Homelessness-Binnen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(On the Applications of ZH and CN) (Appellants) V LB of Newham and LB of Lewisham

Michaelmas Term [2014] UKSC 62 On appeal from: [2013] EWCA Civ 804 and 805 JUDGMENT R (on the applications of ZH and CN) (Appellants) v London Borough of Newham and London Borough of Lewisham (Respondents) and Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government (Interested Party) before Lord Neuberger, President Lady Hale, Deputy President Lord Clarke Lord Wilson Lord Carnwath Lord Toulson Lord Hodge JUDGMENT GIVEN ON 12 November 2014 Heard on 23, 24 and 26 June 2014 Appellants Respondents Andrew Arden QC Matt Hutchings Toby Vanhegan Jennifer Oscroft Justin Bates Senay Nihat (Instructed by TV (Instructed by Head of Edwards LLP) Legal Services LB of Newham and LB of Lewisham) Intervener Martin Chamberlain QC Oliver Jones (Instructed by Treasury Solicitors) LORD HODGE (with whom Lord Wilson, Lord Clarke and Lord Toulson agree) 1. The issues in this appeal are (i) whether the Protection from Eviction Act 1977 (“PEA 1977”) requires a local housing authority to obtain a court order before taking possession of interim accommodation it provided to an apparently homeless person while it investigated whether it owed him or her a duty under Part VII of the Housing Act 1996 (“the 1996 Act”), and (ii) whether a public authority, which evicts such a person when its statutory duty to provide such interim accommodation ceases without first obtaining a court order for possession, violates that person’s rights under article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (“ECHR”). Factual background CN 2. CN was born on 3 August 1994. His mother (“JN”) applied to the London Borough of Lewisham (“Lewisham”) for assistance under Part VII of the 1996 Act in August 2009 and Lewisham arranged for a housing association to grant her an assured shorthold tenancy which commenced in May 2010. -

The Homelessness Legislation: an Independent Review of the Legal Duties Owed to Homeless People Contents

The homelessness legislation: an independent review of the legal duties owed to homeless people Contents Foreword from Lord Richard Best p.4 Foreword from the Panel Chair, Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick p.5 1. Introduction p.6 2. Homelessness legislation in England p.8 3. The impact of the current legislation on single homeless people p.11 4. Recent changes to homelessness legislation in the UK p.16 5. Our proposed alternative homelessness legislation p.20 6. The process map p.28 7. Conclusion p.30 8. Annex 1. Housing Act (1996) amended p.32 4 The homelessness legislation 5 Foreword from Lord Richard Best Foreword from the Panel Chair, Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick Over recent years Crisis has sustained its reputation for Homelessness legislation should serve as an important practical help and imaginative innovation in supporting safety net to help protect some of the most vulnerable people who are homeless. In particular, Crisis has people in our society. focussed the spotlight on single people who can fall outside the main homelessness duty of local authorities. However, within legislation in England there exists a All too often the acute shortages of housing in so many distinction between those who are considered ‘statutorily’ parts of the country - and particularly in London - are homeless and those who are not, predominately single felt most keenly by those with no legal entitlement to people without dependent children, who often receive accommodation and an uncertain claim to be “vulnerable”. very little help to prevent or end their homelessness. This creates a two-tier system and often leads to single homeless people suffering very poor outcomes. -

Cowan, D. (2019). Reducing Homelessness Or Re-Ordering the Deckchairs? Modern Law Review, 82(1), 105-128

Cowan, D. (2019). Reducing homelessness or re-ordering the deckchairs? Modern Law Review, 82(1), 105-128. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2230.12390 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1111/1468-2230.12390 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Wiley at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1468-2230.12390. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Reducing homelessness or re-ordering the deckchairs? Dave Cowan1 On the 40th anniversary of the enactment of the Housing (Homeless Persons) Act 1977, the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 passed in to law, and came in to effect on 2nd April 2018. Both were private members’ Bills, sponsored by Stephen Ross MP and Bob Blackman MP, but their passage through Parliament could not have been more different – the 1977 Act was heavily contested and amended during its passage; the 2017 Act was a cross-party affair, together with an interest group coalition, although, in tune with modern Parliamentary practice, there were 21 government amendments on third reading in the House of Commons. There have been -

The Law Commission RENTING HOMES 1: STATUS and SECURITY

The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 162 RENTING HOMES 1: STATUS AND SECURITY A Consultation Paper London: The Stationery Office The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Right Honourable Lord Justice Carnwath CVO, Chairman Professor Hugh Beale, QC Mr Stuart Bridge Professor Martin Partington Judge Alan Wilkie, QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WC1N 2BQ. This consultation paper, completed on 28 March 2002, is circulated for comment and criticism only. It does not represent the final views of the Law Commission. The Law Commission would be grateful for comments on this consultation paper before 12 July 2002. Comments may be sent – By post to: Helen Carr Law Commission Conquest House 37-38 John Street Theobalds Road London WC1N 2BQ Tel: 020-7453-1290 Fax: 020-7453-1297 By e-mail to: [email protected] It would be helpful if, where possible, comments sent by post could also be sent on disk, or by e-mail to the above address, in any commonly used format. All responses to this Consultation Paper will be treated as public documents, and may be made available to third parties, unless the respondent specifically requests that a response be treated as confidential, in whole or in part. The text of this consultation paper is available on the Internet at: http://www.lawcom.gov.uk 83-250-02 THE LAW COMMISSION -

Code of Guidance for Local Authorities

for Local Authorities on the Allocation of Accommodation and Homelessness March 2016 © Crown copyright 2016 WG28472 Digital ISBN: 978 1 4734 6395 0 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn Gymrae / This document is also available in Welsh. Code of Guidance Code CONTENTS Introduction About this Code of Guidance Purpose of the Code Target Audience Legal Status of the Code Structure of the Code Effective Dates of the Code Compliance with the Code The Legislation in Context Terminology Code up-dates Navigating the Code PART 1: ALLOCATIONS Chapter 1 Introduction Allocations and the Role of Social Landlords Improving Lives and Communities – Homes in Wales Housing White Paper, 2012 Communication Financial Inclusion Purpose of Part 1 of the Code Summary of Amendments to the Code Effective Date of Part 1 of Code Chapter 2 Eligibility for Housing Overview Definition of Allocation Eligible Categories Unacceptable Behaviour Policy Considerations Notification and Appeals to Decisions on Eligibility Residential Criteria Applications from Owner Occupiers No Fixed Address Chapter 3 The Allocations Scheme Balancing Priorities The Requirement to have an Allocation Scheme Transfer Applicants Civil Partnerships Joint Tenancies Succession Reasonable Preference Additional Preference Determining Priorities Choice and Preference Options Offers and Refusals Allocations Scheme Flexibility Meeting Diverse Needs Low Cost Home Ownership and Intermediate Rent Advice and Information Chapter 4 Allocation Scheme Management Housing Registers Allocations Scheme Consultation -

Housing and Social Policy

Housing and Social Policy This book looks at the changing nature of housing policy in the UK and how it relates to the economy and society generally. Contributors to the book consider the effects of market forces and state action on low-income households, different social classes, women, minority ethnic groups, and disabled people. It is argued that housing is a key focus for economic development, for social justice, for everyday lived experience, for class struggle, for gender and racial divisions, for organising the life course, and for physical and social regeneration. A key theme of the book is that, although housing is inextricably bound up with all aspects of our lives, we experience it in very different ways, depending on our social status, our spatial location, and our own physical, mental and financial characteristics. Contributors emphasise not only the differences among individuals, however, but also how the pattern of these differences can be understood through a focus on housing in particular. In this way, what appears to be a uniquely individualised experience can in reality be understood as a product of a complex web of interactions of different kinds, which assumes a relatively concrete shape in the context of housing. Categories of class, gender, race, disability and age are therefore shown to intersect while, at the same time, housing policy itself merges imperceptibly with other kinds of policy, such as economic, family, health, education, crime, and environment policy, under the ‘catch-all’ title of ‘regeneration’. Consequently, both housing experience and housing policy lose their specificity and become generalised as well as individualised. -

The Homelessness Legislation: an Independent Review of the Legal Duties Owed to Homeless People Contents

The homelessness legislation: an independent review of the legal duties owed to homeless people Contents Foreword from Lord Richard Best p.4 Foreword from the Panel Chair, Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick p.5 1. Introduction p.6 2. Homelessness legislation in England p.8 3. The impact of the current legislation on single homeless people p.11 4. Recent changes to homelessness legislation in the UK p.16 5. Our proposed alternative homelessness legislation p.20 6. The process map p.28 7. Conclusion p.30 8. Annex 1. Housing Act (1996) amended p.32 4 The homelessness legislation 5 Foreword from Lord Richard Best Foreword from the Panel Chair, Professor Suzanne Fitzpatrick Over recent years Crisis has sustained its reputation for Homelessness legislation should serve as an important practical help and imaginative innovation in supporting safety net to help protect some of the most vulnerable people who are homeless. In particular, Crisis has people in our society. focussed the spotlight on single people who can fall outside the main homelessness duty of local authorities. However, within legislation in England there exists a All too often the acute shortages of housing in so many distinction between those who are considered ‘statutorily’ parts of the country - and particularly in London - are homeless and those who are not, predominately single felt most keenly by those with no legal entitlement to people without dependent children, who often receive accommodation and an uncertain claim to be “vulnerable”. very little help to prevent or end their homelessness. This creates a two-tier system and often leads to single homeless people suffering very poor outcomes. -

Homelessness Code of Guidance for Local Authorities

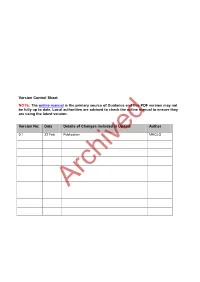

Version Control Sheet NOTE: The online manual is the primary source of Guidance and this PDF version may not be fully up to date. Local authorities are advised to check the online manual to ensure they are using the latest version. Version No: Date Details of Changes included in Update Author 0.1 22 Feb Publication MHCLG Archived Homelessness Code of Guidance for Local Authorities Archived February 2018 Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government © Crown copyright, 2018 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence,http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. This document/publication is also available on our website at www.gov.uk/mhclg If you have any enquiries regarding this document/publication, complete the form at http://forms.communities.gov.uk/ or write to us at: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government Fry Building 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Telephone: 030 3444 0000 For all our latest news and updates follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/mhclg February 2018 ISBN: 978-1-4098-5201-8 Contents Definitions 5 Overview of the homelessness legislation 6 Chapter 1: Introduction 11 Chapter 2: Homelessness strategies and reviews 17 Chapter 3: Advice and information -

Statutory Homelessness in England

BRIEFING PAPER Number 01164, 26 November 2020 Statutory Homelessness By Wendy Wilson in England Cassie Barton Inside: 1. Local authorities’ duties: an overview 2. The causes of homelessness 3. Statistics on statutory homelessness 4. How are local authorities performing? 5. Government policy & comment www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 01164, 26 November 2020 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Local authorities’ duties: an overview 6 1.1 Duties owed to homeless applicants 6 1.2 Homelessness strategies 9 2. The causes of homelessness 10 The end of an assured shorthold tenancy (AST) 12 Housing Benefit restrictions and Universal Credit 14 Government research into the causes of homelessness 17 3. Statistics on statutory homelessness 19 3.1 Where do homelessness statistics come from? 19 3.2 Official statistics 20 Prevention and relief duties: April to June 2020 20 Background of households applying for help 22 How are homelessness duties ended? 27 Households in temporary accommodation: June 2020 29 3.3 Other estimates of homelessness 29 4. How are local authorities performing? 31 4.1 Meeting their homelessness duties 31 The impact of the Homelessness Reduction Act (HRA) 2017 32 Outcome of the Government response to the call for evidence (September 2020) 36 4.2 Use of private rented & out of borough placements 37 4.3 Homeless young people 39 4.4 Access to housing association tenancies 41 5. Government policy & comment 42 5.1 Increasing housing supply 42 5.2 A commitment to reduce homelessness 44 5.3 Insecure private rented sector tenancies 44 5.4 Welfare reform 45 5.5 Funding to tackle homelessness 47 Value for money? 51 5.6 Are other measures needed? 53 5.7 The impact of Covid-19 55 Contributing authors Cassie Barton, statistics Cover page image copyright: Hamed’s house by BBC World Service. -

An International Review of Homelessness and Social Housing Policy

An International Review of Homelessness and Social Housing Policy www.communities.gov.uk community, opportunity, prosperity An International Review of Homelessness and Social Housing Policy Suzanne Fitzpatrick and Mark Stephens Centre for Housing Policy, University of York November 2007 Department for Communities and Local Government: London The findings and recommendations in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the view of the Department for Communities and Local Government Department for Communities and Local Government Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone: 020 7944 4400 Website: www.communities.gov.uk © Queen’s Printer and Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2007 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication, excluding logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. Any other use of the contents of this publication would require a copyright licence. Please apply for a Click-Use Licence for core material at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/system/online/pLogin.asp, or by writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or email: [email protected] If -

Homelessness Code of Guidance for Local Authorities

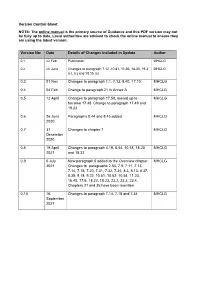

Version Control Sheet NOTE: The online manual is the primary source of Guidance and this PDF version may not be fully up to date. Local authorities are advised to check the online manual to ensure they are using the latest version. Version No: Date Details of Changes included in Update Author 0.1 22 Feb Publication MHCLG 0.2 20 June Changes to paragraph 7.12 ,10.41, 11.36, 14.30, 19.3 MHCLG (c), (e) and 19.15 (a) 0.3 01 Nov Changes to paragraph 1.1, 7.12, 8.40, 17.10 MHCLG 0.4 04 Feb Change to paragraph 21 in Annex A MHCLG 0.5 12 April Changes to paragraph 17.58, moved up to MHCLG become 17.48. Change to paragraph 17.49 and 19.23 0.6 26 June Paragraphs 8.44 and 8.45 added MHCLG 2020 0.7 31 Changes to chapter 7 MHCLG December 2020 0.8 19 April Changes to paragraph 4.19, 8.44, 10.18, 18.30 MHCLG 2021 and 18.32 0.9 5 July New paragraph 5 added to the Overview chapter. MHCLG 2021 Changes to paragraphs 2.53, 7.9, 7.11, 7.13, 7.14, 7.18, 7.20, 7.31, 7.32, 7.34, 8.3, 8.13, 8.37, 8.38, 9.18, 9.22, 10.51, 10.52, 10.54, 11.23, 16.40, 17.6, 18.22, 18.23, 23.2, 23.3, 23.4. Chapters 21 and 25 have been rewritten. 0.10 16 Changes to paragraph 7.14, 7.18 and 7.34 MHCLG September 2021 Homelessness Code of Guidance for Local Authorities February 2018 Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government © Crown copyright, 2018 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Crime control through housing management Cobb, Neil Anthony How to cite: Cobb, Neil Anthony (2005) Crime control through housing management, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3004/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk CRIME CONTROL THROUGH HOUSING MANAGEMENT NEIL ANTHONY COBB DEPARTMENT OF LAW THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF JURISPRUDENCE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM 2005 A copyright of this thesis rests with the au,thor. No qlllotation from it should lbe published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ABSTRACT Crime control through housing management Neil Anthony Cobb M.Jur Thesis 2005 Over the last decade the management of social housing in England and Wales has extended to the formal control of bad behaviour. This thesis charts the political development of this increasingly important function and the legal infrastructure within which it operates.