UNIVERSITY of the PHILIPPINES Bachelor of Arts in Broadcast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No

The Politics of Naming a Movement: Independent Cinema According to the Cinemalaya Congress (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Philippine Humanities Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, December 2011, pp. 76- 110 ISSN 0031-7802 © 2011 University of the Philippines 76 THE POLITICS OF NAMING A MOVEMENT: INDEPENDENT CINEMA ACCORDING TO THE CINEMALAYA CONGRESS (2005-2010) PATRICK F. CAMPOS Much has been said and written about contemporary “indie” cinema in the Philippines. But what/who is “indie”? The catchphrase has been so frequently used to mean many and sometimes disparate ideas that it has become a confusing and, arguably, useless term. The paper attempts to problematize how the term “indie” has been used and defined by critics and commentators in the context of the Cinemalaya Film Congress, which is one of the important venues for articulating and evaluating the notion of “independence” in Philippine cinema. The congress is one of the components of the Cinemalaya Independent Film Festival, whose founding coincides with and is partly responsible for the increase in production of full-length digital films since 2005. This paper examines the politics of naming the contemporary indie movement which I will discuss based on the transcripts of the congress proceedings and my firsthand experience as a rapporteur (2007- 2009) and panelist (2010) in the congress. Panel reports and final recommendations from 2005 to 2010 will be assessed vis-a-vis the indie films selected for the Cinemalaya competition and exhibition during the same period and the different critical frameworks which panelists have espoused and written about outside the congress proper. Ultimately, by following a number PHILIPPINE HUMANITIES REVIEW 77 of key and recurring ideas, the paper looks at the key conceptions of independent cinema proffered by panelists and participants. -

Si Judy Ann Santos at Ang Wika Ng Teleserye 344

Sanchez / Si Judy Ann Santos at ang Wika ng Teleserye 344 SI JUDY ANN SANTOS AT ANG WIKA NG TELESERYE Louie Jon A. Sánchez Ateneo de Manila University [email protected] Abstract The actress Judy Ann Santos boasts of an illustrious and sterling career in Philippine show business, and is widely considered the “queen” of the teleserye, the Filipino soap opera. In the manner of Barthes, this paper explores this queenship, so-called, by way of traversing through Santos’ acting history, which may be read as having founded the language, the grammar of the said televisual dramatic genre. The paper will focus, primarily, on her oeuvre of soap operas, and would consequently delve into her other interventions in film, illustrating not only how her career was shaped by the dramatic genre, pre- and post- EDSA Revolution, but also how she actually interrogated and negotiated with what may be deemed demarcations of her own formulation of the genre. In the end, the paper seeks to carry out the task of generically explicating the teleserye by way of Santos’s oeuvre, establishing a sort of authorship through intermedium perpetration, as well as responding on her own so-called “anxiety of influence” with the esteemed actress Nora Aunor. Keywords aura; iconology; ordinariness; rules of assemblage; teleseries About the Author Louie Jon A. Sánchez is the author of two poetry collections in Filipino, At Sa Tahanan ng Alabok (Manila: U of Santo Tomas Publishing House, 2010), a finalist in the Madrigal Gonzales Prize for Best First Book, and Kung Saan sa Katawan (Manila: U of Santo To- mas Publishing House, 2013), a finalist in the National Book Awards Best Poetry Book in Filipino category; and a book of creative nonfiction, Pagkahaba-haba Man ng Prusisyon: Mga Pagtatapat at Pahayag ng Pananampalataya (Quezon City: U of the Philippines P, forthcoming). -

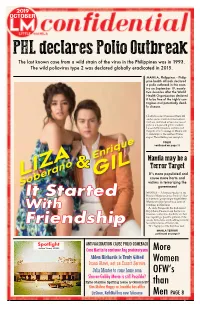

It Started Friendship

2019 OCTOBER PHL declares Polio Outbreak The last known case from a wild strain of the virus in the Philippines was in 1993. The wild poliovirus type 2 was declared globally eradicated in 2015. MANILA, Philippines -- Philip- pine health officials declared a polio outbreak in the coun- try on September 19, nearly two decades after the World Health Organization declared it to be free of the highly con- tagious and potentially dead- ly disease. Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said at a news conference that authori- ties have confirmed at least one case of polio in a 3-year-old girl in southern Lanao del Sur province and detected the polio virus in sewage in Manila and in waterways in the southern Davao region. Those findings are enough to POLIO continued on page 11 Enrique Manila may be a & Terror Target It’s more populated and LIZA GIL cause more harm and victims in terrorizing the Soberano government MANILA - A Deputy Speaker in the It Started House of Representatives thinks it’s like- ly that terror groups might target Metro Manila next after launching a series of bombings in Mindanao. With As such, Surigao del Sur 2nd district Rep. Johnny Pimentel said that law en- forcement authorities should be on their toes regarding a possible spillover of the attacks from down south, adding it would Friendship be costly in terms of human life. “It is highly possible that their next MANILA TERROR continued on page 9 Spotlight ANTI-VACCINATION CAUSE POLIO COMEBACK Au Bon Vivant, 1970’S Coco Martin to continue Ang probinsiyano More Alden Richards is Truly Gifted Ivana Alawi, not an Escort Service Women Julia Montes to come home soon OFW’s Sharon-Gabby Movie is still Possible? Kylie Maxine Spitting issue is Gimmick? than Kim Molina Happy sa Jowable box-office LizQuen, KathNiel has new Teleserye Men PAGE 8 1 1 2 2 2016. -

Dating the Gangster Brings Love to Life Restore Death Penalty

OCTOBER 2014 L.ittle M.anila Confidential Vote Manny Yanga Restore for Trustee Apple Death Boosts SEX Penalty DRIVE Heinous Crimes Prompt Call for Reimposition K ATHRYN MANILA - Senator Vicente Sotto III has reiterated the need to reimpose the death penalty amid a spate of heinous crimes – including child rape with murder. FREDDIE Bernardo “I stand once more advocating the return of Dating The the death penalty for certain heinous crimes like AGUILAR murder, rape and drug trafficking,” Sotto said in a privilege speech last September 24, the last Why He is Not session day of Congress as it went into a recess. “Let me ask my colleagues that we revisit A Fan Of the issue of the death penalty. There are now Singing Gangster Brings compelling reasons to do so. The next crime may be nearer to our homes, if not yet there. We must Contests act to a crime situation in the best way to protect society and the future generation,” he said. Love To Life Sotto cited several reported heinous crimes to prove his point such as the murder of movie actress Cherry Pie Picache’s 75-year-old mother; the murder of a seven-year-old girl in Pandacan; Remember...? Cordilleras Want the discovery under a jeepney of the body of a one-year-old girl, possibly raped; the arrest of six resort crashers for rape, robbery; the arrest of Moro Autonomy Law three suspects in the rape-slaying of a 26-year- old woman in Calumpit, Bulacan; the killing MANILA - As a Result of the peoples and indigenous cultural and rape of a 91-year-old woman among others. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Playing to Win at the Lopez Achievement Awards 2019 Story on Page 6

NOVEMBER 2019 www.lopezlink.ph Kapamilya gather anew for Palaro. Story on page 10. http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Playing to win at the Lopez Achievement Awards 2019 Story on page 6 Why ABS-CBN ‘Working Bally goes to is saving PH meaningfully’ Rockwell…page 12 films …page 3 at KCFI…page 9 Lopezlink November 2019 Biz News Lopezlink November 2019 Students get inspiration to SKY offers discount Viewers nationwide continue pursue dreams in PMC caravan to AAP members By Kane Choa By Kane Choa to tune in to ABS-CBN THE media industry is an ex- one is “too young to make an FILIPINOS across the coun- “FPJ’s Ang Probinsyano” “Starla” (28.1%). Completing morning block with 38% in citing yet challenging world. impact” in the entertainment try still tune in to ABS-CBN (35%) is still the top choice of the list are “Home Sweetie contrast to GMA’s 27%. But being part of it is worth industry. for their daily news and enter- viewers nationwide, while “The Home: Extra Sweet” (25.5%), The Kapamilya network it and meaningful, accord- ABS-CBN head of Creative tainment fare as the network General’s Daughter” (34.1%) “Maalaala Mo Kaya” (24.6%) emerged triumphant again in ing to media experts from Communications Management logged an average audience ended its run strongly. and “Rated K: Handa Na Ba Metro Manila as it registered a ABS-CBN who shared their Robert Labayen spoke about share of 44% in October versus “The Voice Kids” (30.2%) Kayo?” (23.2%). -

YIP SING INTERNATIONAL Please, No More Clothes For

The SUN October 2014 31 Pacquiao dinumog ng Please, no more clothes for relief: Dinky From Page 20 Also, DSWD now has a pre- thousands of rotting food soon replaced with new ones kababayan sa Central the past. arranged system in place to packs found in the DSWD being washed ashore. From Page 21 Amerikanong kickboxer na Another lesson she cited ensure faster delivery of relief warehouse, and of corpses Another reason was the “Masayang-masaya ako nakapgtala ng 20 panalo at was the need to have enough goods. “May kausap na being left unattended for days. difficulty of identifying the dahil marami akong walang talo. relief goods in storage to meet kaming trucking companies na On the spoiled food, she bodies, which prevented them nakilalang Pilipino rito sa “Hindi ko siya binabalewala demand. In the past, she said kikilos if they are needed,” said some of the donated items being taken away Hong Kong at nagulat ako sa sa labang ito dahil alam kong the DSWD had only 50,000 Soliman said. did not indicate their expiry immediately. This was dami ng mga tao sa kalye,” ani mas malakas siya at bata pa, at food packs ready to be given Despite admitting flaws in dates. especially true in Tacloban, Pacquiao, habang dinudumog desidido siyang manalo sa away; this will now be the system that prevented As for the corpses, she said where she said many of those ng mga Pilipina na noon ay labang ito, pero hindi doubled to 100,000 to ensure swift relief to those affected there had been so many of who died were migrants, and nagkataong nasa labas dahil mangyayari iyan,” ani supply. -

Filipino Centre Toronto's Sexin the PHL Embassies?

ittle anila LJUNE. - JULYM 2013.Confidential Why are there so many Filipino Centre Toronto’s Filipino Nurses in the US? by Rodel Rodis Pistahan Parada ng lechon, Singing Contests and Santacruzan This was the question posed to me by a are still Popular curious TV reporter on May 7, just three days after a stretch limousine traveling across the San Mateo Bridge carrying nine Filipino nurses to a bridal party suddenly burst into flames killing five of the occupants, including the bride. When she interviewed me in my law office in San Francisco, Ann Notarangelo, the reporter who is the weekend anchor of CBS 5’s Eyewitness News, explained that she was only asking the question because it was on the minds of her viewers. She thought I might know the answer as I taught Filipino American History at San Francisco State University and I am the legal counsel of the Philippine Nurses Association of Northern California. Plus, I Reina delas Flores Nica Victa is one of the reinas at the Santacruzan at FCT’s Pistahan. INSET FROM TOP, Newly-crowned PIDC Little Miss added, I am also married to a Filipino nurse. Philippines Britney Waito sings at the Pistahan; Michael Magali is the winner in the singing contest in the adult division; The Blessed Virgin Mary Ann said that she was frankly surprised to was escorted by the Hermanos and Hermanas; KC Partridge is one of the Ave Maria girls; Reina Banderada, who symbolizes the arrival of learn that 20% of all the registered nurses in Christianity was represented by the 2013 Miss Philippines of PIDC, Lauren Fernandez, is escorted by Philip Beloso. -

Filipino Star July 2012 Issue

Vol. XXX, No. 7 JULY 2012 http://www.filipinostar.org It's fiesta time for Filipinos in Montreal and suburbs. By W. G. Quiambao Mackenzie King park was chock-full of activities last July 15 during the FAMAS Pista sa Nayon, one of the much-anticipated events by many Filipinos in Montreal and suburbs. Friends seeing friends they haven’t seen for a while, music lovers listening to Filipino songs, women playing volleyball, kids enjoying pabitin (a rack of items is suspended over a crowd who attempt to grab at the stuff as the wooden rack is lowered and raised several times until everything is gone), revellers enjoying A few games of volleyball, arranged and managed by Mercy Sia Umipig and played by all-girl teams, was part of Pista sa Nayon (Photo: B. Sarmiento) a bounty of delicious foods - these are some of the activities during Pista sa Part of Ambassador Leslie B. bond of unity in a foreign setting." Nayon in the Philippines which are also Gatan's message read, "I wish to The tradition of the Pista sa practiced in Montreal every year. extend my heartfelt and warm Nayon dates back to centuries to the “Today, we celebrate the very congratulations to the Officers and rural areas and town in the Philippines. best of being Filipino," said Au Osdon, members of the Filipino Association of During Pista sa Nayon (called town FAMAS president. "The Bayanihan Montreal & Suburbs for their festival or fiesta), Filipinos would gather spirit is manifested by the support, sponsorship of the annual Pista sa for a fiesta in the middle of town to participation and involvement of so Nayon (town fiesta) with the main celebrate a good harvest. -

One-Of-A-Kind Finds at Power Plant Mall

OCTOBER 2011 www.lopezlink.ph Meet the Lopez Group’s ‘giving dozen’ Story on page 9 Gunning for Guinness 11.20.2011 Run for the Pasig River aims for two-peat! Story on page 8. http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph 1961 1989 2001 2007 2010 Braving new FIRST Philippine Holdings Corporation (FPH) turned a venerable 50 in June this year, and the celebration is far from over. horizons On September 21, 2011, chairman Federico R. Lopez (FRL) and chairman emeritus Oscar M. Lopez (OML) waxed nostalgic at the company’s appreciation cocktails held at the Makati Shangri-La. At the same time, the evening’s theme—“Braving New Horizons”—served notice that FPH was looking ahead to the next 50 years even as it reflected on the past 50. Turn to page 6 The ‘Biggest Loser’ One-of-a-kind finds finale this October! at Power Plant Mall 2010 Business Excellence …page 4 …page 12 Awards winners …page 2 Lopezlink October 2011 BIZ NEWS NEWS Lopezlink October 2011 BIZ EXCELLENCE EDC bags prestigious IFC Asian Eye is top Nine teams win LAAs Client Leadership Award PH eye center THE International Finance projects on health, education the Top Eye Center brand of Corporation (IFC) selected and livelihood. choice of consumers, besting Energy Development Corpo- “This is indeed a solid tes- 43 others. ration (EDC) as this year’s re- tament to our groundbreak- Asian Eye, which marked cipient of the prestigious Client ing and sustainable efforts to its 10th anniversary in Sep- Leadership Award, citing the achieve development in our tember, also received the high- geothermal leader’s exemplary host sites where we serve 43 est overall Trusted Brand rat- accomplishments in opera- villages and 18,000 house- ing, including values covering tional excellence, sustainability, holds,” EDC president and trustworthiness, credibility, environmental management, COO Richard Tantoco said. -

Pnoy M Y 2 K -V Le T E! Debut G

LOTTO RESULTS 4 dIgIT 6/55 gRand loTTo 27 28 25 16 05 09 5 3 3 3 Py urse bd 6/45 mEga loTTo EZ2 s SUa Obm 26 05 17 33 01 39 24 25 newsPahina 3 Pulitika • showbiz • sPorts • scandal • tsismis n opinion pag- Araw ng usapan Centro natin mga puso Vol. 1 no. 273 • HUWEBES • PEBRERo 14, 2013 • ISSn22440593 Pahina 4 vic somintac www.ssstcetr.cm Today’S WEaTHER P10 Ggm bwl s kmpy newsp ahina 3 Cludy 31°C newsPahina 2 TEAM PNOY Trillanes pasimuno AYAW MAG-DILAW! AAARANGKADA pa lamang ng kampanyahan paraK sa national post ValEnTInE’S day kaugnay ng nalalapit Excite tier it s p-s na May 13 elections, pi bukk hi p- pero tila pasaway pkw k pi arw agad ang ilang Pus. Itoh Son kandidato sa ilalim ng Team PNoy dahil sa pagpapatupad ng sariling polisiya. Isa rito si re-electionist Senator Antonio Trillanes na kandidato ng Nacionalista Party (NP) sa ilalim ng Team PNoy. newsPahina 2 Vlete news Pnoy my 2 Pahina 2 cocert tckets Ka-ValEnTInE! Jessc Hii is kui w k-Vlete! Debut gme i ‘K-Vetie’ i Pu t Colto, Bei aqui III wi pr L.a. Teoro los -curtes c khp,bispers blg Gebr Vetie’s d si ms. Turis Cesr, gp-lm ky ERaP bgo pmgy Iterti 2012 wier Rizzii aexis plyer, plpk? gez t ms. Uiverse 2012 1st Ruer- gw g bopc p Myor Lm ? Up Jie mri Tu. showbizPahina 7 sportszPahina 9 showbizPahina 6 Malacañang Photo Bureau Centro NEWS www.pssst.com.ph 2 HUWEBES • PEBRERO 14, 2013 Ecowaste Coalition, NBI tumanggi sa dismayado sa Team PNoy suicide ni Aranas “HINDI ako magkakalat ng basura sa lansangan.. -

The Eat Bulaga Star in Full Bloom

ittle anila L.M.Confidential APRIL 2014 Fil-Am Teen charged in Aid Food World Trade Thrown or Centre stunt Spoiled TACLOBAN CITY—Elation turned to Prostitution in horror for typhoon survivors in Barangay Gacao in Palo, Leyte, when maggots Singapore crawled out of the food packs that were distributed to them as relief. Reports of the distribution of rotten food followed two other incidents in the province in which food aid that had gone Cocaine bad was reported buried. Barangay Chairman Panchito Cortez confiscated said he saw residents converging on the barangay hall waiting for food packs delivered by the Municipal Social Welfare in Davao and Development Office of Palo. When they opened the boxes, however, worms as big as grains of rice crawled out of tetra packs and cup noodles. Biscuits were expired, and even the bottled mineral PAULEEN DND aks why water looked murky, Cortez said. Cortez said the goods were received by activists do Councilwoman Maria Anna Docena, and included 50 boxes of instant coffee, five not protest sacks of assorted biscuits, cup noodles, instant viand in tetra packs and five boxes of mineral water. against China Cortez said he immediately went to the Palo town hall and confronted MSWD LUNA officer Rosalina Balderas, who admitted that the goods came from their office. She said she didn’t know the food was Paris Hilton in already spoiled and infested with worms, Cortez added. The Eat Bulaga Pampanga Balderas admitted that truckloads of expired and spoiled food aid were dumped and buried in an open dumpsite in Barangay.