Journal Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dharmic Environmentalism: Hindu Traditions and Ecological Care By

Dharmic Environmentalism: Hindu Traditions and Ecological Care by © Rebecca Cairns A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, Memorial University, Religious Studies Memorial University of Newfoundland August, 2020 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador ABstract In the midst of environmental degradation, Religious Studies scholars have begun to assess whether or not religious traditions contain ecological resources which may initiate the restructuring of human-nature relationships. In this thesis, I explore whether it is possible to locate within Hindu religious traditions, especially lived Hindu traditions, an environmental ethic. By exploring the arguments made by scholars in the fields of Religion and Ecology, I examine both the ecological “paradoxes” seen by scholars to be inherent to Hindu ritual practice and the ways in which forms of environmental care exist or are developing within lived religion. I do the latter by examining the efforts that have been made by the Bishnoi, the Chipko Movement, Swadhyay Parivar and Bhils to conserve and protect local ecologies and sacred landscapes. ii Acknowledgements I express my gratitude to the supportive community that I found in the Department of Religious Studies. To Dr. Patricia Dold for her invaluable supervision and continued kindness. This project would not have been realized without her support. To my partner Michael, for his continued care, patience, and support. To my friends and family for their encouragement. iii List of Figures Figure 1: Inverted Tree of Life ……………………. 29 Figure 2: Illustration of a navabatrikā……………………. 34 Figure 3: Krishna bathing with the Gopis in the river Yamuna. -

The Possessed Mood of Nonduality in Buddhist Tantric Sex by Anna

MCGILL UNIVERSITY He dances, she shakes: the possessed mood of nonduality in Buddhist tantric sex by Anna Katrine Samuelson A THESIS SUBMITTED TO MCGILL UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS FACULTY OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES MCGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL DECEMBER 2011 © Anna Katrine Samuelson 2011 Table of Contents Table of Contents..………………………………………………………………………………...i Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..…………..…ii Abstrait……………………………………………………………………………..…………….iii Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….................iv INTRODUCTION – VOYEURISM: VIEWING NONDUAL AESTHETICS AND PERFORMANCE IN BUDDHIST RITUAL SEX__________________________________1 Voyeuristic lens: scholarship and methods for viewing tantric sex…………………...…..5 Vajravilasini: the erotic embodiment of nonduality………………………………………7 The siddha poet Lakrminkara……………………………………………………………13 Mingling tantric sex with aesthetics and performance…………………………………..15 CHAPTER 1 – THE FLAVOUR OF THE BUDDHA’S PRESENCE: SAMARASA IN RASA THEORY_____________________________________________________________18 1. Double entendre: sexual and awakening meanings in intention speech………………...20 2. More than a feeling: an introduction to rasa theory…………………………………….25 3. Spngara rasa in siddha poetry and yogini tantras………………………………………29 4. Samarasa: the nondual taste of Buddhist aesthetics…………………………………….39 5. After taste: conclusion…………………………………………………………………...42 CHAPTER 2 – FROM SAMARASA TO SAMAVESA: GENDERED PERFORMANCES OF NONDUAL POSSESSION_________________________________________________44 -

Download: Brill.Com/Brill‑Typeface

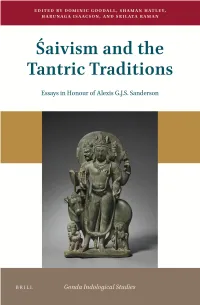

Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions Gonda Indological Studies Published Under the Auspices of the J. Gonda Foundation Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Edited by Peter C. Bisschop (Leiden) Editorial Board Hans T. Bakker (Groningen) Dominic D.S. Goodall (Paris/Pondicherry) Hans Harder (Heidelberg) Stephanie Jamison (Los Angeles) Ellen M. Raven (Leiden) Jonathan A. Silk (Leiden) volume 22 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/gis Alexis G.J.S. Sanderson Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions Essays in Honour of Alexis G.J.S. Sanderson Edited by Dominic Goodall Shaman Hatley Harunaga Isaacson Srilata Raman LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Standing Shiva Mahadeva. Northern India, Kashmir, 8th century. Schist; overall: 53cm (20 7/8in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Bequest of Mrs. Severance A. Millikin 1989.369 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sanderson, Alexis, honouree. | Goodall, Dominic, editor. | Hatley, Shaman, editor. | Isaacson, Harunaga, 1965- editor. | Raman, Srilata, editor. Title: Śaivism and the tantric traditions : essays in honour of Alexis G.J.S. -

Journal Template

The Erotic Imaginary of Divine Realization in Kabbalistic and Tantric Metaphysics In this paper I consider the way in which divinity is realized through an imaginary locus in the mystical thought of Jewish kabbalah and Hindu tantra. It demonstrates a reflective consciousness by the adept or master in understanding the place of God’s being, as a supernal and mundane reality. For the comparative assessment of these two distinctive approaches I shall use as a point of departure the interpretative strategies employed by Elliot R. Wolfson in his detailed work on Jewish mysticism. He argues that there is an androcentric bias embedded in the speculative outlook of medieval kabbalah, as he reads the texts through a psychoanalytic lens. In a similar way, I will argue that there is an androcentric bias to the speculations presented in medieval Śaiva tantra, in particular that division known as the Trika. Overall, my aim is to suggest some functional and perhaps structural similarities to the characterization of divinity in these two traditions, through brief analyses of the erotic understanding of the nature of the Godhead. Introduction In the Jewish view, the orthodox understanding of God is one of distant immutability and ‘unmovedness’.1 For their part, kabbalists follow this view of positing a God that is endlessly ultimate, as a void that is beyond conception, which they call Ein Sof, and which is apophatically dark; this means that Ein Sof is hidden from direct human perception.2 In order to bridge the gulf between God and human beings kabbalists consequently elaborate the idea of a dynamic realization of divinity, an immanent fullness that is conceptualizable (to an extent at any rate). -

The Power of Tantra

P1: KDP Trim: 156mm × 234mm Top: 0.625in Gutter: 0.875in IBBK001-FM IBBK001/Hugh ISBN: 978 1 84511 873 0 September 21, 2009 17:39 THE POWER OF TANTRA Hugh B. Urban is Professor of Comparative Studies at Ohio State University. One of the leading Western scholars of Tantric religion, Professor Urban is the author of several books which include Magia Sexualis: Sex, Magic and Liberation in Modern Western Esotericism (2006), Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics and Power in the Study of Religion (2003), and Songs of Ecstasy: Tantric and Devotional Songs from Bengal (2001). “The Power of Tantra is a major scholarly treatment of a much misconstrued esoteric tradition and a well-written and illustrated guide to a dimension of Hinduism that deserves the careful research Hugh B. Urban has given it. An impressive achievement.” – Paul B. Courtright, Professor of Religion and Asian Studies, Emory University “Building on his extraordinary knowledge of the Sanskrit, Bangla, and As- samese sources, Hugh B. Urban flies straight into the heart of the raging controversy over the sex and violence of Tantra: Is this an Orientalist fan- tasy, or a Hindu nightmare, or a profound religious phenomenon? Drawing richly upon previously untapped texts and new fieldwork, Urban boldly and creatively takes the arguments about Tantra in an entirely new direction, re- vealing aspects of the worship of the goddess that have deep meaning for Hindus and great potential power even for the heirs of Orientalism.” – Wendy Doniger, Mircea Eliade Distinguished Service Professor of the History of Religions, University of Chicago “Once again, Hugh B.