Portland Development Commission: Governance, Structure and Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voters' Pamphlet

Washington Elections Division 3700 SW Murray Blvd. Beaverton, OR 97005 County www.co.washington.or.us voters’ pamphlet VOTE-BY-MAIL PRIMARY NOMINATING ELECTION May 20, 2008 To be counted, voted ballots must be in our office by 8:00 pm on May 20, 2008 Washington County Dear Voter: Board of County This pamphlet contains information for several dis- Commissioners tricts and there may be candidates/measures included that are not on your ballot. If you have any questions, Tom Brian, Chair call 503-846-5800. Dick Schouten, District 1 Desari Strader, District 2 Roy Rogers, District 3 Attention: Andy Duyck, District 4 Washington County Elections prints information as submitted. We do not correct spelling, punctuation, grammar, syntax, errors or inaccurate information. W-2 W-3 W-4 WASHINGTON COUNTY Commissioner, District 3 Roy R. Rogers (Nonpartisan) OCCUPATION: Certified Public Accountant /County Commissioner OCCUPATIONAL BACKGROUND: Managing Partner of large local firm. EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Portland State University; Bachelor of Science Degree; Numerous additional courses in finance, management, and public finance. PRIOR GOVERNMENTAL EXPERIENCE: County Commissioner (current); Mayor, City of Tualatin (3 terms); President Oregon Mayors Association; Clean Water Services Board; Numerous State, Regional and County Transportation and Planning Committees; Board Member of Enhanced Sheriffs Patrol, Urban Road Maintenance and Housing Authority Districts ROY IS INVOLVED! • Tigard First Citizen • Past President - Tigard Rotary, Tigard Chamber, Tigard -

Lake Oswego Portland

Lake Oswego to Portland TRANSIT PROJECT Public scoping report August 2008 Metro People places. Open spaces. Clean air and clean water do not stop at city limits or county lines. Neither does the need for jobs, a thriving economy and good transportation choices for people and businesses in our region. Voters have asked Metro to help with the challenges that cross those lines and affect the 25 cities and three coun- ties in the Portland metropolitan area. A regional approach simply makes sense when it comes to protecting open space, caring for parks, planning for the best use of land, managing garbage disposal and increasing recycling. Metro oversees world-class facilities such as the Oregon Zoo, which contributes to conservation and educa- tion, and the Oregon Convention Center, which benefits the region’s economy Metro representatives Metro Council President – David Bragdon Metro Councilors – Rod Park, District 1; Carlotta Collette, District 2; Carl Hosticka, District 3; Kathryn Harrington, District 4; Rex Burkholder, District 5; Robert Liberty, District 6. Auditor – Suzanne Flynn www.oregonmetro.gov Lake Oswego to Portland Transit Project Public scoping report Table of contents SECTION 1: SCOPING REPORT INTRODUCTION …………………………………......... 1 Introduction Summary of outreach activities Summary of agency scoping comments Public comment period findings Conclusion SECTION 2: PUBLIC SCOPING MEETING ………………………………………………… 7 Summary Handouts SECTION 3: AGENCY SCOPING COMMENTS ………………………………………..... 31 Environmental Protection Agency SECTION 4: PUBLIC -

Voters Pamphlet.Qxd

MULTNOMAH COUNTY VOTERS’ PAMPHLET PRIMARY ELECTION - MAY 16, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS CANDIDATES: CITY OF PORTLAND MISCELLANEOUS: MULTNOMAH COUNTY Commissioner, Position #2 M-12 Voters’ Information Letter M-2 County Commissioner, Chair M-3 Commissioner, Position #3 M-14 Multnomah County Map M-28 County Commissioner, District #2 M-4 Auditor M-16 Metro Map M-29 County Auditor M-6 MEASURES: Drop Site Locations M-30 County Sheriff M-7 City of Wood Village (#26-76) M-17 Library Drop Sites M-31 METRO City of Troutdale (#26-77) M-19 Making It Easy To Vote M-32 Metro Council President M-9 Multnomah County (#26-78) M-22 Metro Auditor M-9 Corbett School District #39 (#26-79) M-23 Metro Councilor, Position #1 M-10 Scappoose R.F.P.D. (#5-144) M-25 Metro Councilor, Position #2 M-11 Beaverton School District #48 (#34-115) M-27 ATTENTION This is the beginning of your county voters’ pamphlet. The county portion of this voters’ pamphlet is inserted in the center of the state portion. Each page of the county voters’ pamphlet is clearly marked with a black bar on the outside edge. All information contained in the county portion of this pamphlet has been assembled and printed by your County Elections Official. Multnomah County Elections This pamphlet produced by: 1040 S.E. Morrison Street Portland, Oregon 97214-2495 # www.mcelections.org M-1 MULTNOMAH COUNTY OREGON DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY SERVICES BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS JOHN KAUFFMAN, DIRECTOR OF ELECTIONS DIANE LINN • CHAIR OF THE BOARD 1040 SE MORRISON ST MARIA ROJO de STEFFEY • DISTRICT 1 COMMISSIONER PORTLAND, OREGON 97214 SERENA CRUZ • DISTRICT 2 COMMISSIONER (503) 988-3720 Phone LISA NAITO • DISTRICT 3 COMMISSIONER (503) 988-3719 Fax LONNIE ROBERTS • DISTRICT 4 COMMISSIONER Web Site: www.mcelections.org Dear Multnomah County Voter: You are about to receive your ballot in the mail and there are a few things you should know: • Voted ballots MUST be received at our office or drop site location by 8:00 PM, Tuesday, May 16, 2006 to be counted. -

Stay Home, Stay Safe, Vote by Mail! Using the Return Envelope (Free Postage), and Mailed Back by May 14, 2020

Stay home, Stay safe, Vote by Mail! Using the return envelope (free postage), and mailed back by May 14, 2020. Or, any Official Ballot Drop site in Oregon by 8:00 p.m., May 19, 2020. Dear Multnomah County Voter: This Voters’ Pamphlet for the May 19, 2020 Primary Election is Multnomah County being mailed to residential households in Multnomah County. Here are a few things you should know: Voters’ Pamphlet • You can view your registration status at oregonvotes.gov/myvote. There you can update your voter registration or track your ballot. May 19, 2020 The Voter Registration/Party Change Deadline is April 28, 2020. Primary Election • If you wish to vote for the Democratic or Republican Party candidates in the May Primary you must register with one of __________________ those parties by the Voter Registration/Party Change deadline, April 28, 2020. Multilingual Voting • You can choose or change your party by updating your voter registration information online (with Oregon DMV ID) Information Inside oregonvotes.gov/myvote or filling out an Oregon Voter Registration Card. The Voter Registration/Party Choice Deadline Información de votación en el is April 28, 2020. interior del panfleto • If you are registered with the Democratic or Republican party you Информация о процессе will also receive a precinct committeeperson ballot, however голосовании приведена внутри precinct committee candidates do not appear in this Voters’ Bên Trong Có Các Thông Tin Về Pamphlet. Việc Bỏ Phiếu • If you change your party affiliation near the April 28, 2020 投票信息请见正文。 deadline you may receive two ballots Vote only the second ballot with your new party. -

French Prairie Bridge

Table of Contents 1. Summary of Key Attributes: Emergency Link for I-5 Historical Context & Topography Regional TTrail Connections 2. Media Coverage: French Prairie Articles Opinion Editorials Bike-Ped Emergency 3. Supporters: Governments Bridge Organizations 4. Master Plan Excerpts: Briefing Booklet 1993 Bicycle and Pedestrian 1994 Parks & Recreation ______________________ 2007 Bicycle, Pedestrian and Transit March 2012 5. Public Involvement: Master Planning Efforts History of Public Input Planning Commission Metro MTIP Award Process 1. Summary of Key Attributes: Emergency Link for I-5 Historical Context & Topography Regional Trail Connections WILSONVILLE, OREGON French Prairie Bridge Regional Significance PORTLAND Reconnecting the missing, historic Willamette River link of the Portland see inset map WILSONVILLE area with the Willamette Valley k Champoeg State Park Key Attributes of the Proposed French Prairie Bridge at Wilsonville • Historic route reestablished at Boones Ferry crossing, linking the French Prairie region of the north Willamette SALEM Valley to the greater Portland metro area. • Safe bicycle and pedestrian access across the Willamette River without the hazards of using I-5. • Improved connectivity between the Willamette Valley Scenic Bikeway and new Portland area Tonquin Trail. ALBANY • Emergency access to highway accidents for police, fire and CORVALLIS safety vehicles responding to incidents occurring on I-5. • Tourism development opportunities featuring French Prairie, the Willamette River Greenway, -

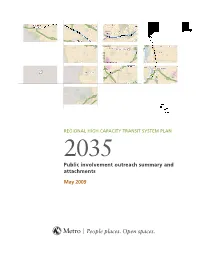

Public Involvement Outreach Summary and Attachments

17D Portland Christian HS Oregon Graduate Institute 12 Capital Center 17A Sunset HS Cedar Mill Sylvan Learning Ctr Tualatin Valley Jr Academy Transit Center Central Catholic HS David Douglas HS Catlin Gabel HS Portland State Portland Adventist Academy 32A Century HS University Aloha 32A Franklin HS Hillsboro HS Oregon Health & Science University Cleveland HS 10A 32A 11A Valley Catholic HS Aloha HS Jesuit HS Raleigh Hills 10 11T Hillsdale Reed College 48 Washington Riverdale HS Southridge HS 11C Lewis & Clark 5 College Milwaukie 219 Milwaukie HS Murray Hill Tigard PCC - Sylvania Lake Oswego HS 29A Lake 99 E 99 W New Urban Clackamas HS High School King City 224 Putnam HS LEGEND Lakeridge HS Marylhurst University 9 11E 38S Gladstone HS HCT Corridors 43 Gladstone 28B West Linn corridors) Tualatin HS Sherwood HS LEGEND 205 Oregon City Oregon City HS rg e b High Capacity Transit (2009) w e N o Planned High Capacity Transit T neighboring cities to be measured by travel demand) N Clackamas Christian HS Newberg Senior HS REGIONAL HIGH CAPACITY TRANSIT SYSTEM PLAN 213 Wilsonville HS Railroad Wilsonville School Parks/Open Space 2035 Public involvement outreach summary and attachments May 2009 Introduction The High Capacity Transit System Plan is as a blueprint for high capacity transit (HCT) investments for the next 30 years in the Portland metro region. The plan will be adopted as part of the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP), identifying corridors for future investments in a tiered priority. A related system expansion policy will guide Metro and local jurisdictions in future assessment prioritization and project development by providing targets to improve priority standing. -

2004 Regional Transportation Plan Appendix

Appendix 2004 Regional Transportation Plan July 8, 2004 Metro People places • open spaces Metro serves 1.3 million people who live in Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington counties and the 25 cities in the Portland metropolitan area. The regional government provides transportation and land-use planning services and oversees regional garbage disposal and recycling and waste reduction programs. Metro manages regional parks and greenspaces and owns the Oregon Zoo. It also oversees operation of the Oregon Convention Center, the Portland Center for the Performing Arts and the Portland Metropolitan Exposition (Expo) Center, all managed by the Metropolitan Exposition Recreation Commission. Your Metro representatives Metro Council President – David Bragdon Metro Councilors – Rod Park, District 1; Brian Newman, District 2; Carl Hosticka, District 3; Susan McLain, District 4; Rex Burkholder, District 5; Robert Liberty, District 6. Auditor – Alexis Dow, CPA Metro’s web site: www.metro-region.org Metro 600 NE Grand Ave. Portland, OR 97232-2736 (503) 797-1700 Printed on 100 percent recycled paper, 30 percent post-consumer fiber 2004 Regional Transportation Plan Technical Appendix Table of Contents 1.0 RTP System Development and Analysis 1.1 Illustrative, Priority and Financially Constrained Project Lists 1.2 System Performance Summary Tables 1.3 Principles for System Development 1.4 2020 No-Build System Assumptions 1.5 2020 Existing Resources System Assumptions 1.6 Highway Capacity Manual Level of Service Table 1.7 2020 and 2025 Population and Employment -

Meeting Notes 2005-12-15

Portland State University PDXScholar Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 12-15-2005 Meeting Notes 2005-12-15 Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_jpact Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation, "Meeting Notes 2005-12-15 " (2005). Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation. 422. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_jpact/422 This Minutes is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. _A G E N D A_ 600 NORTHEAST GRAND AVENUE PORTLAND, OREGON 97232-2736 JPACT RECORD-KEEPER METRO METRO TEL 503-797-1916 FAX 503-797-13JU MEETING: JOINT POLICY ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON TRANSPORTATION DATE: December 15, 2005 TIME: 7:30 A.M. PLACE: Council Chambers, Metro Regional Center 7:30 CALL TO ORDER AND DECLARATION OF A QUORUM Rex Burkholder, Chair 7:30 INTRODUCTIONS Rex Burkholder, Chair 7:35 CITIZEN COMMUNICATIONS 7:40 COMMENTS FROM THE CHAIR Rex Burkholder, Chair 7:45 CONSENT AGENDA Rex Burkholder, Chair Consideration of JPACT minutes for October 13, 2005 and November 10, 2005 DISCUSSION ITEMS ** Cost of Congestion debrief - INFORMATION Jon Coney, Metro Direction of FY07 Appropriations Requests - DISCUSSION Andy Cotugno, Metro * RTP Update - INFORMATION Kim Ellis, Metro Corridors Letter from Metro Council - DISCUSSION Rex Burkholder, Chair Robert Liberty, Metro * Resolution 06-3651, FOR THE PURPOSE OF AMENDING Andy Cotugno, Metro THE FY06 UNIFIED PLANNING WORK PROGRAM (UPWP) - JPACT APPROVAL REQUESTED OTHER COMMITTEE BUSINESS Rex Burkholder, Chair 9:00 ADJOURN Rex Burkholder, Chair Material available electronically. -

In the Supreme Court of Ohio

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF OHIO John Michael Fitzpatrick, ^ 7 - 1231 Relator, v. Petition For Writ Of Mandamus Original Action Hon. Kathleen Aubry, Respondent. PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS John Michael Fitzpatrick, Relator 7309 Fall Creek Lane Columbus, Ohio 43235 614.678.4559 [email protected] Hon. Kathleen Aubry, Respondent Wyandot County, Ohio Common Pleas Court Judge 109 South Sandusky Street Upper Sandusky, Ohio 43351 419.294.1727 1. On the 5`h day of July 2007, Scott Williams, Plaintiff in Williams v. Williams, case no. 06 DR 0105, filed in the Common Pleas Court of Wyandot County, Ohio, a motion seeking to bar contact between 27 month old Neil Franklin Williams and John Michael Fitzpatrick. See plaintiffs motion exhibit one. See defendant's opposition exhibit two. 2. On the 6`h day of July 2007, Common Pleas Court Judge Kathleen Aubry granted Plaintiff's motion barring contact between the minor child and Relator, casting a false light on John Michael Fitzpatrick as a promoter of sexual deviancy. See Judgment exhibit three. 3. Plaintiffs Motion cited the sexually explicit contents of a videotape production by Relator entitled "HOW SAY YOU, JURY NULLIFICATION IN AMERICA" which was twice cablecast in West Hollywood, California and has not been the subject of crin-unal court proceedings nor been found obscene. Judge Aubry stated she "viewed the tape and found that interspersed in a long discourse with a First Amendment Attorney, were clips of pomographic material which appeared to be gratuitous and unnecessary to understand the topic." Perhaps Judge Aubry is so familiar with images of bestiality and transsexual oral copulation that mere mention would suffice (absent the images themselves), but most members of the viewing (and voting) public are not that well informed. -

Making History: 50 Years of Transit in the Portland Region

MAKING HISTORY 50 Years of TriMet and Transit in the Portland Region MAKING HISTORY 50 YEARS OF TRIMET AND TRANSIT IN THE PORTLAND REGION Prepared by the Tri-County Metropolitan Transportation District of Oregon with encouragement from Congressman Earl Blumenauer Philip Selinger, Author and Researcher Angela Murphy, Editor and Project Manager Melissa Schmidt Morley, Graphic Designer With special appreciation to reviewers, contributors and TriMet support staff: Steve Morgan JC Vannatta Roberta Altstadt Alan Lehto Bernie Bottomly Debbie Huntington Thomas Gelsinon Steve Dotterrer Richard Feeney Rick Gustafson Neil McFarlane Special thanks to TriMet’s Communications Department staff for the numerous releases, announcements and reports from which material was sourced. We acknowledge and thank the contributors from the 45th Anniversary publication: Sandy Vinci, Philip Selinger, Janet Schaeffer, Laura Eddings, Andy Cotugno, Steve Dotterrer, Richard Feeney, Rick Gustafson, Bruce Harder, Tom Markgraf, Neil McFarlane, Ann Becklund, Bernie Bottomly, Mary Fetsch, Debbie Huntington, JC Vannatta, Steve Morgan, Carl Abbott, Sy Adler and Ethan Seltzer © TriMet, Portland, Oregon, 2019. Making History: 50 Years of TriMet and Transit in the Portland Region is available at trimet.org/makinghistory. Please check the web edition for updates. 190143 • 4M • 10/19 CONTENTS Foreword: 50 Years of Transit Creating Livable Communities . 1 Setting the Stage for Doing Things Differently . 2 Portland, Oregon’s Legacy of Transit . 4 Beginnings ............................................................................4 -

![Meeting Notes 2000-07-13 [Part C]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7591/meeting-notes-2000-07-13-part-c-8277591.webp)

Meeting Notes 2000-07-13 [Part C]

Portland State University PDXScholar Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation Oregon Sustainable Community Digital Library 7-13-2000 Meeting Notes 2000-07-13 [Part C] Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_jpact Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation, "Meeting Notes 2000-07-13 [Part C] " (2000). Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation. 304. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/oscdl_jpact/304 This Minutes is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Draft June 29, 2000 2000 Regional Transportation Plan Public Comment Report Summary of public comments received between May 15, 2000-June 29, 2000 METRO Regional Services Creating livable Metro Executive Officer Protecting the nature of our region Mike Burton Auditor "It's better to plan for growth than ignore it." Alexis Dow, CPA Planning is Metro's top job. Metro provides a regional Council forum where cities, counties and citizens can resolve issues related to growth - things such as protecting Presiding Officer streams and open spaces, transportation and land-use District 7 choices and increasing the region's recycling efforts. David Bragdon Open spaces, salmon runs and forests don't stop at city limits or county lines. Planning ahead for a healthy environment and stable economy supports livable Deputy Presiding Officer communities now and protects the nature of our region District 5 for the future. -

2008 Regional Solid Waste Management Plan

Regional Solid Waste Management Plan 2008 - 2018 Update Plan adopted by Ordinance No. 07-1162A, July 24, 2008. Chapter VI. Section I. Plan compliance and enforcement, amended by Ordinance No. 08-1198, Sept. 18, 2008. Metro People places • open spaces Clean air and clean water do not stop at city limits or county lines. Neither does the need for jobs, a thriving economy and good transportation choices for people and businesses in our region. Voters have asked Metro to help with the challenges that cross those lines and affect the 25 cities and three counties in the Portland metropolitan area. A regional approach simply makes sense when it comes to protecting open space, caring for parks, planning for the best use of land, managing garbage disposal and increasing recycling. Metro oversees world-class facilities such as the Oregon Zoo, which contributes to conservation and education, and the Oregon Convention Center, which benefi ts the region’s economy. Your Metro representatives Metro Council President – David Bragdon Metro Councilors District 1, Rod Park District 2, Carlotta Collette District 3, Carl Hosticka District 4, Kathryn Harrington District 5, Rex Burkholder District 6, Robert Liberty Auditor – Suzanne Flynn Metro’s web site - www.oregonmetro.gov Contents Executive Summary ......................................................1 Table 1. Recovery by generator source ......................10 Table 2. Top fi ve haulers ...........................................12 Chapter I, Introduction ................................................3 Table 3. Transfer station throughput and A. Why a Regional Plan? estimated capacity. ......................................14 B. Plan Context Table 4. Landfi ll ownership and approximate C. Scope of Plan reserve capacity. ..........................................17 D. The Planning Process Table 5.