready TENDER_REFERENCE_NUMBER=A2500592017 (12:00 noon) to use within 18 months from the date of acceptance of offer (Tender reference: A2500592017) -

Combatting the Opioid Crisis: Exploiting Vulnerabilities in International Mail

United States Senate PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Rob Portman, Chairman Tom Carper,, Ranking Member COMBATTING THE OPIOID CRISIS: EXPLOITING VULNERABILITIES IN INTERNATIONAL MAIL STAFF REPORT PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS UNITED STATES SEENATE COMBATTING THE OPIOID CRISIS: EXPLOITING VULNERABILITIES IN INTERNATIONAL MAIL I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................... 1 A. The Subcommittee’s Investigation .................................................................. 7 B. Findings of Fact and Recommendations ......................................................... 8 II. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................... 13 A. The Opioid Epidemic ...................................................................................... 14 1. Fentanyl and Synthetic Opioids .................................................................... 15 2. The Impact on State and Local Governments ............................................... 16 B. How Fentanyl and Synthetic Opioids Enter the United States ................... 17 1. Sources of Fentanyl ........................................................................................ 17 2. Convenience of Purchasing on the Internet .................................................. 18 3. The Growth of E-Commerce ........................................................................... 19 4. -

CHAPTER 5 Hongkong Post Operation of the Hongkong Post

CHAPTER 5 Hongkong Post Operation of the Hongkong Post Audit Commission Hong Kong 27 October 2015 This audit review was carried out under a set of guidelines tabled in the Provisional Legislative Council by the Chairman of the Public Accounts Committee on 11 February 1998. The guidelines were agreed between the Public Accounts Committee and the Director of Audit and accepted by the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Report No. 65 of the Director of Audit contains 10 Chapters which are available on our website at http://www.aud.gov.hk Audit Commission 26th floor, Immigration Tower 7 Gloucester Road Wan Chai Hong Kong Tel : (852) 2829 4210 Fax : (852) 2824 2087 E-mail : [email protected] OPERATION OF THE HONGKONG POST Contents Paragraph EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1.2 – 1.14 Audit review 1.15 Acknowledgement 1.16 PART 2: MANAGEMENT OF MAIL PROCESSING 2.1 Background 2.2 – 2.3 Underpayment of postage 2.4 – 2.14 Audit recommendations 2.15 Response from the Government 2.16 Procurement of airfreight services 2.17 – 2.28 Audit recommendations 2.29 Response from the Government 2.30 Control and administration of overtime 2.31 – 2.38 Audit recommendations 2.39 Response from the Government 2.40 — i — Paragraph Overtime of Mail Distribution Division 2.41 – 2.54 Audit recommendations 2.55 Response from the Government 2.56 Monitoring of staff regularly working long overtime 2.57 – 2.65 Audit recommendations 2.66 Response from the Government 2.67 PART 3: MANAGEMENT OF POST OFFICES 3.1 – 3.2 Performance -

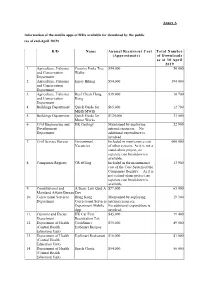

Information of the Mobile Apps of B/Ds Available for Download by the Public (As of End-April 2019)

Annex A Information of the mobile apps of B/Ds available for download by the public (as of end-April 2019) B/D Name Annual Recurrent Cost Total Number (Approximate) of Downloads as at 30 April 2019 1. Agriculture, Fisheries Country Parks Tree $54,000 50 000 and Conservation Walks Department 2. Agriculture, Fisheries Enjoy Hiking $54,000 394 000 and Conservation Department 3. Agriculture, Fisheries Reef Check Hong $39,000 10 700 and Conservation Kong Department 4. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $65,000 12 700 MBIS/MWIS 5. Buildings Department Quick Guide for $120,000 33 000 Minor Works 6. Civil Engineering and HK Geology Maintained by deploying 22 900 Development internal resources. No Department additional expenditure is involved. 7. Civil Service Bureau Government Included in maintenance cost 600 000 Vacancies of other systems. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 8. Companies Registry CR eFiling Included in the maintenance 13 900 cost of the Core System of the Companies Registry. As it is not a stand-alone project, no separate cost breakdown is available. 9. Constitutional and A Basic Law Quiz A $77,000 65 000 Mainland Affairs Bureau Day 10. Correctional Services Hong Kong Maintained by deploying 19 300 Department Correctional Services internal resources. Department Mobile No additional expenditure is App involved. 11. Customs and Excise HK Car First $45,000 19 400 Department Registration Tax 12. Department of Health CookSmart: $35,000 49 000 (Central Health EatSmart Recipes Education Unit) 13. Department of Health EatSmart Restaurant $16,000 41 000 (Central Health Education Unit) 14. -

Special Stamp Issue – “Heartwarming”

Special Stamp Issue – “Heartwarming” Mint Stamps A set of special stamps on the theme of “Heartwarming”, with associated philatelic products, will be released for sale on 11 June 2019 (Tuesday). Sending wishes and blessings to family and friends with Heartwarming stamps has long been popular with the general public. This year, Hongkong Post issues a new set of Heartwarming stamps featuring six stamp designs, four for “Local Mail Postage” and two for “Air Mail Postage”, which are filled with charm and vibrant colours. This makes them an ideal choice for joyous occasions of all kinds. To dovetail with the glittering theme, the “Air Mail Postage” stamps are printed with a hot foil stamping effect, rendering the stamps exceptionally sparkling. The six stamp designs are: Lucky Star (Local Mail Postage) – Cute little origami lucky stars in a glass bottle signify your warmest wishes. Firework (Local Mail Postage) – Magnificent fireworks call to mind the joy of festive times. Love (Local Mail Postage) – A rose in a heart shape conveys your heartfelt love and care for your loved ones. Blessing (Local Mail Postage) – A letter filled with affection brings blessings in abundance. Diamond (Air Mail Postage) – Signifying eternity, diamonds denote your everlasting appreciation. Party (Air Mail Postage) – Dazzling mirror balls reflect the festive atmosphere of an enjoyable party. The denomination of a Heartwarming stamp is represented by the insignia “Local Mail Postage” or “Air Mail Postage”: the “Local Mail Postage” stamps are valid for local small letters weighing 30 grams or less while the “Air Mail Postage” stamps can be used to send small letters by air mail weighing 20 grams or less to any place around the world. -

FCR(2021-22)9 on 7 May 2021

For discussion FCR(2021-22)9 on 7 May 2021 ITEM FOR FINANCE COMMITTEE CAPITAL INVESTMENT FUND HEAD 972 – TRADING FUNDS Subhead 115 Other investments - Post Office Trading Fund Members are invited to approve a commitment of $4,611.3 million as trading fund capital from the Capital Investment Fund to the Post Office Trading Fund to finance the redevelopment of the Air Mail Centre of Hongkong Post. PROBLEM The Government plans to redevelop the Air Mail Centre (AMC) of Hongkong Post (HKP) located at the Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA). With advanced design, expanded capacity equipped with intelligent technologies and up-to-date machineries, the redeveloped AMC will operate with enhanced efficiency in meeting the demand for cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) postal services of the booming e-commerce industry and contributing to developing the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA) as a postal and logistics hub for the country. PROPOSAL 2. We propose to create a commitment to enable the injection of $4,611.3 million as trading fund capital from the Capital Investment Fund (CIF) to the Post Office Trading Fund (POTF) to fund the redevelopment project. The proposed appropriation of funds from the CIF to the POTF will be subject to the approval by the Legislative Council (LegCo) of a resolution to be moved by the Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development. /JUSTIFICATION ….. FCR(2021-22)9 Page 2 JUSTIFICATION Continuous Growth of CBEC 3. The global CBEC has been continuously developing and rapidly expanding in the past decade. Online trading and shopping has become part of the daily life of people and merchants around the world. -

Application Guide for the Cash Allowance Trial Scheme

Application Guide for the Cash Allowance Trial Scheme Contents 1. Eligibility Criteria 2. Procedures for Application and Processing Applications 2.1 Notification Letters and Application Forms 2.2 Update Family Circumstances/Personal Particulars when Completing the Application Form 2.3 Guidance Notes on Completing the Application Form 2.4 Required Documents 2.5 Means of Submitting the Application Form 2.6 Procedures for Processing Applications 3. Arrangements for Disbursement of Allowance 3.1 Amounts of Cash Allowance 3.2 Disbursement of Cash Allowance 3.3 Start Month of Cash Allowance 3.4 Suspension/Adjustment/Cessation of Cash Allowance Disbursement 4. Update Family Circumstances/Personal Particulars when Receiving the Cash Allowance 5. Public Rental Housing General Applicant Households Having Been Waiting for Public Rental Housing for More Than Three Years but Ineligible for the Scheme 6. Reimbursing Underpaid Amount/Recovering Overpaid Amount of Cash Allowance 7. Review 8. Random Checks 9. Personal Data 10. Enquiry Appendix A Sample of Application Form Appendix B Simplified Flowchart of Application for Cash Allowance Appendix C Arrangements for Updating Family Circumstances/ Personal Particulars CAS-AG(E) (06/2021) 1. Eligibility Criteria 1.1 The applicant household under the Cash Allowance Trial Scheme (“the applicant household”) must fulfil all the eligibility criteria set out in the paragraphs below throughout the period of receiving the cash allowance. 1.2 The Cash Allowance Trial Scheme (“the Scheme”) is applicable to the following Public Rental Housing (“PRH”) General Applicant (“GA”) households who have been waiting for PRH – Ordinary Families (i.e. applicant families with two or more persons); or Applicants under the Single Elderly Persons Priority Scheme; or Persons under the Elderly Persons Priority Scheme; or Persons under the Harmonious Families Priority Scheme. -

Chapter 17 Xx1xx Media and Xx2xx Communications

• xxx • xxx • Nano and Advanced Materials Institute. Chapter 17 xx1xx Media and xx2xx Communications 1 foot note 2 Hong Kong’s lively media and world-class foot note telecommunications provide ready access to a wealth 3 foot note of information and entertainment, including the publication of almost 600 daily newspapers and periodicals locally. More than 95 per cent of households are broadband service subscribers and the mobile subscriber penetration rate is about 293 per cent. Hong Kong has one of the most successful telecommunications markets in the world. Fully liberalised and keenly competitive, the market provides a wide range of innovative and advanced telecommunications services to consumers and business users. The city also has a vibrant broadcasting industry, offering a multitude of television and radio channels with diverse programming. Mass Media Hong Kong’s mass media at the end of 2020 included 94 daily newspapers (including electronic newspapers), 500 periodicals, three domestic free-TV programme service licensees, two domestic pay-TV programme service licensees, 10 non-domestic TV programme service licensees, two sound broadcasting licensees and one public service broadcaster. The availability of the latest telecommunications technology and keen interest in Hong Kong’s affairs have attracted many international news agencies, newspapers with international readership and international broadcasters to establish regional headquarters or representative offices here. The production of regional publications in Hong Kong underlines its importance as a financial, industrial, trading and communications centre. Registered Hong Kong-based press at the year-end included 61 Chinese-language dailies, 15 English-language dailies, 15 bilingual dailies and three in Japanese. -

DMM Advisory

August 13, 2020 DMM Advisory Keeping you informed about classification and mailing standards of the United States Postal Service International Service Impacts – Country Suspensions as of August 14, 2020 Effective August 14, 2020, the Postal Service will temporarily suspend international mail acceptance to destinations where transportation is unavailable due to widespread cancellations and restrictions into the area. Customers are asked to refrain from mailing items addressed to the following country, until further notice: • Syria This service disruption affects Priority Mail Express International® (PMEI), Priority Mail International® (PMI), First-Class Mail International® (FCMI), First-Class Package International Service® (FCPIS®), International Priority Airmail® (IPA®), International Surface Air Lift® (ISAL®), and M-Bag® items. Unless otherwise noted, service suspensions to a particular country do not affect delivery of military and diplomatic mail. For already deposited items, other than Global Express Guarantee® (GXG®), Postal Service International Service Center (ISC) employees will endorse the items as “Mail Service Suspended — Return to Sender” and then place them in the mail stream for return. Due to COVID-19, international shipping has been suspended to many countries. According to DMM 604.9.2.3, customers are entitled to a full refund of their postage costs when service to the country of destination is suspended. The detailed procedures to obtain refunds for Retail Postage, eVS, PC Postage, and BMEU entered mail can be found through -

Media and Communications

• xxx • xxx • Nano and Advanced Materials Institute. Chapter 17 xx1xx Media and xx2xx Communications 1 Hong Kong’s lively media and world-class foot note 2 telecommunications provide ready access to a wealth foot note of information and entertainment, including the 3 foot note publication of 611 daily newspapers and periodicals locally. More than 93 per cent of households are broadband service subscribers and the mobile subscriber penetration rate is about 286 per cent. Hong Kong has one of the most successful telecommunications markets in the world. Fully liberalised and keenly competitive, the market provides a wide range of innovative and advanced telecommunications services to consumers and business users. The city also has a vibrant broadcasting industry, offering a multitude of television and radio channels with diversified programming. Mass Media Hong Kong’s mass media at the end of 2019 included 82 daily newspapers (including electronic newspapers), 529 periodicals, three domestic free-TV programme service licensees, two domestic pay-TV programme service licensees, 12 non-domestic TV programme service licensees, two sound broadcasting licensees and one government-funded public service broadcaster. The availability of the latest telecommunications technology and keen interest in Hong Kong’s affairs have attracted many international news agencies, newspapers with international readership and international broadcasters to establish regional headquarters or representative offices here. The production of regional publications in Hong Kong underlines its importance as a financial, industrial, trading and communications centre. Registered Hong Kong-based press at the year end included 53 Chinese-language dailies, 12 English-language dailies, 13 bilingual dailies and four in Japanese. -

Cpos 798FB (08/2020) 1

New Application / Renewal Form for Hongkong Post Bank-Cert (Bank) Certificate Note: (1) Before completing this application, please read the “Certificate Subscriber Agreement” (Annex 1) attached to this application and the “Certification Practice Statement” which can be downloaded from Hongkong Post’s website www.eCert.gov.hk. (2) Please complete this application in English block letters, except where information in Chinese is requested. (3) The Licensed Bank specified in the application form will be the Subscriber of a Hongkong Post Bank-Cert (Bank) certificate. Neither the Authorised Representative nor the Authorized Unit will become the Subscriber. (4) Before submitting this application, please make reference to the “document checklist” (Annex 2) to confirm that all the necessary documents are prepared. (5) Please put a “✔” in the boxes below and complete the sections of this application as indicated. Please select your application type: Action to be applied for (Put a “✔” in the box) Sections of this application to be completed Only New Application A, B & C New and Renewal Application A, B, C & D Only Renewal Application (Authorised Representative remains unchanged) A, B & D Only Renewal Application (Authorised Representative is changed) A, B & D (6) The Authorised Representative is required to submit the application with relevant documents IN PERSON at premises designated by HKPost where a face-to-face authentication of the Authorised Representative’s identity will be conducted. (7) The Authorised Representative may choose to submit the renewal application by mail to Kowloon East Post Office Box No. 68777, Hongkong Post Certification Authority, if his/ her identity has been authenticated in a past application of the Subscriber Licensed Bank at the designated HKPost premises. -

EDBCM16167E.Pdf

EDUCATION BUREAU CIRCULAR MEMORANDUM NO. 167/2016 From : Secretary for Education To : Heads of Kindergartens, Primary and Secondary Schools Ref. : EDB(CD)/ADM/50/1/2(20) Tel. : 2892 6680 Date : 1 November 2016 Curriculum Development Institute Application for Participation in Student Educational Activities and Events (November 2016) (Note: This circular memorandum should be read by heads of all kindergartens, primary and secondary schools) Summary The purpose of this circular memorandum is to invite kindergartens, primary and secondary schools to participate in the coming educational activities and events organised, co-organised or announced by Curriculum Development Institute, Education Bureau. The educational activities and events to be organized include 2017 Xu Beihong Cup International Arts Competition for Youth and Children (Hong Kong), “Library Cards for All School Children” Scheme, The Thirty-fourth Hong Kong Mathematics Olympiad (2016/17), 2016/17 Statistical Project Competition for Secondary School Students, 2016/17 Statistics Creative-Writing Competition for Secondary School Students, Mathematics Project Competition and Mathematics Book Report Competition for Secondary Schools (2016/17), The “Chemists Online” Self-study Award Scheme 2017, The 16th Inter-School Stamp Exhibits Competition and “4.23 World Book Day Creative Competition” in 2017 on “Chinese Culture”. Details 2. The educational activities and events are- a) For kindergartens: Key Learning Title For the attention Remarks Annex Area/ Subject /action of i) Arts Education