Professional Chamber Percussion Ensembles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Reich: Music As a Gradual Process Part II Author(S): K

Steve Reich: Music as a Gradual Process Part II Author(s): K. Robert Schwarz Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 20, No. 1/2 (Autumn, 1981 - Summer, 1982), pp. 225-286 Published by: Perspectives of New Music Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/942414 Accessed: 03-10-2018 20:45 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives of New Music This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Wed, 03 Oct 2018 20:45:31 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms STEVE REICH: MUSIC AS A GRADUAL PROCESS PART II K. Robert Schwarz This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Wed, 03 Oct 2018 20:45:31 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms In 1968, Steve Reich codified his compositional aesthetic in the single most important essay he has ever written, "Music as a Gradual Process." This article, which has been reprinted several times,38 must be examined in detail, as it is here that Reich clarifies all the trends that have been developing in his music since 1965, and sets the direction for the future. -

Draft List of Terms for Supplemental Unit and Activities Unit

Further Research for Turkish Music The modern Republic of Turkey is in a part of the world that has been home to many groups of people. Coastal Anatolia was home to the ancient city of Troy, the Greek colonies in Ionia, and the Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire. At its largest, the Ottoman Empire included parts of North Africa, Eastern Europe, Anatolia, and a large area of the Middle East, including Mecca and Medina in the Arabian Peninsula. Because the Ottomans allowed the different peoples living under the Sultan to keep their culture and Religion, they kept their identities. Because of this, people from all of these areas are still living in modern Turkey. Istanbul, the largest and most cosmopolitan city, has populations of Turks, Greeks, Kurds, Arabs, Armenians, Persians, Roma, and Bulgarians, just to name a few. Music is an excellent window into the culture and society of a particular people, or in this case a particular area. We can use many of the topics that come up in talking about music to expand our knowledge of the people who play the music in addition to the music itself. Here, we will explore some of the important terms that came up when we looked at a few of the instruments in Turkey. Some important questions to ask about music and music making: This list is far from complete. It is a good example of the kinds of questions we can ask about music to learn more about it. What: What is the music for? What does the music sound like? What do the players and audiences find important about the music? Who: -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

Rmc193chiprograml5.Pdf

SATURDAY APRIL 29, 2017 | 7:30 PM | ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL A TRIPTYCH: Earth, Moon, Peace Works of Augusta Read Thomas Played by Spektral Quartet and Third Coast Percussion ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL | UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OF UNIVERSITY 2 PROGRAM The program is performed without intermission, although there will be brief pauses for resetting the stage. You are warmly invited to a wine and cheese reception here in the Chapel after the concert, with refreshments served from the west transept. You will also find CDs on sale. RAINBOW BRIDGE TO PARADISE SELENE Moon Chariot Rituals 2016 2015 3 Russell Rolen CELLO Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion and CHI CHI | A TRIPTYCH: EARTH, MOON, PEACE CHI for string quartet RESOUNDING EARTH 2017 World première 2012 I CHI vital life force I INVOCATION pulse radiance II AURA atmospheres, colors, vibrations II PRAYER star dust orbits III MERIDIANS zeniths III MANTRA ceremonial time shapes IV CHAKRAS center of spiritual power in the body IV REVERIE CARILLON crystal lattice Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion Clara Lyon VIOLIN David Skidmore Maeve Feinberg VIOLIN Peter Martin Doyle Armbrust VIOLA Robert Dillon Russell Rolen CELLO Sean Connors ABOUT THIS CONCERT Like most works of art, tonight’s concert came into Enter Spektral Quartet (or re-enter, for this being through the confluence of flashes of desire, conversation also had begun, allegro con spirito, some snippets of conversation, and the sudden alignment of eons before). On March 7, 2015, the cosmic lights went energies sparked by the commissioning of a new work. green and we knew we had a program: Selene, to be The flash of desire came just over three years ago. -

175-Booklet.Pdf

Cover Philip Glass arr. Third Coast Percussion* Philip Glass, arr. Third Coast Percussion* 1 Madeira River (5:43) 15 Xingu River (4:59) Third Coast Percussion Jacob Druckman Paddle to the Sea** (33:57) Reflections on the Nature of Water 2 The Lighthouse and 16 III. Tranquil (2:45) the Cabin (4:23) Robert Dillon 3 Flow (2:34) 17 IV. Gently Swelling (2:09) 4 Open Water (4:19) David Skidmore 5 Thaw (3:36) Philip Glass arr. Third Coast Percussion* 6 The Stewards (2:44) 18 Japurá River (2:57) 7 Niagara (3:20) 8 Sanctuary (5:07) Jacob Druckman 9 The Locks (3:08) Reflections on the Nature of Water 10 Release (1:52) 19 V. Profound (4:35) 11 The Lighthouse (2:54) Robert Dillon Traditional, arr. Musekiwa Chingodza 20 VI. Relentless (2:15) 12 Chigwaya (2:57) Sean Connors Jacob Druckman Philip Glass arr. Third Coast Percussion* Reflections on the Nature of Water 21 Amazon River (9:35) 13 I. Crystalline (2:56) David Skidmore TT: (78:52) 14 II. Fleet (1:52) Peter Martin * from Aguas da Amazonia **World Premiere Recording In building a performance project around this story, the four members of Third Coast Percussion composed music together as a team to perform The protagonist of Holling C. live with the 1966 film adaptation Holling’s 1941 children’s book of Paddle to the Sea — music Paddle to the Sea is a small inspired by, and interspersed wooden figure in a canoe, with, other music that bears lovingly carved by a Native thematic connections to water. -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

KSU School of Music Thanks Our Sponsors

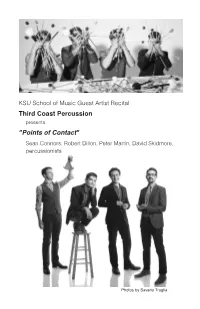

Instruments and Bows KSU School of Music Guest Artist Recital Rentals Third Coast Percussion Repairs presents Stephanie Voss, Certified Master Violin Maker New Making "Points of Contact" 620 Glen Iris Drive, Suite 104 • Atlanta, GA 30308 • 404.876.8617 www.vossviolins.com • [email protected] Sean Connors, Robert Dillon, Peter Martin, David Skidmore, percussionists KSU School of Music Thanks Chastain Road our Located at the corner of Chastain Road & Busbee Parkway Sponsors 770-422-0153 Monday through Saturday 6 am - 10 pm Please join us in showing our appreciation with your support! Photos by Saverio Truglia program program notes Fractalia | Owen Clayton Condon Former Third Coast Percussion member Owen Clayton Condon writes music influenced by minimalism, electronica and taiko drumming. Condon has been commissioned to write music for the 75th anniversary celebration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, and the video and light installation Luminous Field Tuesday, October 20, 2015 at 8:00 pm at Anish Kapoor’s iconic public sculpture Cloud Gate in Chicago’s Millennium Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Park. Twenty-fifth Concert of the 2015-16 Concert Season Fractalia, written for Third Coast Percussion, is a sonic celebration of fractals, geometric shapes whose parts are each a reduced-size copy of the whole OWEN CLAYTON CONDON (b.1978) (derived from the Latin fractus, meaning “broken”). The kaleidoscopic fractured Fractalia (2011) melodies within Fractalia are created by passing a repeated figure through four players in different registers of the marimba. THIERRY DE MEY (b. 1956) Duration: 4 minutes Table Music (1987) Table Music | Thierry De Mey AUGUSTA READ THOMAS (b. -

Hybrid Winds

Hybrid Winds Linsey Pollak When I was about fifteen I had a dream that featured a wind instrument lives on the Sunshine Coast in whose sound I remembered clearly on Queensland and is a renowned waking. It reminded me of a somewhat community music facilitator, mellow crumhorn (Renaissance wind- composer and musical director who capped double reed pipe) or a sort of has built instruments for over 20 high-pitched baritone sax. That sound Figure 1: Gaidanet. years, specialising in aerophones eludes me now, for I have always been chasing that elusive, dreamt, wind- a semitone when it is opened. In fact it from Eastern Europe. He has a instrument sound. only works for the top half of the octave reputation for making and playing I started my instrument making in Macedonian gaidas, but for the full instruments made from rubber journey 25 years ago making bamboo range in Bulgarian gaidas which have a gloves, carrots, watering cans, flutes. That quickly led to a longer stint more conical bore. This enables a unique chairs, brooms, bins and other found of making wooden renaissance flutes, style of playing and ornamentation. objects. His ongoing obsession and an interest in other Renaissance and What I wanted to do was to have combines much of this: making medieval winds. But the real love affair access to the gaida style of playing and ornamentation while playing a lip-blown music more accessible to began 20 years ago with the Macedonian instrument like a clarinet. I experimented communities through instrument gaida (bagpipes), and so I travelled to Macedonia for eight months over three first with a clarinet mouthpiece and a building and playing workshops. -

THE THEATRICAL AESTHETIC of JOHN CAGE by JOYCE RUTH

THE THEATRICAL AESTHETIC OF JOHN CAGE by JOYCE RUTH OZIER B.Sc, Skidmore College, 1963 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Theatre Department We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1979 Q Joyce Ruth Ozier, 1979 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of THEATRE The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 OCTOBER 15, 1979 ii ABSTRACT The topic of this thesis is an analysis of John Cage's aesthetic from a theatrical point of view. I have done this by examining his performed works and his theoretical writings. A short biographical chapter is included in order that the reader may become aware of certain influences and events which have affected his basic ideas. In addition, two short chapters- one on Happenings and another on the Living Theatre- are in• cluded as specific examples of theatrical applications of his aesthetic. It is concluded that Cage's ideas have influenced the general development of recent the• atrical experimentation. -

Instrument Descriptions

RENAISSANCE INSTRUMENTS Shawm and Bagpipes The shawm is a member of a double reed tradition traceable back to ancient Egypt and prominent in many cultures (the Turkish zurna, Chinese so- na, Javanese sruni, Hindu shehnai). In Europe it was combined with brass instruments to form the principal ensemble of the wind band in the 15th and 16th centuries and gave rise in the 1660’s to the Baroque oboe. The reed of the shawm is manipulated directly by the player’s lips, allowing an extended range. The concept of inserting a reed into an airtight bag above a simple pipe is an old one, used in ancient Sumeria and Greece, and found in almost every culture. The bag acts as a reservoir for air, allowing for continuous sound. Many civic and court wind bands of the 15th and early 16th centuries include listings for bagpipes, but later they became the provenance of peasants, used for dances and festivities. Dulcian The dulcian, or bajón, as it was known in Spain, was developed somewhere in the second quarter of the 16th century, an attempt to create a bass reed instrument with a wide range but without the length of a bass shawm. This was accomplished by drilling a bore that doubled back on itself in the same piece of wood, producing an instrument effectively twice as long as the piece of wood that housed it and resulting in a sweeter and softer sound with greater dynamic flexibility. The dulcian provided the bass for brass and reed ensembles throughout its existence. During the 17th century, it became an important solo and continuo instrument and was played into the early 18th century, alongside the jointed bassoon which eventually displaced it. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Third Coast Percussion Presents "Points of Contact" Sean Connors, Robert Dillon, Peter Martin, David Skidmore, Percussionists

KSU School of Music Guest Artist Recital Third Coast Percussion presents "Points of Contact" Sean Connors, Robert Dillon, Peter Martin, David Skidmore, percussionists Photos by Saverio Truglia program Tuesday, October 20, 2015 at 8:00 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Twenty-fifth Concert of the 2015-16 Concert Season OWEN CLAYTON CONDON (b.1978) Fractalia (2011) THIERRY DE MEY (b. 1956) Table Music (1987) AUGUSTA READ THOMAS (b. 1964) Resounding Earth II. Prayer (2012) DAVID SKIDMORE (b. 1982) Trying (2014) Intermission STEVE REICH (b. 1936) Music for Pieces of Wood (1973) TOBIAS BROSTRÖM (b. 1978) Twilight (2001) ALEXANDRE LUNSQUI (b. 1969) Shi (2008) JOHN CAGE (1912-1992) Third Construction (1941) program notes Fractalia | Owen Clayton Condon Former Third Coast Percussion member Owen Clayton Condon writes music influenced by minimalism, electronica and taiko drumming. Condon has been commissioned to write music for the 75th anniversary celebration of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, and the video and light installation Luminous Field at Anish Kapoor’s iconic public sculpture Cloud Gate in Chicago’s Millennium Park. Fractalia, written for Third Coast Percussion, is a sonic celebration of fractals, geometric shapes whose parts are each a reduced-size copy of the whole (derived from the Latin fractus, meaning “broken”). The kaleidoscopic fractured melodies within Fractalia are created by passing a repeated figure through four players in different registers of the marimba. Duration: 4 minutes Table Music | Thierry De Mey Musique de Tables clearly displays Belgian composer and filmmaker Thierry De Mey’s interest in merging the visual and audio aspects of music into a performance art that engages multiple senses.