A Guide to Public Housing Repositioning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Issues Facing Somali Refugees in Minneapolis, MN MPP

Housing Issues Facing Somali Refugees in Minneapolis, MN MPP Professional Paper In Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Public Policy Degree Requirements The Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs The University of Minnesota Jeffrey D. Dischinger December 15, 2009 _____________________________ __________ Assistant Professor Ryan Allen Date Signature of Paper Supervisor, certifying successful completion of oral presentation _____________________________ __________ Assistant Professor Ryan Allen Date Signature of Paper Supervisor, certifying successful completion of professional paper _____________________________ __________ Professor Edward G. Goetz Date Signature of Second Committee Member, certifying successful completion of professional paper Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature Review 3 3. Background and Demographics of Somalis in Minneapolis 7 4. Provider Interviews 18 5. Community Organizations 23 6. Recommendations 26 1. Introduction Somali immigrants face many obstacles when finding housing that suits their needs and more can be done to improve their housing conditions and options. Minnesota is home to the largest Somali population in the United States and most of them live in the Minneapolis area. As a matter of fact, more than half of the Somalis coming to the United States settle in Minnesota with the majority of these living in the Twin Cities. Of these immigrants, many are refugees that came from horrific conditions living in refugee camps due to an unstable central government in Somalia. Since 1991, Somalia has been split into four separate areas and political persecution a constant fear of many Somalis. Many Somalis have died due to the ongoing conflict between political beliefs and many survivors have fled to refugee camps where they live in poor conditions waiting and hoping that the government will eventually stabilize. -

What Affordable Housing Programs and Initiatives

WHAT AFFORDABLE HOUSING PROGRAMS AND INITIATIVES DOES THE DISTRICT OFFER? DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT: • Inclusionary Zoning Affordable Housing Program (IZ) sets aside a percentage of affordable rental or for-sale units in new residential development projects of 10 or more units as well as rehabilitation projects that are expanding an existing building by 50 percent or more. Households interested in purchasing or leasing an IZ home must take the IZ orientation class with one of DHCD partner community-based organizations and complete the online registration form. For more information, please visit the following link: www.dhcd.dc.gov/service/inclusionary-zoning-affordable-housing-program • The Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) is a special revenue fund administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development. The HPTF provides funding for the production and preservation of homes that are affordable to low-income households in the District in a wide variety of ways. The primary use of the fund is as “gap financing” that enables housing projects to have sufficient financing to provide affordable housing. The fund also provides other forms of assistance including: - pre-development loans to assist nonprofit housing developers in getting low income housing projects funded; - financing for site acquisition to provide locations to build affordable housing; - funding for the rehabilitation of single family homes. Since 2001, the HPTF has helped produce over 9,000 affordable homes for low income District residents. For more information, please visit the following link: https://dhcd.dc.gov/page/housing-production-trust-fund • The Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) provides interest-free loans and closing cost assistance to qualified applicants to purchase single-family houses, condominiums, or cooperative units. -

Public Housing

On 12 June 2009, Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture convened a day-long policy and design workshop with students and faculty to investigate the need and the potential for public housing in the United States. The financial crisis added urgency to this effort to reinvigorate a long-dormant national conversation about publicPUBLIC housing, which remains the subject of unjust stigmas and unjustified pessimism. Oriented toward reframing the issue by imagining new possi- bilities,HOUSING: the workshop explored diverse combinations of architecture and urban policy that acknowledged the responsibilitiesA of Ngovernmentew and the limits of the private markets. Principles were discussed, ideas wereC tested,onversation and scenarios were proposed. These were distributed along a typical regional cross-section, or transect, representing a wide range of settlement patterns in the United States. The transect was broken down into five sectors: Urban Core, Urban Ring, Suburban, Exurban, and Rural. Participants were asked to develop ideas within these sectors, taking into account the contents of an informational dossier that was provided in advance. The dossier laid out five simple propositions, as follows: 1 Public housing exists. Even today, after decades of subsidized private homeownership, publicly owned rental housing forms a small but important portion of the housing stock and of the cultural fabric nationwide. 2 Genuinely public housing is needed now more than ever, especially in the aftermath of a mortgage foreclosure crisis and increasingly in nonurban PUBLIC areas. 3 Public infrastructure also exists, though mainly in the form of transportation and water utilities. HOUSING: 4 Public infrastructure is also needed. -

A Vision of Zion: Rendering Shows How Erased Black Cemetery Space

ERASED A vision of Zion: Rendering shows how erased Black cemetery space could be revitalized Architects have visualized what the space could look like, if given the opportunity to restore the area. Emerald Morrow | Published: 6:21 PM EDT September 18, 2020 TAMPA, Fla. — More than a year after a whistleblower led archaeologists to hundreds of graves from a segregation- era African American cemetery underneath a public housing development and two neighboring businesses in Tampa, architects have visualized what the space could look like, if given the opportunity to restore the area. Tampa Housing Authority Chief Operating Officer Leroy Moore said architects presented the rendering as an early visioning concept. While he reiterated it is not a final design, he said THA hopes to incorporate the land that comprises Zion Cemetery into the larger redevelopment proposal of Robles Park Village. In 2019, a Tampa Bay Times investigation revealed that hundreds of graves from Zion Cemetery were missing and suggested they could be underneath Robles Park Village, a public housing apartment complex located off N. Florida Avenue in Tampa. Ground-penetrating radar and physical archaeological digs later confirmed the presence of coffins underground. Radar images also confirmed graves on an adjacent towing lot and a property owned by local businessman Richard Gonzmart. In total, archaeologists detected nearly 300 graves from the cemetery. Since then, the Tampa Housing Authority formed a committee comprising housing authority leaders, residents and leaders from Robles Park, the NAACP and the city of Tampa. Archaeologists who worked on the investigation as well as lawmakers are also part of the group. -

Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority (FCRHA) and Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD)

Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority (FCRHA) and Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) Strategic Plan for FY 2021 Adopted March 5, 2020 http://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/housing/data/strategic-plan A publication of Fairfax County Fairfax County is committed to a policy of nondiscrimination in all County programs, services and activities and will provide reasonable accommodations upon request. Please call 703.246.5101 or TTY 711. Who’s Who Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority Commissioners (As of February 2020) Robert H. Schwaninger (Mason District), Chairman C. Melissa Jonas (Dranesville District), Vice-Chairman Matthew Bell (Mount Vernon District) Christopher Craig (Braddock District) Kenneth G. Feng (Springfield District) Lenore Kelly (Sully District) Richard Kennedy (Hunter Mill District) Albert J. McAloon (Lee District) Ezra Rosser (At-Large) Rod Solomon (Providence District) Sharisse Yerby (At-Large) Department of Housing and Community Development Thomas Fleetwood, Director Amy Ginger, Deputy Director, Operations Teresa Lepe, Deputy Director, Real Estate, Finance and Development * * * * * Seema Ajrawat, Director, Financial Management and Peggy Gregory, Director, Rental Assistance Information Systems and Services Margaret Johnson, Director, Rental Housing Judith Cabelli, Director, Affordable Housing Development Ahmed Rayyan, Director, Design, Development and Construction Marta Cruz, Director of Administration Vincent Rogers, Director, Policy and Compliance Carol Erhard, Director, Homeownership/Relocation -

The Impact of Affordable Housing on Communities and Households

Discussion Paper The Impact of Affordable Housing on Communities and Households Spencer Agnew Graduate Student University of Minnesota, Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs Research and Evaluation Unit Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Does Affordable Housing Impact Surrounding Property Values? .................... 5 Chapter 2: Does Affordable Housing Impact Neighborhood Crime? .............................. 10 Chapter 3: Does Affordable Housing Impact Health Outcomes? ..................................... 14 Chapter 4: Does Affordable Housing Impact Education Outcomes? ............................... 19 Chapter 5: Does Affordable Housing Impact Wealth Accumulation, Work, and Public Service Dependence? ........................................................................................................ 24 2 Executive Summary Minnesota Housing finances and advances affordable housing opportunities for low and moderate income Minnesotans to enhance quality of life and foster strong communities. Overview Affordable housing organizations are concerned primarily with helping as many low and moderate income households as possible achieve decent, affordable housing. But housing units do not exist in a vacuum; they affect the neighborhoods they are located in, as well as the lives of their residents. The mission statement of Minnesota Housing (stated above) reiterates the connections between housing, community, and quality -

Emergency Housing & Services Quick Referral List

EMERGENCY HOUSING & SERVICES QUICK REFERRAL LIST 2014-2015 Delaware Affordable Housing Services Directory If you have no financial resources and are in need of immediate help for emergency housing or housing-related services, the following agencies may be able to assist you. Delaware Helpline 1-800-464-4357 For Most Emergencies: Delaware State Service Centers This Directory, Page 13 Emergency Shelters & This Directory Pages 80 - 91 Transitional Housing Delaware State Service Centers This Directory, Page 13 Emergency Home Heating Fuel Wilmington: (302) 654-9295 Catholic Charities Dover: (302) 674-1782 Assistance Georgetown: (302) 856-6310 Emergency Home Dover, City of (302) 736-7175 Weatherization, Repairs New Castle: (302) 498-0454 First State Community Action Agency Dover: (302) 674-1355 Georgetown: (302) 856-7761 Inter-Neighborhood Foundation (302) 429-0333 Wilmington Kent County Levy Court, (302) 744-2480 Department of Planning Services Lutheran Community Services (302) 654-8886 (N.C.C., Elderly and Disabled only) Neighborhood House, Wilmington (302) 652-3928 Newark Senior Center (302) 737-2336 New Castle County Department of (302) 395-5618 Community Services (Seniors) Catholic Charities - Basic Needs Emergency Financial Assistance Wilmington (302) 654-9295 (Security Deposit, Mortgage Payment, Dover (302) 674-1600 Small Funds) Georgetown (302) 856-9578 F.A.I.T.H. Center, Inc. (N.C.C.) (302) 654-4550 Emergency Foreclosure Assistance: Lutheran Community Services (N.C.C.) (302) 654-8886 www.DelawareHomeownerRelief.com (Qualifying Individuals) Salvation Army - Wilmington (302) 472-0700 Housing Counselors, Page 18 Dover (302) 678-9551 Seaford (302) 628-2020 Attorney General’s Foreclosure West End Neighborhood House Hotline: 800-220-5424 (302) 658-4171 (Statewide) Security Deposit Loan Program Dept. -

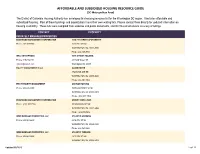

AFFORDABLE and SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area)

AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) The District of Columbia Housing Authority has developed this housing resource list for the Washington DC region. It includes affordable and subsidized housing. Most of these buildings and organizations have their own waiting lists. Please contact them directly for updated information on housing availability. These lists were compiled from websites and public documents, and DCHA cannot ensure accuracy of listings. CONTACT PROPERTY PRIVATELY MANAGED PROPERTIES EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION 1330 7TH STREET APARTMENTS Phone: 202-387-7558 1330 7TH ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3565 Phone: 202-387-7558 WEIL ENTERPRISES 54TH STREET HOUSING Phone: 919-734-1111 431 54th Street, SE [email protected] Washington, DC 20019 EQUITY MANAGEMENT II, LLC ALLEN HOUSE 3760 MINN AVE NE WASHINGTON, DC 20019-2600 Phone: 202-397-1862 FIRST PRIORITY MANAGEMENT ANCHOR HOUSING Phone: 202-635-5900 1609 LAWRENCE ST NE WASHINGTON, DC 20018-3802 Phone: (202) 635-5969 EDGEWOOD MANAGEMENT CORPORATION ASBURY DWELLINGS Phone: (202) 745-7334 1616 MARION ST NW WASHINGTON, DC 20001-3468 Phone: (202)745-7434 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC GARDENS Phone: 202-561-8600 4216 4TH ST SE WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3325 Phone: 202-561-8600 WINN MANAGED PROPERTIES, LLC ATLANTIC TERRACE Phone: 202-561-8600 4319 19th ST S.E. WASHINGTON, DC 20032-3203 Updated 07/2013 1 of 17 AFFORDABLE AND SUBSIDIZED HOUSING RESOURCE GUIDE (DC Metropolitan Area) CONTACT PROPERTY Phone: 202-561-8600 HORNING BROTHERS AZEEZE BATES (Central -

Housing Allocation, Homelessness and Stock Transfer a Guide to Key Issues

Housing Allocation, Homelessness and Stock Transfer A Guide to Key Issues January 2004 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister: London Office of the Deputy Prime Minister Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone 020 7944 4400 Web site www.odpm.gov.uk Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Further copies of this publication are available from: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister Publications PO Box 236 Wetherby LS23 7NB Tel: 0870 1226 236 Fax: 0870 1226 237 Textphone: 0870 1207 405 Email: [email protected] or online via the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister’s web site. Printed in Great Britain on material containing 75% post-consumer waste and 25% ECF pulp. January 2004 Product code: 03HC01808 Acknowledgements We would like to express our thanks to Hal Pawson of Heriot-Watt University and to David Mullins and Rob Rowlands of Birmingham University for producing the research findings on which this Guide is based. We are also extremely grateful to the case study interviewees who participated in the research from both housing authorities and housing associations for providing examples and agreeing to their use in this Guidance. We also acknowledge assistance from Michele Walsh, Housing Corporation and Gill Green and Roger Jarman, Audit Commission, as well as to internal policy colleagues in ODPM, in providing access to further good practice examples and commenting on earlier drafts of the Guide. -

EWISH Vo1ce HERALD

- ,- The 1EWISH Vo1CE HERALD /'f) ,~X{b1)1 {\ ~ SERVING RHODE ISLAND AND SOUTHEASTERN MASSACHUSETTS V C> :,I 18 Nisan 5773 March 29, 2013 Obama gains political capital President asserts that political leaders require a push BY RON KAMPEAS The question now is whether Obama has the means or the WASHINGTON (JTA) - For will to push the Palestinians a trip that U.S. officials had and Israelis back to the nego cautioned was not about get tiating table. ting "deliverables," President U.S. Secretary of State John Obama's apparent success Kerry, who stayed behind during his Middle East trip to follow up with Israeli at getting Israel and Turkey Prime Minister Benjamin to reconcile has raised some Netanyahu's team on what hopes for a breakthrough on happens next, made clear another front: Israeli-Pales tinian negotiations. GAINING I 32 Survivors' testimony Rick Recht 'rocks' in concert. New technology captures memories BY EDMON J. RODMAN In the offices of the Univer Rock star Rick Recht to perform sity of Southern California's LOS ANGELES (JTA) - In a Institute for Creative Technol dark glass building here, Ho ogies, Gutter - who, as a teen in free concert locaust survivor Pinchas Gut ager - had survived Majdanek, ter shows that his memory is Alliance hosts a Jewish rock star'for audiences ofall ages the German Nazi concentra cr ystal clear and his voice is tion camp on the outskirts of BY KARA MARZIALI Recht, who has been compared to James Taylor strong. His responses seem a Lublin, Poland, sounds and [email protected] for his soulfulness and folksy flavor and Bono for bit delayed - not that different looks very much alive. -

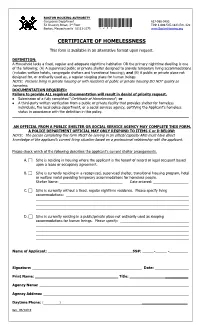

Homelessness-Priority-Certificate.Pdf

BOSTON HOUSING AUTHORITY Occupancy Department 617-988-3400 52 Chauncy Street, 3rd Floor TDD 1-800-545-1833 Ext. 420 Boston, Massachusetts 02111-2375 !255=-==! www.BostonHousing.org CERTIFICATE OF HOMELESSNESS This form is available in an alternative format upon request. DEFINITION: A Household lacks a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime habitation OR the primary nighttime dwelling is one of the following; (A) A supervised public or private shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations (includes welfare hotels, congregate shelters and transitional housing); and (B) A public or private place not designed for, or ordinarily used as, a regular sleeping place for human beings. NOTE: Persons living in private housing or with residents of public or private housing DO NOT qualify as homeless. DOCUMENTATION REQUIRED: Failure to provide ALL required documentation will result in denial of priority request. Submission of a fully completed “Certificate of Homelessness”; or A third-party written verification from a public or private facility that provides shelter for homeless individuals, the local police department, or a social services agency, certifying the Applicant's homeless status in accordance with the definition in this policy. AN OFFICIAL FROM A PUBLIC SHELTER OR SOCIAL SERVICE AGENCY MAY COMPLETE THIS FORM. A POLICE DEPARTMENT OFFICIAL MAY ONLY RESPOND TO ITEMS C or D BELOW: NOTE: The person completing this form MUST be serving in an official capacity AND must have direct knowledge of the applicant's current living situation based on a professional relationship with the applicant. Please check which of the following describes the applicant's current shelter arrangements. -

Affordable Housing

Consolidated Plan EAST WENATCHEE 1 OMB Control No: 2506-0117 (exp. 07/31/2015) Executive Summary ES-05 Executive Summary - 24 CFR 91.200(c), 91.220(b) 1. Introduction The City of East Wenatchee is located in Douglas County, Washington. East Wenatchee is on the east side of the Columbia River across from the City of Wenatchee which is located in Chelan County. Interconnecting transportation routes, regional recreation facilities, employment, housing, and community settlement patterns link both cities with Douglas County and Chelan County socially and economically. East Wenatchee and Wenatchee, serve as the economic and population hub of the two- county region. East Wenatchee is an entitlement community under Title 1 of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 and is eligible to receive Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program funds annually from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).The cities of Wenatchee and East Wenatchee were granted entitlement status. Each city separately administers their own CDBG programs. East Wenatchee’s CDBG program fiscal year is October 1 through September 30. This 2015 to 2019 Consolidated Plan for Housing and Community Development provides the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) with information on the City of East Wenatchee’s intended use of HUD's Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) funding program. The City allocates the annual funding from this program to public, private or non-profit parties consistent with HUD program goals and requirements.