Thesis Svenia Nowak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AVJ R2066 1,2,3 Now You See Me AVJ R1812 1,2,3, Comptez AVJ R1843

NOM Numéro Editeurs Inventeur 1, 2, 3 Hop là! AVJ R2066 1,2,3 now you see me AVJ R1812 1,2,3, comptez AVJ R1843 1000 bornes AVJ R0302 Dujardin Edmond Dujardin 1000 bornes AVJ R0057 Dujardin Edmond Dujardin 1000 bornes AVJ R0297 Dujardin Edmond Dujardin 18 soldats du feu AVJ R2060 20è siècle AVJ R1542 Iello Vladimír Suchý 22 pommes AVJ R1219 Cocktail games Juan Carlos Pérez Pulido 3 petits cochons (les) AVJ R1951 4 jeux en 1 AVJ R0395 - - 4 jeux en 1 AVJ R0394 - - 6 nimmt junior AVJ R1155 Amigo Wolfgang Kramer 6 qui prend AVJ R0236 Amigo Wofgang Kramer 6 qui prend AVJ R0235 Amigo Wolfgang Kramer 7 familles civilisations anciennes AVJ R1739 7 Wonders AVJ R1352 Repos production Antoine Bauza A dos de chameau AVJ R1342 HABA Hajo Bucken A dos de chameau AVJ R1402 HABA Gabriela Silveira A la carte AVJ R1254 Heidelberger Spieleverlag Karl-Heinz Schmiel A l'abordage AVJ R0715 HABA Guido Hoffmann A l'abordage - le duel AVJ R0757 HABA Guido Hoffmann A l'abordage - le duel AVJ R0756 HABA Guido Hoffmann A l'école des fantômes AVJ R0224 HABA Kai Haferkamp & Markus Nikisch A l'école des fantômes AVJ R1023 HABA Kai Haferkamp & Markus Nikisch Kai Haferkamp A l'école des fantômes - le jeu de cartes AVJ R1392 HABA Markus Nikisch Kai Haferkamp A l'école des fantômes - le jeu de cartes AVJ R1393 HABA Markus Nikisch Inka Brand A l'ombre des murailles AVJ R1088 Filosofia Markus Brand A table les animaux AVJ R1696 Selecta A toute vapeur AVJ R1340 HABA Thilo Hutzler A toute vapeur AVJ R1341 HABA Thilo Hutzler A Toute Vitesse AVJ R0512 HABA Dominique Ehrhard A toute vitesse AVJ R0704 HABA Dominique Ehrhard A Vos Carottes AVJ R0578 HABA Jürgen Elias Laurent Levi Abalone AVJ R0197 Hasbro Michel Lalet Michel Lalet Abalone AVJ R0491 Hasbro Laurent Lévi Michel Lalet Laurent Lévi Michel Lalet Abalone AVJ R0390 Hasbro Laurent Lévi Michel Lalet Abalone (disney) AVJ R0017 - Laurent Lévi Aber bitte mit Sahne AVJ R1156 Winning moves Jeffrey D. -

List of Games Discussed

List of Games Discussed Agricola Number of players: 2–6 Published by: Z-Man Games, Inc. Grade levels: Middle and high Designed by: Uwe Rosenberg school Year published: 2007 Number of players: 1–5 Arthur Saves the Planet: Grade levels: Middle and high One Step at a Time school Published by: FRED Distribution Designed by: Mike Siggins Amun-Re Year published: 2008 Published by: Rio Grande Games Number of players: 2–5 and Hans im Glück Grade levels: Elementary and Designed by: Reiner Knizia middle school Year published: 2003 Number of players: 3–5 Backseat Drawing Grade levels: Middle and high Published by: Out of the Box school Designed by: Catherine Rondeau and Peggy Brown Android Year published: 2008 Published by: Fantasy Flight Games Number of players: 4–10 Designed by: Daniel Clark and Grade levels: Middle and high Kevin Wilson school Year published: 2008 Number of players: 3–5 Bamboleo Grade level: High school Published by: Rio Grande Games and Zoch Verlag Antike Designed by: Jacques Zeimet Published by: Rio Grande Games Year published: 1996 and Eggertspiele Number of players: 2–7 Designed by: Mac Gerdts Grade levels: Middle and high Year published: 2005 school From Libraries Got Game, by Brian Mayer and Christopher Harris (Chicago: American Library Association, 2010). 1 Battlestar Galactica Year published: 2007 Published by: Fantasy Flight Number of players: 2–6 Games Grade levels: Middle and high Designed by: Corey Konieczka school Year published: 2008 Number of players: 3–6 Colosseum Grade level: High school Published by: Days of Wonder Designed by: Markus Lübke and Bausack Wolfgang Kramer Published by: Zoch Verlag Year published: 2007 Designed by: Klaus Zoch Number of players: 3–5 Year published: 1987 Grade levels: Middle and high Number of players: 1–10 school Grade levels: Middle and high school Diplomacy Published by: Avalon Hill Bolide Designed by: Allan B. -

HG100 Base.Qxp

CONTENTS FOREWORD by Reiner Knizia . ix INTRODUCTION by James Lowder . xiii Bruce C. Shelley on Acquire . 1 Nicole Lindroos on Amber Diceless . 5 Ian Livingstone on Amun-Re . 9 Stewart Wieck on Ars Magica . 13 Thomas M. Reid on Axis & Allies . 17 Tracy Hickman on Battle Cry . 21 Philip Reed on BattleTech . 24 Justin Achilli on Blood Bowl . 28 Mike Selinker on Bohnanza . 31 Tom Dalgliesh on Britannia . 34 Greg Stolze on Button Men . 38 Monte Cook on Call of Cthulhu . 42 Steven E. Schend on Carcassonne . 46 Jeff Tidball on Car Wars . 49 Bill Bridges on Champions . 52 Stan! on Circus Maximus . 55 Tom Jolly on Citadels . 58 Steven Savile on Civilization . 62 Bruno Faidutti on Cosmic Encounter . 66 Andrew Looney on Cosmic Wimpout . 69 Skip Williams on Dawn Patrol . 73 Alan R. Moon on Descent . 77 Larry Harris on Diplomacy . 81 Richard Garfield on Dungeons & Dragons . 86 William W. Connors on Dynasty League Baseball . 90 Christian T. Petersen on El Grande . 94 Alessio Cavatore on Empires in Arms . 99 Timothy Brown on Empires of the Middle Ages . 103 Allen Varney on The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen . 107 Phil Yates on Fire and Fury . 110 William Jones on Flames of War . 113 Rick Loomis on Fluxx . 116 John Kovalic on Formula Dé . 119 Anthony J. Gallela on The Fury of Dracula . 122 Jesse Scoble on A Game of Thrones . 126 Lou Zocchi on Gettysburg . 130 James Wallis on Ghostbusters . 134 James M. Ward on The Great Khan Game . 138 Gav Thorpe on Hammer of the Scots . 142 Uli Blennemann on Here I Stand . -

La Storia Componenti Obiettivo Del Gioco Preparazione Del Gioco

Un gioco di Paul Randles, sviluppato da Mike Selinker e Bruno Faidutti. Per 3-5 giocatori. Età da 8 anni in su. LA STORIA L’anno è 1899. Il nuovo secolo albeggia, e con questo la promessa di un futuro ricco. Sei appena venuto a conoscenza che questa piccola isola nei Caraibi era una volta il cuore delle rotte del vecchio mondo dove le navi cadevano preda dei Pirati dei Sette Mari. Molte navi avevano tonnellate di tesori che ora giacciono in attesa di essere recuperati. Il problema è che rimangono solo dieci giorni prima che si scateni l’uragano Ketty. Una volta che la stagione delle tempeste inizia, gli uragani durano per i mesi, rendendo impossibile effettuare immersioni. Il tempo stringe, e tutte le grandi corporazioni del continente arriveranno, e cercheranno di togliere di mezzo gli imprenditori in cerca delle ricchezze nei fondali. Imprenditori come te. Durante i prossimi dieci giorni, ogni giocatore investe nella propria società di immersioni cercando disperatamente di trovare il maggior numero di tesori e di venderli quando i prezzi saranno più alti. COMPONENTI • Un tabellone a due facce che mostra l’isola. • 130 carte, di cui: • 80 carte relitto, di cui: • 20 “shallow water” (poca profondità) • 30 “medium water” (media profondità) • 30 “deep water” (grande profondità) • 5 gruppi di 5 carte azioni, un gruppo per ogni giocatore • 25 carte incontro (usate solo con le regole opzionali) • 15 Tessere Palombaro. • 40 Tessere di Equipaggiamento da palombaro, di cui: • 20 manicotto d’aria • 10 tridente • 10 peso • 1 Tessera ciambella segna giorni. • 1 Tessera segna giocatore iniziale. -

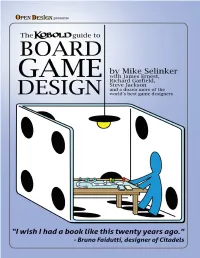

Kobold Guide to Board Game Design Cropped

The Kobold Guide to BOARD GAME DESIGN By Mike Selinker with James Ernest, Richard Garfield, Steve Jackson, and a dozen more of the world’s best designers Table of Contents Credits Foreword Part 1: Concepting The Game Is Not the Rules. By James Ernest Play More Games. By Richard Garfield Pacing Gameplay. By Jeff Tidball Metaphor vs. Mechanics. By Matt Forbeck Whose Game Is It Anyway? By Mike Selinker Part 2: Design How I Design a Game. By Andrew Looney Design Intuitively. By Rob Daviau Come on in and Stay a While. By Lisa Steenson The Most Beautiful Game Mechanics. By Mike Selinker Strategy Is Luck. By James Ernest Let’s Make It Interesting. By James Ernest Part 3: Development Developing Dominion. By Dale Yu Thinking Exponentially. By Paul Peterson Stealing the Fun. By Dave Howell Writing Precise Rules. By Mike Selinker It’s Not Done Till They Say It’s Done. By Teeuwynn Woodruff Part 4: Presentation Amazing Errors in Prototyping. By Steve Jackson Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Prototypes*. By Dale Yu Life’s a Pitch. By Richard C. Levy Getting Your Game Published. By Michelle Nephew Afterword Credits Lead Author and Editor: Mike Selinker Essay Authors: Rob Daviau, James Ernest, Matt Forbeck, Richard Garfield, Dave Howell, Steve Jackson, Richard C. Levy, Andrew Looney, Michelle Nephew, Paul Peterson, Lisa Steenson, Jeff Tidball, Teeuwynn Woodruff, Dale Yu Cover Artist: John Kovalic Proofreader: Miranda Horner Layout: Anne Trent Publisher: Wolfgang Baur The Kobold Guide to Board Game Design © 2011 Open Design LLC All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of this book in any manner without express permission from the publisher is prohibited. -

Ad Astra Rulebook

WELCOME TO THE HOW TO WIN FUTURE! The players' successes in developing their civilization are turned into victory points by THE NEXUS In the far future, Homo Sapiens has slowly means of scoring actions, one of the different DESIGNER adapted to life beyond our planet. The solar actions players may perform. SERIES system has been colonized for centuries now, and over time humans have adapted and changed, The game ends when one player scores 50 effectively evolving into fi ve different races, suited points, or when all planets have been explored. The Nexus Designer for life in different planetary environments. At the end of a round in which either condition Series is a new has been fulfi lled, the game ends and the player collection of original But our star, Sol, is unexpectedly dwindling, with the most victory points is the winner. games created by and it’s now time for humanity to make the renowned designers from fi nal jump, to the stars beyond… all over the world. The COMPONENTS series places a spotlight on In Ad•Astra (“To the Stars”), you will guide the designers themselves. one of the fi ve factions of future humanity in its Inside your box of Ad•Astra you will fi nd the following components: We believe that game exploration of the galaxy. designers deserve more You will travel to stars where you will fi nd — 1 planning board credit than they usually — 150 resource cards, 25 of each resource receive and that more the mysterious artifacts of a long-lost alien information about them civilization. -

Toy and Gift Catalog 2021

1 Toy and Gift Catalog 2021 1 A New Way to Play Asmodee is a worldwide family specializing in game distribution and publishing, with our office located just east of Minneapolis in Roseville, Minnesota. Asmodee USA is one of the largest publishers of tabletop games in the country, with over 3,000 games in our collection, including favorites like Catan, Spot It!, Pandemic, and Ticket to Ride. We distribute titles for players of all ages and interests, from families and friends gathering for a fun evening, to die-hard competitive gamers. When we decided to start a board game company, we had just one goal in mind: bringing people together. Games aren’t mean to put us against each other (despite how fierce the competition may be!), but rather to unite us. We wanted to share the pleasure of playing games together with everyone! To present a variety of different games so people have many ways to play. To create a rich atmosphere of emotions, fun, warmth, and enjoyment. To bring the whole family together with just one game. To offer unique products that are perfect for everyone, from new players to seasoned fanatics. The idea for Asmodee was hatched among friends having fun, and we hope you will have the same experience as you explore our games. Thank you for looking through our catalog, and most importantly, have fun playing! 2 Core Package Benefits of The Core Package Retailers participating in the core package have access to a selection of our best games, as well as exclusive benefits; just for those enrolled in the program*. -

R'gles Key Largo VF Def$

Un jeu développé par Mike Selinker et Bruno Faidutti sur une idée originale de Paul Randles pour 3 à 5 joueurs, âgés de 10 ans ou plus. ous sommes en 1899, et les aventuriers désireux de faire leur entrée dans le XXème siècle à la tête d’une confortable fortune doivent se presser un peu ! Une petite île des Caraïbes, qui se trouvait jadis au croisement des principales routes Nfréquentées par les vaisseaux européens à la grande époque de la flibuste et de la piraterie, va peut-être vous donner l’occasion de faire fortune. C’est en effet par dizaines que galions et caravelles engloutis y reposent sur les fonds marins, et beaucoup abritent des trésors oubliés. Malheureusement, l’ouragan Katty est annoncé pour bientôt, et marquera l’entrée dans la saison des tempêtes, pendant laquelle toute plongée est impossible. Cela ne laisse qu’une dizaine de jours aux aven- turiers que vous êtes pour amasser les trésors des sept mers. Quand la belle saison reviendra, les grandes compagnies seront là, et il n’y aura plus de place pour vous. Dix jours – vous n’avez que dix jours pour faire fortune en gérant au mieux votre maigre capital, en trouvant les plus merveilleux trésors, et en les revendant au meilleur prix. MATÉRIEL BUT DU JEU • Un plateau de jeu en cinq parties, représentant l’île. Votre but est d’être le plus riche à l’issue des dix jours de jeu. Pour cela, • 130 cartes : vous recrutez des scaphandriers que vous envoyez explorer les navires - 80 cartes épaves, dont : engloutis pour ramener des trésors que vous essaierez ensuite de • 20 cartes « faible profondeur ».