Malta's Water Scarcity Challenges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

CALIFORNIA AQUEDUCT SUBSIDENCE STUDY San Luis Field Division San Joaquin Field Division

State of California California Natural Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES Division of Engineering CALIFORNIA AQUEDUCT SUBSIDENCE STUDY San Luis Field Division San Joaquin Field Division June 2017 State of California California Natural Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES Division of Engineering CALIFORNIA AQUEDUCT SUBSIDENCE STUDY Jeanne M. Kuttel ......................................................................................... Division Chief Joseph W. Royer .......................... Chief, Geotechnical and Engineering Services Branch Tru Van Nguyen ............................... Supervising Engineer, General Engineering Section G. Robert Barry .................. Supervising Engineering Geologist, Project Geology Section by James Lopes ................................................................................ Senior Engineer, W.R. John M. Curless .................................................................. Senior Engineering Geologist Anna Gutierrez .......................................................................................... Engineer, W.R. Ganesh Pandey .................................................................... Supervising Engineer, W.R. assisted by Bradley von Dessonneck ................................................................ Engineering Geologist Steven Friesen ...................................................................... Engineer, Water Resources Dan Mardock .............................................................................. Chief, Geodetic -

The Fairly Hydrated Knight

THE FAIRLY GAMES BOOKLET HYDRATED Play & Learn KNIGHT When building a fort, the engineers would try to enclose a natural Water in forts spring inside its walls. Often this was not possible, so they had to make other waterworks, such as large cisterns (gwiebi), smaller close-bottom wells (bjar) or a groundwater well (spiera). In some cases they brought water from afar with an aqueduct (akwedott) or an underground tunnel (mina). Draining the sewage and storm water outside the fort was equally important in order to avoid contamination and diseases. When under siege, what was the most important thing for any fort to have? High strong walls? Surrounding ditches? Weapons and gunpowder? A lot of guards? Guess again … No fort, no matter how strongly built and well armed, could survive any siege if it lacked access to fresh water! 2 3 Inside a close-bottom cistern (gibjun, bir) Fill in the missing words: bell, clean, cool, dust, evaporation, gravity, inclined, lid, locked, rainfalls, summer, terraces. 1. The rain is collected from the nearby _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _. All collection surfaces must be kept _ _ _ _ _. 2. The feeding gutter is slightly _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _, so water moves only with the power of _ _ _ _ _ _ _. 3. The _ _ _ _ shape gives stability and strength to the cistern. 4. The _ _ _ is closed when the cistern is not in use and sometimes _ _ _ _ _ _ to prevent water theft. -

Simulation of Flows and Water Quality in the California Aqueduct Using DSM2

Simulation of Flows and Water Quality in the California Aqueduct Using DSM2 Siqing Liu, Bob Suits DWR, Bay Delta Office, Modeling Support Branch 2011 CWEMF Annual Meeting, February 28 –March 2 1 Topics • Project objectives • Aqueduct System modeled • Assumptions / issues with modeling • Model results –Flows / Storage, EC, Bromide 2 Objectives Simulate Aqueduct hydraulics and water quality • 1990 – 2010 period • DSM2 Aqueduct version calibrated by CH2Mhill Achieve 1st step in enabling forecasting Physical System Canals simulated • South Bay Aqueduct (42 miles) • California Aqueduct (444 miles) • East Branch to Silverwood Lake • West Branch to Pyramid Lake (40 miles) • Delta‐Mendota Canal (117 miles) 4 Physical System, cont Pumping Plants Banks Pumping Plant Buena Vista (Check 30) Jones Pumping Plant Teerink (Check 35) South Bay Chrisman (Check 36) O’Neill Pumping-Generating Edmonston (Check 40) Gianelli Pumping-Generating Alamo (Check 42) Dos Amigos (Check 13) Oso (West Branch) Las Perillas (Costal branch) Pearblossom (Check 58) 5 Physical System, cont Check structures and gates • Pools separated by check structures throughout the aqueduct system (SWP: 66, DMC: 21 ) • Gates at check structures regulate flow rates and water surface elevation 6 Physical System, cont Turnout and diversion structures • Water delivered to agricultural and municipal contractors through diversion structures • Over 270 diversion structures on SWP • Over 200 turnouts on DMC 7 Physical System, cont Reservoirs / Lakes Represented as complete mixing of water body • -

Every Life in 19Th and Early 20Th Century Malta

MALTESE HISTORY Unit L Everyday Life and Living Standards Public Health Form 4 1 Unit L.1 – Population, Emigration and Living Standards 1. Demographic growth The population was about 100,000 in 1800, it surpassed the 250,000 mark after World War II and rose to over 300,000 by 1960. A quarter of the population lived in the harbour towns by 1921. This increase in the population caused the fast growth of harbour suburbs and the rural villages. The British were in constant need of skilled labourers for the Dockyard. From 1871 onwards, the younger generation migrated from the villages in search of employment with the Colonial Government. Employment with the British Services reached a peak in the inter-war period (1919-39) and started to decline after World War II. In the 1950s and 1960s the British started a gradual rundown of military personnel in their overseas colonies, including Malta. Before the beginning of the first rundown in 1957, the British Government still employed 27% of the Maltese work force. 2. Maltese emigration The Maltese first became attracted to emigration in the early 19th century. The first organised attempt to establish a Maltese colony of migrants in Corfu took place in 1826. Other successful colonies of Maltese migrants were established in North African and Mediterranean ports in Algiers, Tunis, Bona, Tripoli, Alexandria, Port Said, Cairo, Smyrna, Constantinople, Marseilles and Gibraltar. By 1842 there were 20,000 Maltese emigrants in Mediterranean countries (15% of the population). But most of these returned to Malta sometime or another. Emigration to Mediterranean areas declined rapidly after World War II. -

Shrinking Sea of Galilee Has Some Hoping for a Miracle 13 November 2018, by Clothilde Mraffko

Shrinking Sea of Galilee has some hoping for a miracle 13 November 2018, by Clothilde Mraffko Plans are being devised to resuscitate the freshwater body known to Israelis as the Kinneret and to some as Lake Tiberias. For Israel, the lake is vital, having long been the country's main source of water. Israeli newspaper Haaretz provides its water level daily on its back page. Its shrinking has been a source of deep concern. When two islands appeared recently due to falling water levels, it received widespread attention in the Israeli media. The Sea of Galilee has been shrinking for years, leading to the appearance of sandy spots at the water's edge It was not so long ago when swimmers at Ein Gev would lay out their towels in the grass at the edge of the Sea of Galilee. Today, they put up their parasols 100 metres (yards) further down, on a sandy beach that has appeared due to the shrinking of the iconic body of water. "Every time we come we feel an ache in our hearts," said Yael Lichi, 47, who has been visiting Believed by Christians to be where Jesus walked on the famous lake with her family for 15 years. water, the Sea of Galilee has been shrinking mainly due to overuse "The lake is a symbol in Israel. Whenever there is a drought, it is the first thing we talk about." In front of Lichi, wooden boats with Christian Since 2013 "we are below the low red line" beyond pilgrims aboard navigate the calm waters, among which "salinity rises, fish have difficulty surviving groups from across the world that visit. -

Aqueduct Architecture: Moving Water to the Masses in Ancient Rome

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2006 Volume IV: Math in the Beauty and Realization of Architecture Aqueduct Architecture: Moving Water to the Masses in Ancient Rome Curriculum Unit 06.04.04 by Ralph Russo Introduction This unit seeks to raise awareness of basic, yet, historic principles of architecture as they apply to the provision of water to an urban center. Exploration of Roman aqueducts should serve this goal. It fits the study of classical civilizations in the ninth grade world civilizations curriculum. Moreover, it lends itself to interdisciplinary teaching, a great way for students to see things in context. Studying aqueduct architecture encourages proficiency in quantitative skills, language arts, and organizational skills. Quantitative activities such as measuring, using scale, and calculating volume facilitate developing math skills. Critical reading of primary and secondary sources, document based questions, discussion, reflective writing, descriptive writing, and persuasive writing teach and/or reinforce language arts skills. Readings and activities can also touch on the levels of organization or government necessary to design, build, and maintain an aqueduct. The unit is not a prescribed set of steps but is meant to be a framework through which objectives, strategies, activities, and resources can be added or adjusted to meet student needs, address curriculum goals, and help students to make connections between the past and contemporary issues. The inhabitants of Rome satisfied their need for water first from the Tiber River. Rome grew from a small farming community along the Tiber into the capitol city of an empire with almost one million inhabitants. -

February 7, 2021 Jordan $4,965

Bethlehem Sea of Galilee Nazareth HOLY LAND HERITAGE & Jordan Jerusalem January 25 – February 7, 2021 Jordan $4,965. *DOUBLE OCCUPANCY Single Supplement Add $680 Inclusions: R/T Air - Fargo/Bismarck - Subject to change Hotel List: Leonardo Plaza– Netanya • 4 Star Accommodations Maagan - Tiberias • Baggage Handling at Hotel Ambassador – Jerusalem • 21 Included Meals Petra Guest House – Petra • Caesarea Maritima * Plain of Jezreel Dead Sea Spa Hotel – Dead • Nazareth * Sea of Galilee Sea • Beth Saida * Capernaum * Chorazin • Jordan River * Jordan Valley • Caesarea Philippi * Golan Heights • Beth Shean * Ein Harod * Jericho • Mt. of Olives * Rachael’s Tomb For Reservations Contact: • Bethlehem * Dead Sea Scrolls JUDY’S LEISURE TOURS • Jerusalem * Bethany * Masada *Passport is required • Dung Gate * Western Wall Valid for 6 months 4906 16 STREET N • Pools of Bethesda * St. Anne’s Church beyond travel date. Fargo, ND 58102 • King David’s Tomb • Mt. Zion * Garden Tomb 701/232-3441 or • Jordan * Petra * Seir Mountains • Royal Tombs * Historical King’s Highway 800/598-0851 • Madaba * Mt Nebo • Baptismal Site “Bethany beyond the Jordan” Insurance $382. Purchase at time of Deposit Day 1 & 2: We will depart the United States for overnight travel to Israel. After clearing customs, we will be met by our guide who will take us on a scenic drive through Jaffa, the oldest port in the world. Jonah set sail for Tarshish from Jaffa but was swallowed by a large fish. Jaffa was also the home of Tabitha, who was raised from the dead by Peter. Peter had his vision here while lodging in the home of Simon the Tanner. -

The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome

THE AQUEDUCTS OF ANCIENT ROME by EVAN JAMES DEMBSKEY Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject ANCIENT HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR. M.E.A. DE MARRE CO-SUPERVISOR: DR. R. EVANS February 2009 2 Student Number 3116 522 2 I declare that The Aqueducts of Ancient Rome is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. .......................... SIGNATURE (MR E J DEMBSKEY) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to: My supervisors, Dr. M. De Marre and Dr. R. Evans for their positive attitudes and guidance. My parents and Angeline, for their support. I'd like to dedicate this study to my mother, Alicia Dembskey. Contents LIST OF FIGURES . v LIST OF TABLES . vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.2 Objectives . 6 1.3 Conclusion . 7 2 METHODOLOGY 11 2.1 Introduction . 11 2.2 Conclusion . 16 3 SOURCES 19 3.1 Introduction . 19 3.2 Literary evidence . 20 3.3 Archaeological evidence . 29 3.4 Numismatic evidence . 30 3.5 Epigraphic evidence . 32 3.6 Conclusion . 37 4 TOOLS, SKILLS AND CONSTRUCTION 39 4.1 Introduction . 39 4.2 Levels . 39 4.3 Lifting apparatus . 43 4.4 Construction . 46 4.5 Cost . 51 i 4.6 Labour . 54 4.7 Locating the source . 55 4.8 Surveying the course . 56 4.9 Construction materials . 58 4.10 Tunnels . 66 4.11 Measuring capacity . -

Verification of Vulnerable Zones Identified Under the Nitrate Directive \ and Sensitive Areas Identified Under the Urban Waste W

FINAL REPORT European Commission Directorate General XI Verification of Vulnerable Zones Identified Under the Nitrate Directive and Sensitive Areas Identified Under the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive United Kingdom March 1999 Environmental Resources Management 8 Cavendish Square, London W1M 0ER Telephone 0171 465 7200 Facsimile 0171 465 7272 Email [email protected] http://www.ermuk.com FINAL REPORT European Commission Directorate General XI Verification of Vulnerable Zones Identified Under the Nitrate Directive and Sensitive Areas Identified Under the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive United Kingdom March 1999 Reference 5004 For and on behalf of Environmental Resources Management Approved by: __________________________ Signed: ________________________________ Position: _______________________________ Date: __________________________________ This report has been prepared by Environmental Resources Management the trading name of Environmental Resources Management Limited, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own -

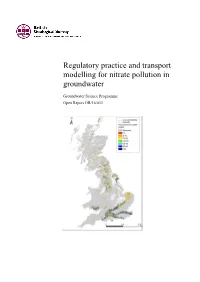

Regulatory Practice and Transport Modelling for Nitrate Pollution in Groundwater

Regulatory practice and transport modelling for nitrate pollution in groundwater Groundwater Science Programme Open Report OR/16/033 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GROUNDWATER SCIENCE PROGRAMME OPEN REPORT OR/16/033 Regulatory practice and transport modelling for nitrate pollution in groundwater M E Stuart, R S Ward, M Ascott, A J Hart1 The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2012. Ordnance Survey Licence 1 Environment Agency No. 100021290. Keywords Nitrate Vulnerable Zones; groundwater; unsaturated zone. Front cover Modelled nitrate arrival time at the water table Bibliographical reference STUART, M E, WARD, R S, ASCOTT, M, HART A J. 2016. Regulatory practice and transport modelling for nitrate pollution in groundwater. British Geological Survey Open Report, OR/16/033. 74pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. © NERC 2016. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2016 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS shops at British Geological Survey offices Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com BGS Central Enquiries Desk Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including maps, for consultation. -

Nitrate Vulnerable Zones Revision in Poland—Assessment of Environmental Impact and Land Use Conflicts

sustainability Article Nitrate Vulnerable Zones Revision in Poland—Assessment of Environmental Impact and Land Use Conflicts Ewa Szali ´nska 1,* , Paulina Orli ´nska-Wo´zniak 2 and Paweł Wilk 2 1 Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection, AGH University of Science and Technology, Krakow 30-059, Poland 2 Section of Modeling Surface Water Quality, Institute of Meteorology and Water Management, 01-673 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (P.O.-W.); [email protected] (P.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-12-627-4950 Received: 1 August 2018; Accepted: 10 September 2018; Published: 14 September 2018 Abstract: Despite concerted efforts through the European territory, the problems of nitrogen pollution released from agricultural sources have not been resolved yet. Therefore, infringement cases are still open against a few Member States, including Poland, based on fulfilment problems of commitments regarding the Nitrate Directive. As a result of the litigation process, Poland has completely changed its approach to nitrate vulnerable zones. Instead of just selected areas, the measured actions will be implemented throughout the whole Polish territory. Additionally, further restrictions concerning the fertilizer use calendar will be introduced in areas indicated as extremely cold or hot, based on the average temperature distribution (poles of cold, and heat). Such a change will be of key importance to farmers, whose protests are already audible throughout the country, and can be expected to intensify. To assess the impact of the introduced modifications a modelling approach has been adopted. The use of the Macromodel DNS/SWAT allowed for the development of baseline and variant scenarios incorporating details of stipulated changes in the fertilizer use for a pilot catchment (Słupia River).