Response of Residential Property Values to the Replacement of Limited-Stop Bus Service with Bus Rapid Transit an Analysis of New York City’S Bx12 Select Bus Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

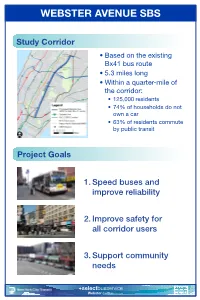

Based on the Existing • Bx41 Bus Route 5.3 Miles Long

WEBSTER AVENUE SBS Study Corridor • Based on the existing Bx41 bus route • 5.3 miles long • Within a quarter-mile of the corridor: • 125,000 residents • 74% of households do not own a car • 63% of residents commute by public transit Project Goals 1. Speed buses and improve reliability 2. Improve safety for all corridor users 3. Support community needs +selectbusservice Webster Avenue BUS DELAY • Bx41 LTD buses are Other 1% stopped more than 50% of Bus Stops the time 24% In Motion • One-way travel time can 49% vary by up to 20 minutes Red Lights (typical times are between 26% 37 and 57 minutes) • Travel times are worst in the PM peak Average Bx41 LTD trip = 46 minutes Bus stops The Hub Fordham Road Red lights Fordham Road Claremont Avenue Congestion E Gun Hill Road Cross Bronx Expressway +selectbusservice Webster Avenue D T R E 221 S S E 220 ST N I E 219 ST E 219 ST A V L A ST E 218 S E V P A N T R 7 S E E 21 A L L B E I V N T T I E 216 S L I O 16 ST E 2 T 15 S H 2 T E E 216 S 5 ST D E 21 W N V 4 ST L E 21 B W A X Y N T L ST E 213 S D Y O E 214 R R L B O P E 212 ST O ST E E T E 213 L S I T W ST S 3 L V 21 ME E ST EN R A D T ST 1 L 211 S V E 212 A 21 TI E R E A C E E 212 ST C E T T T S E B L E L L RD I ILL V P W H T A UN W ST G S 11 E E 2 E N V 1 G E V Y 1 A E 2 A A D E L L E D W L G V T O N S V O A D N A C I I A T A C N N E L H R G A F L T S L O B C M F V V I S P O G Y U N A A L I H T L R N P S C E I E A I M L T D V V A L L D K B N A O A E A L C H A D I T Y N R V L A R V B W V A B T V A L L E M N A U I W U B R N P O L R H U X C O E ST -

Kingsbridge Rd R

Neighborhood Map ¯ 241 3042 239 E 204 Street 3114 3114 3021 Valentine Avenue 3000 201 2 5 E 203 Street Mosholu 3030 Playground Mosholu 359 3039 299 Briggs Avenue E Mosholu Parkway South Parkway Decatur Avenue Bronx Hull Avenue Bx22 Bx1 241 Victory Bx26 Bx22 Bx1 LTD 3028 Memorial Bx28 Bx26 LTD 239 Issac Varian Bx22 Harris Field W4 Bx28 Bx1 306 W20 W4 3030 Bx26 Bx2 School, PS 8 W21 W20 Concourse Yard Bx10 Bx1 E Mosholu Parkway North W21 Villa Avenue Bx2 201 E 202 Street 3001 Mosholu-Pelham Jerome Avenue Greenway 387 3010 Paul Avenue Paul 3013 Goulden Avenue Goulden Bx10 St. Philip Neri 3000 1 W4 Roman Catholic M 6 W20 Church 3010 o W21 Bedford Park 3028 sh o Congregational 340 lu Church Marion Avenue P ar 201 kw E 201 Street E 201 Street311 a Bx22 y 2980 218 Bx26 2980 2998 308 Bedford Park Boulevard West 19 3034 Bainbridge 2990 Avenue 2998 Bx26 Garden 2974 Bedford Park Blvd Bedford Park Blvd Bx34 3000 The APEX 2988 Lehman College Briggs Avenue 326 26 Valentine Avenue Bx34 347 E Mosholu Parkway South 211 Bx41 Bx26 SBS Bedford Park Boulevard Jerome Park 3011 T-3 Building Bx41 Bx41 2950 SBS 375 241 Bainbridge Avenue 2998 Reservoir 3006 2950 360 Bx41 2948 222 Bedford Park 377 High School of 2950 265 Presbyterian Church Webster Avenue American Studies Perry Avenue 15 250 at Lehman College 2948 E 201 Street 2936 2936 Frank 309 399 Speech and 2998 Frisch Field 16 390 Theatre 2948 266 2922 e B 203 e u dfo n rd e E 199 Street St. -

Detailed Report. New Construction Work Paid for out of Corporate Stock

PART 11. DETAILED REPORT. NEW CONSTRUCTION WORK PAID FOR OUT OF CORPORATE STOCK. Shore Road. The contract for the completion of the sea wall along the Shore Road, between Latting Place and Bay Ridge Avenue, and between 92d Street and Fort Hamilton Avenue, which was begun in 1914, was practically completed during 1915. The work consisted of constructing 6,624 linear feet of granite ashlar and concrete sea wall, furnishing and placing 46,000 tons of rip-rap and 350,000 cubic yards of earth fill. The contract for the furnishing and deposit- ing of 250,000 cubic yards of earth fill along the Shore Road, between 94th Street and Fort Hamilton Avenue, was begun during June, 1915. The work of filling in has been more than 50 per cent. completed this year. Dreamland Park. The contract for the construction of seven timber groynes along the beach front of Dreamland Park was completed during May, 1915. The cost of the work was $11,688.60. The purpose has been to stop the washing away of the beach. Records show that since 1874 more than 30 acres of public beach at Coney Island has been lost in this way. At one point, near the foot of the Ocean Boulevard, the Shore line has receded 1,100 feet. Since these groynes have been completed they have protected the beach from erosion and have also reclaimed considerable beach lands. In the spring they will be built up further and more land reclaimed. The contract for the removal of the old timber steamboat pier in front of Dreamland Park was begun during May, 1915. -

Shuttle Service to Mitigate the Impact of Reduced Mass Transit, We Will

Shuttle Service To mitigate the impact of reduced mass transit, we will offer shuttle service to and from certain major sites. Roundtrip service is for Monday – November 5 - from the Outer Boroughs to Manhattan; Outbound 5:30 am – Return begins at 6:30 p.m. Seating is limited and will be provided on a first come, first served basis Shuttles will have a Citibank sign Please be sure to identify yourself as a Citi employee upon boarding the shuttle From/To the Bronx and Queens Bronx Fordham Branch - Shuttle pick-up at corner of E Fordham Road and Creston Road - in front of the Capital One and across from the Citibank Branch. If needed, municipal lot parking available 2 blocks away on Jerome Ave at E Fordham Road. Queens Queensboro Plaza and Queens Plaza MTA Stations - Shuttle pick-up at MTA bus stop at 28th St and Queens Plaza North North Flushing Branch - Shuttle pick-up at the branch; 25-47 Parson Blvd; corner of Parsons Blvd and 25th Drive (Branch has a parking lot) Route Shuttles from Bronx and Queens go to the Mad/42 Branch and then go down Broadway to City Hall Branch with drop-offs at the intersections of Broadway and 34th St, 23rd St, and 14th St before arriving at the City Hall Branch Return Queens- and Bronx-bound shuttles depart City Hall Branch and then go up Sixth Ave with pick-ups at the intersections of Sixth Ave and 14th St, 23rd St, and 34th St before arriving at the Mad/42 Branch and final departure for Queens and Bronx. -

Belton, Frank Interview 1 Belton, Frank

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 10-13-2015 Belton, Frank Interview 1 Belton, Frank. Bronx African American History Project Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Belton, Frank. Interview 1. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham University. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewer: Dr. Mark Naison Interviewee: Frank Belton Session 1 No Date Page 1 Mark Naison: Hello, This is the 53rd interview of The Bronx African American History Project. We’re here with Frank Belton, who was born and raised in Morrisania and for many years was the executive director of the Claremont [inaudible] Associations and is no president and interim track coach of the Pioneer Club. So let’s begin at the beginning. When did your family first move to The Bronx? Frank Belton: We first moved here in January, 1948, from Queens. MN: They moved from Queens? FB: Yeah. MN: And how long had they been living in Queens? FB: About a year. Let me just go back, I was born in Harlem at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. We lived in Harlem for about a year then we moved to Queens for a year, then back to Harlem, Manhattan Avenue, 120th Street. -

By Herbert S. Levinson Icon Mentor Region 2 Urban

NYUWagner 1 NYU • Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service 295 Lafayette Street, 2nd Floor • New York, NY 10012 phone: (212) 998-7545 • fax: (212) 995-4611 www.wagner.nyu.edu/rudincenter Anthony Shorris, Director CATCHING THE NEXT RIDE: THE POTENTIAL FOR REGIONAL BUS RAPID SYSTEMS BUS RAPID TRANSIT FOR THE NEW YORK REGION By Herbert S. Levinson Icon Mentor Region 2 Urban Transportation Research Center City College, New York and Transportation Consultant Wallingford, Connecticut February 24, 2010 2 1. INTRODUCTION Bus rapid transit systems are increasingly being developed throughout the world. In New York City, a comprehensive analysis of options led to New York City Transit implementing Select Bus Service on Fordham Road. A similar service will be installed on First and Second Avenues in Manhattan, Nostrand Avenue in Brooklyn, and Hylan Boulevard in Staten Island. Bus rapid transit proposals have been set forth for Central Ave and I-287 in Westchester County, and a BRT study is underway for Route 110 in Suffolk County. NJ TRANSIT operates BRT service along Springfield and Bloomfield Avenues and is exploring service along several other corridors in Northern New Jersey. The discussion that follows builds upon these actions and proposals to develop the broad outlines of a regional bus rapid transit system for New York City and its environs. The goal is to develop a system that complements and extends the reach of the region’s many rail transit lines. 2. CONTEXT AND ANTECEDENTS Developing a regional bus rapid transit (BRT) system for the New York City region is a challenging and difficult task. -

400 East Fordham Road Bronx, NY Fordham

RETAIL Spaces Available from 400 East Fordham Road 5,066 SF (divisible) up Bronx, NY to 67,314 SF Fordham At the intersection of Fordham Road & Webster Ave Size Neighbors Comments Demographics 5,066 SF - divisible to TJMaxx, Party City, Famous Fordham Place is located at 2018 Estimates 2,303 SF & 2,763 SF Footwear, Starbucks, Chipotle, a major transportation hub 30,752 SF - second floor Applebee’s, Marshalls, Gap, immediately adjacent to the 1 Mile 2 Miles 3 Miles (currently Best Buy) Children’s Place, Verizon bus terminal and Metro North Population 226,725 705,452 1,291,750 31,220 SF - third floor Wireless, Capital One Bank, (formerly 24-Hr Fitness) Game Stop, PC Richard This 14-story retail and Households 73,929 247,253 455,644 commercial building site Co-Tenants is at the intersection of E Median $33,245 $39,139 $42,001 Walgreens, Macy’s Backstage Fordham Rd & Webster Ave, Household Income near Fordham University, is the Daytime 114,155 375,266 704,091 strongest retail corridor in the Population Bronx Contact our exclusive agents: Daniel Glazer Brian Schuster • 5,066 SF - grade (divisible to 2,303 SF & [email protected],763) [email protected] 516.933.8880 516.933.8880 Fordham Place MARKET AERIAL Fordham, BronxBronx, NY ConcourseGrand Plaza WEBSTER AVE BUS FactoryStore SUBWAY FORDHAM ROAD CEE & CEE DEPARTMENT STORE BURGERS FRIES COLAS SUBWAY GRAND CONCOURSE B D Fordham Rd - 3.89M riders annually FORDHAM UNIVERSITY 0062 BX-12 BX-41 BX-12-SBS FORDHAMFORDHAM PLACE PLACE BX-12 BX-12-SBS AVAILABLEAVAILABLE • 5,066 SF• 5,342 (divisible -

MTA 2008 Adopted Budget

III. Major Assumptions 2007-2011 Projections Utilization (Revenue, Ridership, Vehicle Traffic) UTILIZATION Agency Technical Adjustments to Utilization The February Financial Plan utilization levels reflect technical adjustments to the baseline projections that were presented in the November 2007 Financial Plan. These adjustments reflect impacts from the fare and toll increases that were approved by the MTA Board in December 2007, as well as from certain utilization-impacting policy actions and initiatives financed through the Service Enhancement Fund that were also approved by the MTA Board in December1. 2007 Ridership, Traffic and Revenue The 2007 Final Estimate for MTA consolidated ridership is projected to total 2,605 million passengers, while Bridges and Tunnels (B&T) facilities are projected to handle 304 million vehicular crossings. MTA consolidated farebox revenue for the 2007 Final Estimate is estimated to be $3,928 million and toll revenue is estimated to be $1,249 million. These projections of consolidated ridership, vehicular traffic, and fare and toll revenue – based on actual results through September 2007 for MTABC and B&T, and through August 2007 for NYCT, LIRR, MNR, SIR and LIB – are unchanged from the 2007 November Forecast projection. 2008 Ridership, Traffic and Revenue Before factoring in the technical adjustment impacts from the approved 2008 fare and toll increases, as well as those from the service enhancements, the 2008 “baseline” forecasts for ridership, vehicular traffic, and fare and toll revenue remain unchanged from the November Financial Plan’s 2008 Final Proposed Budget. This “baseline” forecast for 2008 MTA consolidated ridership is projected to total 2,648 million passengers, an increase of 44 million trips – a 2% increase – over the 2007 Final Estimate for MTA consolidated ridership. -

1438-20 IBP-OTC Retail Listing V3 SP FINAL WEB 508

Lista de comercios de artículos sin receta (OTC) de Healthfirst Para la lista actualizada de los comercios participantes, por favor visite otcnetwork.com/member 1-888-260-1010 Plan de Beneficios Adicionales (HMO SNP) de Healthfirst TTY 1-888-867-4132, Healthfirst Increased Benefits Plan (HMO SNP) los 7 días de la semana, de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 p.m. (de octubre a marzo), y lunes a viernes, de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 p.m. (de abril a septiembre) Healthfirst.org/medicare H3359_MSD21_38 1438-20_C Your OTC card can be used at any location for the national retailers listed 0123 4567 8901 2345 678 below, as well as the participating IBP retailers listed in this brochure: Su tarjeta de artículos sin receta (OTC) puede usarse en cualquieraBACK de los siguientes establecimientos comerciales a nivel nacional, así como en los comercios participantes que se mencionan dentro del folleto: 您的自選藥物與用品OTC卡可在以下所列的全美零售商家 a tca d a egiste ad a o n t d ng C 0 MDDYY 以及本手冊所列的其他零售商家使用:25 Not : CVSe a d 1/ " Sa Pharmacy y are Dollar General Duane Reade Family Dollar Rite Aid Walgreens Walmart También puede comprar en línea en Nations OTC. Llame al 1-877-236-7027 (TTY 711), de lunes a viernes, de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 p.m., o visite NationsOTC.com/Healthfirst. Tenga a la mano el número de su tarjeta OTC de 19 dígitos. Lista de comercios de artículos sin receta Para la lista más reciente de comercios participantes, (OTC) de Healthfirst para el 2021 por favor visite otcnetwork.com/member CONDADO DEL BRONX 161st St Pharmacy and Agra Pharmacy Best Aid Pharmacy Surgical Supplies 1575 -

East Fordham Road Corridor Safety Improvements 2016

East Fordham Road Corridor Safety Improvements 2016 New York City Department of Transportation Presented by the Office of Research, Implementation and Safety Bronx Community Board 6 on January 21st, 2016 Project Location – Busy retail area – Fordham University, Bronx Botanic Garden, Arthur Ave – Multiple bus lines (Bx12 SBS, B9, B17, B19, B22, B-L 60, 61, 62) Vision Zero Priority Corridor Vision Zero . Multi-agency effort to reduce traffic fatalities in NYC . Borough Action Plans released in 2015 . Priority Intersections, Corridors, and Areas identified for each borough . Fordham Rd, Crotona Ave and Southern Blvd identified as Priority Corridors for the Bronx Why East Fordham Road? • 2010-14: 27 KSI (persons killed or severely injured) • 3 Fatalities (1 pedestrian, 2 motor vehicle occupants) 34 1 34 18 Blvd Southern 45 44 31 2 180 Total Total Fatalities Injuries 2007-2014 2009-2013 Existing Conditions E. Fordham Rd. (between Arthur Ave and Belmont Ave) • Long crossing distances across Fordham Rd. • Heavy pedestrian volumes, commercial activity • Pedestrians crossing outside of marked crosswalks • Existing flush median markings and turn bays 70’ Proposal: E. Fordham Rd. Between Arthur Ave. and Washington Ave Construct 4 pedestrian islands in existing channelization • Islands located at Washington Ave., Arthur Ave., Hoffman Ave., and Lorillard Pl. • No changes to current roadway configuration Existing: E. Fordham Rd. Proposed Condition: Allerton Ave. Proposal: E. Fordham Rd. Between Hughes Ave and Belmont Ave • Extend median into crosswalk with concrete • New signal at Fordham Rd and Belmont Ave under review Existing: E. Fordham Rd. at Hughes Ave. Proposed: Queens Blvd. and 67th Ave. Existing Conditions E. -

Webster Avenue SBS

WEBSTER AVENUE SBS Study Corridor Gun Hill Rd • Based on the existing " " Intermodal Terminal E Gun Hill Rd " Bx41 bus route that " carries 20,000 daily riders " Fordham " Manhattan Plaza Bx12 SBS • 5.3 miles from The Hub A 1 5 " 5 2 4 to Williamsbridge B The Bronx D " • Within a 10-minute walk Webster Ave of the corridor: 6 • 200,000 residents " " Legend • 71% of households do Proposed Webster Ave 3 SBS Corridor (Bx 41 route) The 5 2 Major activity node not own a car Melrose Ave Hub Subway line 3 E 149 St 5 2 6 Bx12 SBS Corridor • 61% of residents NYCT Bus route 4 Metro-North Railroad (MNR) " 5 " commute by public transit 6 MNR Station 0 0.25 0.5 1 I Miles ! ! Project Goals 1. Speed buses and improve reliability 2. Improve safety for all corridor users 3. Support community needs +selectbusservice Webster Avenue BUS DELAY • Bx41 LTD buses are Other 1% stopped more than 50% of Bus Stops the time 24% In Motion • One-way travel time can 49% vary by up to 20 minutes Red Lights (typical times are between 26% 37 and 57 minutes) • Travel times are worst in the PM peak Average Bx41 LTD trip = 46 minutes Bus stops The Hub Fordham Road Red lights Fordham Road Claremont Avenue Congestion E Gun Hill Road Cross Bronx Expressway +selectbusservice Webster Avenue SELECT BUS SERVICE IN NYC Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) A cost-effective approach to transit service that cities around the world have used to make riding the bus more like a subway. -

Nor News Template

Serving Norwood, Bedford Park, Fordham and University Heights NORWOOD NEWS Vol. 25, No. 15 ■ PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION ■ July 26 –August 22, 2012 SUMMER SPLASHING Rangel Emerges Victorious, Part of Bronx Family By ALEX KRATZ Initially, Charlie Rangel wanted nothing to do with the Bronx. The 82-year-old legislative icon, a symbol of black political power and one-time student at DeWitt Clinton High School on Mosholu Parkway, was comfortable with upper Manhattan as his district and Harlem as his base. The Bronx seemed like for - eign territory, not, as it has become, an extension of the dis - trict he had loved and fostered as a Congressman for the last 42 years. “I had a fierce identification with Harlem,” he said in a recent interview, just weeks after edging out a primary victo - ry in the 13th Congressional District, which now includes the northwest Bronx. “As a kid, I always thought if anybody did - Photo by Adi Talwar n’t live in Manhattan, they didn’t live in the City.” BRONXITES HAVE endured record temperatures this summer, but many have found a way to stay cool. He fought the idea that the Bronx would become part of his The Norwood News won’t be publishing again until Aug. 23, but visit our website, norwoodnews.org, for district. But after a judge drew new Congressional lines earli - more photos and news updates. er this year (after the state legislature failed to agree on lines) based on the 2010 Census, it didn’t matter. The Bronx would come to him.