Development Impact on Pokkali Fields a Case of International Container Transshipment Terminal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

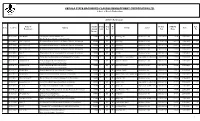

2015-16 Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2015-16 Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 010113918 Anil Kumar Chathiyodu Thadatharikathu Jose 24000 C M R Tailoring Unit Business Sector $84,210.53 71579 22/05/2015 2 Bhavan,Kattacode,Kattacode,Trivandrum 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $52,631.58 44737 18/06/2015 6 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $157,894.74 134211 22/08/2015 7 010114620 Sinu Stephen S Kuruviodu Roadarikathu Veedu,Punalal,Punalal,Trivandrum 48000 C M R Marketing Business Sector $109,473.68 93053 22/08/2015 8 010114661 Biju P Thottumkara Veedu,Valamoozhi,Panayamuttom,Trivandrum 36000 C M R Welding Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 13/05/2015 2 010114682 Reji L Nithin Bhavan,Karimkunnam,Paruthupally,Trivandrum 24000 C F R Bee Culture (Api Culture) Agriculture & Allied Sector $52,631.58 44737 07/05/2015 2 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 22/05/2015 2 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114735 Bijukumar D Sankaramugath Mekkumkara Puthen 36000 C M R Wooden Furniture Business Sector $105,263.16 89474 25/08/2015 3 Veedu,Valiyara,Vellanad,Trivandrum 010114747 Pushpa Bhai Ranjith Bhavan,Irinchal,Aryanad,Trivandrum -

KERALA September 2009

KERALA September 2009 1 KERALA September 2009 Investment climate of a state is determined by a mix of factors • Skilled and cost-effective labour • Procedures for entry and exit of firms • Labour market flexibility • Industrial regulation, labour regulation, • Labour relations other government regulations • Availability of raw materials and natural • Certainty about rules and regulations resources • Security, law and order situation Regulatory framework Resources/Inputs Investment climate of a state Incentives to industry Physical and social infrastructure • Tax incentives and exemptions • Condition of physical infrastructure such as • Investment subsidies and other incentives power, water, roads, etc. • Availability of finance at cost-effective terms • Information infrastructure such as telecom, • Incentives for foreign direct investment IT, etc. (FDI) • Social infrastructure such as educational • Profitability of the industry and medical facilities 2 KERALA September 2009 The focus of this presentation is to discuss… Kerala‘s performance on key socio-economic indicators Availability of social and physical infrastructure in the state Policy framework and investment approval mechanism Cost of doing business in Kerala Key industries and players 3 PERFORMANCE ON KEY SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS Kerala September 2009 Kerala‘s economic performance is driven by the secondary and tertiary sectors Kerala‘s GSDP (US$ billion) • Kerala‘s GDP grew at a CAGR of 13.5 per cent between 1999-00 and 2007-08 to reach US$ 40.4 billion. • The secondary sector has been the fastest growing sector, at a CAGR of 14.5 per cent, driven by manufacturing, construction, electricity, gas and water. • The tertiary sector, the largest contributor to Kerala‘s economy, grew at a rate of 12.5 per cent in 2007-08 over the previous year; it was driven by trade, hotels, real estate, transport and Percentage distribution of GSDP CAGR communications. -

2018040575-1.Pdf

Cooco" mcrud 4 .136430/17 -el5o 11 (3) 6c6na6 cnjl 7 - 6,p&cog; of)o6rD96:eo oflcoroil : 30111117 c6.uC crudec d Ogtl2tZOlS aer Z75})" cnc*a G6.oC oom:cocoem .,crudlci , orcdcruJool€(ooico 04t12t2015 os cru. g(cruc(I)c(a6m ) mcrudM9/2015/ocr.r ,s oiieeeroc"lmqacoo 2013 o6! 6a1 "6oggaejld (r)trc(o)oc(oi cn",q.,..nil.,ocororoilcroo : ,, cnJoc.dlogooJm.dUJlC!ccru@rolCraooJCD:Cruoc.Jcnoru5lcoqggcoo&cCrocas(2013oo cag <a,ggl 30) @ec.dqEg 6e€qos 4o(o)ereua cn1c6q.,r!laoco6 ooo6rDc&Eo esclJ(ro el m, oJ.jl "6 oolccnoooilet om;"u5ctf, co",om:1<if,ncoo cr5lcoraildelacmro5lcncqo, : pcctcoscclqEg ":$acojl<ri ollorcldggg 6oil a<ta o".tcg orgcrLto5rooilml o ^rgccoo , "d.,9il"si oocrieruc5loc$qo Grdcro6DrfitD coco{eeosc1o crjlr8oocemorojlcrocoerrii crooJcoJqo5lBccrDc, Groor.rdjq6rBcc(o)6)cooecmc, eilgc eE€66)'c6tllccu5aca,cmo5icncqo, 2u13 5)s5)er €al 94ogqa:ejlatr cDlcco)actor co"E"r<t5l.,i:cororo5lcrooi| mJcocolcoqo oJcDGoicrrCcnJcdrorcrdo oJfi):ffuoc.Lrcn<oro5lcroqgg GrooJes(o God (2013 oer c6((R Gr6d30) 4-3" o:a.$ (1)-c" g",Loa,qjloo o{ocruoaua6aocrgroaccoil, *iled. 6E€d crc6)e pc.ScuE, roodqeto digcroeL crucQool @(olcc€lc(D ojleLojl<ororonfl q6firgcq ocecrjlcd caccae- ac"n- cmlc"ulrifl m;orcrEm.ll rdcsurcl .,.11. a, agac€ol .Ocm (TuocormoGrD crjlcora" rsEcocrdccn 6cm rt5loilcoilqgg crucBootr @coJco€Jc(o o.ro(Do cnsqspcmoilcroo cruogool @(Dlcoerc(o crilrEq.oem .r.uaooil roqrcocacmoilcroo 4oar,e.ro.gqoroilojlcilecno. Pc @@lco oena' occru<oojlcnao .gdoroilcotccaeneroceml 53ais ecao6rDclsacqo crgq ocmtoro5lafl ggcrrccrd otcEEE(ofl. .Ir$& (ocE6)- - o6c4il - .dlg "Ooemca,g" c6Bcdo- - 15 oicgeo" - ooJflccDo t96 _ cqca' <a<ur!. -

Economic and Social Issues of Biodiversity Loss in Cochin Backwaters

Economic and Social Issues of Biodiversity Loss In Cochin Backwaters BY DR.K T THOMSON READER SCHOOL OF INDUSTRIAL FISHERIES COCHIN UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COCHIN 680 016 [email protected] To 1 The Kerala research Programme on local level development Centre for development studies, Trivandrum This study was carried out at the School of Industrial Fisheries, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Cochin during the period 19991999--2001 with financial support from the Kerala Research Programme on Local Level Development, Centre for Development Studies, Trivandrum. Principal investigator: Dr. K. T. Thomson Research fellows: Ms Deepa Joy Mrs. Susan Abraham 2 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 The specific objectives of our study are 1.3 Conceptual framework and analytical methods 1.4 Scope of the study 1.5 Sources of data and modes of data collection 1.6 Limitations of the study Annexure 1.1 List of major estuaries in Kerala Annexure 1.2 Stakeholders in the Cochin backwaters Chapter 2 Species Diversity And Ecosystem Functions Of Cochin Backwaters 2.1 Factors influencing productivity of backwaters 2.1.1 Physical conditions of water 2.1.2 Chemical conditions of water 2.2 Major phytoplankton species available in Cochin backwaters 2.2.1 Distribution of benthic fauna in Cochin backwaters 2.2.2 Diversity of mangroves in Cochin backwaters 2.2.3 Fish and shellfish diversity 2.3 Diversity of ecological services and functions of Cochin backwaters 2.4 Summary and conclusions Chapter 3 Resource users of Cochin backwaters 3.1 Ecosystem communities of Kochi kayal 3.2 Distribution of population 3.1.1 Cultivators and agricultural labourers. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Eranakulam Rural District from 04.10.2015 to 10.10.2015

Accused Persons arrested in Eranakulam Rural district from 04.10.2015 to 10.10.2015 Name of the Name of Name of the Place at Date & Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police Arresting father of Address of Accused which Time of which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Officer, Rank Accused Arrested Arrest accused & Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kallipparakkudy House, Kothamangalam PS 07.10.15 at 11 1720/15 u/S Kothamangalam Sudheer Manohar station bail Thrikkariyoor P,O, am 279,338 IPC Sub Inspector of Thrikkariyoor Police 1 Manu Prasad Raveendran 28/15 Kothamangalam Chundattu House, Near THQ 07.10.15 at 1750/15 U/S 17 of Kothamangalam Sudheer Manohar JFCM I Mattathipeedika, Elambra Hospital,Kothaman 08.25 pm Kerala Money Sub Inspector of Kothamangalam galam Lenders Act Police 2 Paul Varkey 34/15 Kothamangalam H No: 1040/7, Kannimala Kothamangalam PS 09.10.15 at 01 1674/15 U/S Kothamangalam Sudheer Manohar Estate,Munnar ,Idukki pm 279,337 IPC Sub Inspector of Police 3 Renjithkumar Raji 26/15 Kothamangalam station bail Thandaekkudy Kothamangalam PS 09.10.15 at 7 1766/15 U/S Kothamangalam Sudheer Manohar house,Veliyelchal, pm 447,427,294(b), Sub Inspector of Keerampara 506(i) IPC Police 4 Varghese Peppu 68/15 Kothamangalam station bail Thandaekkudy Kothamangalam PS 09.10.15 at 7 1766/15 U/S Kothamangalam Sudheer Manohar JFCM I house,Veliyelchal, pm 447,427,294(b), Sub Inspector of Kothamangalam Keerampara 506(i) IPC Police 5 Siju Varghese 39/15 Kothamangalam Thandaekkudy Kothamangalam PS 09.10.15 at 7 1766/15 U/S Kothamangalam -

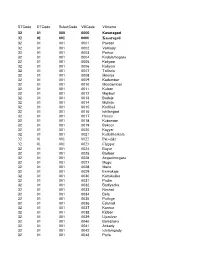

Short Code Rural 32.Xls

STCode DTCode SubdtCode VillCode Villname 32 01 000 0000 Kasaragod 32 01 001 0000 Kasaragod 32 01 001 0001 Pavoor 32 01 001 0002 Vorkady 32 01 001 0003 Pathur 32 01 001 0004 Kodalamogaru 32 01 001 0005 Koliyoor 32 01 001 0006 Kaliyoor 32 01 001 0007 Talikala 32 01 001 0008 Meenja 32 01 001 0009 Kadambar 32 01 001 0010 Moodambail 32 01 001 0011 Kuloor 32 01 001 0012 Majibail 32 01 001 0013 Badaje 32 01 001 0014 Mulinja 32 01 001 0015 Kodibail 32 01 001 0016 Ichilangod 32 01 001 0017 Heroor 32 01 001 0018 Kubanoor 32 01 001 0019 Bekoor 32 01 001 0020 Kayyar 32 01 001 0021 Kudalmarkala 32 01 001 0022 Paivalike 32 01 001 0023 Chippar 32 01 001 0024 Bayar 32 01 001 0025 Badoor 32 01 001 0026 Angadimogaru 32 01 001 0027 Mugu 32 01 001 0028 Maire 32 01 001 0029 Enmakaje 32 01 001 0030 Kattukukke 32 01 001 0031 Padre 32 01 001 0032 Badiyadka 32 01 001 0033 Nirchal 32 01 001 0034 Bela 32 01 001 0035 Puthige 32 01 001 0036 Edanad 32 01 001 0037 Kannur 32 01 001 0038 Kidoor 32 01 001 0039 Ujarulvar 32 01 001 0040 Bombrana 32 01 001 0041 Arikady 32 01 001 0042 Ichilampady 32 01 001 0043 Patla 32 01 001 0044 Kalnad 32 01 001 0045 Perumbala 32 01 001 0046 Thekkil 32 01 001 0047 Muttathody 32 01 001 0048 Pady 32 01 001 0049 Nekraje 32 01 001 0050 Ubrangala 32 01 001 0051 Kumbadaje 32 01 001 0052 Nettanige 32 01 001 0053 Bellur 32 01 001 0054 Adhur 32 01 001 0055 Karadka 32 01 001 0056 Muliyar 32 01 001 0057 Kolathur 32 01 001 0058 Bedadka 32 01 001 0059 Munnad 32 01 001 0060 Kuttikole 32 01 001 0061 Karivedakam 32 01 001 0062 Bandadka 32 01 001 0063 -

Accused Persons Arrested in Ernakulam Rural District from 06.05.2018To12.052018

Accused Persons arrested in Ernakulam Rural district from 06.05.2018to12.052018 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Naduvilaparambil 1599/2018 U/s House, Kanniyankunnu, M V Yacob 1 Subash Krishnan 40/M Seminaripadi Jn 06.05.2018 279 IPC & 185 Aluva East JFCMC I Aluva Ealappadam, U C S I of Police of MV Act Collage, Aluva Thattayil House, Thattadpadi 1600/2018 U/s M V Yacob 2 Joshi Poulose T. O 43/M Bhagam,kanjoor Seminaripadi Jn 06.05.2018 279 IPC & 185 Aluva East JFCMC I Aluva S I of Police Bhagam, Vadakum of MV Act Bhagam Village Manakekad House, 1621/2018 U/s Kuttamessari, M V Yacob 3 Arun Ramanan 21/M Soory Club 08.05.2018 15 ( c ) Abkari Aluva East JFCMC I Aluva Manakeykadu Bhagam, S I of Police Act Keezhmadu, Aluva 1655/2018 U/s Edaparambil House, Jerteena Francis 4 Murukan K K Kunjan 42/M Market Jn 11.05.2018 279 IPC & 185 Aluva East JFCMC I Aluva Asokapuram, Aluva S I of Police of MV Act Vailokuzhy House, 1665/2018 U/s M V Yacob 5 Mohanan Velayudhan 58/M Mupayhadam Kara, Market Jn 12.05.2018 279 IPC & 185 Aluva East JFCMC I Aluva S I of Police Kadungaloor, Aluva of MV Act 1666/2018 U/s Karuna Nivas, Vettiyara Thiruvanathapur Sebastian D 6 Girisankar Mohandas 27/M 12.05.2018 279 IPC & 185 Aluva East JFCMC I Aluva Kara, Navayikulam am S I of Police of MV Act Asariparambil House, 1667/2018 U/s Sebastian D 7 Sudheer Sukumaran 23/M Kaitharam Kara, Ernakulam ( R ) 12.05.2018 279 IPC & 185 Aluva East JFCMC I Aluva S I of Police Kottuvally of MV Act Ettuthengil, Cr. -

Abstract of the Agenda for the Meeting of Rta,Ernakulam Proposed to Be Held on 20-05-2014 at Conference Hall,National Savings Hall,5Th Floor, Civil Station,Ernakulam

ABSTRACT OF THE AGENDA FOR THE MEETING OF RTA,ERNAKULAM PROPOSED TO BE HELD ON 20-05-2014 AT CONFERENCE HALL,NATIONAL SAVINGS HALL,5TH FLOOR, CIVIL STATION,ERNAKULAM Item No.01 G/21147/2014/E Agenda: To consider the application for fresh intra district regular permit in respect ofstage carriage KL-15-4449 to operate on the route Gothuruth-Aluva via Vadakkumpuram,Paravur and U.C College as ordinary service. Applicant:The Managing Director,KSRTC,Tvm Proposed Timings Aluva Paravur Gothuruth A D A D A D 05.15 5.30 6.45 5.45 7.00 8.00 9.10 8.10 9.40 10.25 10.35 11.20 11.30 12.30 1.00 12.45 2.15 1.30 2.25 3.25 4.50 3.50 5.00 6.00 7.25(Halt) 6.10 Item No.02 G/21150/2014/E Agenda: To consider the application for fresh intra district regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15-4377 to operate on the route Gothuruth-Aluva via Vadakkumpuram,Paravur and U.C College as ordinary service. Applicant:The Managing Director,KSRTC,Tvm Proposed Timings Aluva Paravur Gothuruth A D A D A D 6.45 7.00 8.10 7.10 8.20 9.20 10.50 9.50 11.00 11.45 12.00 12.45 12.55 1.10 2.10 2.25 3.35 2.35 4.00 5.00 6.10 5.10 6.20 7.05H Item No.03 G/21143/2014/E Agenda: To consider the application for fresh intra district regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-15-5108 to operate on the route Gothuruth-Aluva via Vadakkumpuram,Paravur and U.C College as ordinary service. -

Thesis Plan V2.Indd

Building with Nature To balance the urban growth of coastal Kochi with its ecological structure P2 Report | January 2013 Delta Interventions Studio | Department of Urbanism Faculty of Architecture |Delft University of Technology Author: Jiya Benni First Mentor: Anne Loes Nillesen Second Mentor: Saskia de Wit Delta Interventions Colophon Jiya Benni, 4180321 M.Sc 3 Urbanism, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands email: [email protected] phone: +31637170336 17 January 2013 Contents 1. Introduction 5. Theoretical Framework 1.1 Estuaries and Barrier Islands 5.1 Building with Nature (BwN) 1.2 Urban growth 5.2 New Urbanism + Delta Urbanism 1.3 Ecological Structure 5.3 Landscape Architecture 5.4 Coastal Zone Management and Integrated Coastal Zone 2. Defi ning the Problem Statement Management 2.1Project Location 2.1.1 History 6. Methodology 2.1.2 Geography 6.1 Literature Review 2.1.3 Demographics 6.2 Site Study 2.1.4 City Structure 6.3 Workshops and Lectures 2.1.5 Morphological Evolution 6.4 Modelling 2.1.6 Importance of the City 6.5 Consultation with Experts 2.2 At the Local Scale 2.2.1 Elankunnapuzha: Past,Preset and Future 7. Societal and Scientifi c Relevance 2.2.2 Elankunnapuzha as a Sub-centre 7.1 What is New? 2.3 Problem Defi nition 7.1.1 Integrating different variables 2.3.1 Background 7.1.2 Geographical Boundaries v/s Political Boundaries 2.3.1.1 New Developments 7.2 Societal Relevance 2.3.1.2 Coastal Issues 7.3 Scientifi c Relevance 2.3.1.3 Ecological Issues 2.3.1.4 Climate Change 8. -

Edappally Music Festival Changampuzha Samskarika Kendram

EDAPPALLY MUSIC FESTIVAL CHANGAMPUZHA SAMSKARIKA KENDRAM Panchayat/ Municipality/ Cochin Corporation Corporation LOCATION District Ernakulam Nearest Town/ Dream Cinemas – 150 m Landmark/ Junction Nearest Bus Station Changampuzha Park Bus Stop – 50 m Nearest Railway Edappally Railway Station – 2.9 Km ACCESSIBILITY Station Nearest Airport Cochin International Airport – 22.9 Km Changampuzha Samskarika Kendram Changampuzha Park, Edapally – 682024 Phone 1: +91-484-2347591 ( 5 pm to 8 pm ) Phone 2: +91-9847853719 CONTACT Email: [email protected] Website: www.changampuzhapark.com DATES FREQUENCY DURATION TIME November Annual 7 Days ABOUT THE FESTIVAL (Legend/History/Myth) The festival is conducted in connection with the annual celebrations of the Edappally Sangeetha Sadas and in honor of Muthaiah Bhagavathar. Edappally Sangeetha Sadas is an organization that caters to the needs of true music lovers and aims at preserving the rich tradition of the classical music which is highly significant for a commercial city like Kochi. Sangeetha Sadas was registered in 2004 under the Charitable Societies Act.The inaugural music concert was held on 15th November 2004traditionally observed as Muthaiah Bhagavatar Day. The annual music festival, Edappally Sangeetholsavam, in which reputed musicians perform, has become an attraction of music lovers from far off places also. Local Above 5000 RELEVANCE- NO. OF PEOPLE (Local / National / International) PARTICIPATED EVENTS/PROGRAMS DESCRIPTION (How festival is celebrated) The Edappally Music Festival is an annual event Carnatic Musical Concerts conducted during November and commences on November 15th, which is observed as the birthday of the Carnatic Musician Muthaiah Bhagavathar. On the first day musical concerts are held in honor of Muthaiah Bhagavathar. -

Department of Industries & Commerce District

Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DEPARTMENT OF INDUSTRIES & COMMERCE DISTRICT INDUSTRIES CENTRE ERNAKULAM POTENTIAL SURVEY REPORT FOR MSME SECTOR Prepared and Published by DISTRICT INDUSTRIES CENTRE KUNNUMPURAM CIVIL STATION ROAD,KAKKANAD,ERNAKULAM PH: 0484-2421432,2421461,FAX – 0484 2421461 E mail- [email protected], [email protected] Web site: www.dic.kerala.gov.in 1 Prepared & Submitted by District Industries Centre,Ernakulam Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District PREFACE An Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District, the industrial capital of Kerala, definitely will be a reflection of the State as a whole. The report is prepared mostly on the basis of available information in different sectors. The survey report reveals the existing industrial scenario of the district and it mainly aims to unveil the potentially disused areas of the industry in Ernakulam. We hope this document will provide guidance for those who need to identify various potential sources/ sectors of industry and thereby can contribute industrial development of the district, and the state. I hereby acknowledge the services rendered by all Managers, Assistant District Industries Officers , Industries Extension Officers ,Statistical Wing and other officers of this office ,for their sincere effort and whole hearted co- operation to make this venture a success within the stipulated time. I am grateful to all the officers of other departments who contributed valuable suggestions and information to prepare this report. General Manager, District Industries Centre, Ernakulam. 2 Prepared & Submitted by District Industries Centre,Ernakulam Industrial Potential Survey of Ernakulam District INDEX Contents Page No Scope & Objectives Methodology Chapter I District at a glance 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Location and extent 1.3 District at a glance 2. -

Tourist Statistics 2019 (Book)

KERALA TOURISM STATISTICS 2019 RESEARCH AND STATISTICS DIVISION DEPARTMENT of TOURISM GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM KERALA TOURISM STATISTICS 2019 Prepared by RESEARCH & STATISTICS DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF TOURISM Sri.KADAKAMPALLY SURENDRAN Minister for Devaswoms, Tourism and Co-Operation, Kerala Ph (Office): 0471-2336605, 2334294 Thiruvananthapuram MESSAGE Kerala is after all India’s most distinguished state. This land of rare natural beauty is steeped in history and culture, but it has still kept up with the times, Kerala has taken its tourism very seriously. It is not for nothing than that the Eden in these tropics; God’s own country was selected by National Geographic Traveler as one of its 50 “destination of life time”. When it comes to building a result oriented development programme, data collection is key in any sector. To capitalize the opportunity to effectively bench mark, it is essential to collect data’s concerned with the matter. In this context statistical analysis of tourist arrivals to a destination is gaining importance .We need to assess whether the development of destination is sufficient to meet the requirements of visiting tourists. Our plan of action should be executed in a meticulous manner on the basis of the statistical findings. Kerala Tourism Statistics 2019 is another effort in the continuing process of Kerala Tourism to keep a tab up-to-date data for timely action and effective planning, in the various fields concerned with tourism. I wish all success to this endeavor. Kadakampally Surendran MESSAGE Kerala Tourism has always attracted tourists, both domestic and foreign with its natural beauty and the warmth and hospitality of the people of Kerala.