The Migration of the White Stork in Egypt and Adjacent Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharaonic Egypt Through the Eyes of a European Traveller and Collector

Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot Esther de Groot s0901245 Book and Digital Media Studies University of Leiden First Reader: P.G. Hoftijzer Second reader: R.J. Demarée 0 1 2 Pharaonic Egypt through the eyes of a European traveller and collector Excerpts from the travel diary of Johann Michael Wansleben (1672-3), with an introduction and annotations by Esther de Groot. 3 4 For Harold M. Hays 1965-2013 Who taught me how to read hieroglyphs 5 6 Contents List of illustrations p. 8 Introduction p. 9 Editorial note p. 11 Johann Michael Wansleben: A traveller of his time p. 12 Egypt in the Ottoman Empire p. 21 The journal p. 28 Travelled places p. 53 Acknowledgments p. 67 Bibliography p. 68 Appendix p. 73 7 List of illustrations Figure 1. Giza, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 104 p. 54 Figure 2. The pillar of Marcus Aurelius, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 123 p. 59 Figure 3. Satellite view of Der Abu Hennis and Der el Bersha p. 60 Figure 4. Map of Der Abu Hennis from the original manuscript p. 61 Figure 5. Map of the visited places in Egypt p. 65 Figure 6. Map of the visited places in the Faiyum p. 66 Figure 7. An offering table from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 39 p. 73 Figure 8. A stela from Saqqara, BNF Ms. Italien 435, folio 40 p. 74 Figure 9. -

Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future

Economy Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi With the Egyptian children around him, when he gave go ahead to implement the East Port Said project On November 27, 2015, President Ab- Egyptians’ will to successfully address del-Fattah el-Sissi inaugurated the initial the challenges of careful planning and phase of the East Port Said project. This speedy implementation of massive in- was part of a strategy initiated by the vestment projects, in spite of the state of digging of the New Suez Canal (NSC), instability and turmoil imposed on the already completed within one year on Middle East and North Africa and the August 6, 2015. This was followed by unrelenting attempts by certain interna- steps to dig out a 9-km-long branch tional and regional powers to destabilize channel East of Port-Said from among Egypt. dozens of projects for the development In a suggestive gesture by President el of the Suez Canal zone. -Sissi, as he was giving a go-ahead to This project is the main pillar of in- launch the new phase of the East Port vestment, on which Egypt pins hopes to Said project, he insisted to have around yield returns to address public budget him on the podium a galaxy of Egypt’s deficit, reduce unemployment and in- children, including siblings of martyrs, crease growth rate. This would positively signifying Egypt’s recognition of the role reflect on the improvement of the stan- of young generations in building its fu- dard of living for various social groups in ture. -

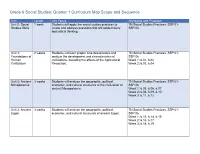

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

Bio-Climatic Analysis and Thermal Performance of Upper Egypt “A

ESL-IC-12-10-48 Bio-Climatic Analysis and Thermal Performance of Upper Egypt “A Case Study Kharga Region” Mervat Hassan Khalil Housing & Building National Research Center, Cairo, Egypt, P. Box 1770 E. mail: marvat.hassan.khalil@gmail .com ABSTRACT As a result of the change and development of Egyptian society, Egyptian government has focused its attention of comprehensive development to various directions. One of these attentions is housing, construction and land reclamation in desert and Upper Egypt. In the recent century the most attentions of the government is the creation of new wadi parallel to Nile wadi in the west desert. Kharga Oasis is 25°26′56″North latitude and 30°32′24″East longitude. This oasis, is the largest of the oases in the westren desert of Egypt. It required the capital of the new wadi (Al Wadi Al Gadeed Government). The climate of this oasis is caricaturized by; aridity, high summer daytime temperature, large diurnal temperature variation, low relative humidity and high solar radiation. In such conditions, man losses his ability to work and to contribute effectively in the development planning due to the high thermal stress affected on him. In designing and planning in this region, it is necessary not only to understand the needs of the people but to create an indoor environment which is suitable for healthy, pleasant, and comfortable to live and work in it. So, efforts have been motivated towards the development of new concepts for building design and urban planning to moderate the rate, direction and magnitudes of heat flow. Also, reduce or if possible eliminate the energy expenditure for environmental control. -

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010

Country Advice Egypt Egypt – EGY37024 – Treatment of Anglican Christians in Al Minya 2 August 2010 1. Please provide detailed information on Al Minya, including its location, its history and its religious background. Please focus on the Christian population of Al Minya and provide information on what Christian denominations are in Al Minya, including the Anglican Church and the United Coptic Church; the main places of Christian worship in Al Minya; and any conflict in Al Minya between Christians and the authorities. 1 Al Minya (also known as El Minya or El Menya) is known as the „Bride of Upper Egypt‟ due to its location on at the border of Upper and Lower Egypt. It is the capital city of the Minya governorate in the Nile River valley of Upper Egypt and is located about 225km south of Cairo to which it is linked by rail. The city has a television station and a university and is a centre for the manufacture of soap, perfume and sugar processing. There is also an ancient town named Menat Khufu in the area which was the ancestral home of the pharaohs of the 4th dynasty. 2 1 „Cities in Egypt‟ (undated), travelguide2egypt.com website http://www.travelguide2egypt.com/c1_cities.php – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 1. 2 „Travel & Geography: Al-Minya‟ 2010, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2 August http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/384682/al-Minya – Accessed 28 July 2010 – Attachment 2; „El Minya‟ (undated), touregypt.net website http://www.touregypt.net/elminyatop.htm – Accessed 26 July 2010 – Page 1 of 18 According to several websites, the Minya governorate is one of the most highly populated governorates of Upper Egypt. -

Women's Position and Attitudes Towards Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Van Rossem et al. BMC Public Health (2015) 15:874 DOI 10.1186/s12889-015-2203-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Women's position and attitudes towards female genital mutilation in Egypt: A secondary analysis of the Egypt demographic and health surveys, 1995-2014 Ronan Van Rossem1*, Dominique Meekers2 and Anastasia J. Gage2 Abstract Background: Female genital mutilation (FGM) is still widespread in Egyptian society. It is strongly entrenched in local tradition and culture and has a strong link to the position of women. To eradicate the practice a major attitudinal change is a required for which an improvement in the social position of women is a prerequisite. This study examines the relationship between Egyptian women’s social positions and their attitudes towards FGM, and investigates whether the spread of anti-FGM attitudes is related to the observed improvements in the position of women over time. Methods: Changes in attitudes towards FGM are tracked using data from the Egypt Demographic and Health Surveys from 1995 to 2014. Multilevel logistic regressions are used to estimate 1) the effects of indicators of a woman’ssocial position on her attitude towards FGM, and 2) whether these effects change over time. Results: Literate, better educated and employed women are more likely to oppose FGM. Initially growing opposition to FGM was related to the expansion of women’s education, but lately opposition to FGM also seems to have spread to other segments of Egyptian society. -

In Wadi Allaqi, Egypt

ENVIRONMENTAL VALUATION AND MANAGEMENT OF PLANTS IN WADI ALLAQI, EGYPT FINAL REPORT IDRC OQ w W1.44 Trent University AUGUST 1998 ENVIRONMENTAL VALUATION AND-MANAGEMENT OF PLANTS IN WADI ALLAQI, EGYPT Final report Editors: Belal, A.E. , B. Leith, J. Solway and 1. Springuel Submitted To INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH CENTRE (IDRC) CANADA File: 95-100"1/02 127-01 UNIT OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES AND DEVELOPMENT, SOUTH VALLEY UNIVERSITY, ASWAN, EGYPT A-RC hf v 5 91, 5 7 By Acknowledgements The Project team of both South Valley and Trent Universities wish to thank the International Development Research Center (IDRC) Ottawa, Canada, for supporting the project with funding and for visiting the site. We also thank the staff of the IDRC Cairo Office for their assistance. This report is based upon the knowledge, hard work, and support of many people and institutions. We thank the British Council for the support they have provided in training many members of the team and UNESCO for providing support for the Allaqi project and Biosphere Reserve. We appreciate the good working relationship that we have developed with the Egyptian Environment Affairs Agency. Dr. M. Kassas of Cairo University has provided valuable intellectual direction for the project. We thank C. Fararldi who has assisted the project in numerous ways and Gordon Dickinson for writing notes on establishing the visitor center in Wadi Allaqi We wish to thank the research offices of Trent University and South Valley University. We are deeply grateful to the residents of Wadi Allaqi for their help and continued support and patience towards our project. -

Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2)

Name: Period: Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2) Definition Example Sentence Symbol/Picture Nile River: Main water source for ancient Egypt, flows south to north, emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. Flooding of this river brought rich silt (soil) to the Nile River Valley for farming. Cataracts: Wild and difficult to navigate rapids that choke the Nile River through southern Egypt. Made travel difficult. Delta: A triangle shaped formation at the mouth of a river, created by deposit of sediment. Often fan shaped with smaller rivers splitting up and flowing into the larger body of water. Sahara Desert: The largest desert in the world, located to the west of Ancient Egypt. Name: Period: Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2) Definition Example Sentence Symbol/Picture Kemet: Means “black land.” The Egyptians called their lanf Kemet because of the the dark, fertile mud (silt) left behind by the Nile’s annual floods. Shaduf: Irrigation device invented in Egypt-a bucket attached to a long pole to dip into the river. Still used by egyptian farmers today. Upper Egypt: The southern area of Egypt, where the city of Thebes and the Valley of the Kings are located. Called “Upper Egypt” because of higher elevation. Lower Egypt: The northern area of Egypt, where the Nile River delta, the Great Pyramids at Giza and the city of Cairo are located. Called “Lower Egypt” because of lower elevation. Name: Period: Egypt: Vocabulary Terms (2) Definition Example Sentence Symbol/Picture Memphis: Capital city of the Old Kingdom, located in Lower Egypt, founded by Pharaoh Menes. Strategically located as a link between Upper and Lower Egypt. -

Abu Simbel Solar Alignment 1

Abu Simbel Solar Alignment 1 Abu Simbel was built by Pharaoh Rameses II between 1279 and 1213 B.C to celebrate his domination of Nubia, and his piety to the gods, principally Amun-Re, Ra- Horakhty and Ptah, as well as his own deification. It is located 250 kilometers southeast of the city of Aswan. The original temple was positioned on the bank of the Nile, but it was raised up 300 meters by an international relocation project supported by UNESDO. This mammoth engineering effort was undertaken between 1964 and 1968 to prevent the flooding of the temple by the rising waters of Lake Nasser caused by the new Aswan High Dam. The satellite photo above, and on the next page, shows the entrance walkway ramp, and the area on the face of the cliff where the four giant statues of Ramses II are positioned. The interior of the temple extends to the left of the statuary and is hidden beneath the huge man-made berm to the left of the photograph. The 'Visitor Center' buildings can be seen as the three squares near the left-hand edge of the photo. The horizontal line in the upper right corner represents a distance of 50 meters, and the circle indicates the major compass directions clockwise from the top (north) as east, south and west. The interior of the temple is inside the sandstone cliff in the form of a man- made cave cut out of the rock. It consists of a series of halls and rooms extending back a total of 56 meters (185 feet) from the entrance. -

The Secrets of Egypt & the Nile

the secrets of egypt & the nile 2021 - 2022 Dear Valued Guest, Egypt has captured the world’s imagination and continues to make an extraordinary impression on those who visit; and beginning in September 2021, we are delighted to take you there. While traveling along Egypt’s Nile River, you’ll be treated to a connoisseur’s discovery of this ancient civilization as only AmaWaterways can provide—with an unparalleled river cruise and land adventure that includes exquisite cuisine, beautiful accommodations, authentic excursions and extraordinary service. Your journey along the world’s longest river on board our spectacular, newly designed AmaDahlia will take you to some of Egypt’s most iconic sites. Discover ancient splendors such as the Great Hypostyle Hall of Karnak, the beguiling Temple of Luxor and the mystifying Valley of the Kings and Queens, along with exclusive access to the Tomb of Queen Nefertari. While in Cairo, you’ll stay at the 5-star Four Seasons at The First Residence, an oasis in the middle of the city, where each day, you’ll experience some of the world’s most astonishing antiquities. Come face to face with King Tut’s priceless discoveries at the Egyptian Museum, as well as the Great Sphinx and the three Pyramids of Giza, the last surviving of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; and gain private access to Cairo’s Abdeen Presidential Palace. This mesmerizing destination has entranced archaeologists and historians for generations and inspired its own field of study—Egyptology. Now it’s time for you to be entranced. We look forward to sharing Egypt with you. -

Public Weather and Media in Egypt

Public weather and media in Egypt Dr. Aly kotb The Egyptian Meteorological Authority Koubry El-Quobba /Cairo/Egypt Tel. (+002) 01005825753 E-mail: [email protected] The geographical location of Egypt makes affected by different phenomenon and air mass….. 1. 1 Geographical location Egypt is located in the sub-tropical climatic zone between latitudes 22°N and 32°N. It is surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the red Sea to the east, the great African desert to the west and the tropical zone to the south in upper Egypt. Most of Egyptian Areas lands are flat except the North East (southern part of Sinai) and the areas adjacent to the Red Sea which are rather mountainous areas with peaks reaching approximately three kilometres. 1. 2 Main climatic characteristics Due to its location in the subtropical zone between the middle latitude climate zone to the north and the tropical climate zone to the south, Egypt is exposed to varying weather regimes. In the warm season (which extends from late spring to mid autumn) the tropical weather dominates. In the cold season (which extends from mid autumn to late spring) the middle latitudes weather prevails. El-Fandy (1946) and Zohdy (1971) show that during the cold season the northern part of Egypt is affected by the sporadic passage of upper westerly troughs associated with Mediterranean depression moving from west to east. Some of these depressions when reaching the east Mediterranean deepen and become stationary providing the northern part of Egypt with 1 cold winds and sometimes very heavy rain.