Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project ST MARY's LONGFLEET POOLE, DORSET Ambition To

PROJECT ST MARY'S LONGFLEET POOLE, DORSET AMBITION To install a new energy efficient heating system for differing requirements that ensure a warm, inviting and safe church environment. ST MARY'S LONGFLEET POOLE, DORSET HEATING SOLUTION CONTINUOUS TEMPO LST CONSULTING ENGINEERS WORLDWISE LTD H & V CONTRACTORS DIXONS MECHANICAL SERVICES St Mary's, Longfleet, in Poole, Dorset is a Grade II listed the centre is not in continuous use but at odd hours during Church of England parish church offering an informal the day. It also had to be safe for all visitors to the centre, atmosphere of worship for, like many churches, a multi- especially the elderly and young who tend to be among the generational congregation. most frequent users. Built in the early 1830’s and consecrated in September Worldwise had prior experience of successful working with 1833, the Gothic style church has been considerably Jaga on a number of other ecclesiastical projects in the modified in the ensuing years. However, the original South Coast area - including the refurbishment of Bridport northwest tower and spire remain one of Poole's most Unified Church and St Luke’s Church in the heart of the important landmarks to this day. New Forest - so selected them again as the manufacturer that could provide the best all-encompassing radiator The most recent building works saw the redevelopment of specification and supply service. After taking the time the church centre which is a heavily used facility serving to understand the specific needs of the project, Jaga’s both the church and the entire local community. -

South West Wales North West South West Central North

Inns Rooms with character located above one of our welcoming pubs. Lodges Where to find us Purpose built accommodation with air conditioning, disabled access and all the modern essentials you would expect when staying away from home. SCOTLAND NORTH EAST 30. CHAIN RUNNER 20. THE GREEN DRAGON 22. LOBSTER POT Almondvale Way, Livingston EH54 6GA Cowgate, Welton, 184 Kingsgate,Bridlington YO15 3NG 01506 243991 East Yorkshire 01262 602834 HU15 1NB 23. OWL HOTEL 31. HARBOUR SPRING 01482 666700 Buchan Way, Peterhead AB42 3GT Main Street, Selby, YO8 9JH 01779 252252 21. KINGS CHAMBER 01757 228374 Thorne, Doncaster 24. PENNY HEDGE 32. HIGHLAND GATE DN8 4JE Stainsacre Lane, Whitby YO22 4NL Drip Road, Stirling FK9 4UA 01405 955060 01786 542090 01947 661548 Peterhead 31 33. PINE MARTEN Spott Road, Dunbar, East Lothian EH42 1LE 01368 860013 CENTRAL 34. QUEEN OF THE LOCH 1. BOUNDARY Old Luss Road, Balloch, Alexandria G83 8QW Lea Vale, 6. GROUSE & CLARET 01389 656070 Broadmeadows, Station Road, Rowsley, Derbyshire, Alfreton DE55 3NA Matlock DE4 2EB 35. RAVENS CLIFF 01629 733233 rospect Hill Road, Motherwell ML1 2UE 01773 582840 01698 313090 7. HEART OF ENGLAND 2. CREWE & HARPUR 34 32 Weedon, Daventry, Northampton NN7 4QD 36. RED SQUIRREL Swarkestone, 37 01327 340335 Ashenyards Park, Stevenston KA20 3DA Derby DE73 7JA 01294 588010 30 33 01332 700641 8. KINGS HIGHWAY 35 Rowditch, Derby DE22 3NH 36 3. THE CROWN 37. SWEET CHESTNUT Wychbold, Droitwich 01332 349671 11 Fife Leisure Park, Dunfermline KY11 8EX WR9 7PF 9. TULIP QUEEN 01383 734103 01527 861413 Barrier Bank Development, Spalding PE12 6AE 4. -

The Information Requirements of People with Cancer Where to Go After the “Patient Information Leaflet”?

© 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc., Philadelphia Claire Balmer, MSc, RGN The Information Requirements of People With Cancer Where to Go After the “Patient Information Leaflet”? KEY WORDS Information is crucial for people with cancer for both successful treatment and Cancer care rehabilitation and to facilitate user involvement and informed decision making. Internet Research has tended to concentrate on biomedical sources, such as hospital- Media produced information. There have been few inductive investigations of patients’ Naturalistic inquiry use of information available outside this environment, despite the media and Patient information Internet being identified as pervasive sources of cancer information. This article reports on a study that utilized naturalistic inquiry to explore the extent and manner in which the media and Internet are utilized as information sources by people with cancer. Results confirm that the media was used considerably by the study sample and was an important contributor to knowledge and facilitator for decision making. Participants were not passive receivers of media messages but interpreted it depending on their particular needs or their rating of the media source. Consumption of media-produced information was constrained by certain factors, such as the participants’ physical inability to access sources, and needs were not always satisfied because media discourse and “newsworthiness” restricted the reporting of what was sought. The study highlights the importance of the media and Internet as an information source for people with cancer and calls for a greater awareness of this phenomenon. uch attention is given to the information needs of access to it is vital for healthcare consumerism, user involve- people with cancer. -

HMO Register

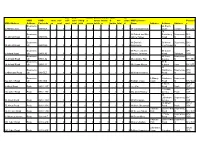

non- bedr permi permit-shared- share wc- HMO HMO store self- self- oom- living- t- house kitche d- wc- share HMO Licensee Postcod HMO Address Address Postcode ys cont cont total total occup holds n bathro total d Name Address Address Address e Bournemo 26 South 5 Abbott Close uth BH9 1EX 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 1 1 1 Mr Christopher Ely Close London N6 5UQ 18 Bournemo Mr Robert and Mrs Saxonbury Bournemou BH6 34 Abbott Road uth BH9 1HA 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 3 0 2 Janice Halsey Road th 5NB Bournemo Mr Dominik 59 Heron Bournemou BH9 40 Abbott Road uth BH9 1HA 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 2 Kaczmarek Court Road th 1DF Bournemo Mr Peter and Mrs 65 Castle SP1 5 Acland Road uth BH9 1JQ 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 2 Joanne Jennings Road Salisbury 3RN Bournemo 48 Cecil Bournemou 53 Acland Road uth BH9 1JQ 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 2 Ms Caroline Trist Avenue th BH8 9EJ Bournemo 91 St 66 Acland Road uth BH9 1JJ 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 1 Ms Susan Noone Aubyns Hove BH3 2TL 83 Bournemo Wimborne Bournemou BH3 6 Albemarle Road uth BH3 7LZ 2 0 6 6 1 0 0 1 1 0 2 Mr Nick Gheissari Road th 7AN 9 Bournemo 9 Albany Wimborne Bournemou 12a Albert Road uth BH1 1BZ 4 0 6 6 1 6 6 1 2 0 4 Rodrigo Costa Court Road th BH2 6LX 8 Albert BH12 8 Albert Road Poole BH12 2BZ 2 0 5 5 0 5 5 1 0 5 0 Lee Vine Road Poole 2BZ 1 Glenair BH14 20a Albert Road Poole BH12 2BZ 2 0 6 6 1 6 6 1 3 0 3 Mrs Anita Bowley Avenue Poole 8AD 44 Littledown Bournemou BH7 53 Albert Road Poole BH12 2BU 2 0 6 6 1 6 6 1 2 2 2 Mr Max Goode Avenue th 7AP 75 Albert BH12 75 Albert Road Poole BH12 2BX 2 0 7 7 0 7 7 1 1 1 2 Mr Mark Sherwood Road -

Internal Use Only

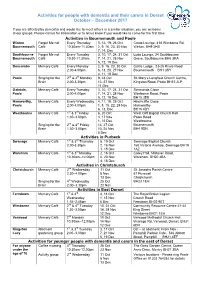

Activities for people with dementia and their carers in Dorset October – December 2017 If you are affected by dementia and would like to meet others in a similar situation, you are welcome at our groups. Please call us for information or to let us know if you would like to come for the first time. Activities in Bournemouth and Poole Winton Forget Me not Every Thursday 5, 12, 19, 26 Oct Conto Lounge, 418 Wimborne Rd, Bournemouth Café 10.30am-11.30am 2, 9, 16, 23, 30 Nov Winton, BH9 2HB 7, 14, Dec Southbourne Forget Me not Every Tuesday 3, 10, 17, 24, 31 Oct Ludo Lounge, 34 Southbourne Bournemouth Café 10.30-11.30am 7, 14, 21, 28 Nov Grove, Southbourne BH6 3RA 5, 12, 19 Dec Boscombe Memory Café Every Monday 2, 9, 16, 23, 30 Oct Curtis Lodge, 23-25 Knole Road 2.00-4.00pm 6, 13, 20, 27 Nov Bournemouth BH1 3SY 4, 11, 18 Dec Poole Singing for the 2nd & 4th Monday 9, 23 Oct St. Mary’s Longfleet Church Centre, Brain 2.00-3.30pm 13, 27 Nov Kingston Road, Poole BH15 2LP 11 Dec Oakdale, Memory Café Every Tuesday 3, 10, 17, 24, 31 Oct Simmonds Close Poole 2.00-4.00pm 7, 14, 21, 28 Nov Wimborne Road, Poole 5, 12, 19 Dec BH15 3EB Hamworthy, Memory Café Every Wednesday 4, 11, 18, 25 Oct Hinchcliffe Close Poole 2.00-4.00pm 1, 8, 15, 22, 29 Nov Hamworthy 6, 13, Dec BH15 4DY Westbourne Memory Café 1st & 3rd Friday 6, 20 Oct West Cliff Baptist Church Hall 1.30–3.00pm 3, 17 Nov Poole Road 1, 15 Dec Westbourne Singing for the 2nd & 4th Friday 13, 27 Oct Bournemouth Brain 1.30–3.00pm 10, 24 Nov BH4 9DN 8 Dec Activities in Purbeck Swanage Memory Café 1st & 3rd Thursday 5, 19 Oct Swanage Baptist Church 2.00-3.30pm 2, 16 Nov 160 Victoria Avenue, Swanage BH19 1, 15 Dec 1AZ Wareham Memory Café 1st & 3rd Monday 2, 16 Oct Carey Hall, Mistover Road, 10.30am–12.00pm 6, 20 Nov Wareham. -

The Effect of High Altitude on Central Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness

1 The effect of High Altitude on Central blood pressure and arterial stiffness 2 Christopher John Boos1,2,3, Emma Vincent4 , Adrian Mellor3-5 David Richard Woods3 4,6,7 3 Caroline New4, Richard Cruttenden4, Matt Barlow3, Mark Cooke3, Kevin Deighton3, 4 Phylip Scott4, Sarah Clarke3, John O’Hara3 5 6 1Department of Cardiology, Poole Hospital NHS Foundation trust, Poole, UK 7 2 Dept of Postgraduate Medical Education, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK 8 3Research Institute, for Sport, Physical Activity and Leisure, Leeds Beckett University, 9 Leeds, LS1 3HE, UK 10 4Defence Medical Services, Lichfield, WS14 9PY, UK 11 5James Cook University Hospital, Middlesbrough, TS4 3BW, UK 12 6Northumbria and Newcastle NHS Trusts, Wansbeck General and Royal Victoria 13 Infirmary, Newcastle, UK 14 7University of Newcastle, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK 15 Key words high altitude, central blood pressure, augmentation index, hypoxia 16 17 Corresponding author: Dr Christopher J Boos, Department of Cardiology, Poole Hospital 18 NHS Foundation Trust, Longfleet Rd. Poole, Dorset, BH15 2JB 19 Tel +44 1202 44 2572; fax +44 1202 44 2754 email: [email protected] 20 21 1 22 Central arterial systolic blood pressure (SBP) and arterial stiffness are known to be better 23 predictors of adverse cardiovascular outcomes than brachial SBP. The effect of progressive 24 high altitude (HA) on these parameters has not been examined. 25 Ninety healthy adults were included. Central BP and the augmentation index (AI) were 26 measured at the level of the brachial artery (Uscom BP+ device) at <200m and at 3619m, 27 4600m and 5140m. The average age of the subjects (70% men) were 32.2±8.7 years. -

PRACTICES ADDRESS Postcode

PRACTICES ADDRESS Postcode Denmark Road Med Centre 37 Denmark Road, Bournemouth, Dorset BH9 1PB James Fisher Med Centre 4 Tolpuddle Gardens, Bournemouth, Dorset BH9 3LQ Moordown Med Centre 2a Redhill Crescent, Bournemouth, Dorset BH9 2XF Panton Practice (Gervis Road Practice) 14 Gervis Rd, Bournemouth, Dorset BH1 3EG St Albans Med Centre 26-28 St Alban's Crescent, Bournemouth, Dorset BH8 9EW Woodlea House Surgery 1 Crantock Grove, Bournemouth, Dorset County BH8 0HS Farmhouse Surgery 1 Purewell Cross Road, Christchurch, Dorset BH23 3AF Grove Surgery Fairmile Road, Fairmile, Christchurch, Dorset BH23 2EZ Highcliffe Med Centre Heila House, 248 Lymington Road, Highcliffe, Christchurch, Dorset BH23 5ET The Christchurch Medical Centre 1 Purewell Cross Road, Christchurch, Dorset BH23 3AF Stour Surgery 49 Barrack Road, Christchurch, Dorset BH23 1PA Marine & Oakridge Pship 29 Belle Vue Road, Southbourne, Bournemouth BH6 3DB Beaufort Road Surgery 21, Beaufort Road, Bournemouth, Dorset BH6 5AJ Littledown Surgery Harewood, Bournemouth, Dorset BH7 7BU Providence Surgery 12 Walpole Road, Bournemouth, Dorset BH1 4HA Shelley Manor and Holdenhurst Med Centre Beechwood Avenue, Bournemouth, Dorset BH5 1LX Southbourne Surgery 17 Beaufort Road, Bournemouth, Dorset BH6 5BF Alma Partnership 31 Alma Road, Bournemouth, Dorset BH9 1BP Banks & Bearwood Med Practice 272 Wimborne Road, Bournemouth BH3 7AT Kinson Road Med Centre 440, Kinson Road, Bournemouth, Dorset BH10 5EY Leybourne Surgery 1, Leybourne Avenue, Bournemouth, Dorset BH10 6ES Talbot Med Centre 63 Kinson -

DORSETSHIRE. [KELLV's

158 POOLE. DORSETSHIRE. [KELLV's Masonic Hall, 54 Market st. Alfred Durant, caretaker Collector of King's Taxes for the Borough of Poole, Geo. Oddfellows' Hall, Hunger hill, Cha.s. Sansom, caretaker Stout, 238 Ashley r1>ad, Branksome, Parkstone Pilot Office, William Stone, pilot in charge, Quay · Lloyd's Agent, Henry Burden, Wes·t :Shore wharf, West Public Free Library. Mount street, Edwin R1 Gill Quay road .A..R.C.A. sec. & librarian Registrar of Bankruptcy, Admiralty & Equity Jurisdlc Royal National Lifeboat Institution (Poole & Bourne tion, Hugh Fol"tescue Wilmslhurst Gwatkin,Ioo High at mouth Branch), East quay, H. E. ShQve, hon. sec Registrar of the Royal Peculiar Oourt; of Great Canford, Stamp Office, 71 High st. Chas, John Woodford,distributr Hugh Fortescue Wilmshurst Gwat.ltin, 100 High stre11t Temperance Hall, r7 Hill st. Wm. Jaa. Hickman, sec Sub-Commissioners of Pilotage for the Port of Poole, Charles Leonard Barrett (sec.), Custom house, Quay; POOLE UNION. John Mowlem, The Old farm, Parkstone rd. & Alfred Board day, every alternate wednesday, at the Board room, Langlois, Maxwell villa, Longfleet road, Longfleet workhouse The union 'COmprises the following parishes :-Canfdrd PLJ.CES OF WORSHIP, with times of Services. Magna, Kinson, Lytchett Matravers, Lytchett Minster St. James's Church, Rev. Henry Lawrence PhiUip,, ' & ,Poole. The area is 25,326 acres; rateable value, rector; 8 & n a.m. & 6.30 ;p.m.; •aints' days k 'Lady Day, r9n, £214,437; the population in 1911 holy days, II a. m. ; wed. II a.m. & 7 p.m.; fri. was 45,191 11 a.m Chainnan of the Board of Guardians, G. -

List of Neurocentres in the UK

List of Neurocentres in the UK Contents • Neurosurgery: p 1 • Neurology departments: p 5 • Radiosurgery and Radiotherapy: p 8 • Spinal Injuries Units: p 10 Neurosurgery Please see below a list of neurosurgery centres in the UK. Neurosurgery centres undertake neurosurgery, in addition to providing general neurology services. East England Addenbrooke's Hospital Hills Road Cambridge CB2 0QQ Queen's Hospital Rom Valley Way Romford Essex RM7 0AG East Midlands Queen's Medical Centre Derby Road Nottingham NG7 2UH Greater London Charing Cross Hospital Fulham Palace Road London W6 8RF Cromwell Hospital (private) Cromwell Road London SW5 0TU 1 Kings College Hospital Denmark Hill London SE5 9RS The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery Queen Square London WC1N 3BG The Royal Free Pond Street London NW3 2QG Barts and the London Centre for Neurosciences Royal London Hospital Whitechapel Road London E1 1BB St George's Hospital Blackshaw Road London SW17 0QT The Wellington Hospital (private) Wellington Place London NW8 9LE North East England James Cook University Hospital Marton Road Middlesbrough TS4 3BW Regional Neurosciences Centre, Royal Victoria Infirmary Queen Victoria Road Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4LP North West England Greater Manchester Neurosciences Centre Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust Stott Lane Salford M6 8HD 2 Royal Preston Hospital Sharoe Green Lane Fulwood Preston PR2 9HT Chorley and South Ribble Hospital Preston Road Chorley PR7 1PP The Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery Lower Lane Fazakerley Liverpool L9 7LJ South -

Heckford Park Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan

Heckford Park Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan Planning and Regeneration Services, 2010 Public Consultation & Adoption The consultation draft was issued December 009 and was the subject of an eight week public consultation. The resulting changes were agreed by the Council and the document was adopted by the Borough of Poole on 8th June 010. This document forms part of the evidence base for the Local Development Framework for Poole and development proposals will be reviewed according to four key documents including: • Poole Local Plan First Alteration (adopted March 004) • Poole Core Strategy adopted 19th February 009 • The Southwest Regional Spatial Strategy (public consultation) July 008 • Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole Structure Plan 004 The Poole Local Plan policies included in this document are under review and will be replaced as part of the Poole Core Strategy revisions. Heckford Park Conservation Areas Appraisal and Management Plan: Publication Details The purpose of this document To provide an analysis of the character and appearance of the Heckford Park Conservation Area in accordance with Section 71 of The Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 and to formulate and publish proposals for the preservation and enhancement of Conservation Areas. The appraisal and management proposals are intended to act as guidance to residents, planners, agents and developers in order to manage future changes and development proposals within the Conservation Areas in ways that preserve or enhance their character or appearance. Production Team Stephen Thorne Head of Planning & Regeneration Services Warren Lever Environment & Design Team Leader Hazel Brushett Conservation Officer Design: Borough of Poole Adopted: 6th December 2010 Further information Planning and Regeneration Services: Civic Centre Poole BH15 RU Tel. -

Department of Anaesthesia Poole Hospital NHS Trust Longfleet Road Poole Dorset BH15 2JB

Department of Anaesthesia Poole Hospital NHS Trust Longfleet Road Poole Dorset BH15 2JB 18th April 2007 To : All Clinical Leads in Obstetric Anaesthesia Dear Colleague, The last triennial CEMACH report recommended the introduction of an Early Warning Scoring System (EWS) in obstetrics to allow the early detection of clinical deterioration of patients. We are not aware of any validated obstetric EWS and would like to try and find out if any such system exists in the UK and perhaps to suggest an EWS based on modification of those already in use for the non-obstetric population. Current evidence suggests that the majority of admissions to critical care for obstetric patients are due to hypertensive disease or haemorrhage. We have attempted to adapt our local non-obstetric EWS to take into account the physiological changes of pregnancy. We are extremely interested in your views and comments with regard to obstetric early waning systems as a whole, and would be very grateful if you would spare a few moments of your time to consider the enclosed questionnaire. When you have completed the questionnaire, please return it in the enclosed stamped address envelope. Many thanks for your time, Yours sincerely, Dr Rob Swanton (SpR, Poole Hospital) Dr Samar Al-Rawi (SpR, Southampton Hospital) Dr Mike Wee (Consultant Anaesthetist & Obstetric Anaesthetic Lead, Poole Hospital) References 1. Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health : Why Mothers Die 2000-2002 2. Parissopoulos S, Kotabassaki S. Critical Care Outreach and the use of the Early Warning Scoring Systems – a Literature Review. ICUS Nurs Web J 2005; 21: 1-13 3. -

Descendant Chart for William Beckingham

Descendant Chart for William Beckingham William Beckingham Magdelen Woodward b: Abt 01 Jan 1548 b: d: Jan 1613 in Lambourn, Berkshire; d: Bockhampton, m: 12 Nov 1571 in St Michael & All Angels, Lambourn, Berkshire Marie Beckingham Lawrence Beckingham 2 b: Abt 1573 in Lambourn, Berkshire b: Abt 1574 in Lambourn, Berkshire d: Feb 1574 in Lambourn, Berkshire d: Apr 1575 in Lambourn, Berkshire Page 1 William Beckingham Magdelen Woodward b: Abt 01 Jan 1548 b: d: Jan 1613 in Lambourn, Berkshire; d: Bockhampton, m: 12 Nov 1571 in St Michael & All Angels, Lambourn, Berkshire 1 Elizabeth Beckingham Thomas James 3 b: Abt 1575 in Lambourn, Berkshire b: d: d: m: 08 Aug 1597 in St Michael & All Angels, Lambourn, Berkshire Elizabeth James Thomas James Phillip James Christian James b: Abt 1598 in Lambourn, Berkshire b: Abt 1599 in Lambourn, Berkshire b: Abt 1612 in Lambourn, Berkshire b: Abt 1613 in Lambourn, Berkshire; d: d: d: Bockhold, d: Page 2 William Beckingham Magdelen Woodward b: Abt 01 Jan 1548 b: d: Jan 1613 in Lambourn, Berkshire; d: Bockhampton, m: 12 Nov 1571 in St Michael & All Angels, Lambourn, Berkshire 2 John Beckingham Joan 28 b: Abt 1576 in Lambourn, Berkshire b: d: Bef. 1636 ; Joan remarries d: m: Abt 1607 4 Page 3 3 John Beckingham Joan b: Abt 1576 in Lambourn, Berkshire b: d: Bef. 1636 ; Joan remarries d: m: Abt 1607 John Beckingham Christiana Henry Beckingham 5 b: Abt 1607 in East Garston, Berkshire b: b: Abt 1610 in Hungerford, Berkshire; Great d: Bef. 1670 d: Nov 1684 in Inkpen, Berkshire Hidden m: Bef.