Appendix 1: the Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Leonard Tilley

SIR LEONARD TILLEY JAMES HA NNAY TORONTO MORANG CO L IMITE D 1911 CONTENTS EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER ELECTED T0 THE LEGISLAT' RE CHAPTER III THE PROHIBITORY LI' ' OR LAW 29 CHAPTER VI THE MOVEMENT FOR MARITIME ' NION CONTENTS DEFEAT OF CONFEDERATION CHAPTER I' TILLEY AGAIN IN POWER CHAPTER ' THE BRITISH NORTH AMERICA ACT CHA PTER ' I THE FIRST PARLIAMENT OF CANADA CHAPTER ' II FINANCE MINISTER AND GO VERNOR INDE' CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER HE po lit ic al c aree r of Samuel Leonard Tilley did not begin until the year t hat bro ught the work of L emuel Allan Wilmot as a legislator to a we e elect ed e bers t he close . Both r m m of House of 1 850 t he l ea Assembly in , but in fol owing y r Wil elev t ed t o t he benc h t h t t he mot was a , so a province lost his services as a political refo rmer just as a new t o re t man, who was destined win as g a a reputation t he . as himself, was stepping on stage Samuel l at t he . Leonard Til ey was born Gagetown , on St 8th 1 8 1 8 i -five John River, on May , , just th rty years after the landing of his royalist grandfather at St. - l t . e John He passed away seventy eight years a r, ull t he f of years and honours , having won highest prizes that it was in the power of his native province t o bestow. -

The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864

1 Constructing Ionian Identities: The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864 Maria Paschalidi Department of History University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to University College London 2009 2 I, Maria Paschalidi, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Utilising material such as colonial correspondence, private papers, parliamentary debates and the press, this thesis examines how the Ionian Islands were defined by British politicians and how this influenced various forms of rule in the Islands between 1815 and 1864. It explores the articulation of particular forms of colonial subjectivities for the Ionian people by colonial governors and officials. This is set in the context of political reforms that occurred in Britain and the Empire during the first half of the nineteenth-century, especially in the white settler colonies, such as Canada and Australia. It reveals how British understandings of Ionian peoples led to complex negotiations of otherness, informing the development of varieties of colonial rule. Britain suggested a variety of forms of government for the Ionians ranging from authoritarian (during the governorships of T. Maitland, H. Douglas, H. Ward, J. Young, H. Storks) to representative (under Lord Nugent, and Lord Seaton), to responsible government (under W. Gladstone’s tenure in office). All these attempted solutions (over fifty years) failed to make the Ionian Islands governable for Britain. The Ionian Protectorate was a failed colonial experiment in Europe, highlighting the difficulties of governing white, Christian Europeans within a colonial framework. -

Wellingtons Peninsular War Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WELLINGTONS PENINSULAR WAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Julian Paget | 288 pages | 01 Jan 2006 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9781844152902 | English | Barnsley, United Kingdom Wellingtons Peninsular War PDF Book In spite of the reverse suffered at Corunna, the British government undertakes a new campaign in Portugal. Review: France '40 Gold 16 Jan 4. Reding was killed and his army lost 3, men for French losses of 1, Napoleon now had all the pretext that he needed, while his force, the First Corps of Observation of the Gironde with divisional general Jean-Andoche Junot in command, was prepared to march on Lisbon. VI, p. At the last moment Sir John had to turn at bay at Corunna, where Soult was decisively beaten off, and the embarkation was effected. In all, the episode remains as the bloodiest event in Spain's modern history, doubling in relative terms the Spanish Civil War ; it is open to debate among historians whether a transition from absolutism to liberalism in Spain at that moment would have been possible in the absence of war. On 5 May, Suchet besieged the vital city of Tarragona , which functioned as a port, a fortress, and a resource base that sustained the Spanish field forces in Catalonia. The move was entirely successful. Corunna While the French were victorious in battle, they were eventually defeated, as their communications and supplies were severely tested and their units were frequently isolated, harassed or overwhelmed by partisans fighting an intense guerrilla war of raids and ambushes. Further information: Lines of Torres Vedras. The war on the peninsula lasted until the Sixth Coalition defeated Napoleon in , and it is regarded as one of the first wars of national liberation and is significant for the emergence of large-scale guerrilla warfare. -

La Guerra De La Independencia: Una Visión Militar. Revista De Historia

T167-09 Port RHM Extra.fh11 9/2/10 08:50 Pgina 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K AÑO LIII Núm. EXTRA REVISTA DE HISTORIA MILITAR DE HISTORIA REVISTA 2009 Composicin NUESTRA PORTADA: Anverso del díptico correspomdiente al Ciclo de Conferencias «La Guerra de la Independencia. Una visión militar», celebrado en el Instituto de Historia y Cultura Militar durante el mes de octubre de 2008. instituto DE historia Y CULTURA MILitar Año LIII 2009 Núm. Extraordinario Los artículos y documentos de esta Revista no pueden ser traducidos ni reproducidos sin la autorización previa y escrita del Instituto de Historia y Cultura Militar. La Revista declina en los autores la total responsabilidad de sus opiniones. CATÁLOGO GENERAL DE PUBLICACIONES OFICIALES http://www.060.es Edita: NIPO: 076-09-090-7 (edición en papel) NIPO: 076-09-091-2 (edición en línea) ISSN: 0482-5748 Depósito Legal: M-7667-1958 Imprime: Imprenta del Ministerio de Defensa Tirada: 1.200 ejemplares Fecha de edición: enero, 2010 NORMAS PARA LA PUBLICACIÓN DE ORIGINALES La Revista de Historia Militar es una publicación del Instituto de Historia y Cultura Militar. Su periodicidad es semestral y su volumen, generalmente, de doscientas ochenta y ocho páginas. Puede colaborar en ella todo escritor, militar o civil, español o extranjero, que se interese por los temas históricos relacionados con la institución militar y la profesión de las armas. En sus páginas encontrarán acogida los trabajos que versen sobre el pensamiento militar a lo largo de la historia, deontología y orgánica militar, instituciones, acontecimientos bélicos, personalidades militares destacadas y usos y costumbres del pasado, particularmente si contienen enseñanzas o antecedentes provechosos para el militar de hoy, el estudioso de la historia y jóvenes investigadores. -

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Dickson Nick Lipscombe Msc, Frhists

“Wellington’s Gunner in the Peninsula” – Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Dickson Nick Lipscombe MSc, FRHistS INTRODUCTION Wellington was, without doubt, a brilliant field commander but his leadership style was abrupt and occasionally uncompromising. He despised gratuitous advice and selected his close personal staff accordingly. He trained his infantry generals as divisional commanders but not army commanders; of his cavalry commanders he had little time often pouring scorn on their inability to control their units and formations in battle; but it was his artillery commanders that he kept at arm’s-length, suspicious of their different chain of higher command and, in consequence, their motives. One gunner officer was to break through this barrier of distrust, he was a mere captain but by the end of the war he was to become the commander of all the allied artillery succeeding to what was properly a major general’s command. EARLY LIFE 1777-1793 Alexander Dickson was born on the 3rd June 1777, the third son of Admiral William Dickson and Jane Collingwood of Sydenham House, Roxburghshire. There is little information regarding his childhood and it is difficult to paint an accurate picture from his marvellous diaries, or the ‘Dickson Manuscripts’1 as they are known. By the time Dickson commences his peninsular diaries, at the age of 32 and in his 15th year of army service, both his parents and two of his older brothers had died. His mother was to die when he was only five, and as the young Dickson was coming to terms with this tragedy his oldest brother James also died, aged just fifteen. -

Fremantle Prison Australian History Curriculum Links

AUSTRALIAN HISTORY CURRICULUM @ FREMANTLE PRISON LINKS FOR YEAR 9 FREMANTLE PRISON AUSTRALIAN HISTORY CURRICULUM LINKS FOR YEAR 9 THE MAKING OF THE MODERN WORLD – MOVEMENT OF PEOPLES 1 AUSTRALIAN HISTORY CURRICULUM @ FREMANTLE PRISON LINKS FOR YEAR 9 CONTENTS Fremantle Prison 3 Curriculum Links 4 Historical Inquiry 6 Planning a School Excursion 8 Suggested Pre‐Visit Activity 11 Suggested Post‐Visit Activity 13 Historical Overview – Convict and Colonial Era 14 2 AUSTRALIAN HISTORY CURRICULUM @ FREMANTLE PRISON LINKS FOR YEAR 9 FREMANTLE PRISON In 2010 Fremantle Prison, along with 10 other historic convict sites around Australia, was placed on the World Heritage Register for places of universal significance. Collectively known as the Australian Convict Sites these places tell the story of the colonisation of Australia and the building of a nation. Fremantle Prison is Western Australia’s most important historical site. As a World Heritage Site, Fremantle Prison is recognised as having the same level of cultural significance as other iconic sites such as the Pyramids of Egypt, the Great Wall of China, or the Historic Centre of Rome. For 136 years between 1855 and 1991 Fremantle Prison was continuously occupied by prisoners. Convicts built the Prison between 1851 and 1859. Initially called the Convict Establishment, Fremantle Prison held male prisoners of the British Government transported to Western Australia. After 1886 Fremantle Prison became the colony’s main place of incarceration for men, women and juveniles. Fremantle Prison itself was finally decommissioned in November 1991 when its male prisoners were transferred to the new maximum security prison at Casuarina. Fremantle Prison was a brutal place of violent punishments such as floggings and hangings. -

The Education of a Field Marshal :: Wellington in India and Iberia

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1992 The education of a field am rshal :: Wellington in India and Iberia/ David G. Cotter University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Cotter, David G., "The ducae tion of a field marshal :: Wellington in India and Iberia/" (1992). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1417. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1417 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EDUCATION OF A FIELD MARSHAL WELLINGTON IN INDIA AND IBERIA A Thesis Presented by DAVID' G. COTTER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1992 Department of History Copyright by David G. Cotter 1992 All Rights Reserved ' THE EDUCATION OF A FIELD MARSHAL WELLINGTON IN INDIA AND IBERIA A Thesis Presented by DAVID G. COTTER Approved as to style and content by Franklin B. Wickwire, Chair )1 Mary B/ Wickwire 'Mary /5. Wilson Robert E. Jones^ Department Chai^r, History ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to all in the History department at the University of Massachusetts, especially Professors Stephen Pelz, Marvin Swartz, R. Dean Ware, Mary Wickwire and Mary Wilson. I am particularly indebted to Professor Franklin Wickwire. He performed as instructor, editor, devil's advocate, mentor and friend. -

Waterloo 200

WATERLOO 200 THE OFFICIAL SOUVENIR PUBLICATION FOR THE BICENTENARY COMMEMORATIONS Edited by Robert McCall With an introduction by Major General Sir Evelyn Webb-Carter KCVO OBE DL £6.951 TheThe 200th Battle Anniversary of Issue Waterloo Date: 8th May 2015 The Battle of Waterloo The Isle of Man Post Offi ce is pleased 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man to celebrate this most signifi cant historical landmark MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 in collaboration with 75p 75p Waterloo 200. Isle of Man Isle of Man MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 SET OF 8 STAMPS MINT 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH31 – £6.60 PRESENTATION PACK TH41 – £7.35 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FIRST DAY COVER 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH91 – £7.30 SHEET SET MINT TH66 – £26.40 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FOLDER “The whole art of war consists of guessing at what is on the other side of the hill” TH43 – £30.00 Field Marshal His Grace The Duke of Wellington View the full collection on our website: www. iomstamps.com Isle of Man Stamps & Coins GUARANTEE OF SATISFACTION - If you are not 100% PO Box 10M, IOM Post Offi ce satisfi ed with the product, you can return items for exchange Douglas, Isle of Man IM99 1PB or a complete refund up to 30 days from the date of invoice. -

“Incorrigible Rogues”: the Brutalisation of British Soldiers in the Peninsular War, 1808-1814

BRUTALISATION OF BRITISH SOLDIERS IN THE PENINSULAR WAR “Incorrigible Rogues”: The Brutalisation of British Soldiers in the Peninsular War, 1808-1814 ALICE PARKER University of Liverpool Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This article looks at the behaviour of the British soldiers in the Peninsular War between 1808 and 1814. Despite being allies to Spain and Portugal, the British soldiers committed violent acts towards civilians on a regular basis. Traditionally it has been argued that the redcoat’s misbehaviour was a product of their criminal backgrounds. This article will challenge this assumption and place the soldiers’ behaviour in the context of their wartime experience. It will discuss the effects of war upon soldiers’ mentality, and reflect upon the importance of psychological support in any theatre of war. In 2013 the UK Ministry of Justice removed 309 penal laws from the statute book, one of these being the Vagrancy Act of 1824.1 This Act was introduced for the punishment of ‘incorrigible rogues’ and was directed at soldiers who returned from the Napoleonic Wars and had become ‘idle and disorderly…rogues and vagabonds’.2 Many veterans found it difficult to reintegrate into British society after experiencing the horrors of war at time when the effects of combat stress were not recognised.3 The need for the Act perhaps underlines the degrading effects of warfare upon the individual. The behaviour of British soldiers during the Peninsular War was far from noble and stands in stark contrast to the heroic image propagated in contemporary -

Casanova, Julían, the Spanish Republic and Civil

This page intentionally left blank The Spanish Republic and Civil War The Spanish Civil War has gone down in history for the horrific violence that it generated. The climate of euphoria and hope that greeted the over- throw of the Spanish monarchy was utterly transformed just five years later by a cruel and destructive civil war. Here, Julián Casanova, one of Spain’s leading historians, offers a magisterial new account of this crit- ical period in Spanish history. He exposes the ways in which the Republic brought into the open simmering tensions between Catholics and hard- line anticlericalists, bosses and workers, Church and State, order and revolution. In 1936, these conflicts tipped over into the sacas, paseos and mass killings that are still passionately debated today. The book also explores the decisive role of the international instability of the 1930s in the duration and outcome of the conflict. Franco’s victory was in the end a victory for Hitler and Mussolini, and for dictatorship over democracy. julián casanova is Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Zaragoza, Spain. He is one of the leading experts on the Second Republic and the Spanish Civil War and has published widely in Spanish and in English. The Spanish Republic and Civil War Julián Casanova Translated by Martin Douch CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521493888 © Julián Casanova 2010 This publication is in copyright. -

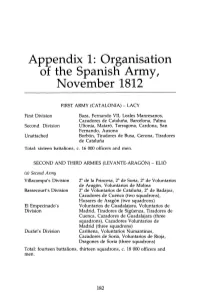

Appendix 1: Organisation of the Spanisn Army, November 1812

Appendix 1: Organisation of the Spanisn Army, November 1812 FIRST ARMY (CATALONlA) - LACY First Division Baza, Fernando VII, Leales Manresanos, Cazadores de Catalufla, Barcelona, Palma Second Division Ultonia, Matar6, Tarragona, Cardona, San Fernando, Ausona Unattached Borb6n, Tiradores de Busa, Gerona, Tiradores de Catalufla Total: sixteen battalions, c. 16 000 officers and men. SECOND AND THIRD ARMIES (LEV ANTE-ARAGON) - EUO (a) Second Army Villacampa' s Division 2° de la Princesa, 2° de Soria, 2° de Voluntarios de Arag6n, Voluntarios de Molina Bassecourt' s Division 2° de Voluntarios de Catalufla, 2° de Badajoz, Cazadores de Cuenca (two squadrons), Husares de Arag6n (two squadrons) EI Empecinado' s Voluntarios de Guadalajara, Voluntarios de Division Madrid, Tiradores de Sigüenza, Tiradores de Cuenca, Cazadores de Guadalajara (three squadrons), Cazadores Voluntarios de Madrid (three squadrons) Duran' s Division Cariflena, Voluntarios Numantinos, Cazadores de Soria, Voluntarios de Rioja, Dragones de Soria (three squadrons) Total: fourteen battalions, thirteen squadrons, c. 18 000 officers and men. 182 Appendix 1 183 (h) Third Army Vanguard - Freyre 1er de Voluntarios de la Corona, 1er de Guadix, Velez Malaga, Carabinieros Reales (one squadron), 1er Provisional de Linea (three squadrons), 2° Provisional de Linea (three squadrons), 1er Provisional de Dragones, (three squadrons), 2° Provisional de Dragones (three squadrons), 1er Provisional de Husares (two squadrons) Roche' s Division Voluntarios de Alicante, Canarias, Chinchilla, Cazadores de Valencia, Husares de Fernando VII (three squadrons) Montijo's Brigade 2° de Guardias Walonas, 1er de Badajoz, Cuenca Michelena' s Brigade 1er de Voluntarios de Arag6n, Tiradores de Cadiz, 2° de Mallorca Mijares' Brigade 1"' de Burgos, Alcazar de San Juan, BaHen, Lorca, Voluntarios de Jaen U na ttachedl garrisons Almansa, America, Alpujarras, Almeria, Cazadores de Jaen (one squadron), Cazadores de la Mancha (two squadrons) Total: twenty-two battalions, twenty-one squadrons, c. -

Wellington's Two-Front War: the Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Wellington's Two-Front War: The Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L. Moon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WELLINGTON’S TWO-FRONT WAR: THE PENINSULAR CAMPAIGNS, 1808 - 1814 By JOSHUA L. MOON A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Joshua L. Moon defended on 7 April 2005. __________________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ______________________________ Edward Wynot Committee Member ______________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named Committee members ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS No one can write a dissertation alone and I would like to thank a great many people who have made this possible. Foremost, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Donald D. Horward. Not only has he tirelessly directed my studies, but also throughout this process he has inculcated a love for Napoleonic History in me that will last a lifetime. A consummate scholar and teacher, his presence dominates the field. I am immensely proud to have his name on this work and I owe an immeasurable amount of gratitude to him and the Institute of Napoleon and French Revolution at Florida State University.