The Story of Lillian Trasher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Women's 400M Hurdles Championship

College Women's 400m Hurdles Championship EVENT 101THURSDAY 10:00 AM FINAL ON TIME PL ID ATHLETE SCHOOL/AFFILIATION MARK SEC 1 2 Samantha Elliott Johnson C. Smith 57.64 2 2 6 Zalika Dixon Indiana Tech 58.34 2 3 3 Evonne Britton Penn State 58.56 2 4 5 Jessica Gelibert Coastal Carolina 58.84 2 5 19 Faith Dismuke Villanova 59.31 4 6 34 Monica Todd Howard 59.33 6 7 18 Evann Thompson Pittsburgh 59.42 4 8 12 Leah Nugent Virginia Tech 59.61 3 9 11 Iris Campbell Western Michigan 59.80 3 10 4 Rushell Clayton UWI Mona 59.99 2 11 7 Kiah Seymour Penn State 1:00.08 2 12 8 Shana-Gaye Tracey LSU 1:00.09 2 13 14 Deyna Roberson San Diego State 1:00.32 3 14 72 Sade Mariah Greenidge Houston 1:00.37 1 15 26 Shelley Black Penn State 1:00.44 5 16 15 Megan Krumpoch Dartmouth 1:00.49 3 17 10 Danielle Aromashodu Florida Atlantic 1:00.68 3 18 33 Tyler Brockington South Carolina 1:00.75 6 19 21 Ryan Woolley Cornell 1:01.14 4 20 29 Jade Wilson Temple 1:01.15 5 21 25 Dannah Hayward St. Joseph's 1:01.25 5 22 32 Alicia Terry Virginia State 1:01.35 5 23 71 Shiara Robinson Kentucky 1:01.39 1 24 23 Heather Gearity Montclair State 1:01.47 4 25 20 Amber Allen South Carolina 1:01.48 4 26 47 Natalie Ryan Pittsburgh 1:01.53 7 27 30 Brittany Covington Mississippi State 1:01.54 5 28 16 Jaivairia Bacote St. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2011 No. 21 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was The Lillian Trasher Orphanage, loudest voice on the field because called to order by the Speaker pro tem- begun in 1911 by an American from that’s the kind of person that she is. pore (Mr. CHAFFETZ). Jacksonville, Florida, is one of the old- She is passionate, she is fierce in her f est and longest-serving charities in the dedication to her friends, and she has world. It currently serves over 600 chil- devoted her entire life to making her DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO dren, along with widows and staff. This community, her State, and her country TEMPORE pillar of the community has been home a better place for all Americans. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- to thousands of children who needed Bev recently had a curveball thrown fore the House the following commu- food, shelter, and a family. Orphanage at her when she was diagnosed with nication from the Speaker: graduates serve around the world as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also WASHINGTON, DC, bankers, doctors, pastors, teachers, and known as ALS—Lou Gehrig’s Disease. February 10, 2011. even in the U.S. Government. Bev has always taken life head-on, and I hereby appoint the Honorable JASON Despite many challenges over the that’s how she addressed this chal- CHAFFETZ to act as Speaker pro tempore on years, the wonderful staff, now led by lenge, the same way she has lived her this day. -

“Making Full Proof of Their Ministry”: Women in Church of God Missions

“Making Full Proof of Their Ministry”: Women in Church of God Missions Wanda Thompson LeRoy and David G. Roebuck* The First Missionary In November 1909 Rebecca Barr and her husband Edmond sailed from Miami to take the gospel to the British colony of the Bahama Islands. When they landed in Nassau, Rebecca Barr became the first Church of God missionary.1 Although many of the details of their lives and ministries have been lost to time, the Barr‘s story is an important chapter in Pentecostal missions. Born in in 1865, Rebecca Clayton married Edmond Barr at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Arcadia, Florida, in 1894. A native of the Bahamas, Edmond had likely come to the United States to find work. In May 1909 the couple attended a South Florida Holiness Association camp meeting on the Pleasant Grove Campground in Durant, Florida. There they received the baptism of the Holy Spirit, joined the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee), and received ministerial credentials as evangelists.2 In October 1909 the Barrs returned to the Pleasant Grove camp meeting, where they sensed a call to take the gospel to the Bahama Islands. As was their practice, camp meeting attendees raised funds to aid the Barrs on their journey.3 Robert M. Evans, who led the camp meeting, determined to join the Barrs in the Bahamas. Evans, his wife, Ida, and the young Carl Padgett arrived in Nassau on January 4, 1910. Evans reported that his party “immediately hunted up brother and sister Barr…, who were making full proof of their ministry.”4 Together these five worked as a team to preach the gospel and establish Church of God congregations throughout the islands.5 Although secondary sources have given little attention to Rebecca Barr, published reports of the work in the Bahamas reveal that she was an active part of the ministry team. -

Children Preaching Onthe Sawdust Trail

CHILDREN PREACHING ONTHE SAWDUST TRAIL A Ilerilage Photo FC~lture on Children in the Ministry During the 1930s and 19-Ws. I-low nmny do )Oll rcI11Cml>CI"? Begins on page 3. S PIU ~G 1996 VO L. 16, NO. I PAC E 4 PAGE 18 PAG E 28 4 19':'1 C1.ASS It EU:\ ION. These member, of the 1937 cia" of Glad \RClII \ ES ST\FF-\\ \Y .... E E. \\ \K .... EK. Tiding .. B,hle IIl'.titutc gOl together 1:I\t year for their 54th anniver.'>ary. J~ I )lTO R .\ .... 1) t\lH; 1I1\ ES DlIn:CT(lK: A Texas writer tdh us abOllt their tllllC" in the 19](h and last year. By JO\CE LEE. \SSIST\ .... T \KClII\IST: Dawn Chalalre C I.E" .... GOII R.. \ RCIII\ ES ASSISTANT A.... [) COI'Y EDiTOH: C I .... DY C I{AY. $EC HETAln . CA I{L W. HAR NES. Starting to pro.:aeh the Pelllcco·,t:d Illes\agc at the ,\RC II1 VES ,\ f)VISO I{ Y n OA RD-CIl A II{· 6 MAN GEORGE O. " OOD. J . CALV I N :Ige of 4:!. n"rne~ promi .. ed he would pn.:ach the go'pelthe rest of hi, HOLS ' .... (;ER, (; \ In' 11 . ~kGE E . CII AlO,ES life. He died \\hilc preaching:!6 years laler. By Glenn Gollr CI{)\In'REF:. 11 FAITII FUL l '''iTO DEATH. After suffering a heart atWd:! ye<lr" agt). Ihi, 94·}"ear-old I·{'tired preaehcr di,t'u"e, the importance of II 1.1<'IlIillit'.1 (if G"II "{'ri/!l .~" j, puhh'h<,d ((";tncrl) remaining failhful to the Lord. -

Osmanlı Devleti'nin Ve Hakimiyeti Altında Yaşayan Halkların Batılılaş

Kitap Tanıtımı / Book Review Ayşe Aksu Mehmet Ali Doğan ve Heather J. Sharkey (ed.) American Missionaries and the Middle East: Foundational Encounters Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2011, 346s. smanlı Devleti’nin ve hakimiyeti altında yaşayan halkların Batılılaş- Oma süreçlerindeki önemli unsurlardan biri de hiç kuşkusuz Amerikan misyonerlerinin faaliyetleridir. Protestan anlayışa göre şekillenen dünya gö- rüşlerini yazılı ve sözlü olarak aktaran Protestan misyonerler Osmanlı top- raklarında siyaset, eğitim ve dil alanında etkili olmuş, günümüze kadar de- vam eden derin izler bırakmışlardır. Ülkemizde yaklaşık iki asırdır yaşanan modernleşme sürecinde Amerikalı misyonerlerin faaliyetlerini konu alan pek çok araştırma yapılmış olup halen de bu araştırmalara yenileri eklenmekte- dir. Ancak yurtdışında yapılan inceleme ve araştırmaların, yerli araştırmalara kıyasla nitelik ve nicelik bakımından genellikle daha ileri aşamalarda olduk- ları bir gerçektir. Bu çalışmalardan biri de American Missionaries and the Middle East: Foundational Encounters adlı kitaptır. Sahasının uzmanı kişile- rin kaleme aldığı dokuz makaleden oluşan bu kitapta Amerikalı misyonerlere, kurumlarına veya faaliyetlerine toptan bir bakış yerine, bu olguyu meydana getiren çeşitli bileşenlerin sondaj usulüyle incelenmesi, sebep-sonuç ilişkisi içerisinde ele alınması tercih edilmiştir. Doğal olarak bu yaklaşım tarzı konu- yu içine kapatmaktan ziyade sosyolojik gelişmelerle ve unsurlarla da harman- layarak disiplinler arası bir incelemeye açmayı öncelemiş görünmektedir. Öte yandan örneklem olarak seçilen coğrafyaların (İstanbul, Beyrut, Bulgaristan, Mısır) çeşitliliği de dikkatlerden kaçmamaktadır. Bu yönüyle de kitap Ameri- kan misyonerliğinin coğrafi olarak geniş bir alana yayıldığını, kültürlere göre söylem ve eylem değişikliklerinin olabileceğini okuyucuya hatırlatmaya özen göstermiştir. Kitap Heather J. Sharkey’nin hem kitaptaki makaleleri tanıttığı hem de Ortadoğu’daki Amerikan misyonerlik faaliyetlerinin bir özetini sunduğu gi- riş kısmıyla başlamaktadır. -

Assemblies of God 8~ R.II

Wir e" Pe"tecost Came to Habama Assemblies of God 8~ R.II . Spt!ncc ~I "6:"'. ",ri. I~ ,.,...w:,,~, , J,.. ."I R --- Rn..... ' ..." .II" ..... 11.-, •. 1911 nr...... ................;~ ~~~~.... ~~::::::~~~::~ :":' ...................\~ rn~. ':. ~':.:. :'.~\:\:',,:":'.:1~.8~ From The American Maga:il/e. June 1939 •• - ~-:....-=- They call her the greatest woman in Egypt-this big-hearted American who looks like Marie Dress- ler and is "Mamma" to 700 orphans and widows J E ROM E EAT T y gyP' ,~ a land of wondcr~. but (0 me E its grcatc~t ,~ M,~:> L,llmn Tra,hcr. hugc and hcany. once of Jad..~onvillc. Fla .. mOlhcr to (>-l7 Egyptian orphan" and 74 pcnnilc:>s widows. At A!. .... ioul, Egypt. shc conduth onc of thc mO~1 amazmg o{X!n hous.c~ in thc world No de!.crving Lillian Trashu child or .... ,dow ha!> cver been turncd al Ass;()ul. /938. l'holf) by Jerome away. IJealty The my~lery of the Sphmx , ~ a ch,ld's Con/inu, /I /UI fHJJ(t J THE HERITAGE t,ETTJ,j:R Wayn, Wom" ' H'U b.ne alre.ld) nntn.:cd, Ibl" ,,"uc A01 lIallCllW .\ la~lng d do\C h"ltlk, at an Aw.:lIlbln,', III (jnd legend and ,lnc of the l-!TC,II .... olllen of thl .. L"cnlUl) I.tlhan Tr:hhcr IIKK7·196t) \1." Tra .. hcr', orphanage ;11 A""I(lut, L:g)pt ..... hKh ... no .... L"allcd the Lllhan Tra:.hcr Memorial Orphanage, will be 7" year. old on FchruilfY 10. On that da} In 1911, I. l1h,Ul!OO!.. it lin} baby gIrl 11110 her home. -

Pioneers of Faith

Pioneers of Faith 2 Pioneers of Faith by Lester Sumrall 1 Pioneers of Faith by Lester Sumrall South Bend, Indiana www.leseapublishing.com 3 Pioneers of Faith Unless otherwise indicated, all Scripture quotations are taken from the King James Version of the Bible. Photographs in Chapters 1-10 and 12-24 are used by permission of Assemblies of God Archives, 1445 Boonville Avenue, Springfield, Missouri 65802-1894. Pioneers of Faith ISBN 1-58568-207-1 Copyright © 1995 by LeSEA Publishing 4th Printing August 2018 LeSEA Publishing 530 E. Ireland Rd. South Bend, IN 46614 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved under International Copyright Law. Contents and/or cover may not be reproduced in whole or in part in any form without the express written consent of the Publisher. 4 Dedication I dedicate this volume to the memory of Stanley Howard Frodsham (1882-1969): a man who loved people, a man who blessed people, a man who helped pioneer the move of the Holy Spirit in this century. He inspired my life from the first day we met. We were together again and again in his home, his office, and in public meetings. He was present in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, when I was twenty years old, and the Lord showed Howard Carter that I was the young man to go with him around the world. Stanley Frodsham wrote for posterity most of the chal- lenging story that the world knows about Smith Wigglesworth. For this the Church of all time will hold him in honor. I will never forget his humility and his prolific producing of spiritual material — much of which does not have his name on it. -

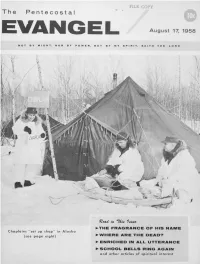

1958 08 17.Pdf

fiLE COpy The Pentecostal E GEL August 17, 1958 NO T B Y M IG H T. N OR B Y POW e: R. • U T B Y M Y 5 P I R I T . 5 A I T H THE L 0 ,. D , " ) " f / / If / • r • - I . ., "I "- , • ---- ~ J :<:<44 u. 7~ 1444e ~THE FRAGRANCE OF HIS NAME Chaplains " set up shop " in Ala s ka (see pog e e ight) ~WHERE ARE THE OEAD? ~ ENRICHED IN ALL UTTERANCE ~ SCHOOL BELLS RING AGAIN and other articles of s piritual inte rest THE EDITORIAL VIEWPOINT The Pentecostal • EVANG L Bloodshed In the Middle East WEEKLY VOICE OF THE ASSEMBLIES OF GOD AUGUST 17, 1958 NUMBER 2310 The headlines tell of a bloody revolt in Iraq, civil war in Lebanon, and a tense si tuation in other Bible lands. The news reminds us that EDITOR .. ROBERT C. CUNNINGHA~{ the Middle East is \"'here human government began and it is there EXEClITI\'E DIRECTOR . 1. R. FlOU'cr it will end when Christ returns. LAYOUT EDITOR Lrslic IV. Stili/II EDITORIII.L A~SISTA:oIT Elm Af. J olmJOII \nlilc Christians everywhere arc praying fo r peace, we know from EDITORIAL POLICY BOARD the Scriptures that there shall not be lasting peace ;J,S long as men J, R. FIo"'H (nt~irm~n) . Howard S. Ilu.h. D. 11. are !.inners. There shall be waTS alld rumors of wars until the \lci.aullhl"l. R,,~ H. \\'e~(I. A~ron A \\,it'on Prince of Peace returns to earth to take the reins of government in His own hands. -

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (Abcfm)

AMERICAN BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS FOR FOREIGN MISSIONS (ABCFM) AND “NOMINAL CHRISTIANS”: ELIAS RIGGS (1810-1901) AND AMERICAN MISSIONARY ACTIVITIES IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE by Mehmet Ali Dogan A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Middle East Studies/History Department of Languages and Literature The University of Utah May 2013 Copyright © Mehmet Ali Dogan 2013 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Mehmet Ali Dogan has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Peter Sluglett Chair 4/9/2010 Date Approved Peter von Sivers Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved Roberta Micallef Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved M. Hakan Yavuz Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved Heather Sharkey Member 4/9/2010 Date Approved and by Johanna Watzinger-Tharp Chair of the Department of Middle East Center and by Donna M. White, Interim Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In this dissertation, I investigate the missionary activities of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) in the Ottoman Empire. I am particularly interested in exploring the impact of the activities of one of the most important missionaries, Elias Riggs, on the minorities in the Ottoman Empire throughout the nineteenth century. By analyzing the significance of his missionary work and the fruits of his intellectual and linguistic ability, we can better understand the efforts of the ABCFM missionaries to seek converts to the Protestant faith in the Ottoman Empire. I focus mainly on the period that began with Riggs’ sailing from Boston to Athens in 1832 as a missionary of the ABCFM until his death in Istanbul on January 17, 1901. -

February 11, 1962 TEN CENTS

The Pen.teoosta.l February 11, 1962 TEN CENTS NOT By M ,GHT. NOR OV POWt;R. nUT OY .... Y ~" 'T, .... n." H.E ~ORO • RE~'C'OU$ NeWs THIS WEEK' S COVER Thesc 'it'rrc his it'ords---a"d his epitaph: "With malicc t07.I.'(1rd 1101IC." This statllc of a young Abraham Lincohl !lATIN(: SIN stallds at the entrallce of New Salem, Ill., the vmage in There is only olle thing to do with sin-hate it. Hate which he li1.'cd for six )'('ars. It shows tile great emanci it ill your own life. llatc it in the lives of others. pator carrying a law book and an axe: tI,C "rail-splitter" 1t is said that when the emperor of Constantinople (IIld attorncy 1.1.'110 'it'C 'lt 0 11 to greatness it! the Presidenc)'. arrested Chrysostom and thought of trying to make him recant, the great preacher slowly shook his head. The emperor said to his attendants. "Put him in prison." DIRECTION ~IAKES TilE DI FFERENCE ":-\0," said one of them, "he will be glad to go, for Holiness is very much a matter of aspect. We arc he delights in the presence of his God in quiet." changed by beholding; therefore, vcry much depends on "Well, then. let liS execute him," sa id the emperor. the way in which we look. "lie will be glad to die," said the attendant, "for Once, in the happy month of ~fay, , \.... alked with a he wanls 10 go to hC3vcn-I heard him say so the fricnd in his orchard, mar\'e1ling at the exquisite show Oilier day. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 157 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2011 No. 21 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was The Lillian Trasher Orphanage, loudest voice on the field because called to order by the Speaker pro tem- begun in 1911 by an American from that’s the kind of person that she is. pore (Mr. CHAFFETZ). Jacksonville, Florida, is one of the old- She is passionate, she is fierce in her f est and longest-serving charities in the dedication to her friends, and she has world. It currently serves over 600 chil- devoted her entire life to making her DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO dren, along with widows and staff. This community, her State, and her country TEMPORE pillar of the community has been home a better place for all Americans. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- to thousands of children who needed Bev recently had a curveball thrown fore the House the following commu- food, shelter, and a family. Orphanage at her when she was diagnosed with nication from the Speaker: graduates serve around the world as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also WASHINGTON, DC, bankers, doctors, pastors, teachers, and known as ALS—Lou Gehrig’s Disease. February 10, 2011. even in the U.S. Government. Bev has always taken life head-on, and I hereby appoint the Honorable JASON Despite many challenges over the that’s how she addressed this chal- CHAFFETZ to act as Speaker pro tempore on years, the wonderful staff, now led by lenge, the same way she has lived her this day. -

Cast of Characters

CAST OF CHARACTERS American Mission. The largest mission in Egypt, with headquarters in Cairo, hospitals in Asyut and Tanta, schools throughout the country, and an orphan- age in the capital. Started in 1854 and affiliated with the Board of Foreign Mis- sionaries of the United Presbyterian Church of North America (UPCNA). Charles Adams. Chairman of the faculty of the Theological Seminary, Cairo. Ellen Barnes. Succeeded Margaret Smith as head of the Fowler Orphanage. Egyptian Missionary Association. Group administering the affairs of the American Mission, reporting back to the Board of Foreign Missions of the UPCNA and the Women’s General Missionary Society. Evangelical Church. Autonomous Egyptian Presbyterian church started by American missionaries. Esther Fowler and John Fowler. Quaker couple who funded the girls’ orphanage in Cairo named for them. Margaret (Maggie) Smith. Moving spirit behind the founding of the Fowler Orphanage in 1906 and its first head. Samuel Zwemer. Loose affiliate of the American Mission, prolific writer, and field referee of the Swedish Salaam Mission. American Diplomats William Jardine. Minister of the Legation of the United States of America. Horace Remillard. American consul in Port Said. Assemblies of God Mission. Came to oversee Pentecostal missions in Egypt, which were initially unaffiliated with a board or church. Lillian Trasher. Pentecostal founder of the faith-based Asyut Orphanage in 1911. CAST OF CHARACTERS xix Body of Grand ‘Ulama’. Council of senior clerics at the al-Azhar mosque- university complex. Shaykh Muhammad al-Ahmadi al-Zawahiri. Rector of al-Azhar. British Officials W. J. Ablitt Bey. Commander of the Suez Canal police, special branch, Port Said.