A-Dzukic.Vp:Corelventura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rivers and Lakes in Serbia

NATIONAL TOURISM ORGANISATION OF SERBIA Čika Ljubina 8, 11000 Belgrade Phone: +381 11 6557 100 Rivers and Lakes Fax: +381 11 2626 767 E-mail: [email protected] www.serbia.travel Tourist Information Centre and Souvenir Shop Tel : +381 11 6557 127 in Serbia E-mail: [email protected] NATIONAL TOURISM ORGANISATION OF SERBIA www.serbia.travel Rivers and Lakes in Serbia PALIĆ LAKE BELA CRKVA LAKES LAKE OF BOR SILVER LAKE GAZIVODE LAKE VLASINA LAKE LAKES OF THE UVAC RIVER LIM RIVER DRINA RIVER SAVA RIVER ADA CIGANLIJA LAKE BELGRADE DANUBE RIVER TIMOK RIVER NIŠAVA RIVER IBAR RIVER WESTERN MORAVA RIVER SOUTHERN MORAVA RIVER GREAT MORAVA RIVER TISA RIVER MORE RIVERS AND LAKES International Border Monastery Provincial Border UNESKO Cultural Site Settlement Signs Castle, Medieval Town Archeological Site Rivers and Lakes Roman Emperors Route Highway (pay toll, enterance) Spa, Air Spa One-lane Highway Rural tourism Regional Road Rafting International Border Crossing Fishing Area Airport Camp Tourist Port Bicycle trail “A river could be an ocean, if it doubled up – it has in itself so much enormous, eternal water ...” Miroslav Antić - serbian poet Photo-poetry on the rivers and lakes of Serbia There is a poetic image saying that the wide lowland of The famous Viennese waltz The Blue Danube by Johann Vojvodina in the north of Serbia reminds us of a sea during Baptist Strauss, Jr. is known to have been composed exactly the night, under the splendor of the stars. There really used to on his journey down the Danube, the river that connects 10 be the Pannonian Sea, but had flowed away a long time ago. -

Danube Ebook

DANUBE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Claudio Magris | 432 pages | 03 Nov 2016 | Vintage Publishing | 9781784871314 | English | London, United Kingdom Danube PDF Book This article is about the river. Paris: Mouton. Ordered from the source to the mouth they are:. A look upstream from the Donauinsel in Vienna, Austria during an unusually cold winter February Date of experience: August Date of experience: May Some fishermen are still active at certain points on the river, and the Danube Delta still has an important industry. Britannica Quiz. Black Sea. Go there early in the morning while birds are still sleeping, take time to stroll across channels, eat in family run business, it is an experience you cannot find anywhere else. Viking Egypt Ships. Find A Cruise. Archived PDF from the original on 3 August Danube Waltz Passau to Budapest. Shore Excursions All ashore for easy trips straight from port. My Trip. But Dobruja it is not only Romania, Dobruja is also in Bulgaria, across the border are places as beautiful as here. My Viking Journey. Also , you can eat good and fresh fish! Published on March 3, Liberty Bridge. Vatafu-Lunghulet Nature Reserve. Restaurants near Danube Delta: 8. Donaw e. The Danube river basin is home to fish species such as pike , zander , huchen , Wels catfish , burbot and tench. However, some of the river's resources have been managed in an environmentally unsustainable manner in the past, leading to damage by pollution, alterations to the channel and major infrastructure development, including large hydropower dams. Especially the parts through Germany and Austria are very popular, which makes it one of the 10 most popular bike trails in Germany. -

Genetic Variation Among Various Populations of Spadefoot Toads (Pelobates Syriacus, Boettger, 1869) at Breeding Sites in Northern Israel

Advances in Biological Chemistry, 2013, 3, 440-447 ABC http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/abc.2013.35047 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/abc/) Genetic Variation among various populations of spadefoot toads (Pelobates syriacus, Boettger, 1869) at breeding sites in northern Israel Gad Degani School of Science and Technology, Tel Hai Academic College, Upper Galilee, Israel Email: [email protected] Received 1 August 2013; revised 9 September 2013; accepted 21 September 2013 Copyright © 2013 Gad Degani. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION A genetic study was carried out on spadefoot toads Spadefoot toads (Pelobates syriacus) are distributed in: (Pelobates syriacus) from habitats of various locations Azerbaijan (syriacus), Bulgaria (balcanicus), Greece and altitudes in northern Israel. Cytochrome b and (balcanicus), Iran (syriacus), Iraq (syriacus), Israel 12S were amplified by PCR for the analysis of genetic (syriacus), Lebanon (syriacus), Romania (balcanicus), variation based on five DNA polymorphisms and for Russia (syriacus), Syria (syriacus) and Turkey (syriacus). RAPD PCR. The nucleotide sequences of the mito- They belong to Pelobatidae, with only one genus, Pelo- chondrial DNA fragments were determined from a bates, which contains four species [1-3]. Dzukic et al. [3] 460 bp clone of cytochrome b and a 380 bp clone of reported that the distribution range of P. syriacus in the 12S (GenBank accession numbers, FJ595199-FJ59- Balkans is much larger than the previously known, rather 5203). No genetic variation was found among the compact but disjunctive. -

BULGARIA and HUNGARY in the FIRST WORLD WAR: a VIEW from the 21ST CENTURY 21St -Century Studies in Humanities

BULGARIA AND HUNGARY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY 21st -Century Studies in Humanities Editor: Pál Fodor Research Centre for the Humanities Budapest–Sofia, 2020 BULGARIA AND HUNGARY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR: A VIEW FROM THE 21ST CENTURY Editors GÁBOR DEMETER CSABA KATONA PENKA PEYKOVSKA Research Centre for the Humanities Budapest–Sofia, 2020 Technical editor: Judit Lakatos Language editor: David Robert Evans Translated by: Jason Vincz, Bálint Radó, Péter Szőnyi, and Gábor Demeter Lectored by László Bíró (HAS RCH, senior research fellow) The volume was supported by theBulgarian–Hungarian History Commission and realized within the framework of the project entitled “Peripheries of Empires and Nation States in the 17th–20th Century Central and Southeast Europe. Power, Institutions, Society, Adaptation”. Supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences NKFI-EPR K 113004, East-Central European Nationalisms During the First World War NKFI FK 128 978 Knowledge, Lanscape, Nation and Empire ISBN: 978-963-416-198-1 (Institute of History – Research Center for the Humanities) ISBN: 978-954-2903-36-9 (Institute for Historical Studies – BAS) HU ISSN 2630-8827 Cover: “A Momentary View of Europe”. German caricature propaganda map, 1915. Published by the Research Centre for the Humanities Responsible editor: Pál Fodor Prepress preparation: Institute of History, RCH, Research Assistance Team Leader: Éva Kovács Cover design: Bence Marafkó Page layout: Bence Marafkó Printed in Hungary by Prime Rate Kft., Budapest CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................... 9 Zoltán Oszkár Szőts and Gábor Demeter THE CAUSES OF THE OUTBREAK OF WORLD WAR I AND THEIR REPRESENTATION IN SERBIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY .................................. 25 Krisztián Csaplár-Degovics ISTVÁN TISZA’S POLICY TOWARDS THE GERMAN ALLIANCE AND AGAINST GERMAN INFLUENCE IN THE YEARS OF THE GREAT WAR................................ -

Pandion Wild Tours

PANDION Wild Tours & Pelican Birding Lodge WILDLIFE HOLIDAYS IN BULGARIA, GREECE AND ROMANIA 2017 TOUR CALENDAR CONTENT Dear wildlife lovers, PANDION Wild Tours we will be really happy to take you on BIRDING TOURS a virtual journey to Bulgaria using as st th a vehicle this catalogue of ours. 21 – 29 Jan. 2017 Winter tour in Bulgaria..................2 Our tour agency, “Pandion Wild Tours”, 21 st April – 2nd May 2017 Spring birding tour has endeavoured for already 23 years to welcome Bulgaria and Greece.......................5 nature lovers from almost all European countries, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, USA, Canada 26th May – 4th June 2017 Spring Birding in Bulgaria............8 and Japan. We are the oldest and most experienced 27th May – 3th June 2017 Wallcreeper & company for wildlife touring in Bulgaria. Vultures – Bulgaria.......................11 Bulgaria is a little country but there is no other like it in Europe: with such a great biodiversity within its small area! More than 250 en- 2nd – 9th Sept. 2017 Autumn Birding in Bulgaria........13 demic species of plants exist in Bulgaria along with many more rare and beautiful European ones. A very rich bird fauna, with some of the BUTTERFLY TOURS rarest representatives of European birds. In autumn, during migration, 10th – 18th June 2017 June Butterfly tour – Bulgaria.....15 you may enjoy really unforgettable sights watching scores of thousands th th of migrating large birds of prey, storks and pelicans, hundreds of thou- 8 – 15 July 2017 July Butterfly tour – Bulgaria......18 sands of smaller migratory birds. And all of them following for millennia BOTANICAL TOURS one and the same route called from ancient times Via Pontica flyway. -

Torrential Floods and Town and Country Planning in Serbia

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 12, 23–35, 2012 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/12/23/2012/ Natural Hazards doi:10.5194/nhess-12-23-2012 and Earth © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. System Sciences Torrential floods and town and country planning in Serbia R. Ristic´1, S. Kostadinov1, B. Abolmasov2, S. Dragicevi´ c´3, G. Trivan4, B. Radic´1, M. Trifunovic´5, and Z. Radosavljevic´6 1University of Belgrade Faculty of Forestry, Department for Ecological Engineering in Protection of Soil and Water Resources Kneza Višeslava 1, 11030 Belgrade, Serbia 2University of Belgrade Faculty of Mining and Geology, Belgrade, Serbia 3University of Belgrade Faculty of Geography, Belgrade, Serbia 4Secretariat for Environmental Protection of Belgrade City, Belgrade, Serbia 5Institute of Transport and Traffic Engineering-Center for Research and Designing, Belgrade, Serbia 6Republic Agency for Spatial Planning, Belgrade, Serbia Correspondence to: R. Ristic´ ([email protected]) Received: 12 August 2011 – Revised: 8 November 2011 – Accepted: 14 November 2011 – Published: 2 January 2012 Abstract. Torrential floods are the most frequent natu- pogenic extreme phenomena all around the world makes us ral catastrophic events in Serbia, causing the loss of hu- pay more attention to their environmental and economic im- man lives and huge material damage, both in urban and ru- pacts (Guzzetti et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2006; Lerner, ral areas. The analysis of the intra-annual distribution of 2007). Floods, in all their various forms, are the most fre- maximal discharges aided in noticing that torrential floods quent natural catastrophic events that occur throughout the have a seasonal character. -

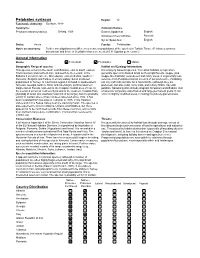

Species Summary

Pelobates syriacus Region: 10 Taxonomic Authority: Boettger, 1889 Synonyms: Common Names: Pelobates transcaucasicus Delwig, 1928 Eastern Spadefoot English Siriiskaya Chesnochnitsa Russian Syrian Spadefoot English Order: Anura Family: Pelobatidae Notes on taxonomy: Further investigations into differences between populations of the species in Turkish Thrace (Pelobates syriacus balcanicus) and those of Seydişhir vilayet are needed (İ.H. Ugurtas pers. comm.). General Information Biome Terrestrial Freshwater Marine Geographic Range of species: Habitat and Ecology Information: This species occurs in the south-east Balkans, east to south-eastern It is a largely fossorial species. Terrestrial habitats occupied are Transcaucasia and northern Iran, and south to the Levant. In the generally open uncultivated lands such as light forests, steppe (and Balkans it occurs in Greece, Macedomia, eastern Serbia, southern steppe-like habitats), semi-desert and rocky areas. It is generally less Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey. It occurs widely, but in scattered selective than Pelobates fuscus in terms of soil preference, inhabiting populations in Turkey. In Caucasian region it is found in southeastern not only soft soils suitable for a fossorial life (although they are Armenia, Georgia north to Tbilisi and Azerbaijan, north to southern preferred), but also solid, rocky soils, particularly friable clay with Daghestan in Russia, and east to the Caspian coastal area of Iran. In pebbles. Spawning sites include stagnant temporary waterbodies; river the Levant it occurs in northern Syria and in the southern Coastal Plain or lakeside temporary waterbodies and large permanent pools. It can [Ashdod] of Israel (the southernmost limit of its range), but it is probably occur in slightly modified areas, including intensively grazed areas. -

Helminth Parasites of the Eastern Spadefoot Toad, Pelobates Syriacus (Pelobatidae), from Turkey

Turk J Zool 34 (2010) 311-319 © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/zoo-0810-2 Helminth parasites of the eastern spadefoot toad, Pelobates syriacus (Pelobatidae), from Turkey Hikmet S. YILDIRIMHAN1,*, Charles R. BURSEY2 1Uludağ University, Science and Literature Faculty, Department of Biology, 16059, Bursa - TURKEY 2Department of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, Shenango Campus, Sharon, Pennsylvania 16146 - USA Received: 07.10.2008 Abstract: Ninety-one eastern spadefoot toads, Pelobates syriacus, were collected from 3 localities in Turkey between 1993 and 2003 and examined for helminths. One species of Monogenea (Polystoma sp.) and 3 species of Nematoda (Aplectana brumpti, Oxysomatium brevicaudatum, Skrjabinelazia taurica) were found. Pelobates syriacus represents a new host record for Polystoma sp. and S. taurica. Key words: Monogenea, Nematoda, eastern spadefoot toads, Pelobates syriacus, Turkey Türkiye’den toplanan toprak kurbağası (Pelobates syriacus)’nın (Pelobatidae) helmint parazitleri Özet: 1993-2003 yılları arasında Türkiye’den 3 değişik yerden 91 toprak kurbağası helmintleri belirlenmek üzere toplanmıştır. İnceleme sonucunda 4 helmint türüne rastlanmıştır. Bunlardan biri Monogenea (Polystoma sp), 3’ü (Aplectana brumpti, Oxsyomatium brevicaudatum, Skrjabinelazia taurica) Nematoda’ya aittir. Pelobates syriacus, Polystoma sp. ve S. taurica için yeni konak kaydıdır. Anahtar sözcükler: Monogen, Nematoda, toprak kurbağası, Pelobates syriacus, Türkiye Introduction reported an occurrence of Aplectana brumpti and The eastern spadefoot toad, Pelobates syriacus Yıldırımhan et al. (1997a) found Oxysomatium brevicaudatum. The purpose of this paper is to present Boettger, 1889, a fossorial species from Israel, Syria, a formal list of helminth species harbored by P. and Turkey to Transcaucasica, lives in self- syriacus. constructed burrows in loose and soft soil at elevations up to 1600 m, except during the breeding periods. -

Report on Strategic Environmental Assessment

Извештај о стратешкој процени утицаја Програмa остваривања The Energy Sector Development Strategy Републике Србије до 2025 са пројекцијама до 2030, за период 2017. до 2023, на животну средину REPORT ON STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE ENERGY SECTOR DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA BY 2025 WITH PROJECTIONS UNTIL 2030, FOR THE PERIOD 2017–2023 Report on strategic environmental assessment for the energy sector development strategy of the Republic of Serbia by 2015 with projections until 2030, for the period 2017–2023 2 Report on strategic environmental assessment for the energy sector development strategy of the Republic of Serbia by 2015 with projections until 2030, for the period 2017–2023 C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTORY NOTES..............................................................................................................4 1. STARTING POINTS FOR STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT................ 5 1.1. Overview of the subject, contents and objectives of the strategy and relationship to other documents.......................................................................................................................................5 1.1.1 Subject and contents of the Program………………………………………………………5 1.1.2 Objectives of the Program .................................................................................................. 8 1.1.3 Relationship to other documents ……………………………………………………….... 9 1.2 Overview of environmental quality and the current state of the environment.................................12 -

Directory of Azov-Black Sea Coastal Wetlands

Directory of Azov-Black Sea Coastal Wetlands Kyiv–2003 Directory of Azov-Black Sea Coastal Wetlands: Revised and updated. — Kyiv: Wetlands International, 2003. — 235 pp., 81 maps. — ISBN 90 5882 9618 Published by the Black Sea Program of Wetlands International PO Box 82, Kiev-32, 01032, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected] Editor: Gennadiy Marushevsky Editing of English text: Rosie Ounsted Lay-out: Victor Melnychuk Photos on cover: Valeriy Siokhin, Vasiliy Kostyushin The presentation of material in this report and the geographical designations employed do not imply the expres- sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of Wetlands International concerning the legal status of any coun- try, area or territory, or concerning the delimitation of its boundaries or frontiers. The publication is supported by Wetlands International through a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries of the Netherlands and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands (MATRA Fund/Programme International Nature Management) ISBN 90 5882 9618 Copyright © 2003 Wetlands International, Kyiv, Ukraine All rights reserved CONTENTS CONTENTS3 6 7 13 14 15 16 22 22 24 26 28 30 32 35 37 40 43 45 46 54 54 56 58 58 59 61 62 64 64 66 67 68 70 71 76 80 80 82 84 85 86 86 86 89 90 90 91 91 93 Contents 3 94 99 99 100 101 103 104 106 107 109 111 113 114 119 119 126 130 132 135 139 142 148 149 152 153 155 157 157 158 160 162 164 164 165 170 170 172 173 175 177 179 180 182 184 186 188 191 193 196 198 199 201 202 4 Directory of Azov-Black Sea Coastal Wetlands 203 204 207 208 209 210 212 214 214 216 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 230 232 233 Contents 5 EDITORIAL AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Directory is based on the national reports prepared for the Wetlands International project ‘The Importance of Black Sea Coastal Wetlands in Particular for Migratory Waterbirds’, sponsored by the Netherlands Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries. -

Biodiversity Assessment for Georgia

Biodiversity Assessment for Georgia Task Order under the Biodiversity & Sustainable Forestry IQC (BIOFOR) USAID C ONTRACT NUMBER: LAG-I-00-99-00014-00 SUBMITTED TO: USAID WASHINGTON E&E BUREAU, ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION SUBMITTED BY: CHEMONICS INTERNATIONAL INC. WASHINGTON, D.C. FEBRUARY 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I INTRODUCTION I-1 SECTION II STATUS OF BIODIVERSITY II-1 A. Overview II-1 B. Main Landscape Zones II-2 C. Species Diversity II-4 SECTION III STATUS OF BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION III-1 A. Protected Areas III-1 B. Conservation Outside Protected Areas III-2 SECTION IV STRATEGIC AND POLICY FRAMEWORK IV-1 A. Policy Framework IV-1 B. Legislative Framework IV-1 C. Institutional Framework IV-4 D. Internationally Supported Projects IV-7 SECTION V SUMMARY OF FINDINGS V-1 SECTION VI RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVED BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION VI-1 SECTION VII USAID/GEORGIA VII-1 A. Impact of the Program VII-1 B. Recommendations for USAID/Georgia VII-2 ANNEX A SECTIONS 117 AND 119 OF THE FOREIGN ASSISTANCE ACT A-1 ANNEX B SCOPE OF WORK B-1 ANNEX C LIST OF PERSONS CONTACTED C-1 ANNEX D LISTS OF RARE AND ENDANGERED SPECIES OF GEORGIA D-1 ANNEX E MAP OF LANDSCAPE ZONES (BIOMES) OF GEORGIA E-1 ANNEX F MAP OF PROTECTED AREAS OF GEORGIA F-1 ANNEX G PROTECTED AREAS IN GEORGIA G-1 ANNEX H GEORGIA PROTECTED AREAS DEVELOPMENT PROJECT DESIGN SUMMARY H-1 ANNEX I AGROBIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN GEORGIA (FROM GEF PDF GRANT PROPOSAL) I-1 SECTION I Introduction This biodiversity assessment for the Republic of Georgia has three interlinked objectives: · Summarizes the status of biodiversity and its conservation in Georgia; analyzes threats, identifies opportunities, and makes recommendations for the improved conservation of biodiversity. -

New Luminescence-Based Geochronology Framing the Last Two Glacial Cycles at the Southern Limit of European Pleistocene Loess in Stalać (Serbia)

GEOCHRONOMETRIA 44 (2017): 150–161 DOI 10.1515/geochr-2015-0062 Available online at http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/geochr NEW LUMINESCENCE-BASED GEOCHRONOLOGY FRAMING THE LAST TWO GLACIAL CYCLES AT THE SOUTHERN LIMIT OF EUROPEAN PLEISTOCENE LOESS IN STALAĆ (SERBIA) JANINA BÖSKEN1, NICOLE KLASEN2, CHRISTIAN ZEEDEN1, IGOR OBREHT1, SLOBODAN B MARKOVIĆ3, ULRICH HAMBACH4, 3 and FRANK LEHMKUHL1 1Department of Geography, RWTH Aachen University, Templergraben 55, D-52056 Aachen, Germany 2Institute of Geography, University of Cologne, Albertus-Magnus-Platz, D-50923 Cologne, Germany 3Laboratory for Paleoenvironmental Reconstruction, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Trg Dositeja Obradovića 2, 21000 Novi Sad, Serbia 4BayCEER & Chair of Geomorphology, University of Bayreuth, D-94450 Bayreuth, Germany Received 25 August 2016 Accepted 22 March 2017 Abstract: A new geochronology was established for the Stalać loess-paleosol sequence (LPS) in Ser- bia. The section is located in the interior of the Central Balkan region, south of the typical loess dis- tribution, in a zone of paleoclimatic shifts between continental and Mediterranean climate regimes. The sampled sequence contains four well-developed paleosol and loess layers, a crypto tephra and one visible tephra layer. Optically stimulated luminescence measurements showed a strong dependen- cy of preheat temperature on equivalent dose for one fine-grained quartz sample, which makes it un- suitable for dating. A firm chronology framing the last two glacial cycles was established using fine- grained polyminerals and the post-infrared infrared stimulated luminescence (pIR50IR290) protocol in- stead. The characteristics of dated paleosols indicate similar climatic conditions during the last inter- stadial and interglacial phases, which were different from the penultimate interglacial period.