Urdu Press: an Interpretation in the Progress of Muslim Public Opinion 1920-1947

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009)

PRESS COUNCIL OF INDIA Annual Report (April 1, 2008 - March 31, 2009) New Delhi 151 Printed at : Bengal Offset Works, 335, Khajoor Road, Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110 005 Press Council of India Soochna Bhawan, 8, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Chairman: Mr. Justice G. N. Ray Editors of Indian Languages Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) NAME ORGANIZATION NOMINATED BY NEWSPAPER Shri Vishnu Nagar Editors Guild of India, All India Nai Duniya, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Uttam Chandra Sharma All India Newspaper Editors’ Muzaffarnagar Conference, Editors Guild of India, Bulletin, Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Uttar Pradesh Shri Vijay Kumar Chopra All India Newspaper Editors’ Filmi Duniya, Conference, Editors Guild of India, Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Shri Sheetla Singh Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Janmorcha, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Ms. Suman Gupta Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan, Saryu Tat Se, All India Newspaper Editors’ Uttar Pradesh Conference, Editors Guild of India Editors of English Newspapers (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri Yogesh Chandra Halan Editors Guild of India, All India Asian Defence News, Newspaper Editors’ Conference, New Delhi Hindi Samachar Patra Sammelan Working Journalists other than Editors (Clause (A) of Sub-Section (3) of Section 5) Shri K. Sreenivas Reddy Indian Journalists Union, Working Visalaandhra, News Cameramen’s Association, Andhra Pradesh Press Association Shri Mihir Gangopadhyay Indian Journalists Union, Press Freelancer, (Ganguly) Association, Working News Bartaman, Cameramen’s Association West Bengal Shri M.K. Ajith Kumar Press Association, Working News Mathrubhumi, Cameramen’s Association, New Delhi Indian Journalists Union Shri Joginder Chawla Working News Cameramen’s Freelancer Association, Press Association, Indian Journalists Union Shri G. -

Annualrepeng II.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT – 2007-2008 For about six decades the Directorate of Advertising and on key national sectors. Visual Publicity (DAVP) has been the primary multi-media advertising agency for the Govt. of India. It caters to the Important Activities communication needs of almost all Central ministries/ During the year, the important activities of DAVP departments and autonomous bodies and provides them included:- a single window cost effective service. It informs and educates the people, both rural and urban, about the (i) Announcement of New Advertisement Policy for nd Government’s policies and programmes and motivates print media effective from 2 October, 2007. them to participate in development activities, through the (ii) Designing and running a unique mobile train medium of advertising in press, electronic media, exhibition called ‘Azadi Express’, displaying 150 exhibitions and outdoor publicity tools. years of India’s history – from the first war of Independence in 1857 to present. DAVP reaches out to the people through different means of communication such as press advertisements, print (iii) Multi-media publicity campaign on Bharat Nirman. material, audio-visual programmes, outdoor publicity and (iv) A special table calendar to pay tribute to the exhibitions. Some of the major thrust areas of DAVP’s freedom fighters on the occasion of 150 years of advertising and publicity are national integration and India’s first war of Independence. communal harmony, rural development programmes, (v) Multimedia publicity campaign on Minority Rights health and family welfare, AIDS awareness, empowerment & special programme on Minority Development. of women, upliftment of girl child, consumer awareness, literacy, employment generation, income tax, defence, DAVP continued to digitalize its operations. -

The Impact of Lexical Diversity Upon Message Effectiveness in Urdu News Media: a Psycholinguistic Assessment

THE IMPACT OF LEXICAL DIVERSITY UPON MESSAGE EFFECTIVENESS IN URDU NEWS MEDIA: A PSYCHOLINGUISTIC ASSESSMENT ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of $I)iIos(Qptip IN LINGUISTICS BY AEJAZ M0HAMS4ED SHEIKH Under the Supervision of Dr. A. R. FATIHI (READER) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1998 \ 8 DEC J999 Abstract Abstract __^ Presumably, as a consequence of the apparent force and wide use of the mass media in information campaign, there has been concern for sometime with the role of communication media in the creation of message effects. The proposed research topic intends to examine the effect of lexical diversity upon message effectiveness. The study will examine the effect that messages have when communicated through a set of lexical items to produce a wholesale change in community's social construction of reality. The effect of lexical diversity upon the message will be measured by analysing the lexical choice of Urdu dailies like Qaumi Awaz. Pratap, Hind Samachar, Srinagar Times and the like. Besides, the lexical choice of All India Radio, Doordarshan, Radio Pakistan and B.B.C. will also be taken into consideration. Research about structural relations and meaning relations among the messages that form discursive constructions thus apply to the study of message effect. The study will make it clear that to take strategic decisions about the content, style and medium of messages, produced to achieve certain effects, communicators need to know not only respondents' cognitions and dispositions but also about key constituents and their interconnections in the disocourse context. In this backdrop, the present study assesses the impact of lexical diversity upon message effectiveness. -

List of Daily Newspapers Approved on 08.09.88 for Publication of Court Notices in Delhi

List of Daily Newspapers Approved on 08.09.88 For Publication of Court Notices in Delhi Sl Name of the Place/State of Publication Language Address No Newspaper 1 Hindustan New Delhi (U.T.) English 18/20, Kasturba Gandhi Marg, New Delhi. 2 Indian New -do- Express Building, Express Delhi/Madras/Chandigar Bahadur Shah Zafar, h/Hyderabad New Delhi. 3 Patriot New -do- Link House, Bahadur Delhi/Madras/Chandigar Shah Zafar Marg, h/Ahmedabad/Hyderaba New Delhi. d 4 Statesman New Delhi/West Bengal -do- Statesman House, Cannaught Cicus, New Delhi 5 Times of India Calcutta/New -do- 7, Bahadurshah Delhi/Maharashtra Zafar Marg, New Delhi 6 National U.P./New Delhi -do- 5-A, Bahadurshah Herald Zafar Marg, New Delhi 7 Assam Gauhati(Assam) -do- 3rd Floor, Room Tribune No.14, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 8 Indian Nation Bihar -do- 2rd Floor, Room No.8, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 9 The Hindu Madras (Tamil Nadu) -do- 1st Floor, Room No.5, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 10 The Tribune Chandigarh (U.T.) -do- Cannaught Place, New Delhi. 11 Deccan Herald Mysore (Karnataka) -do- 2rd Floor, Room No.5, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 12 Northern U.P. -do- 2rd Floor, Room Indian Patrika No.10, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 13 Amrit Bazar West Bengal -do- -do- Patrika 14 Anand Bazar Calcutta (West Bengal) -do- 1st Floor, Room Patrika No.7, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 15 Daily Andaman & Nicobar -do- - Telegrams Islands 16 New Hindi Goa Daman & Diu English 26, P.T.I. -

Government Advertising As an Indicator of Media Bias in India

Sciences Po Paris Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India by Prateek Sibal A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master in Public Policy under the guidance of Prof. Julia Cage Department of Economics May 2018 Declaration of Authorship I, Prateek Sibal, declare that this thesis titled, 'Government Advertising as an Indicator of Media Bias in India' and the work presented in it are my own. I confirm that: This work was done wholly or mainly while in candidature for Masters in Public Policy at Sciences Po, Paris. Where I have consulted the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. Where I have quoted from the work of others, the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations, this thesis is entirely my own work. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. Signed: Date: iii Abstract by Prateek Sibal School of Public Affairs Sciences Po Paris Freedom of the press is inextricably linked to the economics of news media busi- ness. Many media organizations rely on advertisements as their main source of revenue, making them vulnerable to interference from advertisers. In India, the Government is a major advertiser in newspapers. Interviews with journalists sug- gest that governments in India actively interfere in working of the press, through both economic blackmail and misuse of regulation. However, it is difficult to gauge the media bias that results due to government pressure. This paper determines a newspaper's bias based on the change in advertising spend share per newspa- per before and after 2014 general election. -

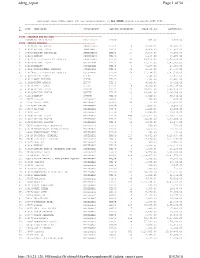

Newspaper Wise Committment for All Advertisements in All State During the Period 2005-2006

advtg_report Page 1 of 54 NEWSPAPER WISE COMMITTMENT FOR ALL ADVERTISEMENTS IN ALL STATE DURING THE PERIOD 2005-2006. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SL CODE NEWSPAPER PUBLICATION LAN/PER INSERTIONS SPACE(SQ.CM) AMOUNT(RS) NO ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STATE : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR------------------------------------------------------ 1. 400068 ANDAMAN MURASU PORT BLAIR TAM/W 4 975.00 4,729.00 STATE : ANDHRA PRADESH------------------------------------------------------ 1. 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 18 10,630.00 52,301.00 2. 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 33 19,918.00 1,31,867.00 3. 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENG/D 27 9,050.00 54,064.00 4. 410251 EENADU ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 7 6,258.00 73,084.00 5. 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 60 29,516.00 1,78,919.00 6. 410219 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPPAH TEL/D 41 25,132.00 1,45,606.00 7. 410260 EENADU CUDDAPPAH TEL/D 5 3,209.00 27,985.00 8. 410227 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TEL/D 12 8,451.00 67,417.00 9. 410158 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TEL/D 68 31,198.00 1,81,714.00 10. 410012 ELURU TIMES ELURU TEL/D 7 3,540.00 27,852.00 11. 410117 GOPI KRISHNA ELURU TEL/D 7 2,795.00 32,807.00 12. 410009 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TEL/D 14 8,010.00 75,620.00 13. 410114 STATE TIMES ELURU TEL/D 19 9,630.00 1,00,487.00 14. 410194 ANDHRA JYOTHI GUNTUR TEL/D 72 38,031.00 2,90,858.00 15. -

The Earlier Papers Dealt with the Muslim League Within the Cont

C. M. Naim THE MUSLIM LEAGUE IN BARABANKI, 1946:* A Sentimental Essay in Three Scenes No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be; Am an attendant lord, one that will do To swell a progress, start a scene or two…. (T. S. Eliot, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”) Or, as in the case here, Merely three Scene 1 In December 1906, twenty-eight men traveled to Dhaka to represent U.P. at the formation of the All India Muslim League. Two were from Bara Banki, one of them my granduncle, Raja Naushad Ali Khan of Mailaraigunj. Thirty-nine years later, during the winter of 1945-46, I could be seen marching up and down the only main road of Bara Banki with other kids, waving a Muslim League flag and shouting slogans. No, I don’t imply some unbroken trajectory from my granduncle’s trip to my strutting in the street, for the elections in 1945 were in fact based on principles that my granduncle reportedly opposed. It was Uncle Fareed who first informed me that Naushad Ali Khan had gone to Dhaka. Uncle Fareed knew the family lore, and enjoyed sharing it with us boys. In an aunt’s house I came across a fading picture. Seated in a dogcart and dressed in Western clothes and a * Expanded version of a paper read at the conference on “The 100 Years of the Muslim League,” at the University of Chicago, November 4, 2006. 1 PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com jaunty hat, he looked like a slightly rotund and mustached English squire. -

Title Dr. Mohammad Kazim Educational

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site (PLEASE FILL THIS IN AND Email it to [email protected] and cc: [email protected] Title Dr. Mohammad First Last Name Photograph Kazim Name Designation Associate Professor Address 38/22 Probyn Road University of Delhi Delhi – 110007 Phone No Office 011- 27666627 Residence 011- 27662051 Mobile 0-9868188463, 09818543226 Email [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. Jawaharlal Nehru University 2001 M.Phil. Jawaharlal Nehru University 1996 PG Jawaharlal Nehru University 1994 UG University of Calcutta 1992 ADOP Mass Media Jawaharlal Nehru University 1995 Career Profile Associate Professor, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, since 2011 Sr. Assistant Professor, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, 2007 - 2011 Lecturer/Assistant Professor, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, joined in 2002 Worked as Sub – Editor (Ajkal Urdu), Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India, from 1998 to 2002 Administrative Assignments Worked as Deputy Proctor, University of Delhi since January 2011 to 2017 Worked as Resident Tutor, Mansarowar Hostel, University of Delhi, from 2006 to 2010 Worked as Resident Tutor (Officiating), Gwyer Hall, University of Delhi, from May 2010 to July 2010 Member, Board of Studies, Chaudhry Charan Singh University, Meerut. Since 2009 Member, Arts Faculty, University of Delhi, Delhi, since 2009 Secretary, Departmental Council, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, since 2009 Teacher In-charge, Bazm-e-Adab, a literary and Cultural organization of Students, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi – 110 007, 2009 - 2011 Honorary General Secretary, Bahroop Arts Group (Regd.) New Delhi since 2008 In-charge, P G Diploma in Mass Media, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi – 110 007 Member, Board of Research Studies of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Delhi, 2003 – 2005. -

National Herald Case

National Herald Case Why in news? The Delhi High Court recently dismissed pleas by Congress leaders against the Income Tax department’s decision to reopen their tax assessments for the year 2011-12. National Herald Newspaper It was established by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1938. It was published by The Associated Journals Limited, a “Section 25” company, which is generally a not-for-profit entity. AJL also published the Qaumi Awaz in Urdu and Navjeevan in Hindi. The company owns prime real estate in various cities, including Delhi and Mumbai worth around Rs.2000 Cr. Veteran Congress leader Motilal Vora has been the chairman and managing director of AJL since March 22, 2002. What is the case about? The IT department’s decision is related to the National Herald newspaper case. In 2012 a complaint was filed by BJP leader Subramanian Swamy before the trial court. It was alleged that Congress leaders were involved in cheating and breach of trust in the acquisition of Associated Journals Ltd (AJL) by Young Indian Pvt Ltd (YIL), as assets worth crores of rupees had been transferred to YIL. Congress president Sonia Gandhi and vice president Rahul Gandhi are its board of director. Congress treasurer Motilal Vora and general secretary Oscar Fernandes were also named in the case. What happened? AJL ran into losses by overstaffing and a lack of revenue and stopped publishing in April 2008. The Congress party gave the company unsecured, interest-free loans for a few years up to 2010 to keep it afloat. On 2010, a new company called Young Indian Pvt Ltd (YIL) was incorporated as a Section 25 company. -

LIST of DAILY NEWSPAPERS APPROVED on 08.09.88 for PUBLICATION of COURT NOTICES in DELHI (With Further Updating Upto February, 2015)

LIST OF DAILY NEWSPAPERS APPROVED ON 08.09.88 FOR PUBLICATION OF COURT NOTICES IN DELHI (with further updating upto February, 2015) Sl. Name of the Place/State of Language Address No. Newspaper Publication 1. The Hindustan Times New Delhi (U.T.) English 18/20, Kasturba Gandhi Marg, New Delhi. 2. Indian Express New Delhi / -do- Express Building, Bahadur Madras / Shah Zafar, New Delhi. Chandigarh / Hyderabad 3. Patriot New Delhi / -do- Link House, Bahadur Shah Madras / Zafar Marg, New Delhi. Chandigarh / Ahmedabad / Hyderabad 4. The Statesman New Delhi / West -do- Statesman House, Bengal Cannaught Cicus, New Delhi 5. The Times of India Calcutta / New -do- 7, Bahadurshah Zafar Delhi / Marg, New Delhi Maharashtra 6. National Herald U.P./New Delhi -do- 5-A, Bahadurshah Zafar Marg, New Delhi 7. Assam Tribune Gauhati(Assam) -do- 3rd Floor, Room No.14, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 8. Indian Nation Bihar -do- 2rd Floor, Room No.8, I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 9. The Hindu Madras (Tamil -do- 1st Floor, Room No.5, Nadu) I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 10. The Tribune Chandigarh (U.T.) -do- Cannaught Place, New Delhi. 11. Deccan Herald Mysore -do- 2rd Floor, Room No.5, (Karnataka) I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 12. Northern Indian U.P. -do- 2rd Floor, Room No.10, Patrika I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 13. Amrit Bazar Patrika West Bengal -do- -do- 14. Anand Bazar Patrika Calcutta (West -do- 1st Floor, Room No.7, Bengal) I.N.S.Building, Rafi Marg, New Delhi 15. -

Title Dr. Mohammad Kazim Educational

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Dr. Mohammad First Last Name Photograph Name Kazim Designation Associate Professor Address 38/22 Probyn Road University of Delhi Delhi – 110007 Phone No Office 011- 27666627 Residence 011- 27662051 Mobile 0-9868188463, 09818543226 Email [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. Jawaharlal Nehru University 2001 M.Phil. Jawaharlal Nehru University 1996 PG Jawaharlal Nehru University 1994 UG University of Calcutta 1992 ADOP Mass Media Jawaharlal Nehru University 1995 Career Profile Associate Professor, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, since 2011 Sr. Assistant Professor, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, 2007 - 2011 Lecturer/Assistant Professor, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, joined in 2002 Worked as Sub – Editor (Ajkal Urdu), Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India, from 1998 to 2002 Administrative Assignments Working as Deputy Proctor, University of Delhi since January 2011 Worked as Resident Tutor, Mansarowar Hostel, University of Delhi, from 2006 to 2010 Worked as Resident Tutor (Officiating), Gwyer Hall, University of Delhi, from May 2010 to July 2010 Member, Board of Studies, Chaudhry Charan Singh University, Meerut. Since 2009 Member, Arts Faculty, University of Delhi, Delhi, since 2009 www.du.ac.in Page 1 Secretary, Departmental Council, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi, since 2009 Teacher In-charge, Bazm-e-Adab, a literary and Cultural organization of Students, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi – 110 007, 2009 - 2011 Honorary General Secretary, Bahroop Arts Group (Regd.) New Delhi since 2008 In-charge, P G Diploma in Mass Media, Department of Urdu, University of Delhi, Delhi – 110 007 Member, Board of Research Studies of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Delhi, 2003 – 2005. -

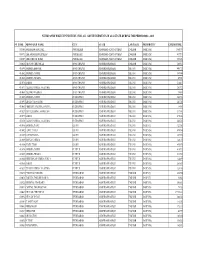

Newspaper Wise Expenditure for All Advertisements in All State During the Period 2010 - 2011

NEWSPAPER WISE EXPENDITURE FOR ALL ADVERTISEMENTS IN ALL STATE DURING THE PERIOD 2010 - 2011 NP_CODE NEWSPAPER_NAME CITY STATE LANGUAGE PERIODICITY EXPENDITURE 101064 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1466949 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORTBLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 455597 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORTBLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 533126 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH ENGLISH DAILY(M) 288765 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 440773 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 389840 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 45101 410370 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 314487 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 203573 410400 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 76969 410219 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPPAH ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 366316 410391 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 243745 410403 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 14103 410227 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 317141 410377 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 278948 410158 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 264738 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(E) 123326 410012 ELURU TIMES ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 699694 410117 GOPI KRISHNA ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH TELUGU DAILY(M) 287353 410009 RATNA GARBHA ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH