Radial Categories and the Central Romance*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epic and Romance Essays on Medieval Literature W

EPIC AND ROMANCE ESSAYS ON MEDIEVAL LITERATURE W. P. KER PREFACE These essays are intended as a general description of some of the principal forms of narrative literature in the Middle Ages, and as a review of some of the more interesting works in each period. It is hardly necessary to say that the conclusion is one "in which nothing is concluded," and that whole tracts of literature have been barely touched on--the English metrical romances, the Middle High German poems, the ballads, Northern and Southern--which would require to be considered in any systematic treatment of this part of history. Many serious difficulties have been evaded (in Finnesburh, more particularly), and many things have been taken for granted, too easily. My apology must be that there seemed to be certain results available for criticism, apart from the more strict and scientific procedure which is required to solve the more difficult problems of Beowulf, or of the old Northern or the old French poetry. It is hoped that something may be gained by a less minute and exacting consideration of the whole field, and by an attempt to bring the more distant and dissociated parts of the subject into relation with one another, in one view. Some of these notes have been already used, in a course of three lectures at the Royal Institution, in March 1892, on "the Progress of Romance in the Middle Ages," and in lectures given at University College and elsewhere. The plot of the Dutch romance of Walewein was discussed in a paper submitted to the Folk-Lore Society two years ago, and published in the journal of the Society (Folk-Lore, vol. -

Ariosto and the Arabs: Contexts of the Orlando Furioso

ARIOSTO AND THE ARABS Contexts of the Orlando Furioso Among the most dynamic Italian literary texts The conference is funded with support from the of the sixteenth century, Ludovico Ariosto’s Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Endowment Fund and the Orlando Furioso (1532) emerged from a world scholarly programs and publications funds in the names of Myron and Sheila Gilmore, Jean-François Malle, Andrew W. Mellon, whose international horizons were rapidly Robert Lehman, Craig and Barbara Smyth, expanding. At the same time, Italy was subjected and Malcolm Hewitt Wiener to a succession of debilitating political, social, and religious crises. This interdisciplinary conference takes its point of departure in Jorge Luis Borges’ celebrated poem “Ariosto y los Arabes” (1960) in order to focus on the Muslim world as the essential ‘other’ in the Furioso. Bringing together a diverse range of scholars working on European and Near Middle Eastern Villa I Tatti history and culture, the conference will examine Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy +39 055 603 251 [email protected] Ariosto’s poem, its earlier sources, contemporary www.itatti.harvard.edu resonance, and subsequent reception within a matrix of Mediterranean connectivity from late antiquity through the medieval period, into early modernity, and beyond. Organized by Mario Casari, Monica Preti, Front Cover image: and Michael Wyatt. Dosso Dossi Melissa, c. 1518, detail Galleria Borghese Rome Back cover image: Ariosto Sīrat alf layla wa-layla Ms. M.a. VI 32, 15th-16th century, detail, -

NEW ENGLAND DRESSAGE FALL FESTIVAL September 9 / 10 / 11 / 12 / 13, 2009 ~ Saugerties NY HITS on the Hudson ~ Saugerties NY

NEW ENGLAND DRESSAGE FALL FESTIVAL September 9 / 10 / 11 / 12 / 13, 2009 ~ Saugerties NY HITS on the Hudson ~ Saugerties NY 000/0 0/Breed Sweepstakes Colt/Gelding/Stallion 0 Breed Sweepstakes Colt/Gelding/Stalion / / 1 77.700% Ellen Kvinta Palmisano / Ellen Kvinta Palmisano / Red Meranti / Kwpn C 15.0 1 Ch 2 77.300% Ellen Kvinta Palmisano / Ellen Kvinta Palmisano / Juvenal / AmWarmSoc S 16.0 2 Ch 3 77.000% Bobby Murray / Inc Pineland Farms / Rubinair / Westf G 14.3 2 Bay 4 75.600% Mary Anne Morris / Mary Anne Morris / Wakefield / Han G 15.2 3 Bay 5 75.300% Bobby Murray / Inc Pineland Farms / Delgado / Kwpn S 12.3 1 Bay 6 75.000% Bobby Murray / Inc Pineland Farms / Catapult / Kwpn G 2 Bay 000/1 1/Breed Sweepstakes Filly/Mare 0 Breed Sweepstakes Filly/Mare / / 1 79.200% Bobby Murray / Inc Pineland Farms / Utopia / Kwpn M 8 Ch 2 78.900% Silene White / Silene White / Fusion / Han M 15.0 2 Bay 3 78.300% Kendra Hansis / Kendra Hansis / Raleska / Han M 14.2 1 Bl 4 76.300% Jen Vanover / Jen Vanover / MW Donnahall / GV M 16.2 3 Bay 5 73.300% Anne Early / Anne Early / DeLucia CRF / Oldbg F 15.3 2 Bay 6 72.000% Silene White / Silene White / Shutterfly's Buzz / Oldbg F 1 Grey 000/2 2/Dressage Sweepstakes Training Level 0 Dressage Sweepstakes Training Level / / 1 75.400% Marie Louise Barrett / Leigh Dunworth / Dunant / Oldbg G 17.0 5 Bay 2 71.600% Melanie Cerny / Melanie Cerny / Prime Time MC / Oldbg G 16.2 7 Bay 3 70.000% Diane Glossman / Diane Glossman / Copacabana 29 / Han M 16.2 6 Bay 4 69.400% Nadine Schlonsok / Melanie Pai / Devotion / Oldbg -

Orlando Furioso: Pt. 2 Free Download

ORLANDO FURIOSO: PT. 2 FREE DOWNLOAD Ludovico Ariosto,Barbara Reynolds | 800 pages | 08 Dec 1977 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140443103 | English | London, United Kingdom Follow the author Save on Fiction Books Trending price is based on prices over last 90 days. Matter of FranceMatter of Britain. Ludovico Orlando Furioso: Pt. 2. Alex Ilushik rated it it was ok Mar 07, To render it as something else is to lose its structure, its purpose and its very nature. Rating Average: 4. Orlando is the Christian knight known in French and subsequently English as Roland. Translated Into English Verse from the Italian. Vivaldi crater Vivaldi Glacier. Error rating book. Mar 18, Jamie rated Orlando Furioso: Pt. 2 really liked it Shelves: because-lentfanfic-positivefantasticallife-and- deathhistorical-contextmyths-and-folklore Orlando Furioso: Pt. 2, poetry-and-artOrlando Furioso: Pt. 2viva-espanaviva-italia. Hearts and Armour Paperback Magazines. Essentially he was a writer; his lifetime's service as a courtier was a burden imposed on him by economic difficulties. A comparison the original text of Book 1, Canto 1 with various English translations is given in the following table. Published by Penguin Classics. Great Britain's Great War. In a delightful garden in which two springs are seen, Medoro escapes from a shipwreck into the arms of his beloved Angelica. NOT SO!! They come off as actual characters now in a way they didn't before. Sort by title original date published date published avg rating num ratings format. Tasso tried to combine Ariosto's freedom of invention with a more unified plot structure. Customer Orlando Furioso: Pt. -

Renaissance and Reformation, 1978-79

Sound and Silence in Ariosto's Narrative DANIEL ROLFS Ever attentive to the Renaissance ideals of balance and harmony, the poet of the Orlando Furioso, in justifying an abrupt transition from one episode of his work to another, compares his method to that of the player of an instrument, who constantly changes chord and varies tone, striving now for the flat, now for the sharp. ^ Certainly this and other similar analogies of author to musician^ well characterize much of the artistry of Ludovico Ariosto, who, like Tasso, even among major poets possesses an unusually keen ear, and who continually enhances his narrative by means of imaginative and often complex plays upon sound. The same keenness of ear, however, also enables Ariosto to enrich numerous scenes and episodes of his poem through the creation of the deepest of silences. The purpose of the present study is to examine and to illustrate the wide range of his literary techniques in each regard. While much of the poet's sensitivity to the aural can readily be observed in his similes alone, many of which contain a vivid auditory component,^ his more significant treatments of sound are of course found throughout entire passages of his work. Let us now turn to such passages, which, for the convenience of the non-speciaUst, will be cited in our discussion both in the Italian text edited by Remo Ceserani, and in the excellent English prose translation by Allan Gilbert."* In one instance, contrasting sounds, or perhaps more accurately, the trans- formation of one sound into another, even serves the implied didactic content of an episode with respect to the important theme of distin- guishing illusion from reality. -

Geoffrey of Monmouth's De Gestis Britonum and Twelfth-Century

Chapter 8 Geoffrey of Monmouth’s De gestis Britonum and Twelfth-Century Romance Françoise Le Saux Geoffrey of Monmouth’s De gestis Britonum had a long and influential after- life. The work was exploited to endow Anglo-Norman Britain with a founda- tion myth on which to build a common (though not unproblematic) political identity, giving rise to a new historiographical tradition in Latin, French, and English. At the same time, the great deeds of past British kings form a treasure house of narratives, with the figure of King Arthur at the heart of a new literary phenomenon, the Arthurian romance. The entertainment potential of the DGB is flagged up by Geoffrey of Monmouth himself in his prologue, where he sketches a context of oral tradi- tion and popular story-telling “about Arthur and the many others who suc- ceeded after the Incarnation” related “by many people as if they had been entertainingly and memorably written down”.1 The exact nature of this pre-existing narrative tradition is not specified, though the archivolt of the Porta della Peschiera of Modena Cathedral, depicting a scene where Arthur and his knights appear to be attacking a castle to free the captive Winlogee (Guinevere?), is proof of the popularity of tales of Arthur in western Europe by 1120–40.2 The huge success of the DGB therefore reinforced and reshaped an already existing tradition, and as such was instrumental in the flowering of the courtly Arthurian romances of the latter 12th century. Geoffrey of Monmouth made King Arthur enter the Latinate cultural mainstream. -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

The Narrator As Lover in Ariosto's Orlando Furioso

This is a repository copy of Beyond the story of storytelling: the Narrator as Lover in Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/88821/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Pich, F (2015) Beyond the story of storytelling: the Narrator as Lover in Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. The Italianist, 35 (3). 350 - 368. ISSN 0261-4340 https://doi.org/10.1179/0261434015Z.000000000128 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Federica Pich Beyond the story of storytelling: the Narrator as Lover in Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso Chi salirà per me, madonna, in cielo a riportarne il mio perduto ingegno? che, poi ch’usc da’ bei vostri occhi il telo che ’l cor mi fisse, ognior perdendo vegno. -

Ruggiero Transl

Francesca Caccini La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola d’Alcina Translation © 2013 Anne Graf / Selene Mills FRANCESCA CACCINI music for women’s voices, for herself and her (1587 to post-1641) pupils, and contributed to many court entertainments, but this is her only surviving ‘La Liberazione di Ruggiero dall’isola opera. d’Alcina’ (1625): The opera: ‘La liberazione di Ruggiero Commedia in musica: Prologue and 4 Scenes dall’isola d’Alcina ’ was commissioned by Florence’s Regent Archduchess, Maria Introduction, Dramatis Personae & List of Magdalena of Austria (hence her honorific Scenes, Synopsis, and Translation mention in the opera’s concluding ballet stage (the last with much help from Selene Mills): directions). It was published under her auspices for the state occasion of the visit to Anne Graf 2010 / rev. 2013 Carnival by a Polish prince, Wladislas Sigismund. It celebrates his recent victory Sources over the Turks (symbolised in the opera by the Edition by Brian Clark 2006, pub. Prima la wicked sorceress Alcina). The first Musica! 3 Hamilton St, Arbroath, DD11 5JA performance was in Florence in the Villa (http://www.primalamusica.com), with Notes Poggia Imperiale on 3 February 1625, and it therein; and separate text of the Libretto by was revived in Warsaw in 1628. Ferdinand Saracinelli; -with additional information from the article The music: Francesca set the libretto as a on Francesca Caccini by Suzanne G. Cusick ‘Balletto in Musica ’, part opera, part ballet, in ‘The New Grove Dictionary of Music and lasting about 2 hours, with music, drama and Musicians’ ed. S. Sadie 1980, 2 nd edn.2001, dance, concluding with a grand ‘Cavalry vol.4 pp775-777; Ballet’on horseback ( balletto a cavallo ) such -and from the English translation of ‘ Orlando as was popular in Florence from the mid- Furioso ’ by Guido Waldmann 1974, Oxford 1610’s onwards. -

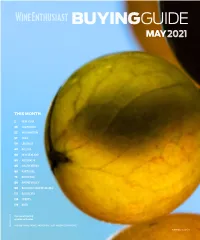

Wine Enthusiast May 2021 Buying Guide

BUYINGGUIDE MAY 2021 THIS MONTH 2 NEW YORK 25 CALIFORNIA 52 WASHINGTON 57 CHILE 59 URUGUAY 60 BOLIVIA 60 NEW ZEALAND 63 AUSTRALIA 65 SOUTH AFRICA 68 PORTUGAL 73 BORDEAUX 86 RHÔNE VALLEY 99 BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO 112 BASILICATA 116 SPIRITS 119 BEER Close up of Riesling growing on the vine FOR ADDITIONAL RATINGS AND REVIEWS, VISIT WINEMAG.COM/RATINGS SHUTTERSTOCK WINEMAG.COM | 1 BUYINGGUIDE Fox Run 2019 Silvan Riesling (Seneca Lake). For full review see page 9. Editors’ Choice. 93 abv: 12.4% Price: $20 Hermann J. Wiemer 2019 Magdalena NEW YORK Vineyard Riesling (Seneca Lake). 93 The power in seeking a sense of place Concentrated aromas of lemon oil, peach, pine and struck flint grace the nose of this single-vineyard Riesling. It’s rounded and full in feel on the palate, ieslings from New York are among the best 10 miles from the winery on the northwest filled out by juicy orchard fruit flavors yet expertly examples of the variety in the country, side of Seneca Lake, this silt loam site is one honed by zesty acidity and a delicate grip of white with those from the Finger Lakes region of the warmest in the area and consistently tea. A lemon oil tone lingers on the finish, but with leading the charge. About 1,000 acres produces a richly fruited, earthy and textured ample lift and length. —A.P. Rare planted to the grape in the area, making dry expression. abv: 12% Price: $35 it a relatively small affair, yet what it lacks in Other bottlings, like Wagner’s Caywood Hosmer 2019 Limited Release Riesling quantity, it more than makes up for in quality East or Red Newt’s Tango Oaks, are more (Cayuga Lake). -

An Introduction to the Medieval English: the Historical and Literary Context, Traces of Church and Philosophical Movements in the Literature

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 8 No. 1; February 2017 Australian International Academic Centre, Australia F l o u r is h i ng Cr ea ti v it y & L it e r ac y An Introduction to the Medieval English: The Historical and Literary Context, Traces of Church and Philosophical Movements in the Literature Esmail Zare Behtash English Language Department, Faculty of Management and Humanities, Chabahar Maritime University, Chabahar, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Seyyed Morteza Hashemi Toroujeni (Correspondence author) English Languages Department, Faculty of Management and Humanities, Chabahar Maritime University, Chabahar, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Farzane Safarzade Samani English Language Department, Faculty of Management and Humanities, Chabahar Maritime University, Chabahar, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.1p.143 Received: 19/10/2016 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.1p.143 Accepted: 23/01/2017 Abstract The Transition from Greek to medieval philosophy that speculated on religion, nature, metaphysics, human being and society was rather a rough transition in the history of English literature. Although the literature content of this age reflected more religious beliefs, the love and hate relationship of medieval philosophy that was mostly based on the Christianity with Greek civilization was exhibited clearly. The modern philosophical ideologies are the continuation of this period’s ideologies. Without a well understanding of the philosophical issues related to this age, it is not possible to understand the modern ones well. The catholic tradition as well as the religious reform against church called Protestantism was organized in this age. -

Des Lectrices De Chansons De Geste Aux Xiiie–Xve Siècles ? Jean-Baptiste Camps

Des lectrices de chansons de geste aux XIIIe–XVe siècles ? Jean-Baptiste Camps To cite this version: Jean-Baptiste Camps. Des lectrices de chansons de geste aux XIIIe–XVe siècles ?. Douchet, Sébastien; Halary, Marie-Pascale; Lefèvre, Sylvie; Moran, Patrick; Valette, Jean-René. De la pensée de l’histoire au jeu littéraire: études médiévales en l’honneur de Dominique Boutet, pp.409-426, 2019, Nouvelle bibliothèque du Moyen âge, 978-2-7453-5145-6. halshs-03018425 HAL Id: halshs-03018425 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03018425 Submitted on 30 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. DES LECTRICES DE CHANSONS DE GESTE AUX XIIIe- XVe SIÈCLES ? Lorsque l’on cherche à imaginer le public de nos chansons de geste, on tend à se former l’idée d’un public aristocratique masculin et guerrier, semblable, au fond, aux héros des textes eux-mêmes, à l’image des guerriers de Guillaume le Conquérant écoutant la Chanson de Roland avant la bataille de Hastings. Certes, les évolutions progressives du genre épique, qui rendent « au milieu du XIIIe siècle […] impossible d’écrire une chanson de geste purement féodale et guerrière »1, pourraient nuancer cette impression.