The Tempest (Review) Virginia Mason Vaughan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Theory for Subjectivity in the Psychological Humanities Complicities

PALGRAVE STUDIES IN THE THEORY AND HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY Complicities A theory for subjectivity in the psychological humanities Natasha Distiller Palgrave Studies in the Theory and History of Psychology Series Editor Thomas Teo Department of Psychology York University Toronto, ON, Canada Palgrave Studies in the Teory and History of Psychology publishes schol- arly books that use historical and theoretical methods to critically examine the historical development and contemporary status of psychological con- cepts, methods, research, theories, and interventions. Books in this series are characterised by one, or a combination of, the following: (a) an empha- sis on the concrete particulars of psychologists' scientifc and professional practices, together with a critical examination of the assumptions that attend their use; (b) expanding the horizon of the discipline to include more interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary work performed by researchers and practitioners inside and outside of the discipline, increasing the knowl- edge created by the psychological humanities; (c) “doing justice” to the persons, communities, marginalized and oppressed people, or to academic ideas such as science or objectivity, or to critical concepts such social justice, resistance, agency, power, and democratic research. Tese examinations are anchored in clear, accessible descriptions of what psychologists do and believe about their activities. All the books in the series share the aim of advancing the scientifc and professional practices of psychology and psy- chologists, even as they ofer probing and detailed questioning and critical reconstructions of these practices. Te series welcomes proposals for edited and authored works, in the form of full-length monographs or Palgrave Pivots; contact [email protected] for further information. -

Wakanda Forever

3 Wakanda Forever Racism is a system whose function is to confer privilege. Tat privilege has two main components, economic and psychic. Racism as a system is fundamentally reliant on binary thinking in order to build the symbolic meanings on which its material practices are erected. Historically and philosophically, racism is an implicit part of the well-intentioned liberal- ism which has crafted the individualized subject of Western psychology. As Perry (2018) has shown, the processes of the Enlightenment, together with the genocide and slavery that accompanied the colonialism which made modernity, needed a category of nonpersons in order to authorize and enrich the gendered and classed person who was a product of these historical forces. Tese processes of person production were as much eco- nomic and legal as they were psychological, showing once more the imbrication of all these forces. Racism, of course, makes use of the construct of race to authorize itself. Tere is no scientifc validity to the construct of race. Tere is only one, human race, although there are geographically regional genetic vari- ants of humans. All the scientifc and psychological work on race and putative racial diferences in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was research done on “something which was not there” (Richards, 2012, p. 19; © Te Author(s) 2022 73 N. Distiller, Complicities, Palgrave Studies in the Teory and History of Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79675-4_3 74 N. Distiller see Posel, 2001; Richeson & Sommers, 2016). Or, as Oluo (2019, pp. 11–12) puts it, race is “a lie told to justify a crime” (see also Kendi, 2016). -

Carnegie Hall Announces 2014–2015 Season Ubuntu

Date: January 29, 2014 Contact: Synneve Carlino Tel: 212-903-9750 E-mail: [email protected] CARNEGIE HALL ANNOUNCES 2014–2015 SEASON UBUNTU: Music and Arts of South Africa Three-Week Citywide Festival Explores South Africa’s Dynamic and Diverse Culture With Dozens of Concerts and Events Including Music, Film, Visual Art, and More Perspectives: Joyce DiDonato and Anne-Sophie Mutter Renowned Mezzo-Soprano Joyce DiDonato Curates Multi-Event Series with Music Ranging from Baroque to Bel Canto to Premieres of New Works, Plus Participation in a Range of Carnegie Hall Music Education Initiatives Acclaimed Violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter Creates Six-Concert Series, Appearing as Orchestra Soloist, Chamber Musician, and Recitalist, Including Collaborations with Young Artists Debs Composer’s Chair: Meredith Monk Works by Visionary Composer Featured in Six-Concert Residency, Including Celebration of Monk’s 50th Anniversary of Creating Work in New York City Before Bach Month-Long Series in April 2015 Features 13 Concerts Showcasing Many of the World’s Most Exciting Early-Music Performers October 2014 Concerts by the Berliner Philharmoniker and Sir Simon Rattle, Including Opening Night Gala Performance with Anne-Sophie Mutter, Herald Start of New Season Featuring World’s Finest Artists and Ensembles Andris Nelsons Leads Inaugural New York City Concerts as Music Director of Boston Symphony Orchestra in April 2015 All-Star Duos Highlight Rich Line-Up of Chamber Music Concerts and Recitals, Including Performances by Leonidas Kavakos & Yuja Wang; Gidon -

Theatre Reviews

Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance Volume 8 Article 10 November 2011 Theatre Reviews Coen Heijes University of Groningen, the Netherlands Xenia Georgopoulou Department of Theatre Studies of the University of Athens, Greece Nektarios-Georgios Konstantinidis French Department of the University of Athens, Greece Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/multishake Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Heijes, Coen; Georgopoulou, Xenia; and Konstantinidis, Nektarios-Georgios (2011) "Theatre Reviews," Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance: Vol. 8 , Article 10. DOI: 10.2478/v10224-011-0010-9 Available at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/multishake/vol8/iss23/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance , vol. 8 (23), 2011 DOI: 10.2478/v10224-011-0010-9 Theatre Reviews The Tempest . Dir. Janice Honeyman. The Baxter Theatre Centre (Cape Town, South Africa) and the Royal Shakespeare Company (Stratford-upon- Avon, United Kingdom). a Reviewed by Coen Heijes The Multiple Faces of a Multicultural Society The last twenty lines of The Tempest are spoken by Prospero. They are an epilogue in which he asks the audience both for applause and for forgiveness in order to set him, the actor, free. The stage directions indicate that Prospero is by now alone on stage, all the other characters having left in the course of scene 5.1. -

LESSONS from WAKANDA: Pan-Africanism As the Antidote to Robotisation,THE BLACK PANTHER PHENOMENON: Bridging the Rift Between

LESSONS FROM WAKANDA: Pan-Africanism as the antidote to robotisation By Horace G. Campbell In May 2013, the African Union launched Agenda 2063, a blueprint for an integrated, emancipated, prosperous and peaceful Africa. There was a renewed commitment to work for the full unification of Africa, with a common currency from one common bank of issue, a continental communication system, a common foreign policy and a common defence system featuring the African high command. Five years later, Hollywood came out with a fictional story of a bountiful, independent African state called Wakanda in the film Black Panther. Wakanda was described as the most scientifically and technologically advanced civilisation in the world — not to mention the wealthiest. It is not a coincidence that there is a straight line between the aspirations of the Global African Family, as expressed in Agenda 2063, and the depiction of a technologically advanced Africa. From the era of the writings of C. L. R James on the majesty of the Haitian Revolution to the current struggle for the dignity of black lives, the liberation and unification of Africa has always been presented as the basis for Pan-Africanism. Examining the meaning of Pan-Africanism in the current context of massive technological change requires a new language and a new orientation – an orientation that breaks away from the stultifying concepts embraced by a class of leaders who have no loyalty to Africa and who seek to turn citizens into tribal nanobots without a spiritual core. We are reminded that in this era of artificial intelligence (AI) the future of humanity is the struggle between humans that control machines and machines that control humans. -

Black Popular Culture

BLACK POPULAR CULTURE THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL AFRICOLOGY: A:JPAS THE JOURNAL OF PAN AFRICAN STUDIES Volume 8 | Number 2 | September 2020 Special Issue Editor: Dr. Angela Spence Nelson Cover Art: “Wakanda Forever” Dr. Michelle Ferrier POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State Bowling Green State University University University JUDITH FATHALLAH KATIE FREDRICKS KIT MEDJESKY Solent University Rutgers University University of Findlay JESSE KAVADLO ANGELA M. -

From South Africa's Acclaimed Market Theatre, Sizwe Banzi Is Dead Starts February 25 at Syracuse Stage

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Friday, February 20, 2015 CONTACT: Patrick Finlon, Marketing Director 315-443-2636 or [email protected] From South Africa’s Acclaimed Market Theatre, Sizwe Banzi is Dead Starts February 25 at Syracuse Stage “A joyous hymn to human nature.”—THE NEW YORK TIMES “Hypnotic… Powerful.”—BLOOMBERG Co-Produced with The Market Theatre (Johannesburg, South Africa) & McCarter Theatre Center (Princeton, NJ) PRESENTING SPONSOR: SPONSOR: MEDIA SPONSORS: SEASON SPONSOR: Robert Sterling Clark Chase Bank Urban CNY Syracuse Media Group Foundation WRVO Public Media (Syracuse, NY)—From South Africa’s acclaimed Market Theatre, the intensely funny and poignant Sizwe Banzi is Dead starts February 25 at Syracuse Stage. In this award-winning classic about the universal struggle for human dignity, a black man in apartheid-era South Africa tries to overcome oppressive work regulations to support his family. Co-creator John Kani performed in the original production and won the 1975 Tony Award for Best Actor. Now, 40 years later, Kani directs his son, Atandwa Kani, in this new international production. Sizwe Banzi is Dead performs Feb. 25 – March 15 in the Archbold Theatre at the Syracuse Stage/Drama Complex, 820 East Genesee Street. Discounted preview performances are Feb. 25 and 26. The Opening Night performance is Friday, Feb. 27 at 8 p.m. Tickets and info are available at www.syracusestage.org, by phone at 315-443-3275, and in person at the Syracuse Stage Box Office, Mon-Fri, 10am-5pm. Ticket discounts are available for groups of 10 or more at 315-443-9844. Discounts are also available for seniors, students, and U.S. -

Thetha July 2019

ThethaAlumni & Friends Magazine, July 2019 BIG BLUE Saving our oceans #FAST FORWARD The future is here LIONHEART Madibaz’ bowler Lutho Sipamla is pitch perfect Hey, John Man! Meeting Mr Kani Ghosts in a forest The last Knysna elephant 12 23 32 CONTENTS Our Ability to Imagine and Reimagine 4 Publisher: Paul Geswindt 42 Editor: 53 Centenary Celebrations 7 Debbie Derry Lead writer: Heather Dugmore Building a more inclusive future 9 Writers: Nicky Willemse, Cathy Dippenall, Lize Hayward, Fast Forward 12 Full Stop Communications, Debbie Derry, Zandile Mbabela Production: Lyndall Sa Joe-Derrocks African wave 13 Designer: Juliana Jangara Port Elizabeth an emerging software hub 16 Photography: Leonette Bower Green wheels 19 Sub-editors: Beth Cooper Howell and Jill Wolvaardt One ocean, many lives 23 Cover Image: Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) with a plastic Sun sense 29 bag. The bag was removed by the photographer before the Hey, John Man 32 turtle had a chance to eat it. Credit: © Troy Mayne / WWF WWF is advocating for national governments to support a 38 My secret to success legally binding agreement on marine plastic pollution. Clean corporate governance 40 And then there was one 42 Mandela University thanks the following photographers, individuals and organisations for their illustrations: ‘Extinct’ fynbos species rediscovered 47 Chris Adendorff, Parmi Natesan, Quinton Uren, S4 Integration, Fanning the flames 49 Nelson Mandela Bay iHub, Jean Greyling, Nelson Mandela Bay Leader of the pack 53 Tourism, The Market Theatre, The PE Opera House, -

Theatre Experience

i The Theatre Experience 1 iii The Theatre Experience F O U R T E E N T H E D I T I O N EDWIN WILSON Professor Emeritus Graduate School and University Center The City University of New York 2 iv THE THEATRE EXPERIENCE, FOURTEENTH EDITION Published by McGraw-Hill Education, 2 Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10121. Copyright © 2020 by Edwin Wilson. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Previous editions © 2015, 2011, and 2009. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education, including, but not limited to, in any network or other electronic storage or transmission, or broadcast for distance learning. Some ancillaries, including electronic and print components, may not be available to customers outside the United States. This book is printed on acid-free paper. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 LWI 21 20 19 18 ISBN 978-1-260-05607-5 (bound edition) MHID 1-260-05607-4 (bound edition) ISBN 978-1-260-49340-5 (loose-leaf edition) MHID 1-260-49340-7 (loose-leaf edition) Portfolio Manager: Sarah Remington Lead Product Developer: Mary Ellen Curley Senior Product Developer: Beth Tripmacher Senior Content Project Manager: Danielle Clement Content Project Manager: Emily Windelborn Senior Buyer: Laura Fuller Design: Egzon Shaqiri Content Licensing Specialist: Ann Marie Jannette Cover Image: ©Sara Krulwich/The New York Times/Redux Compositor: MPS Limited All credits appearing on page or at the end of the book are considered to be an extension of the copyright page. -

Donovan Marsh • David Jammy • Atandwa Kani • Janine Eser

DONOVAN MARSH • DAVID JAMMY • ATANDWA KANI • JANINE ESER The magaine for ALUMNI and friends of the University of the Witwatersrand April 2020, Volume 43 CO-STARRING: NICK BORAINE (ACTOR) • GARY BARBER (FORMER CHAIR & CEO MGM, CURRENT CEO OF SPYGLASS MEDIA GROUP) • JOHNATHAN DORFMAN (PRODUCER, FOUNDER, ATO PICTURES) • GAVIN HOOD (DIRECTOR, PRODUCER, ACTOR, SCREENWRITER) • LOUISE BARNES-BORAINE (ACTOR) • PB APRIL 2020 / NADINE ZYLSTRA (DIRECTOR) • GIDEON EMERY (ACTOR) • JASON KENNETT (ACTOR) • ALAN LAZAR (COMPOSER,Wits Review, DIRECTOR) 1 Vice-Chancellor's Note Tumultuous times if we act decisively, we will overcome it.” As Wits, we are doing just that and ensuring the safety of our students and staff during this critical time. Orde Eliason I also need to announce with great sadness that I Image: will be leaving Wits at the end of 2020. By the end of the year, I will have served most of my second, and final, term of office as Vice-Chancellor at Wits. I have decided to take up the position as Director of Build lives. the School of Oriental and African Studies in London with effect from January 2021. Change futures It has been an honour and privilege to serve as Vice-Chancellor of Wits University for eight years. We have lived through some tumultuous times during my term of office and we would not have survived these times without the collective voice of all constituencies – including that of our alumni WITS – being heard at crucial moments. Throughout my tenure, various Wits constituencies have provided wise counsel and support without which we would ANNUAL FUND not have been able to survive institutionally and I thank you for that. -

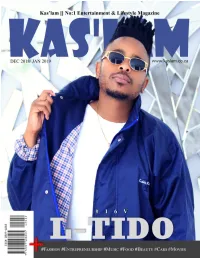

Ltidokaslam.Pdf

Click Or Tap to Skip to page Cover: L-Tido 16V: A true living legend of the game and after 10 he is unveiling a new chapter to further advance his ca- 19 reer. (Page 19) Nyovest (08;09) Listening session 09 08 I’m I’m grate- ful of the 10 coming for oppor- Everything in tunity given to me this industry. by the lord al- mighty– Sihle - Bongani Drama 13 FASHION Check out the 10 Men’s Health Fash- ion Show review brought to you by 26 RuffCart To improve South Africa, I would MOVIE OF THE Stimulate the economy, Advocate MONTH for a policy that’s focused on growing the economy, Job oppor- tunities and a strict act against crime and corruption. …(10) 29 THERE’S NOTHING LIKE A COUPLE’S GAME NIGHT FOR AN EASY AT HOME DATE IDEA(23) 36 Surprise dream location 34 BENEFITS OF CRANBERRY JUICE www.kaslam.co.za The Team That brings you this Digital Manager: TRapz great Magazine every month Tumelo Rapodile [email protected] Managing Editor & Director: Bobo.M thefuture Facebook: Tumelo Trapz Rapodile Bonginkosi Mhlanga Instagram: TRapz_SA [email protected] Facebook: Bobo M thefuture Fashion Editor 1: Mike (RuffCart) Instagram: Bobomthefuture Instagram: Ruffcart Family Facebook: Ruffcart Family holding PR Manager Koketso Ramego [email protected] Advertising : Salim Moripe Facebook: Koketso Ramego Facebook: Salim Moripe Email : [email protected] Events Photography 2 : TWITTER: @3rdWorldSalim Rune Sibiya [email protected] Facebook: Thulani Rune Sibiya PLEASE CLICK ON ALL ADVERTS TO VIEW Main Photography : Naledi Mayekiso MORE DETAILS ABOUT THE PRODUCT !!! [email protected] Facebook: Naledi Mayekiso Instagram: NalediMayekiso Make UP Artist & Profile features Precious McJane Facebook: Precious McJane Instagram: Precious_McJane All the celeb interviews on Kas’lam TV [email protected] Click watch now !!! Graphic Designer: Egma Mhlanga [email protected] Facebook: kas’lam magazine Thank you for downloading our issue. -

Our Dreams Are Valid

Our Dreams Are Valid By Oyunga Pala On March 1, 2018, two weeks after its release, Black Panther movie was approaching a billion dollars in ticket sales. 10 days in, the movie leapt past the $400 million mark in domestic box office in the USA and over $700 million across the world. That is Stars Wars territory but with an All Black Cast to boot in a Marvel feature. This is the movie equivalent to the US Dream Team, at the 1992 Olympics at Barcelona. Never before had a finer group of talented basketballers come together and when they did, they took the world by storm. Black Panther is having its dream team moment as the showcase for black excellence and representation in cinema. Black Panther is a beautifully shot film. The fictional country Wakanda is rich in detail. The central story is about belonging and heritage. Ryan Coolger, the 31-year-old African American director looks at Africa with a different set of eyes and response to this film in Kenya has been tremendous. A film is big when people pack theatres weekend after weekend and even during the weekdays to experience the magic of the big screen despite our home entertainment movie culture. Black Panther is a tale told by Africans about a place far away that they call home. In some respects, an African dream inspired by Marcus Garvey’s rallying call to the African diaspora, “ Look to Africa, where a black king shall be crowned for the day of deliverance is at hand”. Ryan Coolger said in a Rolling Stone interview that Black Panther explored what it meant to be African.