Transferability of Policies and Organisational Practices Across Public and Private Health Service Delivery Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trauma Care – the Eastern Cape Story

GUEST EDITORIAL Trauma care – the Eastern Cape story While I am writing this editorial, the bloodshed seen disciplines at the East London Hospital Complex produced a book, in the casualty, emergency and trauma units across Surgery Survival Guide. What started as a 50-page document in 2013, the Eastern Cape province still harbours fresh in my has grown to a 200-page surgical handbook in 2015, focusing purely memory. on the management of common surgical emergencies, including An estimated 48 000 South Africans are killed as trauma, general surgery, neurosurgery, urology, paediatric surgery, a result of trauma-related events annually, with a further 3.5 million orthopaedics and intensive care. With the aid of funding from the seeking healthcare as a result of trauma.[1,2] South Africa (SA)’s injury provincial department of health, the book is now widely circulated death rate is nearly twice the global average.[3] Rising levels of poverty across all health facilitates in the province. The text is very much a and unemployment, limited access to education, abuse of alcohol and work in progress and it needs to be seen whether it will stand the test drugs, widespread access to firearms and other weapons, exposure of time … but Rome was not built in a day. to violence in childhood and a weak culture of enforcement are The Guide is just one of the initiatives and changes that needs to just a few of the multiple factors contributing to this carnage. The take place to improve trauma care in the province. Emphasis needs government has implemented programmes and campaigns to address to be placed on every level of care – encouraging personnel to work these issues. -

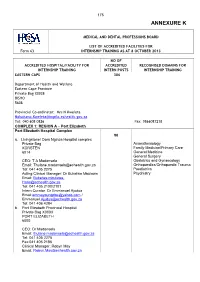

2017 in – Handbook-ANNEXURE K

175 ANNEXURE K MEDICAL AND DENTAL PROFESSIONS BOARD LIST OF ACCREDITED FACILITIES FOR Form 63 INTERNSHIP TRAINING AS AT 8 OCTOBER 2013 NO OF ACCREDITED HOSPITAL/FACILITY FOR ACCREDITED RECOGNISED DOMAINS FOR INTERNSHIP TRAINING INTERN POSTS INTERNSHIP TRAINING EASTERN CAPE 306 Department of Health and Welfare Eastern Cape Province Private Bag X0038 BISHO 5608 Provincial Co-ordinator: Mrs N Kweleta [email protected] Tel: 040 608 0826 Fax: 0866087218 COMPLEX 1: REGION A – Port Elizabeth Port Elizabeth Hospital Complex 90 a. Livingstone/ Dora Nginza Hospital complex Private Bag Anaesthesiology KORSTEN Family Medicine/Primary Care 6014 General Medicine General Surgery CEO: T A Madonsela Obstetrics and Gynaecology Email: [email protected] Orthopaedics/Orthopaedic Trauma Tel: 041 405 2275 Paediatrics Acting Clinical Manager: Dr Bukelwa Mbulawa Psychiatry Email: Bukelwa.mbulawa- [email protected] Tel: 041 405 2100/2101 Intern Curator: Dr Emmanuel Ajudua Email:[email protected] / [email protected] Tel: 041 406 4284 b. Port Elizabeth Provincial Hospital Private Bag X0003 PORT ELIZABETH 6000 CEO: Dr Madonsela Email: [email protected] Tel: 041 405 2275 Fax:041 405 2186 Clinical Manager: Robyn May Email: [email protected] 176 NO OF ACCREDITED HOSPITAL/FACILITY FOR ACCREDITED RECOGNISED DOMAINS FOR INTERNSHIP TRAINING INTERN POSTS INTERNSHIP TRAINING Uitenhage Provincial Hospital Private Bag X36 30 Anaesthesiology UITENHAGE Family Medicine/Primary Care 6630 General Medicine General Surgery CEO: Ms Klassen Obstetrics and Gynaecology Email: [email protected] Orthopaedics/Orthopaedic Trauma Tel: 041 995 1130 Paediatrics Fax: 041 9661413 Psychiatry Clinical Manager: Dr G B Walsh Email: [email protected] Tel: 041 995 1130 Intern Curator: Dr F Zietsman Email: [email protected] Tel: 041 995 1356 COMPLEX 2: REGION B – None COMPLEX 3: REGION C – East London East London Hospital Complex 108 a. -

Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No

76 No.32308 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 11 JUNE 2009 No. R. 664 11 ..June 2009 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY DENTISTS IN THE YEAR 2010 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of dentistry. DISTRICT FACILITY All Hospital Butterworth Hospital Cathcart Hospital Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cradock Hospital Dimbaza CHC Fort Beaufort Hospital * Frere Hospital Frontier Hospital Glen Grey Hospital Madwaleni Hospital SS Gida Hospital Tafalofefe Hospital Zitulele Alfred Nzo Maluti CHC : Mt Ayjff Hospital I Sipetu Hospital . T uest H Cacadu Graaf Reinet CHC Humansdorp Hospital Port Alfred Hospital Settlers I AIDSSt HELPLINE 0000-01·23-22 STAATSKOERANT, 11 JUNIE 2009 No.32308 77 O.R. Tambo Bambisana Hospital ISRDS NODE Canzibe Hospital Greenville Hospital ** Holycross Hospital ** Isilimela Hospital Mhlakulo CHS ** Mthatha General Hospital ** Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital Nessie Knight Hospital ** Ngangelizwe CHS ** St Barnabas Hospital FREE STATE Xhariep District Area Diamond Clinic" (DC Embekweni/Stoffel Coetzee Hospital* Petrusburg CHC* Motheo District National District Hospital (DC17) , Lejweleputswa District Welkom Hospital Area (DC18) Thabo Mafutsanyane Mofumahadi Manapo Mopeli Complex ** District (DC19) Phekolong Complex ** ISRDS NODE Thebe Hospital** Phumelela Hospital ** Fezile Dabi District Kroonstad -

Medical and Dental Professions Board

HEALTH PROFESSIONS COUNCIL OF SOUTH AFRICA MEDICAL AND DENTAL PROFESSIONS BOARD HANDBOOK ON INTERNSHIP TRAINING GUIDELINES FOR INTERNS, ACCREDITED FACILITIES AND HEALTH AUTHORITIES PRETORIA 2021 EDITION PREFACE On behalf the Medical and Dental Professions Board (MDB), I have the pleasure of making this Handbook available to all Interns, Intern Curators, and Accredited Facilities for Internship Training and Health Authorities who are involved with internship training and who employ interns. The Board has come to appreciate the need in practice to obtain clear guidelines for internship training. Thus, based on experiences of Board members, Evaluators of Internship Training and inputs of those who went through Internship Training, this Handbook for Internship Training has been revised and we trust that it will be relevant as a guideline that will serve the needs of Interns and those responsible for their training. The Medical and Dental Professions Board looks forward to ongoing improvement in the nature and quality of internship training as part of its role and mission of “Protecting the Public and Guiding the Professions”. Part of this improvement is through the feedback and inputs from all our interns during their internship training. As of January 2020, Internship training model has been modified to incorporate six months of training in the primary health platform in the second year. The training will be for 24 months with specific domains to be completed in the first year before proceeding to the domains of second year. This has resulted in the expansion of existing training platform incorporating the district health system. This we consider as transformational in the area of training and service delivery The Board expresses its gratitude to all who have contributed to this document, and this include the members of Medical Education and training committee, Panel of Evaluators of Internship Training, Secretariat and all those who have worked tirelessly in the revision of this Handbook. -

SDC 1. Supplementary Notes to Methods Settings Groote Schuur

Mouton JP, Njuguna C, Kramer N, Stewart A, Mehta U, Blockman M, et al. Adverse drug reactions causing admission to medical wards: a cross-sectional survey at four hospitals in South Africa. Supplemental Digital Content SDC 1. Supplementary notes to Methods Settings Groote Schuur Hospital is a 975-bed urban academic hospital situated in Cape Town, in the Western Cape province, which provides secondary and tertiary level care, serves as a referral centre for approximately half of the province’s population (2011 population: 5.8 million)1 and is associated with the University of Cape Town. At this hospital we surveyed the general medical wards during May and June 2013. We did not survey the sub-speciality wards (dermatology, neurology, cardiology, respiratory medicine and nephrology), the oncology wards, or the high care / intensive care units. Restricting the survey to general medical wards was done partly due to resource limitations but also to allow the patients at this site to be reasonably comparable to those at other sites, which did not have sub-specialist wards. In 2009, the crude inpatient mortality in the medical wards of Groote Schuur Hospital was shown to be 573/3465 patients (17%)2 and the 12-month post-discharge mortality to be 145/415 (35%).3 Edendale Hospital is a 900-bed peri-urban regional teaching hospital situated near Pietermaritzburg, in the KwaZulu-Natal province (2011 population: 10.3 million).1 It provides care to the peri-urban community and serves as a referral centre for several district hospitals in the surrounding rural area. It is located at the epicentre of the HIV, tuberculosis and multidrug resistant tuberculosis epidemics in South Africa: a post-mortem study in 2008-2009 found that 94% of decedents in the medical wards of Edendale Hospital were HIV-seropositive, 50% had culture-positive tuberculosis at the time of death and 17% of these cultures were resistant to isoniazid and rifampicin.4 At Edendale Hospital, we surveyed the medical wards over 30 days during July and August of 2013. -

Cancer Incidence in Selected Municipalities of the Eastern Cape Province, 2003–2007

Eastern Cape Province Cancer Registry Technical Report Cancer incidence in selected municipalities of the Eastern Cape Province, 2003–2007 August 2013 Authors: Ntuthu IM Somdyala, Debbie Bradshaw and Wentzel CA Gelderblom External Review: Dr Max Parkin – Co-ordinator African Cancer Registry Network (AFCRN) MS NTUTHU SOMDYALA (REGISTRY HEAD) BURDEN OF DISEASE RESEARCH UNIT SOUTH AFRICAN MEDICAL RESEARCH COUNCIL P.O BOX 19070, TYGERBERG 7505 TEL: 021- 938 0314 FAX: 021-938 0310 E-MAIL: [email protected] URL: http://www.mrc.ac.za/bod.html\ Copyright Copyright 2013 South African Medical Research Council. All materials in this report may be reproduced and copied; citation as to source, however, is appreciated. ISBN: 978-1-920618-10-0 Report Suggested citation Somdyala NIM, Bradshaw D, Gelderblom WCA. Cancer incidence in selected municipalities of the Eastern Cape Province, 2003–2007. Eastern Cape Province Cancer Registry Technical Report. Cape Town: South African Medical Research Council, 2013. ISBN: 978-1-920618-10-0. Cover Designed by Dermot Petersen i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Eastern Cape Province Non-communicable Disease Directorate is thanked for ongoing support as well as the medical superintendents, doctors and nursing personnel at the collaborating hospitals. The Registry is dependent on their routine records and their cooperation during hospital visits, which is much appreciated. The following hospitals are collaborating with the Registry: HOSPITALS IN REGISTRATION AREA North-Eastern Region Bizana St Patrick’s & Greenville Hospitals -

Sentinel Hospital Surveillance Week 23

COVID-19 SENTINEL HOSPITAL SURVEILLANCE UPDATE SOUTH AFRICA WEEK 23 2020 OVERVIEW This report summarises data of COVID-19 cases admitted to sentinel hospital surveillance sites in all provinces. The report is based on data collected from 5 March to 7 June 2020. HIGHLIGHTS ∙ As of 7 June, 6 353 COVID-19 admissions were ∙ Of the 6 353 admissions, 1974 (31%) patients reported from 242 facilities (64 public-sector were in hospital at the time of this report, and 178 private-sector) in all nine provinces 3525 (56%) patients were discharged alive of South Africa. There was an increase of or transferred out and 854 (13%) patients 1635 new admissions since the last report, had died. There were 246 additional deaths and 24 additional hospitals (7 public-sector since the last report. and 17 private-sector) reporting COVID-19 ∙ On multivariable analysis, factors admissions. There were 2990 (47%) and3363 associated with in-hospital mortality were (53%) admissions reported in private and older age groups, 40-64 years (438/3105, public sector respectively. The majority of case fatality ratio 14%; aOR 3.5; 95% CI 2.6- COVID-19 admissions were reported from 4.9) and ≥65 years (353/1234, 29%; aOR 7.2; four provinces, 4 246 (67%) in Western Cape, 95% CI 5.1-10.1) as compared to <40 years 719 (11%) in Gauteng, 547 (9%) in Eastern Cape (61/1952, 3%); male sex (439/2 927, 15%; aOR and 492 (8%) in KwaZulu-Natal. 1.5; 95% CI 1.3-1.8); admitted in the public ∙ The median age of COVID-19 admissions sector (584/3 363, 17%; aOR 1.7; 95% CI 1.4- was 49 years; 250 (4%) admissions in patients 2.1); and having comorbid hypertension <20 years and 821 (13%) in >70 years. -

Eastern Cape Healthcare Workers Acquisition of SARS-Cov-2 (ECHAS): Cross-Sectional (Nested Cohort) Study Protocol

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Protocol Eastern Cape Healthcare Workers Acquisition of SARS-CoV-2 (ECHAS): Cross-Sectional (Nested Cohort) Study Protocol Oladele Vincent Adeniyi 1,2,* , David Stead 2,3, Mandisa Singata-Madliki 4,5, Joanne Batting 4,5, Leo Hyera 6, Eloise Jelliman 7, Shareef Abrahams 8 and Andrew Parrish 2,3 1 Department of Family Medicine, Cecilia Makiwane Hospital, East London 5219, South Africa 2 Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha 5117, South Africa; [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (A.P.) 3 Department of Internal Medicine, Cecilia Makiwane and Frere Hospitals, East London 5219, South Africa 4 Effective Care Research Unit, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Frere Hospital, East London 5247, South Africa; [email protected] (M.S.-M.); [email protected] (J.B.) 5 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Fort Hare, East London 5200, South Africa 6 Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Cecilia Makiwane Hospital, East London 5219, South Africa; [email protected] 7 Department of Radiology, Frere Hospital, East London 5247, South Africa; [email protected] 8 Department of Pathology, Division of Medical Microbiology, National Health Laboratory Service, Port Elizabeth 6020, South Africa; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at increased risk of infection by the virulent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Though data exist on the positivity rate of the SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test as well as COVID-19- related deaths amongst HCWs in South Africa, the overall infection rate remains underestimated by these indicators. -

Dr Moodley CV

SEAN MOODLEY MBChB (UCT), FCS (SA), MMed Plast Surg (UCT) CURRICULUM VITAE January 2020 PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGEON TCSI 183 Bree Street Cape Town 8001 TEL :021 205 1117 E-mail: [email protected] Nationality: South African HPCSA number: MP 0562173 Pr No. : 036 000 0564753 DR SEAN MOODLEY PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGEON MBChB(UCT), FCS(SA), MMed Plast Surg(UCT) Curriculum Vitae January 2020 There are many routes to becoming a plastic surgeon, and Dr. Sean Moodley has undertaken the most thorough and demanding training process: qualifying in both general surgery and plastic and reconstructive surgery. CURRENT EMPLOYMENT Private practice at The Cosmetic Surgery Institute, CURRENT Bree street, Cape Town and at UCT private hospital. JAN 15 - PRESENT Plastic Surgeon in private practice. JAN 15 - PRESENT Groote Schuur Hospital, (PART TIME) Plastic Surgery Consultant. PREVIOUS EMPLOYMENT MAR 14 - DEC 15 Full time Plastic Surgery Consultant, Groote Schuur Hospital. FEB 09 - MAR 14 Plastic Surgery Registrar, Groote Schuur Hospital. General Surgery Junior Consultant, FEB 08 - FEB 09 New Somerset Hospital. General Surgery Registrar, SEPT 03 - FEB 08 Groote Schuur Hospital. General Surgery Medical Officer, JUL 02 - SEPT 03 Frere Hospital. ENT Medical Officer, JAN 02 - JUN 02 Frere Hospital. JAN 01 - DEC 01 General Surgery Medical Officer, Frere Hospital. JUL 00 - DEC 00 Community Service Medical Officer, Frere Hospital General Surgery and Casualty. JAN 00 - JUN 00 Community Service Medical Officer, Greys Hospital Outpatients, Casualty, Minor surgery. -

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for the Purposes

STAATSKOERANT, 16 OKTOBER 2013 No. 36936 39 No. 791 16 October 2013 HEALTH PROFESSIONS ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 56 OF 1974) LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS IN THE YEAR 2014 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 5.1 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Community Service by Persons Registering in terms of the Health Professions Act, 1974 (Act No. 56 of 1974), listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of medicine. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital* Madzikane kaZulu Hospital ** Umzimvubu Cluster Mt Ayliff Hospital** Taylor Bequest Hospital* (Matatiele) Amathole Bhisho CHH Cathcart Hospital * Amahlathi/Buffalo City Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cluster Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day Hospital Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Grey TB Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital * Komga Hospital Nkqubela TB Hospital Nompumelelo Hospital* SS Gida Hospital* Stutterheim FPA Hospital* Mnquma Sub-District Butterworth Hospital* Nqgamakwe CHC* Nkonkobe Sub-District Adelaide FPA Hospital Tower Hospital* Victoria Hospital * Mbashe /KSD District Elliotdale CHC* Idutywa CHC* Madwaleni Hospital* Chris Hani All Saints Hospital** Engcobo/IntsikaYethu Cofimvaba Hospital** Martjie Venter FPA Hospital This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za 40 No. 36936 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 OCTOBER 2013 Sub-District Mjanyana Hospital * InxubaYethembaSub-Cradock Hospital** Wilhelm Stahl Hospital** District Inkwanca -

Ptc Eastern Cape Course Report

PTC EASTERN CAPE COURSE REPORT By Dr. R. JAYAKRISHNAN CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER DEPARTMENT OF SURGERY NELSON MANDELA ACADEMIC HOSPITAL MTHATHA, EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE INTRODUCTION Following a very successful foundation course held early in 2007, PTC Eastern Cape conducted the first course in South Africa. The course was run with ample support from the provincial department of health of Eastern Cape and Walter Sisulu University. The Departments of Surgery, Anaesthesia and Family Medicine of Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital participated by contributing their staff that was trained on the earlier occasion as trainers. BACKGROUND Trauma is one of the commonest pathologies encountered in South Africa and the Province of eastern cape is no exception. All medical personals are expected to have a sound understanding of managing trauma patients. It was noticed that the standard of care offered to trauma patients was not up to standards expected resulting in significant mortality and morbidity, which is to a large extent avoidable. Prof Adekunle from the Department of Surgery discussed with Dr KLN Mafanya, the Head of the Clinical Governance of Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital Complex about offering PTC course to professionals in the peripheral hospitals thereby empowering them with the knowledge to manage trauma patients. The department fully supported the idea and it was decided to conduct the first PTC course on the 5 th and 6 th of November to be followed by further courses in the future PTC COURSE The venue of the course was Walter Sisulu University in Mthatha. Prof. E L Mazwai, the Dean for the Faculty of Health Sciences opened the programme. -

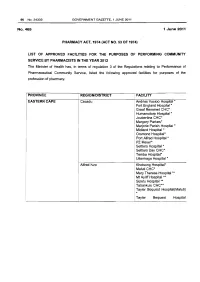

Health Professions Act: List of Approved Facilities for Community Service by Pharmacists in 2012

96 No.34332 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 1 JUNE 2011 No.465 1 June 2011 PHARMACY ACT, 1974 (ACT NO. 53 OF 1974} LIST OF APPROVED FACILITIES FOR THE PURPOSES OF PERFORMING COMMUNITY SERVICE BY PHARMACISTS IN THE YEAR 2012 The Minister of Health has, in terms of regulation 3 of the Regulations relating to Performance of Pharmaceutical Community Service, listed the following approved facilities for purposes of the profession of pharmacy. PROVINCE REGION/DISTRICT FACILITY EASTERN CAPE Cacadu Andries Vosloo Hospital * Fort England Hospital* Graaf Reneinet CHC* Humansdorp Hospital * Joubertina CHC* Margery Parkes* Marjorie Parish Hospital* Midland Hospital * Orsmond Hospital* Port Alfred Hospital * PZ Meyer* Settlers Hospital * Settlers Day CHC* Temba Hospital• Uitenhage Hospital * Alfred Nzo Khotsong Hospital• Maluti CHC* Mary Theresa Hospital .... ! Mt Ayliff Hospital ** · Sipetu Hospital •• Tabankulu CHC*• Tayler Bequest Hospitai(Maluti) * Tayler Bequest Hospital STAATSKOERANT, 1 JUNIE 2011 No. 34332 97 (Matatiele )"' Chris Hani All Saints Hospital ..... Cala Hospital ** Cofimvaba Hospital ** Cradock Hospital ** Elliot Hospital ... Frontier Hospital * Glen Grey Hospital * Mjanyana Hospital ** NgcoboCHC* Ngonyama CHC* Nomzamo CHC* Sada CHC* Thornhill CHC* Wilhelm Stahl Hospital ..... ZwelakheDalasile CHC* Nelson Mandala Dora Nginza Hospital Elizabeth Donkin Hospital Jose Pearson Santa Hospital Kwazakhele Day Clinic Laetitia Bam CH C Livingstone Hospital Motherwell CHC New Brighton CHC PE Pharmaceutical Depot PE Provincial Hospital Amathole Bedford Hospital Bhisho Hospital Butterworth Hospital Cecilia Makiwane Hospital Cathcart Hospital Dimbaza CHC Duncan Village Day CHC Dutywa CHC Empilweni Gompo CHC Fort Beauford Hospital Fort Grey Hospital Frere Hospital Grey Hospital Middledrift CHC Nontyatyambo CHC Nompomelelo Hospital Ngqamakwe CHC SS Gida Hospita Tafalofefe Hospital Tower Hospital Victoria Hospital Winterberg Hospital Willowvale CHC 98 No.