CAS 2016/A/4874 Club Africain V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 the KA the Kick Algorithms ™

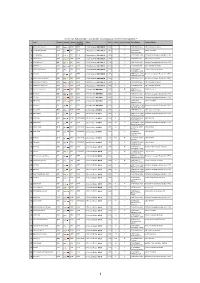

the-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 www.kickalgor.com the KA the Kick Algorithms ™ Club Country Country League Conf/Fed Class Coef +/- Place up/down Class Zone/Region Country Cluster Continent ⦿ 1 Manchester City FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,928 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 2 FC Bayern München GER GER � GER UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,907 -1 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 3 FC Barcelona ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,854 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 4 Liverpool FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,845 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 5 Real Madrid CF ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,786 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 6 Chelsea FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,752 +4 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⦿ 7 Paris Saint-Germain FRA FRA � FRA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,750 UEFA Western France / overseas territories Continental Europe ⦿ 8 Juventus ITA ITA � ITA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,749 -2 UEFA Central / East Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) Mediterranean Zone ⦿ 9 Club Atlético de Madrid ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,676 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 10 Manchester United FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,643 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 11 Tottenham Hotspur FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,628 -2 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⬇ 12 Borussia Dortmund GER GER � GER UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,541 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 13 Sevilla FC ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,531 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. -

Das Grosse Vereinslexikon Des Weltfussballs

1 RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS ALLE ERSTLIGISTEN WELTWEIT VON 1885 BIS HEUTE AFRIKA & ASIEN BAND 1 DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS DES VEREINSLEXIKON GROSSE DAS BAND 1 AFRIKA & ASIEN RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS BAND 1 AFRIKA UND ASIEN Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National- bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Copyright © 2019 Verlag Die Werkstatt GmbH Lotzestraße 22a, D-37083 Göttingen, www.werkstatt-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Gestaltung: René Köber Satz: Die Werkstatt Medien-Produktion GmbH, Göttingen ISBN 978-3-7307-0459-2 René Köber RENÉRené KÖBERKöber Das große Vereins- DasDAS große GROSSE Vereins- LEXIKON VEREINSLEXIKONdesL WEeXlt-IFKuOßbNal lS des Welt-F ußballS DES WELTFUSSBALLSBAND 1 BAND 1 BAND 1 AFRIKAAFRIKA UND und ASIEN ASIEN AFRIKA und ASIEN Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute 15 00015 000 Vereine Vereine aus aus 6 6 000 000 Städten/Ortschaften und und 228 228 Ländern Ländern 15 000 Vereine aus 6 000 Städten/Ortschaften und 228 Ländern 1919 000 000 farbige Vereinslogos Vereinslogos 19 000 farbige Vereinslogos Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Stadien, Erfolge, Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Spielerauswahl Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, -

1677 Alexis Enam V

Tribunal Arbitral du Sport Court of Arbitration for Sport Arbitration CAS 2008/A/1677 Alexis Enam v. Club Al Ittihad Tripoli, award of 20 May 2009 Panel: Mr Jean-Paul Burnier (France), President; Mr Rafik Dey Daly (Tunisia); Mr Guido Valori (Italy) Football Breach of the employment contract without just cause within the Protected Period Res judicata Nature of the damage suffered by the club Joint and several liability of the new club Standing to be sued of the club with respect to the sporting sanctions 1. The principle of res judicata ensures that whenever a dispute has been defined and decided upon, it becomes irrevocable, confirmed and deemed to be just (res judicata pro veritate habetur). The three elements of a res judicata are the same persons, the same object and the same cause. The exceptio res judicata is only admissible if all three elements are concurrently present. 2. The damage that a club may suffer when the player breaches his contract is of a triple nature. The “material damage” (damnum emergens) represents the actual reduction in the economic situation of the party who has suffered the damage. The “loss of profits” (lucrum cessans) represents the profit which could reasonably have been expected but that was not earned because of the breach. Finally, “non-pecuniary loss” refers to those losses which cannot immediately be calculated, as they do not amount to a tangible or material economic loss. 3. According to article 17 para. 2 of the FIFA Regulations, the player’s new club is jointly and severally liable with the player for the payment of the applicable compensation. -

8 Hassan Mostafa Zamalek SC, Egyptian Premier

8 Hassan Mostafa Zamalek SC, Egyptian Premier League (Egypt) not currently plaing for national team The profile for Hassan Mostafa Date of birth: 20.11.1979 Place of birth: Giza Age: 31 Height: 1,75 Nationality: Egypt Position: Midfield - Defensive Midfield Foot: right 352.000 £ Market value: 400.000 € Market value Details of market value National team career SN National team Matches Goals 21 Egypt 29 2 More info about Hassan Mostafa Contract until: 30.06.2011 Debut (Club): 07.08.2009* "Performance data of current season Competition Matches Goals Assists Minutes CAF-Champions League 2 - - - 1 161 Egyptian Premier League 16 2 1 - 5 1367 Total: 18 2 1 - 6 1528 Performance data for season 10/11 Competition Matches CAF-Champions League 2 - - - - - - - 1 - 161 Egyptian Premier League 16 2 - 1 7 - - - 5 684 1367 Total: 18 2 - 1 7 - - - 6 764 1528 CAF-Champions League - 10/11 pl. Match Result 1 Club Africain Tunis - Zamalek SC 4 : 2 90 2 Zamalek SC - Club Africain Tunis 2 : 1 71 70 Egyptian Premier League - 10/11 pl. Match Result 4 Zamalek SC - Ismaily SC 3 : 2 38 90 5 Zamalek SC - El Gouna FC 1 : 1 72 90 6 Smouha SC - Zamalek SC 1 : 3 x 89 88 7 Zamalek SC - Arab Contractors SC 1 : 0 90 8 Masr El Makasa - Zamalek SC 3 : 4 90 11 Zamalek SC - Masry Port Said 1 : 0 90 12 El Ahly Cairo - Zamalek SC 0 : 0 51 65 64 13 Zamalek SC - Ittehad Alexandria 4 : 3 90 14 Wadi Degla FC - Zamalek SC 0 : 2 1 90 15 Zamalek SC - Entag El Harby 0 : 0 90 16 Zamalek SC - Harras El Hodoud 2 : 1 1 90 17 Petrojet - Zamalek SC 1 : 2 1 52 90 18 Zamalek SC - Enppi Club 0 : 0 90 19 Ismaily SC - Zamalek SC 0 : 0 81 80 20 El Gouna FC - Zamalek SC 2 : 1 28 56 55 22 Arab Contractors SC - Zamalek SC 2 : 3 19 86 85 Performance data for season 08/09 Competition Matches Egyptian Premier League 14 - - - 1 - - 3 7 - 981 WM-Qualifikation Afrika 2 - - - 1 - - 2 - - 55 Total: 16 - - - 2 - - 5 7 - 1036 Egyptian Premier League - 08/09 pl. -

Les Lionnes Sauvent L'essentiel

SAMEDI 07 MARS 2020 www.lionindomptable.com (LION INDOMPTABLE VERSION NUMÉRIQUE) 90 Samedi 07 Mars 2020 CAF CHAMPIONS LEAGUE Le Cameroun souhaite accueillir CAMEROUN VS ZAMBIE 3-2 la finale de l’édition 2019-2020 = ELITE ONE Comment l’équipe de Dragon a été attaquée mercredi à Bamenda LES LIONNES SAUVENT SANCTION La FECAFOOT sans pitié pour L’ESSENTIEL Roger noah CONFIDENCES D’ANCIENS PAUL BAHOKEN « JE ME CONSIDÈRE COMME QUELQU’UN QUI A ÉTÉ CHAMPION D’AFRIQUE EN 1984 » C’est sans doute l’événement de sa carrière qui le marquera à jamais. Après avoir contribué à la qualification du Cameroun pour la Coupe d’Afrique des Nations 1984 en Côte d’Ivoire, Paul Bahoken avait été écarté de la tanière à quelques semaines du coup d’envoi de la compétition alors qu’on l’accusait injustement d’indiscipline après qu’il ait fait une suggestion sur le travail du médecin de l’équipe. CAMEROUN VS ZAMBIE 3-2 EL JO Samedi 07 Mars 2020 Les Lionnes assurent l’essentiel face à la Zambie A un pas d’une qualification directe pour (56e). Ngo Batoum quant à elle trouvait le poteau les Jeux Olympiques Tokyo 2020, les en voulant surprendre la portière zambienne sortie Lionnes Indomptables avaient intérêt à défendre hors de sa surface (69e). La pression bien négocier la manche aller du dernier camerounaise finissait par payer à la 73ème minute, tour des éliminatoires face à la Zambie, à lorsqu’oubliée dans la défense, AboudiOnguene domicile. Alain Djeumfa n’a pas souhaité reprenait victorieusement un centre venu de prendre de risque en faisant confiance aux NchoutNjoyaAjara sur le côté gauche. -

Football Football

4 7 0 0 - I I LES ESPAGNOLS VEULENT VENDRE I I N S S I - LEURS PARTS DANS MEDGAZ r e g l A ’ d n o i t i d E LE BONJOUR DU «SOIR» SONATRACH Comme il a dit lui, Mister Raffarin M. Raffarin a salué le travail à l'anglaise de M. Chérif Rahmani. C'est quoi travailler à l'anglaise ? Bosser avec le flegme britannique ? Si c'est EN POSITION ça, alors il faudra attendre le premier Algérien sur la Lune pour voir enfin un accord sur l'usine Renault. Si c'est travailler avec sérieux et efficacité, ce n'est pas très gentil pour l'ancien ministre de l'Industrie. Et comme M. PAGE 3 Raffarin a dit qu'il travaillait lui aussi comme un Anglais, ne faut-il pas DE FORCE ? comprendre que les deux méthodes de travail, algérienne et française, sont nulles ? En tout cas, voilà les deux présidents avertis pour leur prochain sommet : c'est la mode anglaise qui paie ! Chapeau melon et canne gentry. Un air des Beatles au-dessus d'Alger. El-Harrach transformé en Tamise. Sidi Yahia en City... Hélas, le 5-Juillet est loin de ressembler à Wembley. Et quand il pleut, il ne ressemble même pas au champ de patates de James Andrews, fermier albinos du Yorkshire ! maamarfarah20@ yahoo.fr «On en fait des histoires pour le gaz de schiste qui ne sera exploité R e D qu'en 2040 ! On sera au 8 mandat. : o t Comme c'est loin !» o h (Tata Aldjia) P MARDI 27 NOVEMBRE 2012 - 13 MOHARAM 1434 - N° 6727 - PRIX 10 DA - FAX : RÉDACTION : 021 67 06 76 - PUBLICITÉ : 021 67 06 75 - TÉL : 021 67 06 51 - 021 67 06 58 [email protected] Mardi 27 novembre 2012 - Page 2 PLaP fameuse mallette ’est une Sarl qui vient de remporter le marché pour l’acquisition par le minis- tère du Commerce de 175 mallettes destinées aux contrôleurs de la qualité. -

ECA Player Release Analysis 2010

ECA Research Facts & Key figures Coupe d’Afrique des Nations Angola, 10-31 January 2010 European Club Association Research - January 2010 Table of Contents Club origin of the players p.4 Most represented leagues p.5 Most represented clubs p.5 European clubs represented p.6 ECA clubs represented p.7 European club representation in African teams p.9 Average age within the African teams p.10 Top 3 countries in number of players by Age category p.11 Full Study of African Nations qualified for the FIFA World Cup 2010 p.12 European Club Association Research - January 2010 2 The African Cup of Nations (CAN) , is the main international football competition in Africa. It is organised by the Confédération Africaine de Football (CAF), and the first edition was held in 1957. Since 1968, it has been held every two years in January. The 27 th edition is hosted in Angola from the 10 th to 31 January 2010. Many complaints have been raised by European clubs about CAN's scheduling. As a result ECA/FIFA have signed a letter of intent which states in point D (10 July 2008): “Whenever possible, FIFA will start discussions with the African Football Confederation to consider scheduling the African cup of Nations every second time in the summer (as from 2016) and/or in any case as early as possible in January”. Currently, the qualification to the FIFA World Cup issued to qualify as well for the CAN 1. Out of 55 countries belonging to the Confédération Africaine de Football (CAF), 13 have won the trophy, leading by Egypt winning 6 times. -

190210 Appeal

DECISIONS OF THE APPEAL BOARD OF 10th FEBRUARY 2019 On February 10, 2019, the Appeal Board of Confédération Africaine de Football held a meeting in order to decide on the below appeal. Appeal of the Ismaily Sporting Club of the decision of the Inter-club Competitions and Club Licensing. The Background: The appointed match officials of match no. 96 of CL between Ismaily SC of Egypt and Club Africain of Tunisia have reported in their match reports that the home fans of Ismaily SC have been continuously throwing stones and water bottles on the assistant referee and the visiting team, specifically on the 86th minute while Club Africain’s team was attempting to take a corner kick. After continuous failed attempts to restart the play, it was decided to call off the match and both teams and match officials were escorted to the dressing rooms by the security personnel. Decision of the Organizing Committee for Inter-club Competitions and Club Licensing: Referring to the Regulations of the Competition, and, in particular to Chapter XII article 3; Chapter XI article 13 and Chapter XI article 18, the Organizing Committee for Inter-club Competitions and Club Licensing has decided, on the 23rd January 2019 the elimination of Ismaily SC from the Total CAF Champions League 2018/2019 and that the overall results of the matches in which the team participated in are cancelled without prejudice to other sanctions that may be imposed by CAF Disciplinary Board. The Appeal On 24th January 2019 the Ismaily Sporting Club has appealed the decision of the Organizing Committee for Inter-club Competitions and Club Licensing. -

15Ème Edition De La Coupe De La Confédération Total De La CAF 15Th

Tour Préliminaire/ Preliminary Round 1 / 16èmes de finale / 1/16th nal Win. 1&2 vs Supersport (RSA) 1 Atletico Petroleos (ANG) vs Master Security (MAL) 45 15ème Edition de la Coupe 2 Master Security (MAL) vs Atletico Petroleos (ANG) 46 Supersport (RSA) vs Win. 1&2 de la Confédération Total de la CAF 3 Young Bualoes (SWA) vs Capetown City (RSA) 47 Win. 5&6 vs Win. 3&4 4 Capetown City (RSA) vs Young Bualoes (SWA) 15th Edition of Total CAF Confederation Cup Win. 3&4 vs Win. 5&6 5 Desportivo C. Sol (MOZ) vs Galaxy FC (BOT) 48 Total CC 2018 6 Galaxy FC (BOT) vs Desportivo C. Sol (MOZ) 49 Win. 7&8 vs Enyimba (NGA) 7 Benin vs Haa (GUI) 50 Enyimba (NGA) vs Win. 7&8 8 Haa (GUI) vs Benin Win. 11&12 vs Win. 9&10 9 APR (RWA) vs Anse Réunion (SEY) 51 Anse Réunion (SEY) vs APR (RWA) 10 52 Win. 9&10 vs Win. 11&12 11 Mali 2 vs Elwa United (LBR) Win. 15&16 vs Win. 13&14 12 Elwa United (LBR) vs Mali 2 53 Win. 13&14 vs Win. 15&16 13 AFC Leopards (KEN) vs Fosa Juniors (MAD) 54 14 Fosa Juniors (MAD) vs AFC Leopards (KEN) Win. 17&18 vs USM Alger (ALG) 55 15 Ngazi Sport (COM) vs ASPL 2000 (MRI) USM Alger (ALG) vs Win. 17&18 16 ASPL 2000 (MRI) vs Ngazi Sport (COM) 56 17 Manga Sport (GAB) vs AS Maniema (RDC) 57 Win. 19&20 vs Hilal Obied (SUD) 18 AS Maniema (RDC) vs Manga Sport (GAB) Hilal Obied (SUD) vs Win. -

CONFÉDÉRATION AFRICAINE DE FOOTBALL 12Th Edition of CAF Confederation Cup 12Ème Edition De La Coupe De La Confédération De La CAF CC 2015

CONFÉDÉRATION AFRICAINE DE FOOTBALL 12th Edition of CAF Confederation Cup 12ème Edition de la Coupe de la Confédération de la CAF CC 2015 Fixtures of the 1/8th Final of the CC 2015 / Calendrier des 1/8èmes de Finale - CC 2015 No Match Off. Name/Nom Nationality/é Ref. Neant ALIOUM Cameroon 79 Onze Créateurs vs Asec Mimosas A.I Evarist MENKOUANDE Cameroon (Mali) (Côte D'Ivoire) A.II Elvis Guy NOUPUE NGUEGOUE Cameroon 19.4.2015 17H00 R.R Antoine Max Depadoux EFFA ESSOUMA Cameroon Com El Hadji Amadou Kame Kane Senegal Ref. Joshua Opeyemi AMAO Nigeria 80 Asec Mimosas vs Onze Créateurs A.I Peter Elgam EDIBE Nigeria (Côte D'Ivoire) (Mali) A.II Abel BABA Nigeria 1, 2, 3.5.2015 R.R Abubakar AGO Nigeria Com Mohamed Guezzaz Morocco Ref. Thierry NKURUNZIZA Burundi 81 Djoliba AC de Bamako vs Accra Hearts of Oak A.I Jean Claude BIRUMUSHAHU Burundi (Mali) (Ghana) A.II Pascal NDIMUNZIGO Burundi 17, 18, 19.4.2015 R.R Pacifique NDABIHAWENIMANA Burundi Com Saidou Diori Maiga Niger Ref. Mohamed RAGAB OMARA Libya 82 Accra Hearts of Oak vs Djoliba AC de Bamako A.I Foaad mohamed EL MAGHRABI Libya (Ghana) (Mali) A.II Attia AMSAAD Libya 3.5.2015 15H00 R.R Abdallah Baesus ASHRAF Libya Com Dominic Obukadata Oneya Nigeria Ref. Bienvenu SINKO Côte D'Ivoire 83 Amel Saad Olympic Chlef vs Club Africain A.I Kouame Gabriel KANGAH Côte D'Ivoire (Algeria) (Tunisia) A.II Pelako TOURE Côte D'Ivoire 17.4.2015 18H00 R.R Abou COULIBALY Côte D'Ivoire Com Kabore Bertrand Burkina Faso Ref. -

Egyptian Football Net ©2020

ﺷﺑﻛﺔ ﻛﺭﺓ ﺍﻟﻘﺩﻡ ﺍﻟﻣﺻﺭﻳﺔ ﺩ/ ﻁﺎﺭﻕ ﺳﻌﻳﺩ - Egyptian Football Net ©2020 Egyptian Club Opponents in African Club Competitions Listing Original match result before penalty shooutout & Egyptian-Egyptian matches are counted twice. Last updated 17/7/2021 P W D L GS GA PTs GD 218 Opponent Clubs CNT 1115 555 278 282 1696 935 1388 761 Espérance "Taragy" TUN 41 18 13 10 47 33 49 14 Helal SUD 36 16 13 7 45 31 45 14 Etoile Du Sahel "Al-Najm Al-Sahily" TUN 27 8 9 10 31 32 25 -1 ASEC Mimosas ""Association Sportive des Employés de Commerce Mimosas"" CIV 24 9 8 7 28 26 26 2 Asante Kotoko SC GHA 22 7 8 7 24 24 22 0 Simba SC TAN 21 10 3 8 28 17 23 11 Mareekh SUD 20 11 5 4 29 14 27 15 Africa Sports d'Abidjan CIV 18 10 2 6 24 15 22 9 CS Sfaxien TUN 18 9 4 5 23 16 22 7 Nkana FC "Nkana Red Devils" ZAM 18 10 5 3 30 8 25 22 TP Mazembe "Englebert" RDC 18 4 6 8 13 21 14 -8 Young Africans TAN 18 11 6 1 33 8 28 25 Ahly EGY 16 2 7 7 17 23 11 -6 Club Africain TUN 16 6 3 7 21 26 15 -5 Mamelodi Sundowns FC RSA 16 7 4 5 19 17 18 2 Wydad Athletic Club "WAC" Casablanca MOR 15 8 4 3 25 15 20 10 Ahly Tripoli LBA 14 5 5 4 15 11 15 4 Enyimba NGA 14 9 2 3 22 11 20 11 Raja Club Athletic "RCA" MOR 14 4 6 4 12 14 14 -2 AS Vita Club RDC 12 4 3 5 12 14 11 -2 Canon Yaoundé CAM 12 6 1 5 17 11 13 6 Jeunesse Sportive de Kabylie "JS Kabylie" "JE Tizi-Ouzou” "Shabibat El-Qabael" ALG 12 3 4 5 11 12 10 -1 Rangers International FC "Enugu Rangers" NGA 12 5 2 5 20 17 12 3 Gor Mahia FC KEN 11 6 3 2 21 9 15 12 Saint George SC ETH 11 3 5 3 13 11 11 2 Zamalek EGY 11 6 4 1 6 5 16 1 A.P.R. -

Confédération Africaine De Football

Confédération africaine de football La confédération africaine de football , également désignée sous l'acronyme CAF, est l'organisme qui regroupe, sous l'égide de la Confédération FIFA, les fédérations de football du continent africain. africaine de football Il a fallu attendre 1956 pour que les quatre pays africains membres de la FIFA (Égypte, Soudan, Afrique du Sud et Éthiopie) s'entendent pour créer une confédération africaine et pour organiser une compétition continentale. Les statuts ont été acceptés par la FIFA en juin 10 février 1957, malgré le refus de l'Afrique du Sud de se présenter 4 mois auparavant à la première compétition continentale au Soudan, pour ne pas à avoir à présenter une équipe multi-raciale. La principale compétition organisée par la CAF est la Coupe d'Afrique des nations (CAN), mais elle organise aussi la Ligue des champions de la CAF et décerne le Ballon d'or africain, équivalent du célèbre Ballon d'or, mais uniquement réservé aux joueurs africains. Logo de la CAF Sommaire Présidents de la Confédération africaine de football Sponsoring Organisation de compétitions Palmarès des grandes compétitions Sélections nationales Sigle CAF Compétitions continentales Sport(s) Football Qualifications pour les compétitions de la FIFA représenté(s) Qualifications pour la Coupe du monde Création 10 février 1957 Qualifications pour la Coupe du monde féminine Qualifications pour la Coupe des Confédérations Président Ahmad Ahmad Siège Ville du 6 Octobre Classement des nations de la FIFA (Égypte) Clubs Compétitions continentales