Donation After Circulatory Death: Current Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transplant Immunology.Pdf

POLICY BRIEFING Transplant Immunology September 2017 The British Society of Immunology is the largest Introduction immunology society in Europe. Our mission is to promote excellence in immunological research, scholarship and Transplantation is the process of moving cells, tissues, or clinical practice in order to improve human and animal organs, from one site to another, either within the same health. We represent the interests of more than 3,000 person or between a donor and a recipient. If an organ immunologists working in academia, clinical medicine, system fails, or becomes damaged as a consequence of and industry. We have strong international links and disease or injury, it can be replaced with a healthy organ collaborate with our European, American and Asian or tissue from a donor. partner societies in order to achieve our aims. Organ transplantation is a major operation and is only Key points: offered when all other treatment options have failed. Consequently, it is often a life-saving intervention. In • Transplantation is the process of moving cells, 2015/16, 4,601 patient lives were saved or improved in i tissues or organs from one site to another for the the UK by an organ transplant. Kidney transplants are purpose of replacing or repairing damaged or the most common organ transplanted on the NHS in diseased organs and tissues. It saves thousands the UK (3,265 in 2015/16), followed by the liver (925), and i of lives each year. However, the immune system pancreas (230). In addition, a total of 383 combined heart poses a significant barrier to successful organ and lung transplants were performed, while in 2015/16. -

Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series

Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series National Council on Disability September 25, 2019 National Council on Disability (NCD) 1331 F Street NW, Suite 850 Washington, DC 20004 Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities: Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series National Council on Disability, September 25, 2019 This report is also available in alternative formats. Please visit the National Council on Disability (NCD) website (www.ncd.gov) or contact NCD to request an alternative format using the following information: [email protected] Email 202-272-2004 Voice 202-272-2022 Fax The views contained in this report do not necessarily represent those of the Administration, as this and all NCD documents are not subject to the A-19 Executive Branch review process. National Council on Disability An independent federal agency making recommendations to the President and Congress to enhance the quality of life for all Americans with disabilities and their families. Letter of Transmittal September 25, 2019 The President The White House Washington, DC 20500 Dear Mr. President, On behalf of the National Council on Disability (NCD), I am pleased to submit Organ Transplants and Discrimination Against People with Disabilities, part of a five-report series on the intersection of disability and bioethics. This report, and the others in the series, focuses on how the historical and continued devaluation of the lives of people with disabilities by the medical community, legislators, researchers, and even health economists, perpetuates unequal access to medical care, including life- saving care. Organ transplants save lives. But for far too long, people with disabilities have been denied organ transplants as a result of unfounded assumptions about their quality of life and misconceptions about their ability to comply with post-operative care. -

Organ Donation Opportunites for Action

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11643.html We ship printed books within 1 business day; personal PDFs are available immediately. Organ Donation: Opportunities for Action Committee on Increasing Rates of Organ Donation, James F. Childress and Catharyn T. Liverman, Editors ISBN: 0-309-65733-4, 358 pages, 6 x 9, (2006) This PDF is available from the National Academies Press at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11643.html Visit the National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council: • Download hundreds of free books in PDF • Read thousands of books online for free • Explore our innovative research tools – try the “Research Dashboard” now! • Sign up to be notified when new books are published • Purchase printed books and selected PDF files Thank you for downloading this PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may contact our customer service department toll- free at 888-624-8373, visit us online, or send an email to [email protected]. This book plus thousands more are available at http://www.nap.edu. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF File are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Distribution, posting, or copying is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Request reprint permission for this book. Organ Donation: Opportunities for Action http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11643.html ORGAN DONATION OPPORTUNITIES FOR ACTION Committee on Increasing Rates of Organ Donation Board on Health Sciences Policy James F. -

Organ and Tissue Donation

ORGAN AND TISSUE DONATION www.kidney.org If I needed a kidney or some other vital organ to live… would I be able to get one? Maybe. Some people who need organ transplants cannot get them because of a shortage of donations. The national waiting list for organ transplants grows longer every day. Thousands die each year while waiting for a transplant of a vital organ, such as a kidney, heart, or liver. How are organs and tissues for transplantation obtained? Organs can be donated by people at the time of death (deceased donors) or by living donors. A living donor may be a relative, friend, or possibly someone who does not know the recipient but wishes to be a donor for someone in need. This brochure provides information about organ and tissue donation at the time of death. For more information about living donation, visit www.kidney.org/livingdonors How are donated organs and tissues distributed? The federal government contracts with an independent organization, called 2 NATIONAL KIDNEY FOUNDATION the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), to manage the distribution of organs donated by individuals at the time of death (deceased donors). Because of the shortage of donations, transplant candidates’ names are placed on a waiting list. Guidelines have been established to ensure that all patients on the waiting list have a fair chance at receiving the organ they need regardless of age, sex, race, lifestyle, or social status. Organs are also distributed based on needs and medical criteria. Donated tissues are distributed through a separate process, which is coordinated by various tissue banks. -

1 SAMPLE PERSUASIVE SPEECH Title: Organ Donation Specific

SAMPLE PERSUASIVE SPEECH Title: Organ Donation Specific Purpose: To persuade my audience to donate their organs and tissues when they die and to act upon their decision to donate. Thesis Statement: The need is constantly growing for organ donors and it is very simple to become an organ donor. INTRODUCTION I) How do you feel when you have to wait for something you really, really want? What if it was something you literally couldn’t live without? II) The need is constantly growing for organ donors and it is very simple to become an organ donor. III) Today I’d like to talk to you about the need for organ donors in our area, how organ donor recipients benefit from your donation, and how you can become an organ donor today. IV) I am credible to speak about this topic because I did a lot of research on organ donation and because I am an organ donor myself. (I’ll begin by telling you about the need for organ donors.) BODY I) People around the world and also right here in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Illinois, need organ transplants and they need our help. A) The problem is that there is a lack of organs and organ donors who make organ transplantation possible (Smith 35). B) According to Jane Green and Jim Lee, authors of “Organ Donations in Minnesota,” the number of organ donors in our area has diminished to a low 23% (Green and Lee 23). (Now that you see the great need for organ donors in our area, let’s look at what may happen if you choose to donate your organs.) II) Organ donation benefits both the donor’s family and the recipients. -

Management of Donation After Brain Death (DBD) in The

Intensive Care Med (2019) 45:322–330 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05574-5 REVIEW Management of donation after brain death (DBD) in the ICU: the potential donor is identifed, what’s next? Ignacio Martin‑Loeches1* , Alberto Sandiumenge2, Julien Charpentier3, John A. Kellum4, Alan M. Gafney5, Francesco Procaccio6 and Glauco A. Westphal7 © 2019 Springer‑Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature Abstract The success of any donation process requires that potential brain‑dead donors (PBDD) are detected and referred early to professionals responsible for their evaluation and conversion to actual donors. The intensivist plays a crucial role in organ donation. However, identifcation and referral of PBDDs may be suboptimal in the critical care environ‑ ment. Factors infuencing lower rates of detection and referral include the lack of specifc training and the need to provide concomitant urgent care to other critically ill patients. Excellent communication between the ICU staf and the procurement organization is necessary to ensure the optimization of both the number and quality of organs transplanted. The organ donation process has been improved over the last two decades with the involvement and commitment of many healthcare professionals. Clinical protocols have been developed and implemented to better organize the multidisciplinary approach to organ donation. In this manuscript, we aim to highlight the main steps of organ donation, taking into account the following: early identifcation and evaluation of the PBDD with the use of checklists; -

A Thesis Entitled Factors That Explain and Predict Organ Donation

A Thesis entitled Factors that Explain and Predict Organ Donation Registration: An Application of the Integrated Behavioral Model by Matthew Robert Jordan Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Science Degree in Health Outcomes and Socioeconomic Sciences ________________________________________ Dr. Sharrel L. Pinto, Committee Chair ________________________________________ Dr. Timothy R. Jordan, Committee Member ________________________________________ Dr. Cindy S. Puffer, Committee Member ________________________________________ Dr. Amanda Bryant-Friedrich, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo August 2017 Copyright 2017, Matthew Robert Jordan This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Factors that Explain and Predict Organ Donation Registration: An Application of the Integrated Behavioral Model by Matthew Robert Jordan Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Science Degree in Health Outcomes and Socioeconomic Sciences The University of Toledo August 2017 Background: Organ transplantation became a new hope for those living with end-stage organ disease. However, the number of patients waiting for this procedure greatly exceeds the number of available donors. This separation leads to the death of almost 30 Americans per day who are waiting for this life changing procedure. Although Americans have shown a high level of support for organ donation, a large gap exists between the support and intention to register. As one of the most trusted and accessible healthcare professionals, pharmacist may have an opportunity to provide expanded services and education to the public and patients about organ donation. -

Organ Donation and Recovery Improvement Act

PUBLIC LAW 108–216—APR. 5, 2004 ORGAN DONATION AND RECOVERY IMPROVEMENT ACT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 22:34 Apr 07, 2004 Jkt 029139 PO 00216 Frm 00001 Fmt 6579 Sfmt 6579 E:\PUBLAW\PUBL216.108 SUEP PsN: PUBL216 118 STAT. 584 PUBLIC LAW 108–216—APR. 5, 2004 Public Law 108–216 108th Congress An Act Apr. 5, 2004 To amend the Public Health Service Act to promote organ donation, and for other [H.R. 3926} purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Organ Donation the United States of America in Congress assembled, and Recovery Improvement SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. Act. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Organ Donation and Recovery 42 USC 201 note. Improvement Act’’. SEC. 2. SENSE OF CONGRESS. (a) PUBLIC AWARENESS OF NEED FOR ORGAN DONATION.—It is the sense of Congress that the Federal Government should carry out programs to educate the public with respect to organ donation, including the need to provide for an adequate rate of such donations. (b) FAMILY DISCUSSIONS OF ORGAN DONATIONS.—Congress rec- ognizes the importance of families pledging to each other to share their lives as organ and tissue donors and acknowledges the impor- tance of discussing organ and tissue donation as a family. (c) LIVING DONATIONS OF ORGANS.—Congress— (1) recognizes the generous contribution made by each living individual who has donated an organ to save a life; and (2) acknowledges the advances in medical technology that have enabled organ transplantation with organs donated by living individuals to become a viable treatment option for an increasing number of patients. -

THE MEDICAL DIRECTIVE As Part of a Person’S Right to Self-Determination, Every Adult May Accept Or Refuse Any Recommended Medical Treatment

THE MEDICAL DIRECTIVE As part of a person’s right to self-determination, every adult may accept or refuse any recommended medical treatment. This is relatively easy when people are well and can speak. Unfortunately, during severe illness people are often unconscious or otherwise unable to communicate their wishes at the very time when many critical decisions need to be made. Iowa law insures that the rights and desires of the seriously ill are honored. It provides that adults can direct, in advance, whether they want to be kept alive by artificial means in the event they become seriously ill and incapable of taking part in decisions regarding their medical care. This written Medical Directive is sometimes called a “living will.” WHAT THE MEDICAL DIRECTIVE DOES The Medical Directive states your wishes regarding various types of medical treatment in several representative situations so that your desires can be respected. The Medical Directive also lets you appoint someone to make medical decisions for you if you should become unable to make your own; this is an “attorney-in-fact,” a “proxy,” or “durable power of attorney.” Additionally, it contains a statement of your wishes concerning organ donation. HOW TO MAKE YOUR MEDICAL DIRECTIVE The following pages contain a Medical Directive form on which you can record your own desires. You may want to discuss the issues with your family, friends or religious mentor, as well as your personal physician and attorney, before completing the form. Please refer to pages 7-9 for details on the signing and witnessing of the Medical Directive. -

Ethics of Organ Transplantation

Ethics of Organ Transplantation Center for Bioethics February 2004 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDICAL ISSUES What is organ transplantation? ……………………………………...Page 5 The transplant process ………….………………………...…………. Page 6 Distributing cadaveric organs ………………………………………..Page 7 A history of organ transplantation …………………….…………….Page 9 Timeline of medical and legal advances in organ transplantation…Page 10 ETHICAL ISSUES Ethical Issues Part I: The Organ Shortage……..………...………… Page 13 Distribution of available organs …….………………………. Page 15 Current distribution policy …………………………………..Page 17 Organ shortage ethical questions …………………………… Page 19 Ethical Issues Part II: Donor Organs ......…………………………... Page 20 Cadaveric organ donation ……………………………………Page 20 Living organ donation ……………………………………….. Page 24 Alternative organs …………………………………………… Page 27 LEGAL AND SOCIAL ISSUES Current laws …………………………………………………………. Page 29 The impact of transplantation ………………………………………. Page 31 OTHER MATERIALS Books and articles …………………………………………………….Page 33 Glossary ………………………………………………………………. Page 39 References ……………………………………………………………. Page 41 3 4 MEDICAL ISSUES What is organ transplantation? An organ transplant is a surgical operation WHAT ARE ORGANS? where a failing or damaged organ in the human body is removed and replaced with a new one. An organ is a Solid transplantable mass of specialized cells and tissues that work together organs: to perform a function in the body. The heart is an § Heart example of an organ. It is made up of tissues and cells § Lungs § that all work together to perform the function of Liver § Pancreas pumping blood through the human body. § Intestines Any part of the body that performs a specialized function is an organ. Therefore eyes are organs because Other organs: their specialized function is to see, skin is an organ § Eyes, ear & nose because its function is to protect and regulate the body, § Skin § Bladder and the liver is an organ that functions to remove waste § Nerves from the blood. -

Organ Donation Good Practice Guidelines

Good Practice Guidelines in the process of Organ Donation Good Practice Guidelines in the process of Organ Donation National Transplant Organization , 2011 GOOD PRACTICE GUIDELINES IN THE PROCESS OF ORGAN DONATION That “Spain is the leader in organ donations” has become a national and international slogan. It is quite clear that our system has given ample proof of effectiveness and soundness and that our donation and transplantation activity has become a reference worldwide and is motive of pride for our professionals and our society. Furthermore, our system is also characterized by its continuous evaluation and improvement. Our donation and transplantation activity, although growing in absolute terms, has remained stabilized in relative terms over the last decade. A significant number of patients are faced with long periods on the waiting list and, depending on the organ, 6 to 8% of these patients on the list die before receiving a transplant. We are also experiencing times of fortunate epidemiological changes and changes in how society treats and confronts the end of life, changes that give rise to doubts on the stability over time of our potential for donation after brain death. It was within this context that the initiative of the present project was born: Benchmarking applied to organ donation, specifically, to donation after brain death. ‘Benchmarking’ is a modern word used to refer to a practice that is as old as the human being: innately, we establish and try to learn from those who do it the best. The project has tried to identify those differentiating factors that justify some excellence results in the brain death donation process by our coordination team. -

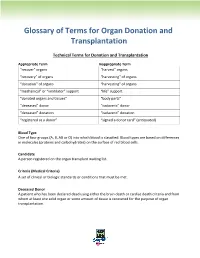

Glossary of Terms for Organ Donation and Transplantation

Glossary of Terms for Organ Donation and Transplantation Technical Terms for Donation and Transplantation Appropriate Term Inappropriate Term “recover” organs “harvest” organs “recovery” of organs “harvesting” of organs “donation” of organs “harvesting” of organs “mechanical” or “ventilator” support “life” support “donated organs and tissues” “body parts” “deceased” donor “cadaveric” donor “deceased” donation “cadaveric” donation “registered as a donor” “signed a donor card” (antiquated) Blood Type One of four groups (A, B, AB or O) into which blood is classified. Blood types are based on differences in molecules (proteins and carbohydrates) on the surface of red blood cells. Candidate A person registered on the organ transplant waiting list. Criteria (Medical Criteria) A set of clinical or biologic standards or conditions that must be met. Deceased Donor A patient who has been declared dead using either the brain death or cardiac death criteria and from whom at least one solid organ or some amount of tissue is recovered for the purpose of organ transplantation. Donor A deceased donor from whom at least one organ or some amount of tissue is recovered for the purpose of transplantation. A living donor is one who donates an organ or segment of an organ (such as a kidney or portion of their liver) for the intent of transplantation. Living Donation Situation in which a living person gives an organ or a portion of an organ for use in a transplant. A kidney, portion of a liver, lung or intestine may be donated. Living Donor A living person who donates an organ for transplantation, such as a kidney or a segment of the lung, liver or intestine.