PHJV Implementation Plan Prairie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas

A NATURE ALBERTA CHECKLIST IMPORTANT AND BIRD BIODIVERSITY AREAS IMPORTANT BIRD OF ALBERTA AND BIODIVERSITY AREAS OF ALBERTA NATURE ALBERTA NATURE Use this Checklist as your guide to explore and discover the fascinating natural history and biodiversity of our province. naturealberta.ca A COMMUNITY CONNECTED BY A LOVE OF NATURE The year was 1970. Six nature clubs came together to form the Federation of Alberta Naturalists. More than four decades later, and now known as Nature Alberta, we are grateful for the clubs, the people and the history that has enabled this organization to become the voice for the greater appreciation and conservation of Alberta’s natural environment. We strive to connect Albertans with the natural world that exists all around us. By encouraging Albertans to learn more about and understand natural history and ecological processes, we help ensure that Alberta’s natural heritage and its biodiversity is widely enjoyed, deeply appreciated and thoroughly protected. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Nature Alberta gratefully acknowledges the many individuals and organizations who have contributed to this project. Special thanks to Rob Worona and Margot Hervieux for contributing their time and expertise to reviewing and editing this publication. Thank you also to all of the volunteer IBA Caretakers, past, present and future, who commit to monitoring and stewarding these important natural areas. This project would also not have been possible without the generous support of our partners, including TD Friends of the Environment and Alberta Conservation Association. Cover photo: Yellow-rumped Warbler, D. Godkin Copyright ©2019 Nature Alberta. All rights reserved. SOURCES Information contained within this Checklist has been compiled from the following and other sources as annotated within the publication: BirdLife IBA Important Bird Area Alberta Guide booklet ©2014 Nature Alberta Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas in Canada https://www.ibacanada.org/ Bird Life International website and Data Zone http://www.birdlife.org/ Blue-winged Teal Photo: G. -

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

The Camper's Guide to Alberta Parks

Discover Value Protect Enjoy The Camper’s Guide to Alberta Parks Front Photo: Lesser Slave Lake Provincial Park Back Photo: Aspen Beach Provincial Park Printed 2016 ISBN: 978–1–4601–2459–8 Welcome to the Camper’s Guide to Alberta’s Provincial Campgrounds Explore Alberta Provincial Parks and Recreation Areas Legend In this Guide we have included almost 200 automobile accessible campgrounds located Whether you like mountain biking, bird watching, sailing, relaxing on the beach or sitting in Alberta’s provincial parks and recreation areas. Many more details about these around the campfire, Alberta Parks have a variety of facilities and an infinite supply of Provincial Park campgrounds, as well as group camping, comfort camping and backcountry camping, memory making moments for you. It’s your choice – sweeping mountain vistas, clear Provincial Recreation Area can be found at albertaparks.ca. northern lakes, sunny prairie grasslands, cool shady parklands or swift rivers flowing through the boreal forest. Try a park you haven’t visited yet, or spend a week exploring Activities Amenities Our Vision: Alberta’s parks inspire people to discover, value, protect and enjoy the several parks in a region you’ve been wanting to learn about. Baseball Amphitheatre natural world and the benefits it provides for current and future generations. Beach Boat Launch Good Camping Neighbours Since the 1930s visitors have enjoyed Alberta’s provincial parks for picnicking, beach Camping Boat Rental and water fun, hiking, skiing and many other outdoor activities. Alberta Parks has 476 Part of the camping experience can be meeting new folks in your camping loop. -

Regional Lakes Perspective Oldman River Region 1

GOVDC CA3 AL Lsthoriar^a^Ar.a t< OMR 9 1975 04 2 REGIONAL LAKES PERSPECTIVE OLDMAN RIVER REGION i?rJ 1. INVENTORY OLDMAN RIVER REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION 1975 J GOVDC CA3 AL OMR 9 197 5 042 Oldman River Regional Planning Commission Oldman River region : regional lakes perspective. 1. Inventory 35057007687147 OLDMAN RIVER REGION REGIONAL LAKES PERSPECTIVE 1. INVENTORY Project Co-ordinator: John L. Kovacs, Associate Planner Report & Research: Lynda Paterson, Research Officer Michael Luco, Research Officer Published by OLDMAN RIVER REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION October, 1975 FOREWORD In December, 1974, the Preliminary Regional Plan for the Oldman River Region was approved by the Provincial Planning Board. The Plan con tains guidelines and policies for the development and betterment of the Oldman River Region. Among other things, the Plan established that a com prehensive plan for outdoor recreation and open space facilities is required for the Region and that such a plan should be consistent with municipal, provincial and federal objectives. This report entitled, Oldman River Region — Regional Lakes Perspective 1. Inventory is the first stage of an evolving regional plan for out door recreation and open space. It contains a summary of relevant data nec essary for management planning of our region's lake resources. This inventory was made possible through assistance provided by the Land Use Forum's Technical Committee on Lakes and Lake Shorelands and methodologies developed by its participating agencies. This inventory on lakes also forms part of the survey phase of the Southern Alberta Recreation Enhancement Study set up through Alberta Environment to assess and enhance water based recreation in Southern Alberta. -

RURAL ECONOMY Ciecnmiiuationofsiishiaig Activity Uthern All

RURAL ECONOMY ciEcnmiIuationofsIishiaig Activity uthern All W Adamowicz, P. BoxaIl, D. Watson and T PLtcrs I I Project Report 92-01 PROJECT REPORT Departmnt of Rural [conom F It R \ ,r u1tur o A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta W. Adamowicz, P. Boxall, D. Watson and T. Peters Project Report 92-01 The authors are Associate Professor, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton; Forest Economist, Forestry Canada, Edmonton; Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton and Research Associate, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta, Edmonton. A Socio-Economic Evaluation of Sportsfishing Activity in Southern Alberta Interim Project Report INTROI)UCTION Recreational fishing is one of the most important recreational activities in Alberta. The report on Sports Fishing in Alberta, 1985, states that over 340,000 angling licences were purchased in the province and the total population of anglers exceeded 430,000. Approximately 5.4 million angler days were spent in Alberta and over $130 million was spent on fishing related activities. Clearly, sportsfishing is an important recreational activity and the fishery resource is the source of significant social benefits. A National Angler Survey is conducted every five years. However, the results of this survey are broad and aggregate in nature insofar that they do not address issues about specific sites. It is the purpose of this study to examine in detail the characteristics of anglers, and angling site choices, in the Southern region of Alberta. Fish and Wildlife agencies have collected considerable amounts of bio-physical information on fish habitat, water quality, biology and ecology. -

Attachment 2 Sample Plan, Profiles and Books of Reference

NOVA Gas Transmission Ltd. Edson Mainline Expansion Project Sample Notices and Plan, Project and Book of Reference Attachment 2 Attachment 2 Sample Plan, Profiles and Books of Reference TRAPPERTRAPPER TRAPPER T R 2T 2 R 6 9 2 2 6 9 12 -, BINGLEY -,11 CRIMSON LAKE -,22 Ü ST756 11 NORTH -, SASKATCHEWAN -,11 RIVER ORAS ST598 ROCKY FERRIER MOUNTAIN HOUSE 11A-, GARTH ALHAMBRA -,11 RAM RIVER ST752 -,22 STRACHAN 752 ST DOVERCOURT Edson ML Loop No. 4 (Alford Creek Section) O'CHIESE CEMETERY 203A PRAIRIE Legend CREEK BUTTE Edson ML Loop No. 4 - Alford Creek Section CHEDDERVILLE Primary Highway -,22 Secondary Highway Railways 752 Existing NGTLST System CAROLINE -,54 Licensed Pipeline (Foreign) RICINUS AIR CADET CAMP River /ST734 Creek CLEARWATER RIVER ST591 Lake / Waterbody City / Town CRAMMOND First Nations -,22 BURNSTICK Metis Reserve LAKE Military Reserve 0 2 4 8 12 16 ST734 Kilometers JAMES 1:175,000 RIVER BRIDGE Plans and Profiles of: EDSON MAINLINE EXPANSION PROJECT (Alford Creek Section) Canadian Energy Regulator Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity (GC-133) NOVA GAS TRANSMISSION LTD. Document No: 075621-MSI-G-MP-0269_01 The information contained herein is compiled from various government and industry sources, subject to copyright, and includes but is not limited to: © Government of Alberta 2009, © Department of Natural Resources Canada, All rights reserved. Midwest Surveys Inc. and its data suppliers provide no warranty regarding the accuracy or completeness of this information, and assume no liability for the interpretation or -

Annual Report 05/06

CONSERVATION THROUGH COLLABORATION wildlife fish habitat annual report 05/06 Our Vision We see an Alberta where there is good stewardship of our natural biological resources; where habitats are maintained and improved; and where people work together so future generations can value, enjoy and use these resources. Our Mission We work to conserve, protect and enhance our natural biological resources. 2 Annual Report 2005/2006 Annual Report 2005/2006 1 .02 Chairman’s Message .03 Managing Director’s Message .04 Financial Highlights .08 Our Story .10 Our Team .16 Our Strategy .32 Conservation Funding Partners in Conservation .37 Photography: The Alberta Conservation Association wishes to thank the following photographers who contributed to this publication: David Fairless, Kris Kendell, Robert Anderson and Gordon Court. 2 Annual Report 2005/2006 Annual Report 2005/2006 1 Chairman’s message It is no secret that Alberta is a prosperous, rapidly Approximately $7,000,000 in core funding from annual levies applied to growing province. Nor should it be a surprise angling and hunting licences along with key partnerships allow us to focus on to anyone that with this prosperity comes conserving and restoring our wild resources so that the hunting, angling and tremendous pressure and increased demands on recreational opportunities you appreciate today are available in the future. Alberta’s wildlife, fish, and habitat resources. This combination of rapid population and industrial growth means that As an organization we are constantly challenged to do more and, I can promise Alberta’s landscape is constantly evolving with land use priorities as diverse as you, we are doing the best we can with very limited resources. -

A Review of Information on Fish Stocks and Harvests in the South Slave Area, Northwest Territories

A Review of Information on Fish Stocks and Harvests in the South Slave Area, Northwest Territories DFO L b ary / MPO Bibliotheque 1 1 11 0801752111 1 1111 1 1 D.B. Stewart' Central and Arctic Region Department of Fisheries and Oceans Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N6 'Arctic Biological Consultants Box 68, St. Norbert Postal Station 95 Turnbull Drive Winnipeg, MB, R3V 1L5. 1999 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2493 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribution is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts and indexed in the Department's annual index to scientific and technical publications. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 901-1425 were issued as Manuscript Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 1426-1550 were issued as Department of Fisheries and the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Manuscript Reports. -

The Suncor - Winagami Lake Conservation Project, 2003-2004

The Suncor - Winagami Lake Conservation Project, 2003-2004 CCONSERVATIONONSERVATION RREPORTEPORT SSERIESERIES The Alberta Conservation Association is a Delegated Administrative Organization under Alberta’s Wildlife Act. CCONSERVATIONONSERVATION RREPORTEPORT SSERIESERIES 25% Post Consumer Fibre When separated, both the binding and paper in this document are recyclable The Suncor-Winagami Lake Conservation Project, 2003-2004 Cedar Chittenden Alberta Conservation Association Bag 900-26, 96th Avenue Peace River, Alberta T8S 1T4 Ed Kolodychuk Alberta Conservation Association Bag 900-26, 96th Avenue Peace River, Alberta T8S 1T4 Report Series Co-editors GARRY J. SCRIMGEOUR DAVID FAIRLESS Alberta Conservation Association Alberta Conservation Association Baker Centre Postal Outlet 7 th Floor O.S. Longman Building P.O. Box 40027 6909-116 Street Edmonton, AB, T5J 4M9 Edmonton, AB, T6H 4P2 Conservation Report Series Types: Data & Technical ISBN printed: 0-7785-4105-3 ISBN online: 0-7785-4106-1 ISSN printed: 1712-2821 ISSN online: 1712-283X Publication Number: T/085 Disclaimer: This document is an independent report prepared by the Alberta Conservation Association. The authors are solely responsible for the interpretations of data and statements made within this report. Reproduction and Availability: This report and its contents may be reproduced in whole, or in part, provided that this title page is included with such reproduction and/or appropriate acknowledgements are provided to the authors and sponsors of this project. Suggested citation: Chittenden, C., Kolodychuk, E. 2005. The Suncor-Winagami Lake Conservation Project, 2003-2004. Data report, D-2004-013, produced by Alberta Conservation Association, Peace River, Alberta, Canada. 14 pp. + Apps. Cover photo credit: David Fairless Content photo credit: C .Chittenden & E. -

Trip to Yukon and Alaska Summer 2011

Trip to Yukon and Alaska Summer 2011 by Sylvia R. Gallagher Photographs by Jim & Sylvia Gallagher Part V 4:45 pm, Sunday, August 21, 2011 Pine Lake Territorial Park, nr. Haines Junction, YK We've just finished two days of driving, about 150-170 miles each day. Yesterday, Sat., Aug. 20, we drove east on the Alaska Hwy. from Tok. The first part of it was along the border of Teslin National Wildlife Refuge. There the road went up and down on hills created by ice age glaciers and by wind-blown volcanic debris. Scenic roadside stops showed panoramic views of the bottomlands--bright green muskeg dotted with spindly dark green Black Spruce trees and interspersed with countless blue ponds of all sizes. Off in the distance were the mountains, which were somewhat veiled in clouds. The weather was mostly overcast, but the cloud formations themselves were endlessly variable. Just before we reached the Canadian border I saw the only Northern Shrike of the entire trip. I only got a glimpse of it on a utility wire beside the road. It was sort of dark, so I suspect it was a juvenile, but I never got my binoculars on it because we were moving along, albeit slowly. Crossing the border into Canada was easy this time, so we've had two unpleasant experiences followed by two easy ones on this trip. However, after we entered Yukon, the road became annoyingly slow with really deep frost heaves and lots of broken pavement. Much of this damage was difficult to see coming, so we finally settled on 40-45 mph and hoped for the best. -

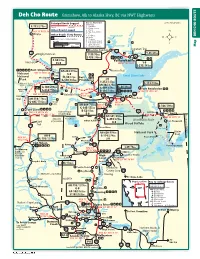

Deh Cho Route Grimshaw, AB, to Alaska Hwy, BC Via NWT Highways

Deh Cho Route Grimshaw, AB, to Alaska Hwy, BC via NWT Highways Key to Advertiser © The MILEPOST® Principal Route Logged Services -Camping C-173/278km Paved Unpaved C D -Dump Station Other Roads Logged d -Diesel N63˚16’ W123˚36’ G -Gas (reg., unld.) r -Ice e Wrigley I v Other Roads Ferry Routes i L -Lodging R Slemmon Lake M -Meals e f DEH CHO ROUTE Refer to Log for Visitor Facilities P -Propane i -Car Repair (major) n Scale R t k r -Car Repair (minor) w t o 0 20 Miles l S -Store (grocery) Marion l Map 0 20 Kilometres -Telephone (pay) Russell Lake e T Lake Y PRae-Edzo/Behchoko Ingraham Trail 3 Prosperous 1 w Lake Prelude L. Y-43/69km Wrigley Extension Y-59/95km 4 Tibbett L. M J-153/246km SbP Reid L. wt ac C-38/61km Yellowknife Free Ferry ke Y-0 nz FS-0 N62˚27’ W114˚21’ ie J-212/341km SwtbP Fort Simpson Frontier Trail AH-244/393km Mills 3 Nahanni N61˚51’ W121˚20’ w Free C-0 Lake Ferry wt Great Slave Lake National Checkpoint FS-38/61km Fort bP J-0 Park er G-550/885km Providence Riv 1 Y-212/341km Nahanni Butte R E-114/183km 4,579 ft./1,396m iver AH-385/620km Sw A-180/290km w G-409/659km E-24/38km Nahanni▲ Fort Resolution bP G-614/988km r Butte ive w B-116/186km wtbP N61˚10’ W113˚41’ R ut t N61˚04’ Kakisa N61˚05’ W122˚51’ Tro Waterfalls Route w Hay 6 W117˚30’ Lake S Liard t 1 River w l Trout w a sa Pine Point aki R v Trail AH-110/176km Lake t K iv 2 5 er e G-685/1102km Trout Tathina Lake Enterprise N60˚48’ Lake t AH-449/723km N60˚33’ P W115˚47’ w R E-186/300km Dogface W116˚08’ iv G-345/555km e wtbP Lake r d Fort Liard SwbP r NORTHWEST B-52/83km -

Reconstructing the Confluence Zone Between Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets Along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, Southwest Alberta

This is a repository copy of Reconstructing the confluence zone between Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, southwest Alberta. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/105138/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Utting, D., Atkinson, N., Pawley, S. et al. (1 more author) (2016) Reconstructing the confluence zone between Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, southwest Alberta. Journal of Quaternary Science, 31 (7). pp. 769-787. ISSN 0267-8179 https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.2903 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Reconstructing the confluence zone between Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets along the Rocky Mountain Foothills, south-west Alberta Daniel J. Utting1, Nigel Atkinson1, Steven Pawley1, Stephen J.