Life Challenges and the Atheistic Worldview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Beyond Death by Swami Abhedananda

Life Beyond Death Lectures of Swami Abhedananda A Great Yogi and Direct Disciple of Sri Ramakrishna Life Beyond Death – lovingly restored by The Spiritual Bee An e-book presentation by For more FREE books visit the website: www.spiritualbee.com Dear Reader, This book has been reproduced here from the Complete Works of Swami Abhedananda, Volume 4. The book is now in the public domain in India and the United States, because its original copyright has expired. “Life beyond Death” is a collection of lectures delivered by Swami Abhedananda in the United States. Unlike most books on the subject which mainly record encounters with ghosts and other kinds of paranormal activities, this book looks at the mystery from a soundly rational and scientific perspective. The lectures initially focus on providing rational arguments against the material theory of consciousness, which states that consciousness originates as a result of brain activity and therefore once death happens, consciousness also ends and so there is no such thing as a life beyond death. Later in the book, Swami Abhedananda also rallies against many dogmatic ideas present in Christian theology regarding the fate of the soul after death: such as the philosophies of eternal damnation to hell, resurrection of the physical body after death and the belief that the soul has a birth, but no death. In doing so Swami Abhedananda who cherished the deepest love and respect for Christ, as is evident in many of his other writings such as, “Was Christ a Yogi” (from the book How to be a Yogi?), was striving to place before his American audience, higher and more rational Vedantic concepts surrounding life beyond the grave, which have been thoroughly researched by the yogi’s of India over thousands of years. -

What Has Athens to Do with Mormonism?

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Student Writing Award Winners Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 12-2012 What has Athens to do with Mormonism? Benjamin Wade Harman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_stwriting Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Harman, Benjamin Wade, "What has Athens to do with Mormonism?" (2012). Arrington Student Writing Award Winners. Paper 9. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_stwriting/9 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Student Writing Award Winners by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What has Athens to do with Mormonism? Benjamin Wade Harman In his lecture, Terryl Givens presents one with a new way to approach the prophecy of Enoch that was received by Joseph Smith. Contained in this short narrative is a new, innovative conception about God that differs greatly from traditional Christianity. This notion is that of a passible deity, a God that is susceptible to feeling and emotion. It is a God who weeps, a God who is vulnerable and suffers emotional pain. God, as defined by the Christian creeds, is one who lacks passions.1 Givens, in drawing attention to the passible deity, is illuminating just a small portion of a much larger tension that exists between Mormonism and traditional Christianity. The God of Mormonism is not just a slight modification of the God of the creeds. Traditionally Christians, who now will be referred to as orthodox, have endorsed a view of deity that is more or less in line with the God of Classical Theism, or the God of the philosophers. -

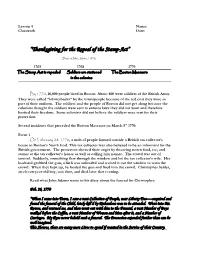

Lesson 4 Name: Classwork Date

Lesson 4 Name: Classwork Date: “Thanksgiving for the Repeal of the Stamp-Act” (Diary of John Adams, 1:316) 1765 1768 1770 The Stamp Act is repealed Soldiers are stationed The Boston Massacre in the colonies By 1770, 16,000 people lived in Boston. About 600 were soldiers of the British Army. They were called “lobsterbacks” by the townspeople because of the red coat they wore as part of their uniform. The soldiers and the people of Boston did not get along because the colonists thought the soldiers were sent to enforce laws they did not want and therefore limited their freedom. Some colonists did not believe the soldiers were sent for their protection. Several incidents that preceded the Boston Massacre on March 5th 1770: Event 1 On February 28, 1770, a mob of people formed outside a British tax collector’s house in Boston’s North End. This tax collector was also believed to be an informant for the British government. The protestors showed their anger by throwing rotten food, ice, and stones at the tax collector’s house as well as calling him names. The crowd was out of control. Suddenly, something flew through the window and hit the tax collector’s wife. Her husband grabbed the gun, which was unloaded and waived it out the window to warn the crowd. When they kept up, he loaded the gun and fired into the crowd. Christopher Seider, an eleven-year-old boy, was shot, and died later that evening. Read what John Adams wrote in his diary about the funeral for Christopher: Feb. -

Divine Utilitarianism

Liberty University DIVINE UTILITARIANISM A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Masters of Arts in Philosophical Studies By Jimmy R. Lewis January 16, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One: Introduction ……………………………...……………..……....3 Statement of the Problem…………………………….………………………….3 Statement of the Purpose…………………………….………………………….5 Statement of the Importance of the Problem…………………….……………...6 Statement of Position on the Problem………………………...…………….......7 Limitations…………………………………………….………………………...8 Development of Thesis……………………………………………….…………9 Chapter Two: What is meant by “Divine Utilitarianism”..................................11 Introduction……………………………….…………………………………….11 A Definition of God.……………………………………………………………13 Anselm’s God …………………………………………………………..14 Thomas’ God …………………………………………………………...19 A Definition of Utility .…………………………………………………………22 Augustine and the Good .……………………………………………......23 Bentham and Mill on Utility ……………………………………………25 Divine Utilitarianism in the Past .……………………………………………….28 New Divine Utilitarianism .……………………………………………………..35 Chapter Three: The Ethics of God ……………………………………………45 Divine Command Theory: A Juxtaposition .……………………………………45 What Divine Command Theory Explains ………………….…………...47 What Divine Command Theory Fails to Explain ………………………47 What Divine Utilitarianism Explains …………………………………………...50 Assessing the Juxtaposition .…………………………………………………....58 Chapter Four: Summary and Conclusion……………………………………...60 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………..64 2 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Statement of the -

Second Death! Eternal=Immortality

Eternal=Second Death! Eternal=Immortality. Heb. 9:27 And as it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment: Ps. 89:48 What man is he that liveth, and shall not see death? shall he deliver his soul from the hand of the grave? Selah. Ecc. 3:19 For that which befalleth the sons of men befalleth beasts; even one thing befalleth them: as the one dieth, so dieth the other; yea, they have all one breath; so that a man hath no preeminence above a beast: for all is vanity. 3:20 All go unto one place; all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again. 1 Kings 2:2 I go the way of all the earth: be thou strong therefore, and show thyself a man; Ps. 102:25 Of old hast thou laid the foundation of the earth: and the heavens are the work of thy hands. 102:26 They shall perish, but thou shalt endure: yea, all of them shall wax old like a garment; as a vesture shalt thou change them, and they shall be changed: Rev. 20:6 Blessed and holy is he that hath part in the first resurrection: on such the second death hath no power, but they shall be priests of God and of Christ, and shall reign with him a thousand years. It will be admitted by all that Adam was placed on probation, and that the penalty of death, absolute and irrevocable, was affixed to the violation of the command not to eat of the forbidden tree. -

Some Suggestions for Divine Command Theorists

Some Suggestions for Divine Command Theorists WILLIAM P. ALSTON I The basic idea behind a divine command theory of ethics is that what I morally ought or ought not to do is determined by what God commands me to do or avoid. This, of course, gets spelled out in different ways by different theorists. In this paper I shall not try to establish a divine command theory in any form, or even argue directly for such a theory, but I shall make some suggestions as to the way in which the theory can be made as strong as possible. More specifically I shall (1) consider how the theory could be made invul nerable to two familiar objections and (2) consider what form the theory should take so as not to fall victim to a Euthyphro-like di lemma. This will involve determining what views of God and hu man morality we must take in order to enjoy these immunities. The son of divine command theory from which I begin is the one presented in Robert M. Adams's paper, "Divine Command Meta ethics Modified Again.''1 This is not a view as to what words like 'right' and 'ought' mean. Nor is it a view as to what our concepts of moral obligation, rightness and wrongness, amount to. It is rather the claim that divine commands are constitutive of the moral status of actions. As Adams puts it, "ethical wrongness is (i.e., is identical with) the propeny of being contrary to the commands of a loving God.''2 Hence the view is immune to the objection that many per sons don't mean 'is contrary to a command of God' by 'is morally wrong'; just as the view that water is H 20 is immune to the objec- 303 William P. -

Forgetting Oblivion: the Demise of the Legislative Pardon

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Working Papers Faculty Scholarship 3-31-2011 Forgetting Oblivion: The eD mise of the Legislative Pardon Bernadette A. Meyler Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clsops_papers Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Legal History, Theory and Process Commons Recommended Citation Meyler, Bernadette A., "Forgetting Oblivion: The eD mise of the Legislative Pardon" (2011). Cornell Law Faculty Working Papers. Paper 83. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clsops_papers/83 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. * BERNADETTE MEYLER FORGETTING OBLIVION : THE DEMISE OF THE LEGISLATIVE PARDON TABLE OF CONTENTS : I INTRODUCTION ...........................................................1 II FROM KLEIN TO KNOTE ...............................................6 III OBLIVION ENTERS ENGLAND ......................................13 IV COLONIAL AND STATE OBLIVIONS ..............................27 V PRAGMATICS OF PARDONING ......................................45 VI CONCLUSION ...............................................................49 I INTRODUCTION Despite several bouts of attempted reinterpretation, -

Jewish and Western Philosophies of Law

Jewish and Western Philosophies of Law 1) Reason, Revelation, and Natural Law Maimonides, Mishne Torah, Laws of Kings, Chapter 10. Maimonides, Commentary, Ethics of the Fathers. Aquinas, Summa Theologica, selections. Marvin Fox, “Maimonides and Aquinas on Natural Law.” Yisrael LIfshits, Tifferet Yisrael, Avot Chapter 3 2) Natural Law and Noahide Law Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 57a, 57b. Jason Rosenblatt, Renaissance England’s Chief Rabbi: John Selden, selections. J. David Bleich, “Judaism and Natural Law.” Michael P. Levine, “The Role of Reason in the Ethics of Maimonides: Or Why Maimonides Could have had a Doctrine of Natural Law even if He Did Not,” The Journal of Religious Ethics, 14:2. 3) Modern Versions of Natural Law Theory John Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights, chs. II, V-XII. Robert P. George, In Defense of Natural Law, Selections. David Novak, Natural Law in Judaism, selections Russell Hittinger, The First Grace: Rediscovering the Natural Law in a Post Christian World,” selections. 4) Law and Divine Command Theory Maimonides, Book of Commandments, Principle 1. Robert Adams, Finite and Infinite Goods, selections. Robert Adams, The Virtue of Faith, selections. Comments of Nahmanides on Maimonides’ Book of Commandments, Principle 1. Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman, Kuntres Divrei Sofrim. 5) The Nature of Law: Hart vs. Dworkin H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, chs. I-V Ronald Dworkin, Taking Rights Seriously, chs. 2-4 6) Hart vs. Dworkin Halakhically Apllied Nissim of Gerondi, Derashot HaRan, Mishpat HaMelekh Menachem Loberbaum, Politics and the Limits of Law (Stanford: 2001). Isaac Halevi Herzog, 7) Law, Justice and Equity, Part I A. -

Themes of Violence in Picture Books

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 090 584 CS 201 275 AUTHOR Harris, Karen TITLE Themes of Violence in Picture Books. PUB DATE May 74 NOTE 8p.; Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the New York State English Council (24th, Binghamton, New York, May 1974) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Literature; Anti Social Behavior; *Childhood Attitudes; Childhood Interests; Children; *Childrens Books; *Illustrations; Literary Influences; *Violence IDENTIFIERS *Picture Books ABSTRACT The new realism in literature, revealing virtual extinction of literary taboos, is probably a positive development in offering to middle and high school students some topics and attitudes which more accurately reflect the realities they face. However, the younger reader should be protected more, especially from the violence illustrated in some contemporary picture books. Although texts in these books are often simple and mildly amusing, the drawings too frequently portray the real world out of control--a situation especially threatening to the young child. Sincea child is born with potential both for aggression and cruelty and for showing gentleness and compassion, his earliest literary experiences should counter popular glorification of violence with a balancing, humanizing effect. (JM) U S DEPARTMENTOP HEALTH, EDUCATION &WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EOUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HA} BEEN REPRO DuCED EXACTLY AS RECEis,ED FROM THE PERSON OR oRGAN,EATIoN ORIGIN ATING iT. POINTS OP VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE is SENT OFFiCiAl NATIONAL NSTTUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY TLH OF VIOLENCE IN PICTURE BOOKS Karen Harris Associate Professor of Library Science PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPY RIGHTED MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY Karen Harris 0 10 ERIC AND "3TIGAYZATFONS OPERATING UNDER AGREEMENTs WITH THE NATIONAL IN stautE OF EDUCATION FURTHER REPRO DuCTON OUTSIDE THE ERIC SYSTEM RE OU'RES PERMISSION OT THE COPYRIGHT (../) OWNER The Literary taboo is practically extinct. -

Kierkegaard and the Political

Kierkegaard and the Political Kierkegaard and the Political Edited by Alison Assiter and Margherita Tonon Kierkegaard and the Political, Edited by Alison Assiter and Margherita Tonon This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Alison Assiter and Margherita Tonon and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4061-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4061-3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 Chapter One The Singular Universal: One More Time 7 David Wood Chapter Two Kierkegaard, the Phantom of the Public 27 and the Sexual Politics of Crowds Christine Battersby Chapter Three Love for Neighbours: Using Kierkegaard 45 to respond to Žižek Alison Assiter Chapter Four Kierkegaard’s “Aesthetic Age” and its 63 Political Consequences Thomas Wolstenholme Chapter Five Suffering from Modernity, an Assessment 83 of the Hegelian Cure Margherita Tonon Chapter Six A Fractured Dialectic: Kierkegaard 103 and Political Ontology after Žižek Michael O’Neill Burns Bibliography 125 List of Contributors 135 Index 137 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The editors would like to thank all the participants in the conference “Kierkegaard and the Political,” from which this volume emerged. The conference was hosted by the Department of Politics, Philosophy and International Relations at the University of the West of England, Bristol, in April 2010. -

In the Hich I'l1y a Uremonition of His

"\ /~ ll ~ 1 I, L:s:tGY rl J 15, 1~35. a~u Very Reverend ~onsignori, ver (; ~ra tifying to j"'·u to know tha't your or in the clioCbC report r a J." hich er . in i'L1y a uremonition of his approaohing death, expr "is successor would be 1ear~ed, experlence~ and piou the Idbt ~a~e the account of the work dccomolisned i CarL/!, ,lith great a!''t'ection he let hiB thoue:ht • er!::..; anti expressed 1-_1... Jelf in these "ords: Clc..:uo .... ,laris q.am reI i 5 iooUB Zt:;' ~l;US est ... t.(,I.LO.C'J Nobis aunt lIlae, rea eVa.l.r.el ~ z.antur et aluntur, ne q ....18 e ive materia11 pereat. .Pauper sum, nOT) q mer d these observations he pointed out to t he Holy Fa ther 8S t ost 1. precious fruit and the most fragrant flower of his diocesan labors : a f atherly love for his beloved clergy, who had he1ned h so ch in the work a ccomn1ished a nd wi thout whom the Arohdiocese of w Orleans could never .ve de the spiritual progress set f orth in "the Report• I n t he words just auoted ere was likewi se expressed the program of a saoerdota1 and episoopal life whlch was about to olose ani which 11 ever r ema1n as a fonrl remembr ance in e hlstory of t his 100ese: ~' To evanp'eli the poor, to rejoice at being one of t hem, to e about the bua l neas of our He avenly r ather - al l this coupled with t he joy of bein ~ able to say t hat . -

In Defence of the Epistemological Objection to Divine Command Theory

In Defence of the Epistemological Objection to Divine Command Theory By John Danaher, NUI Galway Forthcoming in Sophia Abstract: Divine Command Theories (DCTs) comes in several different forms but at their core all of these theories claims that certain moral statuses (most typically the status of being obligatory) exist in virtue of the fact that God has commanded them to exist. Several authors argue that this core version of the DCT is vulnerable to an epistemological objection. According to this objection, DCT is deficient because certain groups of moral agents lack epistemic access to God’s commands. But there is confusion as to the precise nature and significance of this objection, and critiques of its key premises. In this article I try to clear up this confusion and address these critiques. I do so in three ways. First, I offer a simplified general version of the objection. Second, I address the leading criticisms of the premises of this objection, focusing in particular on the role of moral risk/uncertainty in our understanding of God’s commands. And third, I outline four possible interpretations of the argument, each with a differing degree of significance for the proponent of the DCT. 1. Introduction This article critiques Divine Command Theories (DCTs) of metaethics on the grounds that they involve an intimate connection between moral epistemology and moral ontology. More precisely, it argues that all DCTs incorporate an epistemic condition into their account of moral ontology and because of this they are vulnerable to an objection, viz. an important class of moral agents fail to satisfy this epistemic condition.