The Subliminal and Explicit Roles of Functional Film Music: a Study of Selected Works by Hans Florian Zimmer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immersive Theme Park

THE IMMERSIVE THEME PARK Analyzing the Immersive World of the Magic Kingdom Theme Park JOOST TER BEEK (S4155491) MASTERTHESIS CREATIVE INDUSTRIES Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor: C.C.J. van Eecke 22 July 2018 Summary The aim of this graduation thesis The Immersive Theme Park: Analyzing the Immersive World of the Magic Kingdom Theme Park is to try and understand how the Magic Kingdom theme park works in an immersive sense, using theories and concepts by Lukas (2013) on the immersive world and Ndalianis (2004) on neo-baroque aesthetics as its theoretical framework. While theme parks are a growing sector in the creative industries landscape (as attendance numbers seem to be growing and growing (TEA, 2016)), research on these parks seems to stay underdeveloped in contrast to the somewhat more accepted forms of art, and almost no attention was given to them during the writer’s Master’s courses, making it seem an interesting choice to delve deeper into this subject. Trying to reveal some of the core reasons of why the Disney theme parks are the most visited theme parks in the world, and especially, what makes them so immersive, a profound analysis of the structure, strategies, and design of the Magic Kingdom theme park using concepts associated with the neo-baroque, the immersive world and the theme park is presented through this thesis, written from the perspective of a creative master student who has visited these theme parks frequently over the past few years, using further literature, research, and critical thinking on the subject by others to underly his arguments. -

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest

LEVEL 3 Answer keys Teacher Support Programme Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest Book key g Tia Dalma is speaking to Jack, Will and the pirates EASYSTARTS 1 a arrested about Davy Jones. b rowed h Tia Dalma is speaking to Jack Sparrow about the c chest bottle of earth. d port i Will Turner is speaking to Tia Dalma about saving LEVEL 2 e sword Elizabeth. f governor 10–11 Open answers 12 a Will LEVEL 3 g mast h treasure b on his back i Pirates c the Flying Dutchman j chain d thirteen LEVEL 4 2 Open answers e one hundred 3 Captain Jack Sparrow, Will Turner, Elizabeth Swann, f Tortuga Commodore Norrington / open answers g Gibbs LEVEL 5 4 a Jack Sparrow h Elizabeth b Gibbs i the Compass c Leech j a heart LEVEL 6 d Port Royal 13 a Will goes to the old ship to find the key to the chest. e Will Turner b The old ship won’t move because the water is too f Governor Swann / Bootstrap Bill Turner shallow. h Davy Jones c The Flying Dutchman comes up from the bottom of i Lord Beckett the ocean. j Tortuga d Will stops fighting when someone hits him. 5 a Jack escapes from a prison. e Jones wants one hundred souls for Jack Sparrow’s b He goes to his ship, the Black Pearl. soul. c The monkey is cursed and cannot die. f Jack and Gibbs go to Tortuga to find ninety-nine d Jack Sparrow is searching for a key. -

Pirates of the Caribbean – at World's

LEVEL 3 Teacher’s notes Teacher Support Programme Pirates of the Caribbean – At World’s End to the other world and became committed to hunting EASYSTARTS pirates. Tia Dalma: A mysterious woman who can see into the future and bring people back from the dead. She is really LEVEL 2 Calypso in human form. Sao Feng: A very important Pirate Lord of Singapore. He helps Barbossa, Elizabeth and Will find their way to the LEVEL 3 land of the dead to rescue Jack Sparrow. He believes that Elizabeth is the goddess Calypso in human shape. Bootstrap Bill: Will Turner’s father. He is very loyal to LEVEL 4 the Dutchman’s crew and even attacks his own son when Based on the characters created by Ted Elliot, Terry Rossio, he jumps on board to help Jack. Stuart Beattie and Jay Wolpert. LEVEL 5 Written by Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio. Summary Based on Walt Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean. The letter: The book starts with a letter from Admiral Produced by Jerry Bruckheimer. Brutton which outlines what has happened in the past LEVEL 6 Directed by Gore Verbinski. to all the characters we are going to meet in the book, and which states that Jack Sparrow, a pirate, is a very Character description dangerous man. Captain Jack Sparrow: The central character. He is a very Chapters 1–3: Three pirate ships are attacked by cunning man who always manages to escape from difficult the Flying Dutchman and many pirates are killed. The situations. At the beginning of the book, he is rescued Dutchman’s captain is Davy Jones. -

OPEN SCENARIO the Pirates of the Caribbean

OPEN SCENARIO The Pirates of the Caribbean OPEN SCENARIOS GUIDELINES This programme is delivered in 20 hours ideally divided in sessions of 1 hour each. It is possible to change the structure according to the school’s needs (for example 2 hours sessions or 45 minutes sessions); in any case, the duration and the number of HIIT exercises must be kept as described as any alteration would compromise and invalidate the effectiveness of the sportive training. The total number of hours for the delivery of the programme should not be less than 20. 20 hours divided in: - 1 introductory lesson - 7 episodes (one Open Scenario) to repeat twice (2 hours per episode) = 14 hours - 4 lessons ‘extra’ to be used freely - 1 final lesson (with parents) In order to keep the programme effective and to give the best outcome to all the participants, it is recommended a maximum number of 20 participants per session. SUGGESTED STRUCTURE OF EACH SESSION - Game to know each other and to build the group - Why Theatre and Sport go together: discussion on the meaning and affinity of sport and theatre plus delivery of two games* - Introduction to the Programme* - Introduction to dramatization and improvisation: games and exercise* - Presentation of the Story chosen by teachers (Harry Potter /Jack Sparrow / Peter Pan)* - Introduction to the episode and building of the set in the space with the class - Description of the space from the theatrical perspective. (for example: a ladder is a mountain to climb, a mattress is a lake to swim in it) - Discussion on the outcomes of the episode - Dramatization of the beginning of the episode (for example in Harry Potter: performance of magic, sounds, of magic, words of magic, searching for Harry, calling Harry). -

The Development and Improvement of Instructions

CREATING PROCEDURAL ANIMATION FOR THE TERRESTRIAL LOCOMOTION OF TENTACLED DIGITAL CREATURES A Thesis by SETH ABRAM SCHWARTZ Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Chair of Committee, Tim McLaughlin Committee Members, Philip Galanter John Keyser Head of Department, Tim McLaughlin May 2015 Major Subject: Visualization Copyright 2015 Seth Schwartz ABSTRACT This thesis presents a prototype system to develop procedural animation for the goal-directed terrestrial locomotion of tentacled digital creatures. Creating locomotion for characters with multiple highly deformable limbs is time and labor intensive. This prototype system presents an interactive real-time physically-based solution to procedurally create tentacled creatures and simulate their goal-directed movement about an environment. Artistic control over both the motion path of the creature and the localized behavior of the tentacles is maintained. This system functions as a stand-alone simulation and a tool has been created to integrate it into production software. Applications include use in visual effects and animation where generalized behavior of tentacled creatures is required. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................. -

562849520.Pdf

图书在版编目(CIP)数据 迪士尼英文原版. 加勒比海盗3:世界的尽头 / 美 国迪士尼公司著. — 上海:华东理工大学出版社, 2017.5 (迪士尼丛书) ISBN 978-7-5628-4952-0 Ⅰ.①迪… Ⅱ.①美… Ⅲ.①英语-语言读物 ②长篇 小说-美国-现代 Ⅳ.①H319.4:I 中国版本图书馆CIP数据核字(2017)第047946号 迪士尼英文原版 加勒比海盗3:世界的尽头 Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End 著 者 美国迪士尼公司 项目统筹 戎 炜 责任编辑 朱静梅 芮建芬 责任营销 曹 磊 装帧设计 肖祥德 出版发行 华东理工大学出版社有限公司 地址:上海市梅陇路130号,200237 电话:(021)64250306(营销部) (021)34202391(编辑室) 传真:(021)64252707 网址:www.ecustpress.cn 印 刷 杭州日报报业集团盛元印务有限公司 开 本 787mm×1092mm 1/32 印 张 6.875 字 数 137千字 版 次 2017年5月第1版 印 次 2017年5月第1次 书 号 ISBN 978-7-5628-4952-0 定 价 29.80元 联系我们 电子邮箱:[email protected] 官方微博:e.weibo.com/ecustpress 天猫旗舰店:http://hdlgdxcbs.tmall.com Copyright © 2017 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. Chapter 1 “There be something on the seas that even the most staunch① and bloodthirsty pirates have come to fear. ...” From his spot high in the crow’s nest, a pirate trained his spyglass on the horizon. Nothing. No sign of any ship besides his own and the two they traveled with. The Caribbean Sea was calm, the bright sun sparkling off the ocean waves. Everything was peaceful. So why did he have such a strong sense of foreboding? He lifted his spyglass again. This time he could see a smudge on the horizon. It might be a ship ① staunch adj. 坚强的,坚定的 1 sailing toward them. Worse, it might be an East India Trading Company ship. The pirate knew what would happen if they were taken by Company agents. -

Pirates of the Caribbean

LEVEL 3 Answer keys Teacher Support Programme Pirates of the Caribbean – At World’s End Book key 12 a happy b ten c circles d upside down EASYSTARTS 1 a coins b deck c swords (/cannon, but these are e green f dead g wet h Lord Beckett also guns) d agent e captain f edge i woman 2 Open answers 13 Possible answers: 3 a Jack Sparrow b Davy Jones c Bootstrap Bill a They both want to be captain of the ship. LEVEL 2 d Governor Swann e Tia Dalma f Sao Feng b He doesn’t want to meet the other Pirate Lords. g Calypso c Tai Huang takes Jack and Barbossa back to the Pearl. d He wants to free his father from the Flying LEVEL 3 4 a Davy Jones is speaking to Lord Beckett and his men about the wooden box. Dutchman. b Governor Swann is talking to Davy Jones about his e She can bring the pirates strong winds and smooth daughter, Elizabeth. waters. LEVEL 4 c Tia Dalma is talking to Will and Jack’s sailors about f He thinks that Elizabeth is the goddess Calypso. Barbossa. 14–15 Open answers d Sao Feng is talking to Barbossa and Elizabeth about 16 a 5 b 2 c 6 d 1 e 3 f 4 LEVEL 5 Will Turner. 17 a When Beckett uses the Compass, it points to Jack e Sao Feng is talking to Barbossa about the Brethren Sparrow. Court. b When Sao Feng gives Elizabeth his gold coin, she LEVEL 6 f Will is talking to Sao Feng about Jack Sparrow. -

Celebrations-Issue-29-DV74852.Pdf

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. On the Cover: “Live It Up”, photo © Disney/Cirque du Soleil Issue 29 Live It Up! 42 Contents The Magic and Letters ..........................................................................................6 Mystique of La Nouba Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic by Tim Foster............................................................................16 The Grand Floridian Explorer Emporium by Lou Mongello .....................................................................18 Society Orchestra: 50 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................20 As Time Goes By Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................22 Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................24 -

Representations of Gender Identity in Pirates of the Caribbean Films

OVERLAPPING AND BOUNDARY- BREAKING GENDERS: Representations of gender identity in Pirates of the Caribbean films Bachelor’s thesis Salla Saarnijoki University of Jyväskylä Department of Language and Communication Studies English January 2020 JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO Tiedekunta – Faculty Laitos – Department Humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellinen tiedekunta – Faculty Kieli- ja viestintätieteiden laitos – Department of of Humanities and Social Sciences Language and Communication Studies Tekijä – Author Salla Saarnijoki Työn nimi – Title Overlapping and boundary-breaking genders: Representations of gender identity in Pirates of the Caribbean films Oppiaine – Subject Työn laji – Level Englannin kieli - English Kandidaatin tutkielma – Bachelor’s Thesis Aika – Month and year Sivumäärä – Number of pages Tammikuu 2020 – January 2020 21 Tiivistelmä – Abstract Sukupuoli-identiteettejä on kuvattu erilaisissa teksteissä ja medioissa monella eri tavalla läpi historian. Osa representaatioista on säilynyt tiukemmin, kun taas osa on muuttunut ajan kuluessa ja tekstilajista toiseen. Elokuvat ovat yksi näistä medioista, joissa nykypäivänä voidaan nähdä näitä moninaisia sukupuolten representaatioita. Tämä tutkielma pyrkii löytämään ja analysoimaan näitä sukupuoli-identiteettien representaatioita kolmessa ensimmäisessä Pirates of the Caribbean -elokuvassa. Pyrkimyksenä on myös verrata näitä miehen ja naisen representaatioita keskenään mahdollisten sukupuoliroolien ja valtasuhteiden löytämiseksi. Samalla löydökset voivat paljastaa jotakin vastaavaa maailmasta laajemmallakin -

Coleoid Cephalopods: the Squid, Cuttlefish and Octopus

www.palaeontologyonline.com |Page 1 Title: Fossil Focus — Coleoid cephalopods: the squid, cuttlefish and octopus Author(s): T homas Clements *1 Volume: 8 Article: 6 Page(s): 1-8 Published Date: 01/06/2018 PermaLink: https://www.palaeontologyonline.com/articles/2018/fossil-focus-coleoid-cephalopods-squid-cuttlefi sh-octopus/ IMPORTANT Your use of the Palaeontology [online] archive indicates your acceptance of Palaeontology [online]'s Terms and Conditions of Use, available at h ttp://www.palaeontologyonline.com/site-information/terms-and-conditions/. COPYRIGHT Palaeontology [online] (www.palaeontologyonline.com) publishes all work, unless otherwise stated, under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported (CC BY 3.0) license. This license lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the published work, even commercially, as long as they credit Palaeontology[online] and the author for the original creation. This is the most accommodating of licenses offered by Creative Commons and is recommended for maximum dissemination of published material. Further details are available at http://www.palaeontologyonline.com/site-information/copyright/. CITATION OF ARTICLE Please cite the following published work as: Clements, Thomas. 2018. Fossil Focus — Coleoid cephalopods: the squid, cuttlefish and octopus. Palaeontology Online, Volume 8, Article 6, 1-8. Published by: Palaeontology [online] www.palaeontologyonline.com |Page 2 Fossil Focus — Coleoid cephalopods: the squid, cuttlefish and octopus by T homas Clements *1 What are coleoids? The coleoid cephalopods (Fig. 1), squids, cuttlefish and octopuses 2, are an extremely diverse group of molluscs that inhabits every ocean on the planet. Ranging from the tiny but highly venomous blue-ringed octopus (H apalochlaena) to the largest invertebrates on the planet, the giant and colossal squids (A rchiteuthis and Mesonychoteuthis respectively), coleoids are the dominant cephalopods in modern oceans. -

PIRATES of the CARRIBEAN: DEAD MAN's CHEST Written by Ted Elliott & Terry Rossio Transcript by Nikki M, Dorothy/Silentpawz

PIRATES OF THE CARRIBEAN: DEAD MAN'S CHEST Written by Ted Elliott & Terry Rossio Transcript by Nikki M, Dorothy/silentpawz, Jerome S, Tobias K & Courtney VP. [view looking straight down at rolling swells, sound of wind and thunder, then a low heartbeat] PORT ROYAL [teacups on a table in the rain] [sheet music on music stands in the rain] [bouquet of white orchids, Elizabeth sitting in the rain holding the bouquet] [men rowing, men on horseback, to the sound of thunder] [EITC logo on flag blowing in the wind] [many rowboats are entering the harbor] [Elizabeth sitting alone, at a distance] [marines running, kick a door in] [a mule is seen on the left in the barn where the marines enter] [Liz looking over her shoulder] [Elizabeth drops her bouquet] [Will is in manacles, being escorted by red coats] ELIZABETH SWANN Will...! [Elizabeth runs to Will] ELIZABETH SWANN Why is this happening? WILL TURNER I don't know. You look beautiful. ELIZABETH SWANN I think it's bad luck for the groom to see the bride before the wedding. [marines cross their long axes to bar Governor from entering] [Beckett, in white hair and curls, is standing with Mercer] LORD CUTLER BECKETT Governor Weatherby Swann, it's been too long. LORD CUTLER BECKETT His Lord now... actually. LORD CUTLER BECKETT In fact, I *do*. Mister Mercer! The warrant for the arrest of one William Turner. LORD CUTLER BECKETT Oh, is it? That's annoying. My mistake. Arrest her. ELIZABETH SWANN On what charges? WILL TURNER No! [Beckett takes another document from Mercer, who is standing with Beckett, craggy face and pony tail] LORD CUTLER BECKETT Ah-ha! Here's the one for William Turner. -

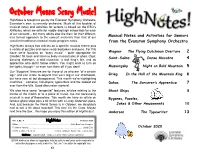

ESO Highnotes October 2020

HighNotes is brought to you by the Evanston Symphony Orchestra, Evanston’s own community orchestra. Much of this booklet of musical notes and activities for seniors is based on the ESO’s KidNotes, which we write for middle and high school kids for each of our concerts – but many adults also like them for their different, less formal approach to the concert materials than that of our Musical Notes and Activities for Seniors excellent traditional classical music program notes. from the Evanston Symphony Orchestra HighNotes always has articles on a specific musical theme plus a variety of puzzles and some really bad jokes and puns. For this issue we’re focusing on “scary music” - quite appropriate for Wagner The Flying Dutchman Overture 2 October! Sit back and listen to lively musical tales of ghost ships, Saint-Saëns Danse Macabre dancing skeletons, a wild mountain, a troll king’s lair, and an 4 apprentice who didn’t follow orders. You might want to turn on the lights, though – or even turn them off if you dare! Mussorgsky Night on Bald Mountain 5 Our “Bygones” features are for those of us who are “of a certain age” and can relate to objects that were big in our childhoods, Grieg In the Hall of the Mountain King 6 but have now all but disappeared. This month we’re highlighting machines – cameras, hair-dryers, typewriters and the coolest car Dukas The Sorcerer’s Apprentice 7 ever from the 60s. Good discussion starters!. We also have some “tangential” features, articles relating to the Ghost Ships 8 theme of the month or to a piece of music, but not necessarily musical in and of themselves.