Flame Illuminates New Way of Looking at Rivers and Lakes by Adam Hinterthuer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2009.Qxd

RisingRising toto thethe ChallengeChallenge Annual Report 2009 From the Executive Director ESA remains financially sound and programmatically strong. n spite of the difficult economic times the country is I facing, ESA remains financially sound and programmatical- ly strong. Our loyal membership stands near 10,000 and the annual meeting—this year in Albuquerque—attracted 3,599 participants with its excellent program offerings. More than 2,000 institutions worldwide subscribe to one or more of our journals, which continue to be among the most highly cited in our field. Ecology, which is 90 years old this year, was named by the Special Libraries Association (SLA) as one of the top 100 most influential journals in science and medicine in the past 100 years. ESA is engaged in a range of activities that are a testament to the breadth of interests of our members. From congressional briefings on “hot” issues to an energized blog; from specialized ESA file photo Credit: conferences and workshops to galvanizing the community behind data sharing; from the continued evo- lution of our prized diversity program to helping faculty use large scale data sets; and from the ever- increasing influence of our journals, ESA continues to be a vibrant and energized society. ESA is also looking to the future. This year, the Governing Board initiated a long range planning process that will examine the existing activities of the Society and anticipate programs and activities that may be needed in the future. We expect that many of our members will be involved in this effort and be asked to help us ensure that ESA stays relevant far into the future. -

Measuring Groundwater–Surface Water Interaction and Its Effect on Wetland Stream Benthic Productivity, Trout Lake Watershed, Northern Wisconsin, USA*

Journal of Hydrology 320 (2006) 370–384 www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol Measuring groundwater–surface water interaction and its effect on wetland stream benthic productivity, Trout Lake watershed, northern Wisconsin, USA* Randall J. Hunta,*, Mac Strandb, John F. Walkera aUS Geological Survey, 8505 Research Way, Middleton, WI 53562, USA bDepartment of Biology, Northern Michigan University, 1401 Presque Isle Avenue, Marquette, MI 49855, USA Received 10 May 2005; revised 23 May 2005 Abstract Measurements of groundwater–surface water exchange at three wetland stream sites were related to patterns in benthic productivity as part of the US Geological Survey’s Northern Temperate Lakes–Water, Energy and Biogeochemical Budgets (NTL–WEBB) project. The three sites included one high groundwater discharge (HGD) site, one weak groundwater discharge (WGD) site, and one groundwater recharge (GR) site. Large upward vertical gradients at the HGD site were associated with smallest variation in head below the stream and fewest gradient reversals between the stream and the groundwater beneath the stream, and the stream and the adjacent streambank. The WGD site had the highest number of gradient reversals reflecting the average condition being closest to zero vertical gradient. The duration of groundwater discharge events was related to the amount of discharge, where the HGD site had the longest strong-gradient durations for both horizontal and vertical groundwater flow. Strong groundwater discharge also controlled transient temperature and chemical hyporheic conditions by limiting the infiltration of surface water. Groundwater–surface water interactions were related to highly significant patterns in benthic invertebrate abundance, taxonomic richness, and periphyton respiration. The HGD site abundance was 35% greater than in the WGD site and 53% greater than the GR site; richness and periphyton respiration were also significantly greater (p%0.001, 31 and 44%, respectively) in the HGD site than in the GR site. -

The Importance of Lake-Specific Characteristics for Water Quality Across the Continental United States

The importance of lake-specific characteristics for water quality across the continental United States Read, E. K., Patil, V. P., Oliver, S. K., Hetherington, A. L., Brentrup, J. A., Zwart, J. A., ... & Weathers, K. C. (2015). The importance of lake-specific characteristics for water quality across the continental United States. Ecological Applications, 25(4), 943-955. doi:10.1890/14-0935.1.sm 10.1890/14-0935.1.sm Ecological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Ecological Applications, 25(4), 2015, pp. 943–955 Ó 2015 by the Ecological Society of America The importance of lake-specific characteristics for water quality across the continental United States 1,13 2 3 4 5 EMILY K. READ, VIJAY P. PATIL, SAMANTHA K. OLIVER, AMY L. HETHERINGTON, JENNIFER A. BRENTRUP, 6 7 8 9 10 JACOB A. ZWART, KIRSTEN M. WINTERS, JESSICA R. CORMAN, EMILY R. NODINE, R. IESTYN WOOLWAY, HILARY A. 3 11 12 3 3 3 DUGAN, ALINE JAIMES, ARIANTO B. SANTOSO, GRACE S. HONG, LUKE A. WINSLOW, PAUL C. HANSON, AND 1 KATHLEEN C. WEATHERS 1Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, New York 12545 USA 2Department of Biology and Wildlife, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775 USA 3Center for Limnology, University of Wisconsin, 680 North Park Street, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 USA 4Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853 USA 5Department of Biology, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio 45056 USA 6Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 USA -

Chapter 6 Monitoring Floodplain Restoration

Chapter 6 Monitoring Floodplain Restoration George R. Pess, Sarah A. Morley Northwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service 2725 Montlake Boulevard East, Seattle, Washington 98112, USA [email protected] Julie L. Hall, Raymond K. Timm University of Washington, School of Fishery and Aquatic Sciences Box 355020, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA [email protected] Introduction River corridors are naturally dynamic and ecologically complex components of a watershed and often contain a disproportionately high amount of the total regional biodiversity (Naiman et al. 1993; Ward et al. 2001). Unaltered river corridors have heterogeneous landscape features, dominated by dynamic conditions, and exhib- it scale-dependent biophysical patterns and processes (Ward et al. 2001). A prominent feature within river cor- ridors is the floodplain (Figure 1). Geomorphologists traditionally define a floodplain as a flat, depositional fea- ture of the river valley adjoining the river channel, formed under the present climate and hydrologic regime and during times of high discharge (Leopold et al. 1964; Dunne and Leopold 1978; Leopold 1994). Hydrologists and engineers view the floodplain either as land subject to periodic flooding or the area flooded by the 100-year flood event (Dunne and Leopold 1978). Ecologists have defined the floodplain and accompanying habitats as areas that are periodically inundated by the lateral overflow of river or lakes, or direct precipitation or ground- water; the resulting physiochemical environment causes the -

Limnology News

LIMNOLOGY NEWS News for Alumni and Friends of the Center for Limnology Fall 2018 The Year of the Flood Read more on page 6 Photo: Jeff Miller 3 Go Big Read 5 New Trout Lake Station Director 8 Hold the Salt Limnology on People’s Minds All Year Long Thanks to ‘Go Big Read’ by Adam Hinterthuer This Spring, when it was announced that Chancellor Rebecca Blank had selected Dan Egan’s book “The Death and Life of the Great Lakes” as the UW-Madison’s Go Big Read book, we knew that it was an excellent opportunity to keep limnology in the public discourse all year long. Trout Lake Station (TLS) staff hosted a book discussion for more than 40 northern Wisconsin residents at TLS. Our director Jake Vander Zanden (who Egan quotes in the book) joined Egan for a public discussion at a Madison bookstore and moderated Q & A after Egan’s official UW-Madison lecture. Our blog published posts on the Great Lakes and invasive species throughout the year. It was great to see a sustained interest in freshwater sciences, but nothing was more rewarding than watching 200 people Dan Egan answers questions from a crowd of more than 200 cram into Working Draft Beer Company for our Science on people for the CFL-sponsored “Science on Tap-Madison” event. Tap-Madison event in October. From the Director Photo: Adam Hinterthuer Egan had just finished up his week of speaking engagements Photo: Jeff Miller at the UW-Madison, including a public talk at UW Memorial Union’s Shannon Hall to more than 1,000 people Greetings! I’m excited to share recap the unprecedented the night before. -

Director's Notes Wisconsin Limnology Has Grown and Changed This Year. We Doubled the Number of Students and Postdoctoral Train

Number 18 Fall 2010 Director’s Notes practical problem‐solving thrive here. This newsletter covers a selection of the highlights Wisconsin Limnology has from 2010. grown and changed this year. We doubled the Newsletters by Email? number of students and If you would like to receive your newsletter by postdoctoral trainees. email, please send a note to Denise Karns The Hasler Laboratory is ([email protected]). chock‐full of young researchers. More CFL in the News seasoned researchers are Occasionally there is a day when a CFL scientist Steve Carpenter also doing pretty well. is not in the news, but those days are rare. This John Magnuson’s work year’s highlights include a Science Profile of on adapting to climate change is highly visible in Reinette Biggs, a feature on the CFL fleet Wisconsin. 2010 was the warmest year in featuring Dave Harring, multiple discoveries history for Lake Superior, causing the media about aquatic invasive species from Jake Vander spotlight to shine on Jim Kitchell’s studies of Zanden, an interview with Emily Stanley about how temperature affects lamprey predation on the toxic mud spill in the Danube River, and lake trout. Jake Vander Zanden, Tim Kratz and I extensive coverage of Pete McIntyre’s work on are spinning up a new project to control condition of the world’s rivers. For these and invasive smelt by manipulating lake water many more news items go to ‘CFL in the News’ temperatures. I initiated a new project to on our web page http://limnology.wisc.edu/ create alternative scenarios for the future water resources of the Yahara Watershed for 2060, Emily Stanley working with colleagues from CALS, Engineering Promoted to Full and Zoology. -

Wisconsin Groundwater Coordinating Council Minutes from Meeting Held May 7Th, 2010 Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey 3817 Mineral Point Road, Madison

Draft GCC 5/7/10 meeting minutes Draft Wisconsin Groundwater Coordinating Council Minutes from meeting held May 7th, 2010 Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey 3817 Mineral Point Road, Madison. Members Present: Todd Ambs (DNR); Kathy Pielsticker (DATCP); George Kraft (Governor’s Representative), Ken Bradbury for James Robertson (WGNHS); Chuck Warzecha for Henry Anderson (DHS); and Jim Hurley for Anders Andren (UW-System). Others Present: Emily Stanley (UW-Madison); Jim Vanden Brook and Jason Lowery (DATCP); Steve Gaffield (Montgomery Associates); Jeff Helmuth (DNR). 1) Introductions and General Business – The meeting began at 10:00 AM. The February 19th, 2010 meeting minutes were approved. 2) DNR Water Division Leadership Change – Todd Ambs reported that he would be leaving DNR and start at his new position heading up the River Network starting May 17th. The group assists local watershed groups with organizational development and substantive policy issues such as water conservation. Todd will be based in Madison but traveling much of the time. After 7 ½ years leading DNR’s Water Division Todd said he will be bring an appreciation of often under-valued public servants to his work with a wide range of advocacy groups. Todd noted that Bruce Baker will be the new Division Administrator. 3) Technical Presentation: Occurrence and Generation of Nitrite in Ground and Surface Waters in an Agricultural Watershed - Emily Stanley from UW-Madison’s Center for Limnology presented results from her recently completed UW-funded project. The talk included an explanation of the forms (nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, dissolved organic), amounts typically found in Wisconsin streams and a discussion of how the forms and amounts of N vary across a land-use gradient. -

Department of Integrative Biology

University of Wisconsin-Madison ZOOLOGY/ENVIR ST 315 – Limnology: Conservation of Aquatic Resources 2 credits https://canvas.wisc.edu/courses/118450 Course Designations and Attributes Breadth - Biological Sciences Level - Intermediate L&S Credit - Counts as Liberal Arts and Science credit in L&S Meeting Time and Location Lectures - Tuesday and Thursday, 9:55-10:45 in 132 Noland Hall Instructional Mode All face-to-face Credit Hours This class meets for two 50-minute class period each week over the fall semester and carries the expectation that students will work on course learning activities (reading, writing, problem sets, studying, etc.) for approximately 2 hours out of classroom for every class period. This syllabus includes additional information about meeting times and expectations for student work. INSTRUCTORS AND TEACHING ASSISTANTS Instructors Hilary Dugan - 226E Hasler Lab of Limnology, [email protected] Office hours: After class or by appointment Emily Stanley - 218 Hasler Lab of Limnology, [email protected] Office hours: After class or by appointment OFFICIAL COURSE DESCRIPTION Course Description General limnology: Physical, chemical and biological characteristics and processes of lakes. Environmental problems and rehabilitation of lakes. Requisites Students enrolling in this class must have taken Introductory biology (Biology/Botany/Zoology 152; Biology/Zoology 101; Biology/Biocore 301 or the equivalent). We strongly recommend taking an introductory chemistry class prior to enrollment as well (e.g., Chem103/104 or Chem 109) -

2017 Water@UW-Madison Spring Symposium – Tuesday, May 9Th

2017 Water@UW-Madison Spring Symposium – Tuesday, May 9th 2017 Speaker Time Department/Affiliation Talk Title INTRODUCTION (8:00—8:20) Steve Carpenter 8:00 Center for Limnology Steve Ackerman 8:05 Associate Vice-Chancellor of Research and Graduate Education SESSION I (8:20-9:40) Anita Thompson 8:20 Biological Systems Engineering – UW Madison Impacts of watershed land use and management on water quality Randy Lehr Northland College Adapting to climate change in Lake Superior Christy Remucal Environmental Chemistry and Technology – UW Madison An adaptive approach to remove emerging contaminants from our drinking water Bob Smail Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Historic water level variation in Wisconsin Daniel Noguera Civil and Environmental Engineering – UW Madison New ideas in biological wastewater treatment Jonathan Patz 8:50 Population Health Sciences – UW Madison Water-related health risks from climate change Tim Campbell University of Wisconsin Extension Helping Wisconsin stop aquatic hitchhikers Matt Diebel Wisconsin DNR Long-term trends in river water quality in Wisconsin Adena Rissman Forest and Wildlife Ecology – UW Madison Public support for water quality policy Bill Selbig United States Geological Survey Urban storm water research at the USGS Wisconsin Water Science Center Andrew Rypel 9:20 Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Building resilience into freshwater fisheries through ecology and management Jordan Read United States Geological Survey Changes in lake temperature and ice cover in Wisconsin Matt Ruark Soil -

SITNW 2019 Program of Presentations.Xlsx

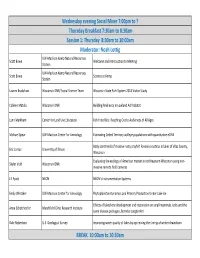

Wednesday evening Social Mixer 7:00pm to ? Thursday Breakfast 7:30am to 8:30am Session 1: Thursday 8:30am to 10:00am Moderator: Noah Lottig UW‐Madison Kemp Natural Resources Scott Bowe Welcome and Introduction to Meeting Station UW‐Madison Kemp Natural Resources Scott Bowe Science at Kemp Station Lauren Bradshaw Wisconsin DNR/ Social Science Team Wisconsin State Park System 2018 Visitor Study Colleen Matula Wisconsin DNR Building Resiliency in Lowland Ash habitat Lynn Markham Center for Land Use Education Fish Hotel Kits: Reaching Out to Audiences of All Ages Michael Spear UW‐Madison Center for Limnology Estimating Ceded Territory walleye populations with quantitative eDNA Body size trends of invasive rusty crayfish Faxonius rusticus in lakes of Vilas County, Eric Larson University of Illinois Wisconsin Evaluating the ecology of American marten in northeastern Wisconsin using non‐ Skyler Vold Wisconsin DNR invasive remote field cameras Jill Pyatt NEON NEON’s Instrumentation Systems Emily Whitaker UW‐Madison Center for Limnology Phytoplankton Dynamics and Primary Production Under Lake Ice Effects of lakeshore development and restoration on small mammals, ticks and the Anna Schotthoefer Marshfield Clinic Research Institute Lyme disease pathogen, Borrelia burgdorferi Dale Robertson U.S. Geological Survey Improving water quality of lakes by optimizing the timing of winter drawdown BREAK 10:00am to 10:30am Session 2: Thursday 10:30am to 12:00pm Moderator: Dustin Bronson A Rapid Introduction to the North Temperate Lakes Long‐Term Ecological -

SFS Presentation Grid 2016

SFS Presentation Grid 2016 Time 302303 304305 306 307 308 309310 311312 313 314 315 Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: Time/Location: [302303] – 10:30 [304305] – 10:30 [306] – 10:30 [307] – 10:30 [308] – 10:30 [309310] – 10:30 [311312] – 10:30 [313] – 10:30 [314] – 10:30 [315] – 10:30 Title: Title: Title: Title: Title: Title: Title: Title: Title: Title: CONTEMPORARY BEYOND LEVERAGING PRACTICAL LEVELS OF RESTORATION OF THE DOES COMPLIANCE FRESHWATER CADDISFLY WHAT PHYSIOLOGICAL EVALUATING WHEN AND HOW DYNAMIC THERMAL ADAPTATION RESOURCES: CITIZEN IDENTIFCATION FOR UPPER CLARK FORK WITH THE BRAZILIAN CONSERVATION IN BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH ON ION COMPENSATORY HYPORHEIC TEMPERATURE OF A PREDATOR SCIENCE OFFERS REAL LARVAE OF BAETIS RIVER, MT: FOREST CODE CENTRAL AMERICA RESPONSES TO DRYING TRANSPORT SUGGESTS MITIGATION UNDER MOSAICS INFLUENCE EXACERBATES SCIENCE AND REAL (EPHEMEROPTERA: OPPORTUNITIES FOR MITIGATE THE IMPACTS AND THE CARIBBEAN CUES IN TEMPORARY ABOUT THE POTENTIAL THE CLEAN WATER ACT: CHANNEL TEMPERATURE Sunday ECOLOGICAL DATA TO ADDRESS AND BAETIDAE) IN NORTH SYNERGY OF SUGARCANE PONDS: IMPLICATIONS TOXICITY OF SULFATE THE STATE OF THE REGIMES 10:30 CONSEQUENCES OF SOLVE REAL PROBLEMS AMERICA AGRICULTURE AND ITS Authors: FOR EFFECTS OF SCIENCE CLIMATE WARMING Authors: LEGACY ON INSTREAM Alonso Ramirez CLIMATE CHANGE Authors: Authors: Authors: Authors: H. Maurice Valett, Marc NUTRIENT Michael Griffith Authors: Katie Fogg, -

Measuring Groundwater–Surface Water Interaction and Its Effect on Wetland Stream Benthic Productivity, Trout Lake Watershed, Northern Wisconsin, USA

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2006 Measuring groundwater–surface water interaction and its effect on wetland stream benthic productivity, Trout Lake watershed, northern Wisconsin, USA Randall J. Hunt U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Mac Strand Northern Michigan University, [email protected] John F. Walker U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Hunt, Randall J.; Strand, Mac; and Walker, John F., "Measuring groundwater–surface water interaction and its effect on wetland stream benthic productivity, Trout Lake watershed, northern Wisconsin, USA" (2006). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 424. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/424 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Journal of Hydrology 320 (2006) 370–384 www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol Measuring groundwater–surface water interaction and its effect on wetland stream benthic productivity, Trout Lake watershed, northern Wisconsin, USA* Randall J. Hunta,*, Mac Strandb, John F. Walkera aUS Geological Survey, 8505 Research Way, Middleton, WI 53562, USA bDepartment of Biology, Northern Michigan University, 1401 Presque Isle Avenue, Marquette, MI 49855, USA Received 10 May 2005; revised 23 May 2005 Abstract Measurements of groundwater–surface water exchange at three wetland stream sites were related to patterns in benthic productivity as part of the US Geological Survey’s Northern Temperate Lakes–Water, Energy and Biogeochemical Budgets (NTL–WEBB) project.