The Roots of Musical Variation in Perceptual Similarity and Invariance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC San Diego. Center for Research in Computing and the Arts Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8h41ptz No online items UC San Diego. Center for Research in Computing and the Arts Collection Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2012 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html UC San Diego. Center for RSS 1225 1 Research in Computing and the Arts Collection Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: UC San Diego. Center for Research in Computing and the Arts Collection Identifier/Call Number: RSS 1225 Physical Description: 3.6 Linear feet(8 archives boxes and 1 card file box) Date (inclusive): 1969-2012 Abstract: The UCSD Center for Research in Computing and the Arts (CRCA) collection documents the activities of the experimental music and computer-based music research unit between 1972-1993. Admisistrative History The Project for Music Experiment, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, opened in 1972 under the direction of UCSD professor Roger Reynolds. In 1973, the project became an organized research unit at the University of California, San Diego and was re-named the Center for Music Experiment (CME). Although autonomous, the Center was monitored by an inter-departmental advisory board with UCSD Music Department faculty. The director was nominated by the board and appointed by the Chancellor for terms up to five years. The Center was designed as a performance, composition, and a technological research space for innovations with digital computer music. The Center also facilitated the Studio for Extended Performance, the Extended Vocal Techniques Ensemble (EVTE), and the KIVA Improvisation Ensemble. -

Of Music PROGRAM

FESTIVAL OF AMERICAN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC at Rice University November 2-8, 1992 celebrating American Music Week CHAMBER MUSIC OF ROSS LEE FINNEY Tuesday, November 3, 1992 8:00p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall ~herd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~l Of Music PROGRAM Sonata No. 2 in C for cello and piano (1950) Ross Lee Finney Introduction (Adagio espressivo) (b. 1906) Allegro con brio Adagio arioso Prestissimo Samuel McGill, cello John Hendrickson, piano Quartet for oboe, cello, Ross Lee Finney percussion and piano (1969) -Prologue - I. Allegro moderato - Interlude - II. Allegro capriccioso Janet Rarick, oboe Michael Dudley, cello Richard Brown, percussion John Hendrickson, piano INTERMISSION Selections from Chamber Music (1951) Ross Lee Finney (Text by James Joyce) III. At that hour when all things have repose ... VIII. Who goes amid the green wood ... XV. From dewy dreams, my soul, arise ... XVIII. 0 Sweetheart, hear you your lover's tale ... XIX. Be not sad ... XXIII. This heart that flutters near my heart ... XXV. Lightly come or lightly go ... XXX. Love came to us in time gone by .. XXXIII. Now, 0 now, in this brown land .. XXXIV. Sleep now, 0 sleep now, 0 you unquiet heart! ... XXXVI. I hear an army charging upon the land ... Jeanette Lombard, soprano Jeanne Kierman, piano Quintet for Piano and Strings (1953) Ross Lee Finney Adagio sostenuto; Allegro marcato Allegro scherzando Nocturne: Adagio sostenuto Allegro appassionato Kenneth Goldsmith, violin I Julie Savignon, violin II Csaba Erdelyi, viola Norman Fischer, cello Jeanne Kierman, piano BIOGRAPHY For more than fifty years, ROSS LEE FINNEY has been prominent both as a composer and as a teacher. -

Comp Prog Info MM 8-11

FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC Masters of Music Composition The Florida International University MM in Music Composition Program Philosophy and Mission Statement. The MM in Composition at Florida International University is designed to assist students with the development of their own individual voices as composers while helping them to continue to develop their craft. Numerous performance opportunities of students’ works by excellent performers and ensembles as well as hands on experience in the use of new technologies including computer music, video, and interactive and notational software are an integral part of the curriculum. Many of our graduates have continued studies at other prestigious schools and have been the recipients of ASCAP and BMI Student Composition awards. The two- year MM in composition prepares composers for either continued graduate studies or as skillful composers continuing in a variety of other related occupations. For more information regarding the program contact: Dr. Orlando Jacinto Garcia, Director Music Composition Florida International University School of Music WPAC 141 University Park Miami, Florida 33199 phone (305) 348-3357; fax (305) 348-4073 email: [email protected] School of Music web page: music.fiu.edu Rev 8/11 ADMISSION AND GENERAL REQUIREMENTS (Effective fall 2011) Admission into the composition program is contingent upon the approval of the composition faculty and is dependent upon the applicant’s portfolio and previous undergraduate course work. A minimum 3.0 GPA in the student’s last 60 credits of undergraduate work is also required for admittance. Students should have a BM degree in music composition or the equivalent. After initial admission to the program, students will be required to pass history and theory placement tests and if necessary do remedial work in these areas. -

A Study of the Spatial Aspects of Edgard Varèse's Work, Part II

g e n e r a l a r t i c l e The Last Word Is: Imagination A Study of the Spatial Aspects of Edgard Varèse’s Work, Part II: Visual Evidence R o g e R R e y n o L d S Edgard Varèse was one of the singular musical innovators of the creative aspirations and barriers to their fulfillment (techno- 20th century. Central to his thinking was an informed yet uniquely logical, contextual, logistical), it is useful to consider what imaginative position regarding metaphoric “space.” Through contacts he did in situations over which he had unimpeded control. with science, he developed an idiosyncratic vocabulary involving ABSTRACT “rotating planes,” “beams,” “projection” and “penetration.” His This was not the case in the realm of musical composition outlook was both conceptually and musically (especially in Intégrales) because limitations of performance capacity, as well as the manifested. The first part of a two-part article, “The Last Word Is: available strategies for the electronic manipulation and dis- Imagination, Part I: The Visual Evidence” (published in Perspectives of semination of sound, thwarted the demands of his imagina- New Music), references Varèse’s writings and lectures. The second tion. But in other ways, his work—musical sketches, graphic part, published here, is concerned with the visual evidence, a context art, marginalia, doodles and diagrams to be found among his within which his spatial ideas could be directly manifested without the distortions of electroacoustic sound projection or vagaries of instrumental materials in the Sacher Archives—manifests directly the ways and vocal performance. -

PRINTABLE PROGRAM Bernard Rands

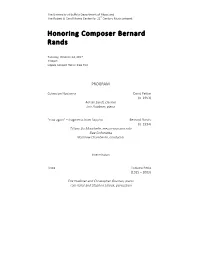

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Honoring Composer Bernard Rands Tuesday, October 24, 2017 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Coleccion Nocturna David Felder (b. 1953) Adrián Sandí, clarinet Eric Huebner, piano "now again" – fragments from Sappho Bernard Rands (b. 1934) Tiffany Du Mouchelle, mezzo-soprano solo Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Intermission Linea Luciano Berio (1925 – 2003) Eric Huebner and Christopher Guzman, piano Tom Kolor and Stephen Solook, percussion Folk Songs Bernard Rands I. Missus Murphy’s Chowder II. The Water is Wide III. Mi Hamaca IV. Dafydd Y Garreg Wen V. On Ilkley Moor Baht ‘At VI. I Died for Love VII. Über d’ Alma VIII. Ar Hyd y Nos IX. La Vera Sorrentina Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Slee Sinfonietta Matthew Chamberlin, conductor Emlyn Johnson, flute Erin Lensing, oboe Adrián Sandí, clarinet Michael Tumiel, clarinet Jon Nelson, trumpet Kristen Theriault, harp Eric Huebner, piano Chris Guzman, piano Tom Kolor, percussion Steve Solook, percussion Tiffany Du Mouchelle, soprano (solo) Julia Cordani, soprano Minxin She, alto Hanna Hurwitz, violin Victor Lowrie, viola Katie Weissman, ‘cello About Bernard Rands Through a catalog of more than a hundred published works and many recordings, Bernard Rands is established as a major figure in contemporary music. His work Canti del Sole, premiered by Paul Sperry, Zubin Mehta, and the New York Philharmonic, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize in Music. His large orchestral suites Le Tambourin, won the 1986 Kennedy Center Friedheim Award. His work Canti d'Amor, recorded by Chanticleer, won a Grammy award in 2000. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1965-1966

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 1966 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation I " STMVINSKY tt.VlOW agon vam 7/re Boston Symphony SCHULLER 7 STUDIES ox THEMES of PAUL KLEE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA/ERICH lEINSDORf under Leinsdorf Leinsdorf expresses with great power the vivid colors of Schuller's Seven Studies on Themes of Paul Kiee and, in the same album, Stravinsky's ballet music from Agon. Forthe majorsinging roles in Menotti's dramatic cantata, The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi. Leinsdorf astutely selected George London, and Lili Chookasian, of whom the Chicago Daily Tribune has written, "Her voice has the Boston symphony ecich teinsooof / luminous tonal sheath that makes listening luxurious. menotti Also hear Chookasian in this same album, in songs from the death op the Bishop op BRSndlSI Schbnberg's Gurre-Lieder. In Dynagroove sound. Qeonoe ionoon • tilt choolusun s<:b6notec,/ou*«*--l(eoeo. sooq of the wooo-6ove ac^acm rca Victor fa @ The most trusted name in sound ^V V BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH LeinsDORF, Director Joseph Silverstein, Chairman of the Faculty Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Emeritus Louis Speyer, Assistant Director Victor Babin, Chairman of the Tanglewood Institute Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM Contemporary Music Activities Gunther Schuller, Head Roger Sessions, George Rochberg, and Donald Martino, Guest Teachers Paul Zukofsky, Fromm Teaching Fellow James Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Viola C Aliferis, Assistant Administrator The Berkshire Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. -

Bernard Rands

NWCR591 Bernard Rands 1. Canti Lunatici (1980) * ....................................... (28:20) 2. Canti del Sole (1982) **....................................... (25:15) *Carol Plantamura, soprano; **Paul Sperry, tenor SONOR Ensemble of the University of California, San Diego: John Fonville, flute; William Powell, clarinet; Edwin Harkins, trumpet; Miles Anderson, trombone; Cecil Lytle, piano; Daryl Pratt, percussion; Dan Dunbar, percussion; David Yoken, percussion; Janos Négyesy, violin; György Négyesy, viola; Peter Farrell, cello; Peter Rofe, contrabass; Bernard Rands, conductor 3. Obbligato (1983) ................................................. (12:30) Miles Anderson, trombone; Columbia String Quartet: Benjamin Hudson, violin; Carol Zeavin, violin; Sarah Clarke, viola; Eric Bartlett, cello Total playing time: 66:14 Ê 1986, 1991 & © 1991 Composers Recordings, Inc. © 2007 Anthology of Recorded Music, Inc. Notes The practice of creating a large scale vocal composition out of progressive and composer-friendly music departments in the an “anthology” of texts by several authors, sometimes even realm of American academe. In the Fall of 1985 he became several languages, collected by a composer for that specific professor of music at Boston University. While at the purpose, is largely a phenomenon of our own times; it University of San Diego, Rands founded and conducted contrasts with the way the great song composers of past SONOR, and extraordinary new music ensemble of student centuries—above all Schubert and Wolf—tended to seize and faculty -

Five Composers Set to Coachdownload Pdf(92

Buffalo News June 3, 2012, 12:00 AM Five composers set to coach By Mary Kunz Goldman NEWS CLASSICAL MUSIC CRITIC Five composers are in residence this week at June in Buffalo, the University at Buffalo’s annual conference on avant-garde music. They will be coaching 26 students from around the world. “We not only select the Portrait of Professor David Felder in the Music Department composers based on the work Photographer: Douglas Levere that they produce, but also their abilities as a teacher,” says J.T. Rinker, the festival’s managing director. The student composers are a diverse group. “We have one from Turkey, one from Australia, a couple from Western Europe, and we have some students studying currently in the United States who originated in Asia and Europe.” The five composers are: David Felder, 58, head of UB’s music department and June in Buffalo’s creative director. A native of Cleveland, Felder studied at the University of California at San Diego with composers Bernard Rands, Roger Reynolds and Donald Erb. His compositions have been known to explore subtle gradations of pitch, and many of them are vivid, electronically enhanced soundscapes, some of them augmented by video. Robert Beaser, 58, received his master of music, M.M.A. and doctor of musical arts degrees from the Yale School of Music. He studied conducting with Otto-Werner Mueller and former BPO Music Director William Steinberg, and his composition teachers included Earle Brown, a composer associated with June in Buffalo’s early days. Beaser has been described as one of the first composers to explore the “new tonality,” a return to tonal writing as opposed to atonal and abstract music. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1990

FESTIVAL OF CONTE AUGUST 4th - 9th 1990 j:*sT?\€^ S& EDITION PETERS -&B) t*v^v- iT^^ RECENT ADDITIONS TO OUR CONTEMPORARY MUSIC CATALOGUE P66438a John Becker Concerto for Violin and Orchestra. $20.00 Violin and Piano (Edited by Gregory Fulkerson) P67233 Martin Boykan String Quartet no. 3 $40.00 (Score and Parts) (1988 Walter Hinrichsen Award) P66832 George Crumb Apparition $20.00 Elegiac Songs and Vocalises for Soprano and Amplified Piano P67261 Roger Reynolds Whispers Out of Time $35.00 String Orchestra (Score)* (1989 Pulitzer Prize) P67283 Bruce J. Taub Of the Wing of Madness $30.00 Chamber Orchestra (Score)* P67273 Chinary Ung Spiral $15.00 Vc, Pf and Perc (Score) (1989 Grawemeyer and Friedheim Award) P66532 Charles Wuorinen The Blue Bamboula $15.00 Piano Solo * Performance materials availablefrom our rental department C.F. PETERS CORPORATION ^373 Park Avenue So./New York, NY 10016/Phone (212) 686-4l47/Fax (212) 689-9412 1990 FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Oliver Knussen, Festival Coordinator by the sponsored TanglewGDd TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER Music Leon Fleisher, Artistic Director Center Gilbert Kalish, Chairman of the Faculty Lukas Foss, Composer-in-Residence Oliver Knussen, Coordinator of Contemporary Music Activities Bradley Lubman, Assistant to Oliver Knussen Richard Ortner, Administrator Barbara Logue, Assistant to Richard Ortner James E. Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Carol Wood worth, Secretary to the Faculty Harry Shapiro, Orchestra Manager Works presented at this year's Festival were prepared under the guidance of the following Tanglewood Music Center Faculty: Frank Epstein Donald MacCourt Norman Fischer John Oliver Gilbert Kalish Peter Serkin Oliver Knussen Joel Smirnoff loel Krosnick Yehudi Wyner 1990 Visiting Composer/Teachers Elliott Carter John Harbison Tod Machover Donald Martino George Perle Steven Stucky The 1990 Festival of Contemporary Music is supported by a gift from Dr. -

November 18, 2007 2646Th Concert

For the convenience of concertgoers the Garden Cafe remains open until 6:oo pm. The use of cameras or recording equipment during the performance is not allowed. Please be sure that cell phones, pagers, and other electronic devices are turned off. Please note that late entry or reentry of the East Building after 6:30 pm is not permitted. The Sixty-sixth Season of The William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin Concerts National Gallery of Art 2,646th Concert Music Department National Gallery of Art Sanctuary Sixth Street and Constitution Avenue nw by Roger Reynolds Washington, DC Steven Schick, percussionist Mailing address and 2000B South Club Drive red fish blue fish Landover, md 20785 Justin DeHart, Ross Karre, Fabio Oliveira, and Greg Stuart, percussionists Josef Kucera, Ian Saxton, and Jacob David Sudol, supporting technicians www.nga.gov November 18, 2007 Sunday Evening, 6:30 pm cover: Paul Stevenson Oles, 1971, National Gallery of Art Archives East Building Auditorium and atrium Admission free Program WORLD PREMIERE PERFORMANCE Roger Reynolds (b. 1934) Sanctuary (2007) I. Chatter/Clatter II. Oracle hi. Song Presented in honor of Let the World In: Prints by Robert Rauschenberg from the National Gallery of Art and Related Collections Original image from Sanctuary n; Ross Karre, video rendering; Karen Reynolds, image transformation; used by permission. Sanctuary has been jointly commissioned by the Contemporary Music Forum, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Randy Plostetler Living Room Fund, and the red fish blue fish percussion ensemble. Audio equipment for this concert was graciously provided by Varlc Audio of Cabin John, Maryland. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1989

I nfflfn ^(fe£k i^£to^ Wfr EDITION PETERS »8@ ^^ '^^ ^p52^ RECENT ADDITIONS TO OUR CONTEMPORARY MUSIC CATALOGUE P66905 George Crumb Gnomic Variations $20.00 Piano Solo P66965 Pastoral Drone 12.50 Organ Solo P67212 Daniel Pinkham Reeds 10.00 Oboe Solo P67097 Roger Reynolds Islands From Archipelago: I. Summer Island (Score) 16.00 Oboe and Computer-generated tape* P67191 Islands from Archipelago: II. Autumn Island 15.00 Marimba Solo P67250 Mathew Rosenblum Le Jon Ra (Score) 8.50 Two Violoncelli P67236 Bruce J. Taub Extremities II (Quintet V) (Score) 12.50 Fl, CI, Vn, Vc, Pf P66785 Charles Wuorinen Fast Fantasy (Score)+ 20.00 Violoncello and Piano P67232 Bagatelle 10.00 Piano Solo + 2 Scores neededforperformance * Performance materials availablefrom our rental department C.F. PETERS CORPORATION I 373 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016 • (212) 686-4147 J 1989 FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Oliver Knussen, Festival Coordinator 4. J* Sr* » sponsored by the TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER Leon Fleisher, Artistic Director Gilbert Kalish, Chairman of the Faculty I Lukas Foss, Composer-in-Residence Oliver Knussen, Coordinator of Contemporary Music Activities Bradley Lubman, Assistant to Oliver Knussen Richard Ortner, Administrator James E. Whitaker, Chief Coordinator Harry Shapiro, Orchestra Manager Works presented at this year's Festival were prepared under the guidance of the following Tanglewood Music Center Faculty: Frank Epstein Joel Krosnick Lukas Foss Donald MacCourt Margo Garrett Gustav Meier Dennis Helmrich Peter Serkin Gilbert Kalish Yehudi Wyner Oliver Knussen 1989 Visiting Composer/Teachers Bernard Rands Dmitri Smirnov Elena Firsova Peter Schat Tod Machover Kaija Saariaho Ralph Shapey The Tanglewood Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music and sponsored by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. -

Mizzou New Music Summer Festival

Mizzou New Music summer Festival July 11-16, 2011 ... ten world premieres, eight selected composers, four incredible performances, one extraordinary opportunity. Another World’s Rapture Remix: An Electroacoustic Chamber Recital Tuesday, July 12, 2011 • 8:00 PM • Whitmore Recital Hall Seasons with Alarm Will Sound and Susan Narucki, soprano Thursday, July 14, 2011 • 7:00 PM • Missouri Theatre Center for the Arts Mizzou’s Right to Bear New Music Friday, July 15, 2011 • 7:00 PM • Missouri Theatre Center for the Arts Eight World Premieres Saturday, July 16, 2011 • 7:00 PM •Missouri Theatre Center for the Arts We’re Blazing New Trails with the Hottest New Music… All Thanks to Your Cool Support Congratulations and many thanks to Dr. Jeanne and Rex SLAY & Sinquefield, Sinquefield Charitable Foundation and the ASSOCIATES University of Missouri – Columbia for their www.slayandassociates.com vision and commitment in bringing this festival to Missouri. 1 Mizzou New Music Summer Festival • July 11-16, 2011 Festival Schedule Monday, July 11, 2011 9:00 AM – 12:15 PM: Resident Composer Presentations Fine Arts Building Room 145 (MU Campus) - Open to the Public 1:45 PM – 3:50 PM: Resident Composer Presentations Fine Arts Building Room 145 - Open to the Public 4:00 – 5:30 PM: Alarm Will Sound Instrumentation Workshop Fine Arts Building Room 145 - Open to the Public 7:00 PM: Anna Clyne, Guest Composer Presentation Fine Arts Building Room 145 - Open to the Public 8:30 PM: Stefan Freund, MU Faculty Composer Presentation Fine Arts Building Room 145 - Open to