Biennials Within the Contemporary Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art

philosophies Article Philosophy in the Artworld: Some Recent Theories of Contemporary Art Terry Smith Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA; [email protected] Received: 17 June 2019; Accepted: 8 July 2019; Published: 12 July 2019 Abstract: “The contemporary” is a phrase in frequent use in artworld discourse as a placeholder term for broader, world-picturing concepts such as “the contemporary condition” or “contemporaneity”. Brief references to key texts by philosophers such as Giorgio Agamben, Jacques Rancière, and Peter Osborne often tend to suffice as indicating the outer limits of theoretical discussion. In an attempt to add some depth to the discourse, this paper outlines my approach to these questions, then explores in some detail what these three theorists have had to say in recent years about contemporaneity in general and contemporary art in particular, and about the links between both. It also examines key essays by Jean-Luc Nancy, Néstor García Canclini, as well as the artist-theorist Jean-Phillipe Antoine, each of whom have contributed significantly to these debates. The analysis moves from Agamben’s poetic evocation of “contemporariness” as a Nietzschean experience of “untimeliness” in relation to one’s times, through Nancy’s emphasis on art’s constant recursion to its origins, Rancière’s attribution of dissensus to the current regime of art, Osborne’s insistence on contemporary art’s “post-conceptual” character, to Canclini’s preference for a “post-autonomous” art, which captures the world at the point of its coming into being. I conclude by echoing Antoine’s call for artists and others to think historically, to “knit together a specific variety of times”, a task that is especially pressing when presentist immanence strives to encompasses everything. -

Cartographies of Conceptual Art in Pursuit of Decentring Sophie Cras

Global Conceptualism? Cartographies of Conceptual Art in Pursuit of Decentring Sophie Cras To cite this version: Sophie Cras. Global Conceptualism? Cartographies of Conceptual Art in Pursuit of Decentring. Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann; Catherine Dossin; Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel. Circulations in the global history of art, Ashgate, pp.167-182, 2015, 9781138295568 1138295566. hal-03192138 HAL Id: hal-03192138 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03192138 Submitted on 12 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Global Conceptualism? Cartographies of Conceptual art in pursuit of Decentering Sophie Cras Conceptual Art had a dual character: on the one hand, the social nature of the work was progressive; on the other, its structural adherence to the avant-garde geography was conservative.1 For the past few years, a recent trend of research has developed aiming to denounce a “Western hegemony” over the history of conceptual art, in favor of a more global conception of this movement. The exhibition Global Conceptualism, held at the Queens Museum of Art in 1999, was one of its major milestones. Against a tradition that viewed conceptual art as an essentially Anglo American movement, the exhibition suggested “a multicentered map with various points of origin” in which “poorly known histories [would be] presented as equal corollaries rather than as appendages to a central axis of activity.”2 The very notion of centrality was altogether repudiated, as Stephen Bann made it clear in his introduction: “The present exhibition .. -

The Conceptual Art Game a Coloring Game Inspired by the Ideas of Postmodern Artist Sol Lewitt

Copyright © 2020 Blick Art Materials All rights reserved 800-447-8192 DickBlick.com The Conceptual Art Game A coloring game inspired by the ideas of postmodern artist Sol LeWitt. Solomon (Sol) LeWitt (1928-2007), one of the key pioneers of conceptual art, noted that, “Each person draws a line differently and each person understands words differently.” When he was working for architect I.M. Pei, LeWitt noted that an architect Materials (required) doesn't build his own design, yet he is still Graph or Grid paper, recommend considered an artist. A composer requires choice of: musicians to make his creation a reality. Koala Sketchbook, Circular Grid, He deduced that art happens before it 8.5" x 8.5", 30 sheets (13848- becomes something viewable, when it is 1085); share two across class conceived in the mind of the artist. Canson Foundation Graph Pad, 8" x 8" grid, 8.5" x 11" pad, 40 He said, “When an artist uses a conceptual sheets, (10636-2885); share two form of art, it means that all of the planning across class and decisions are made beforehand and Choice of color materials, the execution is a perfunctory affair. The recommend: idea becomes a machine that makes the Blick Studio Artists' Colored art.” Pencils, set of 12 (22063-0129); Over the course of his career, LeWitt share one set between two students produced approximately 1,350 designs known as “Wall Drawings” to be completed at specific sites. Faber-Castell DuoTip Washable Markers, set of 12 (22314-0129); The unusual thing is that he rarely painted one share one set between two himself. -

Redalyc.Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: from Pittura

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México AGUIRRE, MARIANA Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917- 1928 Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXXV, núm. 102, 2013, pp. 93-124 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36928274005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative MARIANA AGUIRRE laboratorio sensorial, guadalajara Giorgio Morandi and the “Return to Order”: From Pittura Metafisica to Regionalism, 1917-1928 lthough the art of the Bolognese painter Giorgio Morandi has been showcased in several recent museum exhibitions, impor- tant portions of his trajectory have yet to be analyzed in depth.1 The factA that Morandi’s work has failed to elicit more responses from art historians is the result of the marginalization of modern Italian art from the history of mod- ernism given its reliance on tradition and closeness to Fascism. More impor- tantly, the artist himself favored a formalist interpretation since the late 1930s, which has all but precluded historical approaches to his work except for a few notable exceptions.2 The critic Cesare Brandi, who inaugurated the formalist discourse on Morandi, wrote in 1939 that “nothing is less abstract, less uproot- ed from the world, less indifferent to pain, less deaf to joy than this painting, which apparently retreats to the margins of life and interests itself, withdrawn, in dusty kitchen cupboards.”3 In order to further remove Morandi from the 1. -

Chung Sang-Hwa

CHUNG SANG-HWA Born 1932 Yeongdeok, Korea Lives and works in Gyeonggi-do, Korea Education 1956 B.F.A. in Painting, College of Fine Art, Seoul National University, Seoul Selected Solo Exhibitions 2017 Chung Sang-Hwa: Seven Paintings, Lévy Gorvy, London 2016 Dominique Lévy, New York Greene Naftali, New York 2014 Gallery Hyundai, Seoul 2013 Wooson Gallery, Daegu 2011 Musée d’art Moderne de Saint-Étienne Métropole, Saint-Étienne Gallery Hyundai/Dugahan Gallery, Seoul Dugahun Gallery, Seoul 2009 Gallery Hyundai, Seoul 2008 Galerie Jean Fournier, Paris 2007 Gallery Hyundai, Seoul Gallery Hakgojae, Seoul 1998 Won Gallery, Seoul 1994 Kasahara Gallery, Osaka 1992 Gallery Hyundai, Seoul Shirota Gallery, Tokyo 1991 Ueda Gallery, Tokyo 1990 Kasahara Gallery, Osaka 1989 Gallery Hyundai, Seoul Galerie Dorothea van der Koelen, Mainz 1986 Gallery Hyundai, Seoul 1983 Gallery Hyundai, Seoul Ueda Gallery, Tokyo 1982 Korean Culture Institute, Paris 1980 West Germany Bergheim Culture Institute, Bergheim 1977 Motomachi Gallery, Kobe Coco Gallery, Kyoto 1973 Muramatsu Gallery, Osaka Shinanobashi Gallery, Osaka 1972 Mudo Gallery, Tokyo 1971 Motomachi Gallery, Kobe 1969 Shinanobashi Gallery, Osaka 1968 Jean Camion Gallery, Paris 1967 Press Center Institute Gallery, Seoul 1962 Central Information Institute Gallery, Seoul Selected Group Exhibitions 2016 When Process Becomes Form: Dansaekhwa and Korean Abstraction, Villa Empain, Boghossian Foundation, Brussels Dansaekhwa and Minimalism, Blum & Poe, Los Angeles Dansaekhwa: The Adventure of Korean Monochrome from -

By Arizona Artists Gabriela Muñoz & Claudio Dicochea

FAST FORWARD : a living document un documento vivo by Arizona Artists Gabriela Muñoz & Claudio Dicochea Arizona Latino Arts & Cultural Center/ALAC's mission is the promotion, preservation & education of Latin@ Arts & Culture for our community in the Valley of the Sun. The Center has featured visual and performing artists such as James Garcia and the New Carpa Theater, Oliverio Balcells, Gennaro Garcia, George Yepes, Jim Covarrubias and Reggie Casillas to name a few. 2 Xico Inc is a multidisciplinary arts organization that provides greater knowledge of the cultural and spiritual heritage of Latino and Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Executive Director Donna Valdes initiates vital artistic programming that includes artists like Zarco Guerrero, Carmen de Novais, Joe Ray, Damian Charette, Randy Kemp, Monica Gisel, y Alfredo Manje. 3 Verbo Bala and Arizona Entre Nosotros will feature new works created by Mexican artists in response to current state events, festivals presented in Phoenix, Tucson and Nogales, Sonora during the summer 2011; festival organizers include Michele Ceballos, Adam Cooper-Terán, Laura Milkins, Logan Phillips, Heather Wodrich, and Paco Velez. 4 Raices Taller 222 is Tucson’s only Latino based nonprofit and contemporary art gallery. For many years, it has provided workshops, relevant exhibitions, and cross-disciplinary projects in the historic downtown district. Raices has become a community hub with a long history of social engagement. 5 Mesa Contemporary Arts mission is to inspire people through engaging art experiences that are diverse, accessible, and relevant. The Center has exhibited “Chicanitas” small paintings from the Cheech Marin Collection, “Conexiones” contemporary works by Mexican artists, and “Contemporary Art in Mexico” and “Stations” by Vincent Valdez with Friends of Mexican Arts. -

Digital Engagement in a Contemporary Art Gallery: Transforming Audiences

arts Article Digital Engagement in a Contemporary Art Gallery: Transforming Audiences Clare Harding 1,*, Susan Liggett 2 and Mark Lochrie 3 1 North Wales School of Art & Design, Wrexham Glyndwrˆ University, Wrexham LL11 2AW, UK 2 Media Art and Design Research Centre, Wrexham Glyndwrˆ University, Wrexham LL11 2AW, UK 3 Media Innovation Studio, University of Central Lancashire, Lancashire PR1 2HE, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 8 May 2019; Accepted: 3 July 2019; Published: 11 July 2019 Abstract: This paper examines a curatorial approach to digital art that acknowledges the symbiotic relationship between the digital and other more traditional art practices. It considers some of the issues that arise when digital content is delivered within a public gallery and how specialist knowledge, audience expectations and funding impact on current practices. From the perspective of the Digital Curator at MOSTYN, a contemporary gallery and visual arts centre in Llandudno, North Wales, it outlines the practical challenges and approaches taken to define what audiences want from a public art gallery. Human-centred design processes and activity systems analysis were adopted by MOSTYN with a community of practice—the gallery visitors—to explore the challenges of integrating digital technologies effectively within their curatorial programme and keep up with the pace of change needed today. MOSTYN’s aim is to consider digital holistically within their exhibition programme and within the cannon of 21st century contemporary art practice. Digital curation is at the heart of their model of engagement that offers new and existing audience insights into the significance of digital art within contemporary art practice. -

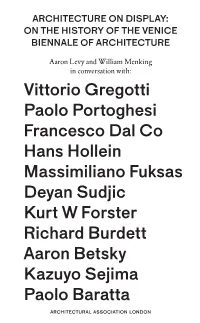

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Monuments to Mundanity at the Socle Du Monde Biennale | Apollo

REVIEWS Monuments to mundanity at the Socle du Monde Biennale Nausikaä El-Mecky 28 APRIL 2017 Socle du Monde (1961), Piero Manzoni. Photo: Ole Bagger. Courtesy of HEART SHARE TWITTER FACEBOOK LINKEDIN EMAIL I am in the middle of nowhere and absolutely terrified. All around me, long strips of white canvas stretch into the distance, suspended above the grass; the wind plays them like strings, making them howl and snap. They are precisely at the level of my neck, and their edges appear razor-sharp. Walking through Keisuke Matsuura’s brilliantly simple Resonance, with its multiple slacklines stretched across two small rises, is like going through a dangerous portal, or navigating a set of laser-beams. Keisuke Matsuura resonance Socle du Monde Biennale 2017 from Keisuke Matsuura on Vimeo. Matsuura’s work is part of the 7th Socle du Monde Biennale in Herning, Denmark. To get there, we drive through an industrial estate in the middle of grey flatlands. Steam billows from a chimney nearby, and a massive hardware store flanks the Biennale’s terrain, which consists of manicured green lawns dotted with several buildings, and intercut by a road or two. Rather than ruining the experience, the encroaching elements of daily life make for a compelling, unpretentious backdrop to the art on display. Matsuura’s work is typical of this Biennale, where things that appear simple, even mundane, suddenly swallow you up in an intense encounter. Even the main building, Denmark’s HEART museum, is a surprise. At first glance it appears to be an unobtrusive, white-walled specimen of Scandi minimalism, but when I happen to look up, I see a beautifully menacing ceiling whose folds and texture resemble parchment or flesh. -

Reynier Leyva Novo

GALLERIA CONTINUA Via del Castello 11, San Gimignano (SI), Italia tel. +390577943134 fax +390577940484 [email protected] www.galleriacontinua.com REYNIER LEYVA NOVO El peso de la muerte Opening: Saturday 13 February 2016, via del Castello 11 and via Arco dei Becci 1, 6pm–12 midnight Until 1 May 2016, Monday–Saturday, 10am–1pm / 2–7pm Galleria Continua is pleased to present the first solo exhibition by Reynier Leyva Novo in Italy. One of the latest generation of Cuban artists, Novo has already had occasion to show his work in important international events and venues such as the Havana Biennial, the Venice Biennale, MARTE Museo de Arte de El Salvador and the Liverpool Biennial. El peso de la muerte is a project specially conceived for Galleria Continua and brings together a series of new works in which investigation and procedure are key elements. Deeply poetic but also alive with questions, Novo’s work is situated in the context of the daily battles to get to the bottom of individual and collective identity. In his artistic practice he moves forward turning his back on the future, penetrating into the most hidden folds of history to offer us a fresh dialogue and a different point of observation. His works are often the result of joint efforts involving historians, cartographers, alchemists, botanists, musicians, designers, translators and military strategists, all engaged in the eternal struggle to gain freedom – individual and collective – , in the attempt to set into motion ideological mechanisms blocked by the rust and sediment that have accumulated over years of immobility and lethargy. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale Di Venezia La Biennale Di Venezia President Presents Roberto Cicutto

LE MUSE INQUIETE WHEN LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA MEETS HISTORY CENTRAL PAVILION, GIARDINI DELLA BIENNALE 29.08 — 8.12.2020 La Biennale di Venezia La Biennale di Venezia President presents Roberto Cicutto Board The Disquieted Muses. Luigi Brugnaro Vicepresidente When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History Claudia Ferrazzi Luca Zaia Auditors’ Committee Jair Lorenco Presidente Stefania Bortoletti Anna Maria Como in collaboration with Director General Istituto Luce-Cinecittà e Rai Teche Andrea Del Mercato and with AAMOD-Fondazione Archivio Audiovisivo del Movimento Operaio e Democratico Archivio Centrale dello Stato Archivio Ugo Mulas Bianconero Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche Fondazione Modena Arti Visive Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea IVESER Istituto Veneziano per la Storia della Resistenza e della Società Contemporanea LIMA Amsterdam Peggy Guggenheim Collection Tate Modern THE DISQUIETED MUSES… The title of the exhibition The Disquieted Muses. When La Biennale di Venezia Meets History does not just convey the content that visitors to the Central Pavilion in the Giardini della Biennale will encounter, but also a vision. Disquiet serves as a driving force behind research, which requires dialogue to verify its theories and needs history to absorb knowledge. This is what La Biennale does and will continue to do as it seeks to reinforce a methodology that creates even stronger bonds between its own disciplines. There are six Muses at the Biennale: Art, Architecture, Cinema, Theatre, Music and Dance, given a voice through the great events that fill Venice and the world every year. There are the places that serve as venues for all of La Biennale’s activities: the Giardini, the Arsenale, the Palazzo del Cinema and other cinemas on the Lido, the theatres, the city of Venice itself.