The Human Dimensions of ATV Use on the Island Portion of Newfoundland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book. -

Till Geochemical Surveys and Preliminary Quaternary Mapping of the Burin Peninsula and Adjacent Areas

Current Research (2007) Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources Geological Survey, Report 07-1, pages 197-214 TILL GEOCHEMICAL SURVEYS AND PRELIMINARY QUATERNARY MAPPING OF THE BURIN PENINSULA AND ADJACENT AREAS M.J. Batterson and D.M. Taylor Geochemistry, Geophysics and Terrain Sciences Section ABSTRACT A regional till geochemistry survey was completed on the Burin Peninsula. Till was sampled at a density ranging from 1 sample per 1 km2 in areas of good access, to 1 sample per 4 km2, where helicopter-support was required; 748 samples were collected during this survey to supplement 914 samples collected in adjacent areas in 2005. In addition, 135 newly recorded ice-flow indicators were recorded and mapped to reconstruct the palaeo ice-flow history of the survey area; the reconstruc- tion was supplemented by geomorphic data shown on the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) image for the area. Striation and landform evidence confirm that a regional southward (south to southeastward) ice-flow event, which cov- ered the entire study area, crossed the Burin Peninsula. The striations are generally fresh and unweathered, although some weathered facets were noted. The consistency of flow patterns across the area suggests that they are of the same age as those interpreted as late Wisconsinan in central and eastern Newfoundland; this ice flow produced most of the glacial streamlined landforms in the area. The southward ice flow was followed by a regionally extensive westward (southwest to northwest) ice flow that crossed the Burin Peninsula from Placentia Bay to Fortune Bay. The evidence for this event is crossing striations; however, the source of this ice flow remains uncertain. -

Labrador; These Will Be Done During the Summer

Fisheries Peches I and Oceans et Oceans 0 NEWFOUNDLAND REGION ((ANNUAL REPORT 1985-86 Canada ) ceare SMALL CRAFT HARBOURS BRANCH Y.'• ;'''' . ./ DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND OCEANS NEWFOUNDLAND REGION . 0 4.s.'73 ' ANNUAL REPORT - 1985/86 R edlioft TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Overview and Summary 1 2. Small Craft Harbours Branch National Planning Framework 3 3. Long Range Planning: Nfld. Region 8 4. Project Evaluation 10 5. Harbour Maintenance and Development Programs 11 6. Harbour Operations 16 7. Budget Utilization (Summary) 1985/86 17 APPENDICES 1. Photos 2. Harbour Classification 3. Minimum Services Offered 4. Condition Rating Scale 5. Examples of Project Type 6. Project Evaluation 7. Regular Program Projects 1985/86 8. Joint SCH-Job Creation Projects 1984/85/86 9. Joint SCH-Job Creation Projects 1985/86/87 10. Dredging Projects Utilizing DPW Plant 11. Advance Planning 12. Property Acquisition Underway 1 OVERVIEW AND SUMMARY Since the establishment of Small Craft Harbours Branch of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in 1973, the Branch has been providing facilities such as breakwaters, wharves, slipways, gear storage, shore protection, floats and the dredging of channels and basins, in fishing and recreational harbours within the Newfoundland Region. This third annual report produced by Small Craft Harbours Branch, Newfoundland Region, covers the major activities of the Branch for the fiscal year 1985/86. During the fiscal year continuing efforts were made towards planning of the Small Craft Harbours Program to better define and priorize projects, and to maximize the socio-economic benefits to the commercial fishing industry. This has been an on-going process and additional emphasis was placed on this activity over the past three years. -

Garnish Burin – Marystown

Burin Peninsula Voluntary Clusters Project Directory of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations Areas including: Placentia West Fortune Bay East Grand Bank - Fortune Frenchman’s Cove - Garnish Burin – Marystown Online Version Directory of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations on the Burin Peninsula Community Sector Council Newfoundland and Labrador The Community Sector Council Newfoundland and Labrador (CSC) is a leader in the voluntary community sector in Canada. Its mission is to promote the integration of social and economic development, encourage citizen engagement and provide leadership in shaping public policies. Our services include conducting research to help articulate the needs of the voluntary community sector and delivery of training to strengthen organizations and build the skills of staff and volunteers. Acknowledgements Prepared with the assistance of Trina Appleby, Emelia Bartellas, Fran Locke, Jodi McCormack, Amelia White, and Louise Woodfine. Many thanks to the members of the Burin Peninsula Clusters Pilot Advisory Committee for their support: Kimberley Armstrong, Gord Brockerville, Albert Dober, Everett Farwell, Con Fitzpatrick, Mike Graham, Elroy Grandy, Charles Hollett, Ruby Hoskins, Kevin Lundrigan, Joanne Mallay-Jones, Russ Murphy, and Sharon Snook. Disclaimer The listing of a particular service or organization should not be taken to mean an endorsement of that group or its programs. Similarly, omissions and inclusions do not necessarily reflect editorial policy. Also, while many groups indicated they have no problem being included in a version of the directory, some have requested to be omitted from an online version. Copyright © 2011 Community Sector Council Newfoundland and Labrador. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole, or in part, is forbidden without written permission. -

Municipal Fire Protection Services Report

A Report on the Operational Readiness of Municipal Fire Protection Services Throughout Newfoundland and Labrador 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................. 3 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................ 4 DESCRIPTION OF THE MUNICIPAL FIRE SERVICE ........................................ 6 MUNICIPAL FIRE PROTECTION ASSESSMENTS ......................................... 11 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................... 19 Appendix A - List of Newfoundland and Labrador Fire Departments ............. 20 Appendix B - Overview of Individual Municipal Fire Department Assessments by Fire Department ............................................................................... 25 Appendix C - FES-NL Municipal Fire Department Assessment Criteria ......... 40 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Report on the Operational Readiness of Municipal Fire Protection Services for Newfoundland and Labrador is based on data collected from the municipal fire protection services assessments which were completed over a period of 48 months, from September 2010 to August 31, 2014. The results of assessments performed for this report, and the analysis of the data, must be viewed in context with the current structure of the fire service throughout Newfoundland and Labrador and represents a snapshot in time. Some work has occurred since the initial assessments that may have contributed to certain -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

Anglican Church of Canada Tri-Diocesan Intercessions

ANGLICAN CHURCH OF CANADA TRI-DIOCESAN INTERCESSIONS 2015 DIOCESES OF EASTERN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR CENTRAL NEWFOUNDLAND WESTERN NEWFOUNDLAND Parish of Flower’s Cove…………………………………… 2 Anglican Life……………………………………………… 18 Parish of Fogo Island East…………………………………. 1 Canadian Forces Chaplaincies……………………………. 19 Parish of Fogo Island West………………………………… 1 Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, St. John’s……………… 12 Parish of Forteau…………………………………………… 3 Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist, Corner Brook……… 1 Parish of Fortune-Lamaline………………………………... 12 Diocese of Central Newfoundland………………………... 21 Parish of Gambo…………………………………………… 2 Diocese of Eastern Newfoundland and Labrador………… 20 Parish of Gander…………………………………………… 15 Diocese of Western Newfoundland………………………. 22 Parish of Gander Bay……………………………………… 1 Hospital Chaplains…..……………………………………. 19 Parish of Grand Bank……………………………………… 12 Parish of All Saints, Corner Brook……………………….. 9 Parish of Grand Bay……………………………………….. 4 Parish of All Saints, C. B. S………………………………. 5 Parish of Grand Falls………………………………………. 2 Parish of Badger’s Quay – Pool’s Island…………………. 10 Parish of Green Island……………………………………… 18 Parish of Bay de Verde…………………………………… 5 Parish of Greenspond/Newtown/Pound Cove……………… 15 Parish of Bay d’Espoir……………………………………. 6 Parish of Harbour Breton…………………………………… 11 Parish of Bay L’Argent…………………………………… 9 Parish of Harbour Grace……………………………………. 4 Parish of Bay of Islands…………………………………... 19 Parish of Heart’s Content…………………………………… 13 Parish of Bay Roberts /Coley’s Point…………………….. 4 Parish of Heart’s Delight…...………………………………. 4 Parish of Bay St. George/Parish of Stephenville Crossing Parish of Hermitage………………………………………… 17 (Cluster)…………………………………………………... 1 Parish of Holy Trinity………………………………………. 3 Parish of Bell Island……………………………………… 15 Parish of Indian Bay………………………………………… 9 Parish of Belleoram………………………………………. 7 Parish of Isle aux Morts/Foxroost/Margaree……………….. 11 Parish of Bonavista………………………………………. 11 Parish of King’s Cove………………………………………. -

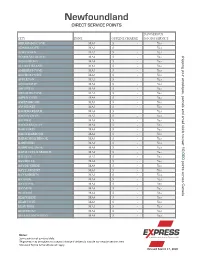

Newfoundland DIRECT SERVICE POINTS

Newfoundland DIRECT SERVICE POINTS DANGEROUS CITY ZONE OFFLINE CHARGE GOODS SERVICE ABRAHAMS COVE MA4 $ - Yes ADAMS COVE MA3 $ - Yes ADEYTOWN MA3 $ - Yes ADMIRALS BEACH MA4 $ - Yes shipping your envelopes, parcels and small skids to over AGUATHUNA MA4 $ - Yes ALLANS ISLAND MA3 $ - Yes AMHERST COVE MA3 $ - Yes ANCHOR POINT MA4 $ - Yes APPLETON MA3 $ - Yes AQUAFORTE MA4 $ - Yes ARGENTIA MA4 $ - Yes ARNOLDS COVE MA3 $ - Yes ASPEN COVE MA4 $ - Yes ASPEY BROOK MA3 $ - Yes AVONDALE MA3 $ - Yes BACK HARBOUR MA4 $ - Yes BACON COVE MA3 $ - Yes BADGER MA4 $ - Yes BADGERS QUAY MA4 $ - Yes BAIE VERTE MA4 $ - Yes BAINE HARBOUR MA4 $ - Yes BARACHOIS BROOK MA4 $ - Yes BARENEED MA3 $ - Yes BARRD ISLANDS MA4 $ - Yes 10,000 BARTLETTS HARBOUR MA4 $ - Yes BAULINE MA3 $ - Yes BAY BULLS MA4 $ - Yes points across Canada BAY DE VERDE MA4 $ - Yes BAY L'ARGENT MA4 $ - Yes BAY ROBERTS MA3 $ - Yes BAYSIDE MA4 $ - Yes BAYTONA MA4 $ - Yes BAYVIEW MA4 $ - Yes BEACHES MA4 $ - Yes BEACHSIDE MA4 $ - Yes BEAR COVE MA4 $ - Yes BEAU BOIS MA3 $ - Yes BEAUMONT MA4 $ - Yes BELL ISLAND FRONT MA4 $ - Yes Notes: Some points not serviced daily. Shipments may be subject to a beyond charge if delivery is outside our regular service area. Standard Terms & Conditions will apply. Revised March 17, 2020 Newfoundland DIRECT SERVICE POINTS DANGEROUS CITY ZONE OFFLINE CHARGE GOODS SERVICE BELL ISLAND MA4 $ - Yes BELLBURNS MA4 $ - Yes BELLEORAM MA4 $ - Yes BELLEVUE MA4 $ - Yes shipping your envelopes, parcels and small skids to over BELLMANS COVE MA4 $ - Yes BENOITS COVE MA4 $ - Yes BENTON -

Verbatim Report

/ PROVINCE OF NEWFOUNDLAND THIRTY-SIXTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NEWFOUNDLAND Volume 4 4th. Session Number 23 VERBATIM REPORT WEDNESDAY, APRIL 2, 1975 SPEAKER: THE HONOURABLE M. JAMES RUSSELL April 2, 1975 Tape 936 IB-l The House met at 3:00 P.M. Mr. Speaker in the Chair. MR. SPEAKER: Order, please! I understand we have in the galleries today eight Grade XI students from the Henry Gordon Academy at Cartwright, Labrador with their teacher, Mr. Pittman. On behalf of all the honourable members I welcome you to the galleries and trust that your visit here is most interesting. PRESENTING PETITIONS: HON. H.R.V. EARLE (MINISTER OF FINANCE): Mr. Speaker, I have a petition from the residents of St. Bernard's, Jacques Fontaine, Bay L'Argent, Little Bay East, Little Harbour East and Harbour Mille. This is all combined in one petition. The prayer of this petition is that the main road from these settlements to the Burin Highway be upgraded and paved. I, of course, support this petition, but in so doing I should like to say that particular stretch of road,which is approximately twenty miles in length1has had more• money spent on it in the past three years than in the past twenty years preceding that. There has been a tremendous amount spent on it. It is a very difficult road and very difficult road to build, a very expensive road. It is gradually being upgraded to full standard and hopefully when the Department of Transportation and Communications come through with their estimates we may get other work done this year which may go a long way towards completing the upgrading. -

Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries

Environment Canada Environnement Canada •• Fisheries Service des peches and Marine Service et des sciences de la mer 1 DFO ll ll i ~ ~~ll[lflll ~i~ 1 \11 1f1i! l1[1li eque 07003336 Codes Used in the Newfoundland Commercial and Recreational Fisheries by Don E. Waldron Data Record Series No. NEW/D-74-2 Resource Development Branch Newtoundland Region ) CODES USED IN THE NEWFOUNDLAND COMMERCIAL AND RECREATIONAL FISHERIES by D.E. Waldron Resource Development Branch Newfoundland Region Fisheries & Marine Service Department of the Environment St. John's, N'fld. February, 1974 GULF FlSHERIES LIBRARY FISHERIES & OCEANS gwt.IV HEOUE DES PECHES GOLFE' PECHES ET OCEANS ABSTRACT Data Processing is used by most agencies involved in monitoring the recreational and commercial fisheries of Newfoundland. There are three Branches of the Department of the Environment directly involved in Data Collection and Processing. The first two are the Inspection and the Conservation and Protection Branches (the collectors) and the Economics and Intelligence Branch (the processors)-is the third. To facilitate computer processing, an alpha-numeric coding system has been developed. There are many varieties of codes in use; however, only species, gear, ICNAF area codes, Economic and Intelligence Branch codes, and stream codes will be dealt with. Figures and Appendices are supplied to help describe these codes. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........... .. ... .... ... ........... ................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv LIST .or FIGURES ....... .................................... v LIST OF TABLES ............................................ vi INTRODUCTION l Description of Data Coding .............. ~ .. .... ... 3 {A) Coding Varieties ••••••••••••••• 3 (I) Species Codes 3 ( II ) Gear Codes 3 (III) Area Codes 3 (i) ICNKF 4 (ii) Statistical Codes 7 (a) Statistical Areas 7 (b) Statistical Sections 7 (c) Community (Settlement) Codes 17 (iii) Comparison of ICNAF AND D.O.E. -

Operational Area of Ambulance Services

GOVERNMENT OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND COMMUNITY SERVICES Board Services POLICY: Operational Area of POLICY NUMBER: EHS 2003-09-28 Ambulance Services ORIGINAL DATE: January 22, 1998 LAST REVISED DATE: November 1, 2005 I. PURPOSE: A. To define the primary operational/service area for ambulance services. B. To define the secondary operational/service area for ambulance services. II. POLICY: A. The area outlined in the Motor Carrier Certificate issued by the Board of Commissioners of Public Utilities shall be recognized by the Department as the primary operational territory of the service named on the license. This area shall be broken down into base service areas for services that are funded for more then one base. B. Services are required to respond to emergency calls within their primary service area. C. Calls originating outside an operator’s primary service area shall be deferred to the operator licensed for that area. If an operator cannot respond to a call within their service area then the next closest operator shall be contacted to perform the transport. D. As a secondary operational area operators have the right to respond to calls between any two points in the Province, upon the request of a medical doctor, registered nurse, or police officer and such calls shall only be honored for payment if transports are performed in accordance with all Departmental requirements including the policies applicable to outside service area authorizations. E. A call into the secondary operational area shall only be performed providing the primary operator for that service area cannot perform the transport and the secondary operator being requested is the next closest available operator to the incident who can perform the call in accordance with all Departmental requirements. -

Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Labrador and Environment Physical Parameters and Major Ions

Department of Municipal Affairs Tap Water Quality for Public Water Supplies in Newfoundland and Labrador and Environment Physical Parameters and Major Ions Serviced Area(s) Source Name Sample Date Alkalinity Colour Conductivity Hardness pH TDS TSS Turbidity Boron Bromide Calcium Chloride Fluoride Potassium Sodium Sulphate Units mg/L TCU µS/cm mg/L mg/L mg/L NTU mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L mg/L 15 6.5 - 8.5 500 1.0 5.0 250 1.5 200 500 Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality Aesthetic (A) or Contaminant (C) Parameter A A A C C A C A A Anchor Point Anchor Point Well Cove Brook Sep 17, 2019 106.00 10 243.0 120.00 8.28 158 0.60 LTD LTD 25.00 13 LTD LTD 7 1 Appleton Appleton (+Glenwood) Gander Lake (The Outflow) Aug 12, 2019 LTD 26 33.0 2.00 5.16 21 0.60 LTD LTD 1.00 7 LTD LTD LTD 1 Aquaforte Aquaforte Davies Pond Aug 21, 2019 12.00 14 107.0 LTD 7.79 70 0.40 LTD LTD LTD 24 LTD LTD 14 2 Arnold's Cove Arnold's Cove Steve's Pond (2 Intakes) Aug 21, 2019 12.00 10 61.0 5.00 7.21 40 0.60 LTD LTD 2.00 13 LTD LTD 9 1 Avondale Avondale Lee's Pond Sep 05, 2019 14.00 2 88.0 12.00 8.25 57 0.40 LTD LTD 5.00 15 LTD LTD 11 1 Baie Verte Baie Verte Southern Arm Pond Sep 26, 2019 LTD 19 34.0 5.00 5.05 22 0.20 LTD LTD 2.00 7 LTD LTD 2 1 Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Baine Harbour Pond Aug 29, 2019 8.00 83 38.0 5.00 7.33 25 0.40 LTD LTD 2.00 4 LTD LTD 4 2 Bartletts Harbour Bartletts Harbour Long Pond (same as Castors Sep 18, 2019 96.00 23 265.0 112.00 8.42 172 0.50 LTD LTD 25.00 22 LTD LTD 12 3 River North) Bauline Bauline #1 Brook Path Well Aug 15,