Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Diagnosis I and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency

biomedicines Review Premature Ovarian Insufficiency: Procreative Management and Preventive Strategies Jennifer J. Chae-Kim 1 and Larisa Gavrilova-Jordan 2,* 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-706-721-3832 Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 24 December 2018; Published: 28 December 2018 Abstract: Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is the loss of normal hormonal and reproductive function of ovaries in women before age 40 as the result of premature depletion of oocytes. The incidence of POI increases with age in reproductive-aged women, and it is highest in women by the age of 40 years. Reproductive function and the ability to have children is a defining factor in quality of life for many women. There are several methods of fertility preservation available to women with POI. Procreative management and preventive strategies for women with or at risk for POI are reviewed. Keywords: premature ovarian insufficiency; in vitro fertilization; donor oocyte; fertility preservation 1. Introduction Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is the loss of normal hormonal and reproductive function of ovaries in women before age 40 as the result of premature depletion of oocytes. POI is characterized by elevated gonadotrophin levels, hypoestrogenism, and amenorrhea, occurring years before the average age of menopause. Previously referred to as ovarian failure or early menopause, POI is now understood to be a condition that encompasses a range of impaired ovarian function, with clinical implications overlapping but not synonymous to that of physiologic menopause. -

The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio In

microorganisms Review The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease Spase Stojanov 1,2, Aleš Berlec 1,2 and Borut Štrukelj 1,2,* 1 Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Ljubljana, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (A.B.) 2 Department of Biotechnology, Jožef Stefan Institute, SI-1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia * Correspondence: borut.strukelj@ffa.uni-lj.si Received: 16 September 2020; Accepted: 31 October 2020; Published: 1 November 2020 Abstract: The two most important bacterial phyla in the gastrointestinal tract, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, have gained much attention in recent years. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio is widely accepted to have an important influence in maintaining normal intestinal homeostasis. Increased or decreased F/B ratio is regarded as dysbiosis, whereby the former is usually observed with obesity, and the latter with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Probiotics as live microorganisms can confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. There is considerable evidence of their nutritional and immunosuppressive properties including reports that elucidate the association of probiotics with the F/B ratio, obesity, and IBD. Orally administered probiotics can contribute to the restoration of dysbiotic microbiota and to the prevention of obesity or IBD. However, as the effects of different probiotics on the F/B ratio differ, selecting the appropriate species or mixture is crucial. The most commonly tested probiotics for modifying the F/B ratio and treating obesity and IBD are from the genus Lactobacillus. In this paper, we review the effects of probiotics on the F/B ratio that lead to weight loss or immunosuppression. -

The Relations Between Anemia and Female Adolescent's Dysmenorrhea

Universitas Ahmad Dahlan International Conference on Public Health The Relations Between Anemia and Female Adolescent’s Dysmenorrhea Paramitha Amelia Kusumawardani, Cholifah Diploma Program of Midwifery, Health Science Faculty , University of Muhammadiyah Sidoarjo Article Info ABSTRACT Keyword: Dysmenorrhea described as painful cramps in the lower abdomen that Anemia, occur during menstruation and the infection indications, pelvic disease Dysmenorrhea, moreover in the severe cases it caused fainted. The women who Female adolescents. complained dysmenorrhea problems mostly are who experience menstruation at any age. That means there is no limits age and usually dysmenorrhea often occur with dizziness, cold sweating, even fainted. In some countries the dysmenorrhea problem happens quite high as happened in the United States found 60-91% while in Indonesia amounted to 64.25%. as many as 45-75% of female adolescent experienced dysmenorrhea with the chronic or severe pain that effected to their everyday activities The number of teenagers who experience dysmenorrhea is due to high cases of anemia, irregular exercise, and lack of knowledge of nutritional status. In the previous study there are 85% of female adolescent experience dysmenorrhea. The method of this study is a correlational method with cross sectional approach. The data collecting method examining Hb levels. The population and sample of this study was 40 female adolescent The result showed that the female adolescent who had dysmenorrhea with anemia was 26 (92.4%). From the calculation by Exact Fisher the correlation between anemia and dysmenorrhea cases among female adolescent P <0.05 and p = 0.003, there was significant correlation between adolescent’s dysmenorrhea. Based on the result of statistic analysis, it can be concluded that the anemia can be categorized as one of dysmenorrhea causes. -

ICD10 Diagnoses FY2018 AHD.Com

ICD10 Diagnoses FY2018 AHD.com A020 Salmonella enteritis A5217 General paresis B372 Candidiasis of skin and nail A040 Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli A523 Neurosyphilis, unspecified B373 Candidiasis of vulva and vagina infection A528 Late syphilis, latent B3741 Candidal cystitis and urethritis A044 Other intestinal Escherichia coli A530 Latent syphilis, unspecified as early or B3749 Other urogenital candidiasis infections late B376 Candidal endocarditis A045 Campylobacter enteritis A539 Syphilis, unspecified B377 Candidal sepsis A046 Enteritis due to Yersinia enterocolitica A599 Trichomoniasis, unspecified B3781 Candidal esophagitis A047 Enterocolitis due to Clostridium difficile A6000 Herpesviral infection of urogenital B3789 Other sites of candidiasis A048 Other specified bacterial intestinal system, unspecified B379 Candidiasis, unspecified infections A6002 Herpesviral infection of other male B380 Acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis A049 Bacterial intestinal infection, genital organs B381 Chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis unspecified A630 Anogenital (venereal) warts B382 Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, A059 Bacterial foodborne intoxication, A6920 Lyme disease, unspecified unspecified unspecified A7740 Ehrlichiosis, unspecified B387 Disseminated coccidioidomycosis A080 Rotaviral enteritis A7749 Other ehrlichiosis B389 Coccidioidomycosis, unspecified A0811 Acute gastroenteropathy due to A879 Viral meningitis, unspecified B399 Histoplasmosis, unspecified Norwalk agent A938 Other specified arthropod-borne viral B440 Invasive pulmonary -

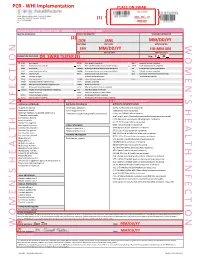

Womens Health Requisition Forms

PCR - WHI Implementation PLACE ON SWAB 10854 Midwest Industrial Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63132 MM DD YY Phone: (314) 200-3040 | Fax (314) 200-3042 (1) CLIA ID #26D0953866 JANE DOE v3 PCR MOLECULAR REQUISITION - WOMEN'S HEALTH INFECTION PRACTICE INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION *SPECIMEN INFORMATION (2) DOE JANE MM/DD/YY LAST NAME FIRST NAME DATE COLLECTED W O M E ' N S H E A L T H I F N E C T I O N SSN MM/DD/YY HH:MM AM SSN DATE OF BIRTH TIME COLLECTED REQUESTING PHYSICIAN: DR. SWAB TESTER (3) Sex: F X M (4) Diagnosis Codes X N76.0 Acute vaginitis B37.49 Other urogenital candidiasis A54.9 Gonococcal infection, unspecified N76.1 Subacute and chronic vaginitis N89.8 Other specified noninflammatory disorders of vagina A59.00 Urogenital trichomoniasis, unspecified N76.2 Acute vulvitis O99.820 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating pregnancy A64 Unspecified sexually transmitted disease N76.3 Subacute and chronic vulvitis O99.824 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating childbirth A74.9 Chlamydial infection, unspecified N76.4 Abscess of vulva B95.1 Streptococcus, group B, as the cause Z11.3 Screening for infections with a predmoninantly N76.5 Ulceration of vagina of diseases classified elsewhere sexual mode of trasmission N76.6 Ulceration of vulva Z22.330 Carrier of group B streptococcus Other: N76.81 Mucositis(ulcerative) of vagina and vulva N70.91 Salpingitis, unspecified N76.89 Other specified inflammation of vagina and vulva N70.92 Oophoritis, unspecified N95.2 Post menopausal atrophic vaginitis N71.9 Inflammatory disease of uterus, unspecified -

Menstrual Disorders Susan Hayden Gray, MD* Practice Gap 1

Article genital system disorders Menstrual Disorders Susan Hayden Gray, MD* Practice Gap 1. Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, and abnormal vaginal bleeding affect the majority of Author Disclosure adolescent females, impacting quality of life and school attendance. Patient-centered Dr Gray has disclosed adolescent care should include searching for, assessing, and managing menstrual concerns. no financial 2. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy in young relationships relevant adult women, and pediatricians should recognize, monitor, educate, and manage their to this article. This patients who fit the medical profile for PCOS based on any/all of the three sets of commentary does diagnostic criteria. contain a discussion of an unapproved/ Objectives After reading this article, readers should be able to: investigative use of a commercial product/ 1. Define primary and secondary amenorrhea and list the differential diagnosis for each. device. 2. Recognize the importance of a sensitive urine pregnancy test early in the evaluation of menstrual disorders, regardless of stated sexual history. 3. Know that polycystic ovary syndrome is a common cause of secondary amenorrhea in adolescents and may present with oligomenorrhea or abnormal uterine bleeding. 4. Recognize that eating disordered behaviors are a common cause of secondary amenorrhea and irregular bleeding, and treatment of the eating disordered behavior is the best recommendation to ensure resumption of regular menses and long-term bone health. 5. Know the differential diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding and describe the preferred treatment, recognizing the central importance of iron replacement. 6. Understand the prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and its role in causing recurrent school absence in young women, and describe its evaluation and management. -

Endometritis Caused by Chlamydia Trachomatis

Br J Vener Dis 1981; 57:191-5 Endometritis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis P-A MARDH,* B R M0LLER,t H J INGERSELV,* E NUSSLER,* L WESTROM,§ AND P W0LNER-HANSSEN§ From the *Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Lund, Sweden; the tlnstitute of Medical Microbiology, University of Aarhus, Denmark; the *Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Municipal Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; and the §Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital, Lund, Sweden SUMMARY Chlamydia trachomatis was found to be the aetiological agent of endometritis in three women with concomitant signs of salpingitis. All patients developed a significant antibody response to the organism. Chlamydia were recovered from aspirated uterine contents of two patients and darkfield examination of histological sections showed chlamydial inclusions in endometrial cells in one patient. Thus, C trachomatis can be recovered from the endometrium of patients in whom the cervical culture result is negative. In one patient curettage showed endometritis with a characteristic plasma-cell infiltration. The occurrence of chlamydial endometritis may explain why irregular bleeding is a common finding in patients with salpingitis. It also suggests a canalicular spread of chlamydia from the cervix to the Fallopian tubes. Introduction hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum by cotton- tipped wooden sticks. Specimens for the isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis has been associated with N gonorrhoeae from the cervix and rectum were cervicitis' and salpingitis,2 and perihepatitis may collected with cotton-tipped wooden swabs treated occur in women with chlamydial genital infection.3 with charcoal. Salpingitis caused by chlamydia4 and gonococci5 are histologically similar. Gonococcal salpingitis is an Endometrial contents endosalpingitis and the infection spreads to the For the collection of end6metrial contents, a plastic Fallopian tubes from the cervix via the tube (armoured with a mandrin) was introduced endometrium.5 Experimental salpingitis in monkeys through the cervical canal. -

Culdocentesis in Diagnosis of Disturbed Ectopic Pregnancy Still a Useful Procedure in Developing Countries

CULDOCENTESIS IN DIAGNOSIS OF DISTURBED ECTOPIC PREGNANCY STILL A USEFUL PROCEDURE IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Pages with reference to book, From 5 To 6 Tasneem Aslam Tariq ( Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi. ) Razia Korejo ( Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Jinnah Postgraduate Medical Centre, Karachi. ) ABSTRACT Over a period of 5 years culdocentesis was carried out in 156 cases of suspected ectopic pregnancy using needle aspiration through the pouch of Douglas. The result was positive in 134 cases, with 131 being true positive and 3 false positive. In 22 cases the result was negative, 6 of which were false negative. It is concluded that culdocentesis is an effective method of diagnosing disturbed ectopic pregnancy (JPMA 42: 5, 1992). INTRODUCTION Ectopic pregnancy, a clinical diagnosis in majority of cases is infrequently seen in our hospital. Since it can present with varied symptoms, diagnosis can be difficult in some cases. To increase the accuracy rate of preoperative diagnosis in suspected cases of ectopic pregnancy, various diagnostic procedures have been employed over the years. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of culdocentesis for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. PATIENTS AND METHOD The present study included 156 suspected cases of ectopic pregnancy admitted to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology between January, 1985 to December 1989. Culdocentesis was done in the operating theatre under aseptic precautions with or without general anaesthesia depending on the certainty of the diagnosis. Urinary bladder was catheterized and gentle bimanual vaginal examination was done to confirm the previous vaginal findings. Sims speculum was introduced in the vagina and posterior lip of cervix was held gently with a Vulsellum forceps, pulled upwards and forwards exposing the posterior fornix. -

Women's Health Course Guide

Course Guide for Women’s Health 1 Approach to the Patient The OB/GYN History Rationale: A gynecological evaluation is an important part of primary health care and preventive medicine for women. A gynecological assessment should be a part of every woman’s general medical history and physical examination. Certain questions must be asked of every woman, whereas other questions are specific to particular problems. To accomplish these objectives, optimal communication must be achieved between patient and physician. The student will demonstrate the ability to: A. Perform a thorough obstetric-gynecologic history as a portion of a general medical history, including: 1. Chief complaint 2. Present illness 3. Menstrual history 4. Obstetric history 5. Gynecologic history 6. Contraceptive history 7. Sexual history 8. Family history 9. Social history B. Interact with the patient to gain her confidence and to develop an appreciation of the effect of her age, racial and cultural background, and economic status on her health; C. Communicate the results of the obstetric-gynecologic and general medical history by well-organized written and oral reports. The OB/GYN Examination Rationale: An accurate examination complements the history, provides additional information and helps determine diagnosis and guide management. It also provides an opportunity to educate and reassure the patient. The student will demonstrate the ability to: A. Interact with the patient to gain her confidence and cooperation, and assure her comfort and modesty B. Perform a painless obstetric-gynecologic examination as part of a woman’s general medical examination, including: 1. Breast examination 2. Abdominal examination 3. Complete pelvic examination 4. -

AMENORRHOEA Amenorrhoea Is the Absence of Menses in a Woman of Reproductive Age

AMENORRHOEA Amenorrhoea is the absence of menses in a woman of reproductive age. It can be primary or secondary. Secondary amenorrhoea is absence of periods for at least 3 months if the patient has previously had regular periods, and 6 months if she has previously had oligomenorrhoea. In contrast, oligomenorrhoea describes infrequent periods, with bleeds less than every 6 weeks but at least one bleed in 6 months. Aetiology of amenorrhea in adolescents (from Golden and Carlson) Oestrogen- Oestrogen- Type deficient replete Hypothalamic Eating disorders Immaturity of the HPO axis Exercise-induced amenorrhea Medication-induced amenorrhea Chronic illness Stress-induced amenorrhea Kallmann syndrome Pituitary Hyperprolactinemia Prolactinoma Craniopharyngioma Isolated gonadotropin deficiency Thyroid Hypothyroidism Hyperthyroidism Adrenal Congenital adrenal hyperplasia Cushing syndrome Ovarian Polycystic ovary syndrome Gonadal dysgenesis (Turner syndrome) Premature ovarian failure Ovarian tumour Chemotherapy, irradiation Uterine Pregnancy Androgen insensitivity Uterine adhesions (Asherman syndrome) Mullerian agenesis Cervical agenesis Vaginal Imperforate hymen Transverse vaginal septum Vaginal agenesis The recommendations for those who should be evaluated have recently been changed to those shown below. (adapted from Diaz et al) Indications for evaluation of an adolescent with primary amenorrhea 1. An adolescent who has not had menarche by age 15-16 years 2. An adolescent who has not had menarche and more than three years have elapsed since thelarche 3. An adolescent who has not had a menarche by age 13-14 years and no secondary sexual development 4. An adolescent who has not had menarche by age 14 years and: (i) there is a suspicion of an eating disorder or excessive exercise, or (ii) there are signs of hirsutism, or (iii) there is suspicion of genital outflow obstruction Pregnancy must always be excluded. -

Bacteroides Fragilis Group Is on the Fast Track to Resistance

antibiotics Article Surveillance of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Anaerobe Clinical Isolates in Southeast Austria: Bacteroides fragilis Group Is on the Fast Track to Resistance Elisabeth König 1,2, Hans P. Ziegler 1, Julia Tribus 1, Andrea J. Grisold 1 , Gebhard Feierl 1 and Eva Leitner 1,* 1 Diagnostic & Research Institute of Hygiene, Microbiology and Environmental Medicine, Medical University of Graz, A 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] (E.K.); [email protected] (H.P.Z.); [email protected] (J.T.); [email protected] (A.J.G.); [email protected] (G.F.) 2 Section of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical University of Graz, A 8010 Graz, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Anaerobic bacteria play an important role in human infections. Bacteroides spp. are some of the 15 most common pathogens causing nosocomial infections. We present antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) results of 114 Gram-positive anaerobic isolates and 110 Bacteroides-fragilis- group-isolates (BFGI). Resistance profiles were determined by MIC gradient testing. Furthermore, we performed disk diffusion testing of BFGI and compared the results of the two methods. Within Gram-positive anaerobes, the highest resistance rates were found for clindamycin and moxifloxacin Citation: König, E.; Ziegler, H.P.; (21.9% and 16.7%, respectively), and resistance for beta-lactams and metronidazole was low (<1%). Tribus, J.; Grisold, A.J.; Feierl, G.; For BFGI, the highest resistance rates were also detected for clindamycin and moxifloxacin (50.9% and Leitner, E. Surveillance of 36.4%, respectively). Resistance rates for piperacillin/tazobactam and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid Antimicrobial Susceptibility of were 10% and 7.3%, respectively. -

Sexually Transmitted Infections DST-1007 Mucopurulent Cervicitis (MPC)

Certified Practice Area: Reproductive Health: Sexually Transmitted Infections DST-1007 Mucopurulent Cervicitis (MPC) DST-1007 Mucopurulent Cervicitis (MPC) DEFINITION Inflammation of the cervix with mucopurulent or purulent discharge from the cervical os. POTENTIAL CAUSES Bacterial: • Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) • Neisserria gonorrhoeae (GC) Viral: • herpes simplex virus (HSV) Protozoan: • Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) Non-STI: • chemical irritants • vaginal douching • persistent disruption of vaginal flora PREDISPOSING RISK FACTORS • sexual contact where there is transmission through the exchange of body fluids • sexual contact with at least one partner • sexual contact with someone with confirmed positive laboratory test for STI • incomplete STI medication treatment • previous STI TYPICAL FINDINGS Sexual Health History • may be asymptomatic • sexual contact with at least one partner • increased abnormal vaginal discharge • dyspareunia • bleeding after sex or between menstrual cycles • external or internal genital lesions may be present with HSV infection • sexual contact with someone with confirmed positive laboratory test for STI Physical Assessment Cardinal Signs • mucopurulent discharge from the cervical os (thick yellow or green pus) and /or friability of the cervix (sustained bleeding after swabbing gently) BCCNM-certified nurses (RN(C)s) are responsible for ensuring they reference the most current DSTs, exercise independent clinical judgment and use evidence to support competent, ethical care. NNPBC January 2021. For more information or to provide feedback on this or any other decision support tool, email mailto:[email protected] Certified Practice Area: Reproductive Health: Sexually Transmitted Infections DST-1007 Mucopurulent Cervicitis (MPC) The following may also be present: • abnormal change in vaginal discharge • cervical erythema/edema Other Signs • cervicitis associated with HSV infection: o cervical lesions usually present o may have external genital lesions with swollen inguinal nodes Notes: 1.