HOW COMPOSERS COMPOSE: in SEARCH of the QUESTIONS Page 1 of 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Approach to the Pedagogy of Beginning Music Composition: Teaching Understanding and Realization of the First Steps in Composing Music

AN APPROACH TO THE PEDAGOGY OF BEGINNING MUSIC COMPOSITION: TEACHING UNDERSTANDING AND REALIZATION OF THE FIRST STEPS IN COMPOSING MUSIC DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Vera D. Stanojevic, Graduate Diploma, Tchaikovsky Conservatory ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved By Professor Donald Harris, Adviser __________________________ Professor Patricia Flowers Adviser Professor Edward Adelson School of Music Copyright by Vera D. Stanojevic 2004 ABSTRACT Conducting a first course in music composition in a classroom setting is one of the most difficult tasks a composer/teacher faces. Such a course is much more effective when the basic elements of compositional technique are shown, as much as possible, to be universally applicable, regardless of style. When students begin to see these topics in a broader perspective and understand the roots, dynamic behaviors, and the general nature of the different elements and functions in music, they begin to treat them as open models for individual interpretation, and become much more free in dealing with them expressively. This document is not designed as a textbook, but rather as a resource for the teacher of a beginning college undergraduate course in composition. The Introduction offers some perspectives on teaching composition in the contemporary musical setting influenced by fast access to information, popular culture, and globalization. In terms of breadth, the text reflects the author’s general methodology in leading students from basic exercises in which they learn to think compositionally, to the writing of a first composition for solo instrument. -

Music Director Riccardo Muti Appoints Jessie Montgomery As Cso Mead Composer-In-Residence for 2021-24

For Immediate Release: Press Contacts: April 20, 2021 Eileen Chambers CSOA, 312-294-3092 Glenn Petry 21C Media, 212-625-2038 MUSIC DIRECTOR RICCARDO MUTI APPOINTS JESSIE MONTGOMERY AS CSO MEAD COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE FOR 2021-24 CHICAGO—The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association (CSOA) is pleased to announce the appointment of composer, violinist and educator Jessie Montgomery as its next Mead Composer-in- Residence. A winner of both the Sphinx Medal of Excellence and the ASCAP Foundation’s Leonard Bernstein Award, Montgomery has emerged as one of the most compelling and sought-after voices in new music today. Appointed by Music Director Riccardo Muti, she will begin her three-year tenure on July 1, 2021, and will continue in the role through June 30, 2024. Described as “turbulent, wildly colorful and exploding with life” (Washington Post), Montgomery’s music includes such frequently performed works as Banner (2014), Starburst (2012) and Strum (2006; rev. 2012), which have collectively been programmed almost 500 times to date, with more than 100 live and virtual performances of Starburst in the past year alone. As Mead Composer-in-Residence, she will receive commissions to write three new orchestral works for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, one to premiere during each of her three seasons in the role. In addition, she will curate MusicNOW, the CSO’s annual contemporary music series, and will receive commissions for a number of new chamber pieces to premiere in the series’ 2022-23 and 2023-24 seasons. MusicNOW will also present the Chicago premieres of some of her existing works. Founded in 1998, MusicNOW strives to bring Chicago audiences the widest possible range of today’s new music. -

How Its Styles and Techniques Changed Music Honors Thesis Lauren Felis State University of New York at New Paltz

Music of the Baroque period: how its styles and techniques changed music Item Type Thesis Authors Felis, Lauren Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States Download date 26/09/2021 16:07:48 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/1382 Running head: MUSIC OF THE BAROQUE PERIOD 1 Music of the Baroque Period: How its Styles and Techniques Changed Music Honors Thesis Lauren Felis State University of New York at New Paltz MUSIC OF THE BAROQUE PERIOD 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Abstract 3 Introduction 4 A Brief History 4 Doctrine of Affections 5 Musical Style 6 Baroque Dance 7 Baroque String Instruments 7 Baroque Composers 8 Arcangelo Corelli 9 La Folia 9 Suzuki 10 Process of Preparing Piece 10 How I Chose the Piece 10 How I prepared the Piece 11 Conclusion 11 Appendix A 14 Appendix B 15 Appendix C 16 Appendix D 17 Appendix E 18 MUSIC OF THE BAROQUE PERIOD 3 Abstract This paper explores the music of the Baroque era and how its unique traits made it diverge from the music that preceded it, as well as pave the way for music styles to come. The Baroque period, which is generally agreed to range from around 1600 to 1750, was a time of great advancement not only in arts and sciences, but in music as well. The overabundance of ornamentation sprinkled throughout the pieces composed in this era is an attribute that was uncommon in the past, and helped distinguish the Baroque style of music. -

A Practical Guide to Musical Composition Alan Belkin

1 A Practical Guide to Musical Composition by Alan Belkin [email protected] © Alan Belkin, 2008 2 Presentation The aim of this book is to discuss fundamental principles of musical composition in concise, practical terms, and to provide guidance for student composers. Many of these practical aspects of the craft of composition, especially concerning form, are not often discussed in ways useful to an apprentice composer - ways that help him to solve common problems. Thus, this will not be a "theory" text, nor an analysis treatise, but rather a guide to some of the basic tools of the trade. It is mainly based on my own experience as a composer and teacher. This book is the first in a series. The others are: Counterpoint, Orchestration, and Harmony. A complement to this book is my Workbook for Elementary Tonal Composition. For more artistic matters related to composition, please see my essay on the Musical Idea. This series is dedicated to the memory of my teacher and friend Marvin Duchow, one of the rare true scholars, a musician of immense depth and sensitivity, and a man of unsurpassed kindness and generosity. Note concerning the musical examples: Unless otherwise indicated, the musical examples are my own, and are covered by copyright. To hear the audio examples, you must use the online version of this book. To hear other examples of my music, please visit the worklist page. Scores have been reduced, and occasional detailed performance indications removed, to save space. I have also furnished examples from the standard repertoire (each marked "repertoire example"). -

UC San Diego. Center for Research in Computing and the Arts Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8h41ptz No online items UC San Diego. Center for Research in Computing and the Arts Collection Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2012 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html UC San Diego. Center for RSS 1225 1 Research in Computing and the Arts Collection Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: UC San Diego. Center for Research in Computing and the Arts Collection Identifier/Call Number: RSS 1225 Physical Description: 3.6 Linear feet(8 archives boxes and 1 card file box) Date (inclusive): 1969-2012 Abstract: The UCSD Center for Research in Computing and the Arts (CRCA) collection documents the activities of the experimental music and computer-based music research unit between 1972-1993. Admisistrative History The Project for Music Experiment, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, opened in 1972 under the direction of UCSD professor Roger Reynolds. In 1973, the project became an organized research unit at the University of California, San Diego and was re-named the Center for Music Experiment (CME). Although autonomous, the Center was monitored by an inter-departmental advisory board with UCSD Music Department faculty. The director was nominated by the board and appointed by the Chancellor for terms up to five years. The Center was designed as a performance, composition, and a technological research space for innovations with digital computer music. The Center also facilitated the Studio for Extended Performance, the Extended Vocal Techniques Ensemble (EVTE), and the KIVA Improvisation Ensemble. -

The Ethics of Orchestral Conducting

Theory of Conducting – Chapter 1 The Ethics of Orchestral Conducting In a changing culture and a society that adopts and discards values (or anti-values) with a speed similar to that of fashion as related to dressing or speech, each profession must find out the roots and principles that provide an unchanging point of reference, those principles to which we are obliged to go back again and again in order to maintain an adequate direction and, by carrying them out, allow oneself to be fulfilled. Orchestral Conducting is not an exception. For that reason, some ideas arise once and again all along this work. Since their immutability guarantees their continuance. It is known that Music, as an art of performance, causally interlinks three persons: first and closely interlocked: the composer and the performer; then, eventually, the listener. The composer and his piece of work require the performer and make him come into existence. When the performer plays the piece, that is to say when he makes it real, perceptive existence is granted and offers it to the comprehension and even gives the listener the possibility of enjoying it. The composer needs the performer so that, by executing the piece, his work means something for the listener. Therefore, the performer has no self-existence but he is performer due to the previous existence of the piece and the composer, to whom he owes to be a performer. There exist a communication process between the composer and the performer that, as all those processes involves a sender, a message and a receiver. -

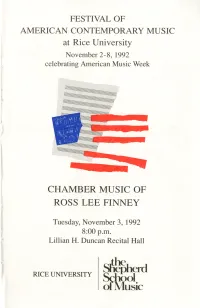

Of Music PROGRAM

FESTIVAL OF AMERICAN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC at Rice University November 2-8, 1992 celebrating American Music Week CHAMBER MUSIC OF ROSS LEE FINNEY Tuesday, November 3, 1992 8:00p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall ~herd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~l Of Music PROGRAM Sonata No. 2 in C for cello and piano (1950) Ross Lee Finney Introduction (Adagio espressivo) (b. 1906) Allegro con brio Adagio arioso Prestissimo Samuel McGill, cello John Hendrickson, piano Quartet for oboe, cello, Ross Lee Finney percussion and piano (1969) -Prologue - I. Allegro moderato - Interlude - II. Allegro capriccioso Janet Rarick, oboe Michael Dudley, cello Richard Brown, percussion John Hendrickson, piano INTERMISSION Selections from Chamber Music (1951) Ross Lee Finney (Text by James Joyce) III. At that hour when all things have repose ... VIII. Who goes amid the green wood ... XV. From dewy dreams, my soul, arise ... XVIII. 0 Sweetheart, hear you your lover's tale ... XIX. Be not sad ... XXIII. This heart that flutters near my heart ... XXV. Lightly come or lightly go ... XXX. Love came to us in time gone by .. XXXIII. Now, 0 now, in this brown land .. XXXIV. Sleep now, 0 sleep now, 0 you unquiet heart! ... XXXVI. I hear an army charging upon the land ... Jeanette Lombard, soprano Jeanne Kierman, piano Quintet for Piano and Strings (1953) Ross Lee Finney Adagio sostenuto; Allegro marcato Allegro scherzando Nocturne: Adagio sostenuto Allegro appassionato Kenneth Goldsmith, violin I Julie Savignon, violin II Csaba Erdelyi, viola Norman Fischer, cello Jeanne Kierman, piano BIOGRAPHY For more than fifty years, ROSS LEE FINNEY has been prominent both as a composer and as a teacher. -

MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction

THE COMMITTEE ON ENTERTAINMENT LAW OF THE ASSOCIATION OF THE BAR OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK January, 2003 The Committee gratefully acknowledges the contributions of prior chairpersons, Noel L. Silverman and Victoria G. Traube, and of H. Joseph Mello, the initial editor. MUSIC RIGHTS PRIMER Introduction This Primer is intended to assist lawyers who are not actively engaged in the music sub- specialty of entertainment law, but who, from time to time, may be involved with matters pertaining to that area. It is also intended for law students and non-lawyers who have an interest or involvement in the entertainment industry. We envision this Primer to be used primarily to explain the different rights that fall under the generic term “music rights”, and to delineate generally which rights are necessary for projects or product in this medium. It is not intended as a replacement for an exhaustive treatise and should not be considered a substitute for specialized legal representation required to resolve the complex issues that often arise in transactions involving music rights. Rather, it is designed to highlight issues and to provide the basic understanding of the foundations of a music project. Specialists in the field should be consulted when additional legal assistance is needed. They can easily be found in New York, Los Angeles and Nashville, and to a lesser extent, in other parts of the country. This Primer deals with music rights in the United States only. While many of the principles discussed below apply in other countries as well, there may be significant differences, and resolution of foreign issues is outside the scope of this Primer. -

Glossary for Music the Glossary for Music Includes Terms Commonly Found in Music Education and for Performance Techniques

Glossary for Music The glossary for Music includes terms commonly found in music education and for performance techniques. The intent of the glossary is to promote consistent terminology when creating curriculum and assessment documents as well as communicating with stakeholders. Ability: natural aptitude in specific skills and processes; what the student is apt to do, without formal instruction. Analog tools: category of musical instruments and tools that are non-digital (i.e., do not transfer sound in or convert sound into binary code), such as acoustic instruments, microphones, monitors, and speakers. Analyze: examine in detail the structure and context of the music. Arrangement: setting or adaptation of an existing musical composition Arranger: person who creates alternative settings or adaptations of existing music. Articulation: characteristic way in which musical tones are connected, separated, or accented; types of articulation include legato (smooth, connected tones) and staccato (short, detached tones). Artistic literacy: knowledge and understanding required to participate authentically in the arts Atonality: music in which no tonic or key center is apparent. Artistic Processes: Organizational principles of the 2014 National Core Standards for the Arts: Creating, Performing, Responding, and Connecting. Audiate: hear and comprehend sounds in one’s head (inner hearing), even when no sound is present. Audience etiquette: social behavior observed by those attending musical performances and which can vary depending upon the type of music performed. Benchmark: pre-established definition of an achievement level, designed to help measure student progress toward a goal or standard, expressed either in writing or as an example of scored student work (aka, anchor set). -

Gender and Creativity in Music Worlds • Day 1

INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM Budapest | 8-9 January 2020 MusicaFemina International Symposium is a forum for researchers, music professionals and local communities in Central and East Europe to explore relations of gender and musical practice in four interrelated programs. Gender and Creativity in Music Worlds is a two-day conference including lectures, panel discussions and roundtable discussions. The panels focus on the role of gender in music education, the relations between gender and music in the Central and East European region, and issues of gender within the music industry. At the roundtable discussions, performers, composers and managers will address issues of creativity from a gender perspective. For the first afternoon of the symposium, we invite experts from the Hungarian music world (composers, performers, journalists and music historians) to a series of roundtable discussions in order to talk about the issue of gender in the Hungarian music scene (entitled Hang-nem-váltás? / Changing Tonality?). The discussions will be followed by a special edition of Ladyfest Budapest Extra, an underground event, in Három Holló Café, with all-female bands from Germany, Poland and Hungary performing. The final event of the symposium will be the opening concert of the Transparent Sound New Music Festival, preceded by a brief discussion. Please register until 20 December, 2019 • Registration: https://forms.gle/VjykhB5qUmf1gjgd9 For further information please visit: atlatszohang.hu/musicafemina Gender and Creativity in Music Worlds • Day 1 08 JANUARY -

Comp Prog Info MM 8-11

FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC Masters of Music Composition The Florida International University MM in Music Composition Program Philosophy and Mission Statement. The MM in Composition at Florida International University is designed to assist students with the development of their own individual voices as composers while helping them to continue to develop their craft. Numerous performance opportunities of students’ works by excellent performers and ensembles as well as hands on experience in the use of new technologies including computer music, video, and interactive and notational software are an integral part of the curriculum. Many of our graduates have continued studies at other prestigious schools and have been the recipients of ASCAP and BMI Student Composition awards. The two- year MM in composition prepares composers for either continued graduate studies or as skillful composers continuing in a variety of other related occupations. For more information regarding the program contact: Dr. Orlando Jacinto Garcia, Director Music Composition Florida International University School of Music WPAC 141 University Park Miami, Florida 33199 phone (305) 348-3357; fax (305) 348-4073 email: [email protected] School of Music web page: music.fiu.edu Rev 8/11 ADMISSION AND GENERAL REQUIREMENTS (Effective fall 2011) Admission into the composition program is contingent upon the approval of the composition faculty and is dependent upon the applicant’s portfolio and previous undergraduate course work. A minimum 3.0 GPA in the student’s last 60 credits of undergraduate work is also required for admittance. Students should have a BM degree in music composition or the equivalent. After initial admission to the program, students will be required to pass history and theory placement tests and if necessary do remedial work in these areas. -

Modern Art Music Terms

Modern Art Music Terms Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Atonality: In modern music, the absence (intentional avoidance) of a tonal center. Avant Garde: (French for "at the forefront") Modern music that is on the cutting edge of innovation.. Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Form: The musical design or shape of a movement or complete work. Expressionism: A style in modern painting and music that projects the inner fear or turmoil of the artist, using abrasive colors/sounds and distortions (begun in music by Schoenberg, Webern and Berg). Impressionism: A term borrowed from 19th-century French art (Claude Monet) to loosely describe early 20th- century French music that focuses on blurred atmosphere and suggestion. Debussy "Nuages" from Trois Nocturnes (1899) Indeterminacy: (also called "Chance Music") A generic term applied to any situation where the performer is given freedom from a composer's notational prescription (when some aspect of the piece is left to chance or the choices of the performer). Metric Modulation: A technique used by Elliott Carter and others to precisely change tempo by using a note value in the original tempo as a metrical time-pivot into the new tempo. Carter String Quartet No. 5 (1995) Minimalism: An avant garde compositional approach that reiterates and slowly transforms small musical motives to create expansive and mesmerizing works. Glass Glassworks (1982); other minimalist composers are Steve Reich and John Adams. Neo-Classicism: Modern music that uses Classic gestures or forms (such as Theme and Variation Form, Rondo Form, Sonata Form, etc.) but still has modern harmonies and instrumentation.